We start by asking a little bit about your young years, your childhood, where you’re from, and how early it was, and what was it that got you interested in pursuing a career in scientific research?

I grew up in rural India, about 50 km from Calcutta. Both my parents were high-school teachers. My father worked in Calcutta and my mother near Calcutta, so we children stayed in our rural home, where we went to school, and then we would spend the weekends at our home in Calcutta. We grew up in the city and country. But I grew up mainly in rural schools. When I went to college in Calcutta, I got to see life from both the rural perspective and the urban-Indian perspective, and that was very interesting because they are quite different. But to come back to your question, when I was in grade 11-12, my father had taken transfer to where we used to live. He was the principal – the headmaster – of our school, where I went to high school for the last two years. So, I was always under watch, but I had my adventurous moments! When I entered high school in grades 8 and 9, I got really interested in science and the career that I later chose. We had a couple of great teachers who I really liked. They were really inspirational teachers, very hands-on with students. I felt good about interacting with them, being around them, and learning from them. That sort of sparked my interest in science, and in this case, it was our biology teacher who was the catalyst. Later in grades 11 and 12, just before college, in India by the time you got out of high school, you should better have an idea about what you’re going to do in college. It’s not like you go to college and then you decide. Your undergraduate major gets decided right at the start. If you want to go to medical school, you better take the medical entrance exam or for engineering, the engineering entrance exam. Our college had an entrance exam after grade 12. We had board exams and then an entrance exam. I liked science in general, more than engineering and medicine. My whole family comes from an arts background. My father was an English teacher, my mother a geography teacher, my two sisters are teachers too, language teachers. But I liked science and I thought of all the subjects that we learned at the time – language, physics, mathematics, geography, and chemistry – I liked chemistry the most. I understood chemistry the most, better than the others, and that’s why I went into doing an Honors degree in chemistry, that’s why I chose a science degree. And then later things evolved, as you progress you grow interests in new subjects.

OK, and then you went to college in Calcutta, is that correct?

Yes, I went to college in Calcutta, it was kind of a small liberal arts college, pretty old, and well known in India. It used to be called Presidency College, now it’s called Presidency University. Arts and science subjects were the only subjects that were taught in that college.

Did you have kind of an idea of what you wanted to do with your college degree? Or when did you decide and what motivated you to pursue graduate education?

Inspiration for a lot of what I did later came from college, I would say. In our class, we were 42 students, and almost half the class, 17 of them, left the year after to go to engineering or medical college, so by the second year we were down to almost 60%, but those of us who stayed we were all very motivated toward science, I think. All of us who graduated, I can name 15 of them, are all scattered around the world doing something in science, so I guess we got motivated in college for a career in research or some kind of academic work. College, I think, had a huge influence in that sense. But it’s not just the teachers, it’s also the peer group and alumni. People who graduated before us would give you a sense of what they were doing, and that we could do that too. The environment around college had a huge influence on me, and that’s when I decided that I wanted to do research more than anything else. Probably teaching, too, I like teaching, but research first.

And where did you go post-university for your graduate study? Was it also in India?

Yeah, there were a couple of choices for us. A lot of people including me went to one of the IITs first. These are the Indian Institute of Technologies, and a bunch of them are scattered around India. They are very good technical universities, and you can find a lot of people here in the Silicon Valley who come from IIT backgrounds. I went to do a master’s degree at an IIT about 200 km away from Calcutta. But I just didn’t get with the culture and I just thought “This is not what I would like to do.” I had no qualms about the research. I just felt completely out of place with the whole culture, and I decided to go back to the University of Calcutta where I finished my master’s. I did a two-year master’s degree in physical chemistry. Then I started teaching in an undergraduate degree college, as a part-time lecturer, for almost a year. And that’s when I started preparing for my GRE’s and getting ready to do a Ph.D. Then I came to the U.S. for a graduate degree.

OK, and where did you come to in the U.S. to do your Ph.D.?

That was the University of Georgia, in Athens, Georgia.

How did you come to pick that one? They had the courses that you wanted?

I think it was a choice based on what I did before in college. My degree is in physical chemistry and I was pretty interested in quantum mechanics, spectroscopy, quantum chemistry, things like that. I had applied to a bunch of places and got into three of them. I was applying to east coast colleges, mainly. I think some things really motivated me. One was a silly reason. I figured it would be really cold to go to Pittsburgh. I grew up in 85% humidity and 35°celsius (95 deg. F) in Calcutta during summer, so that is hot and muggy. And cold Pittsburgh would probably not be a pleasant place for me (laughs). The real reason is that the faculty at the University of Georgia, both in spectroscopy and in theoretical chemistry, was and still is great. And the professor that I eventually chose to work with, is great. Not only is he a very accomplished scientist, but he is great as a human being. I had three things in mind, spectroscopy, NMR spectroscopy, or theoretical chemistry, this is what I wanted to do, all of it is physical chemistry still. And I decided that I wanted to do theoretical chemistry with Fritz Schaefer, and he was kind enough to accept me in his group. Later I realized this was really a great choice because as a person he’s very well achieved but he had a real attitude of mentoring people, and anybody who knows him knows that he likes to mentor people and help them grow. The University of Georgia and Athens is a great place too. Go Dawgs!

Well, then you got your Ph.D., and is that when you applied for postdoc positions, including at Ames?

Yeah, yeah. Towards the end of my Ph.D., when I was just graduating, I also got married. I had met my wife back in high school near Calcutta, and then she went to a college near my college. When I came to the U.S. we were in touch and then she came to Georgia to do a master’s, so she also got an advanced degree at the University of Georgia. We got married when I graduated, and I stayed for a year after my Ph.D. at the UGA for a postdoc and that’s when I thought “this is not great. I need to move to a different place and work with someone else to get a different experience”. I needed a different postdoc experience, so I started applying and I waited for about six months. The NPP is like that: you applied and then waited for the decision. And when I got the decision that I was selected as an NPP candidate fellow, about a week before that I got an offer from NIH and I was facing the decision what should I do? And then within three weeks I got another postdoc opportunity, so I was thinking about which one do I want the most, and what do I want to do? What am I trained for and what do I like to do? And that’s when I decided “OK, this is what I want to do” and I came here to do the NPP.

Did it have to do at all with NASA being the space agency? Had you thought before that your work could be applied to outer space?

Only when I was actually applying to the NPP position. Before that, although it was always cool to be looking at what NASA was doing, what research was going on, and all that, I never thought of it as a career. I don’t know why. I was interested in this kind of work and I was also interested in the NIH offer, as it was also pretty interesting, so I could’ve decided that way. When I was applying for NPP I knew what I was going to do, which solidified certain things in my mind, “this is what I want to do.” I think that sort of helped me and guided me in this direction. What I’ve noticed in my case, the things that I had to work for, work hard for, I appreciated those more. Like going to IIT. I really didn’t have to work hard to get into IIT for a master’s degree, so I really didn’t appreciate it that much. But later in life, I realized that I shouldn’t have left it like that. I should’ve finished my two-year degree and then left. But because I had really not worked that hard to get that I guess I did not appreciate it that much. But the things that I really had to work hard for, yes, I valued more.

That makes total sense and how does the work that you’ve been doing at Ames for the last 10 years or so, how is it relevant to NASA’s mission and how do you justify it to the taxpayers who pay for all of NASA?

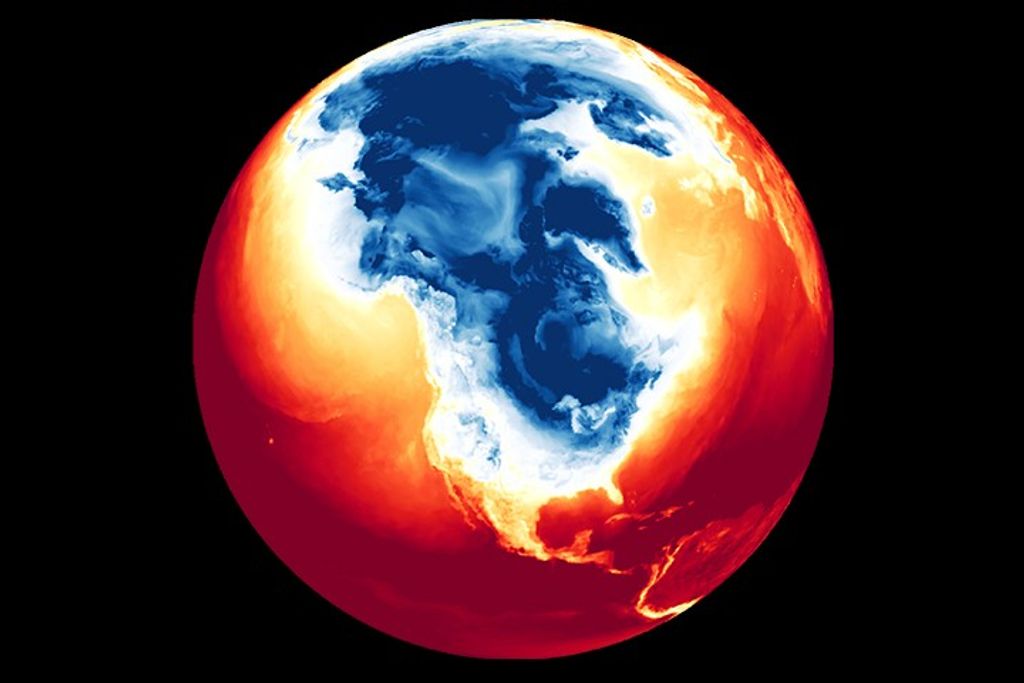

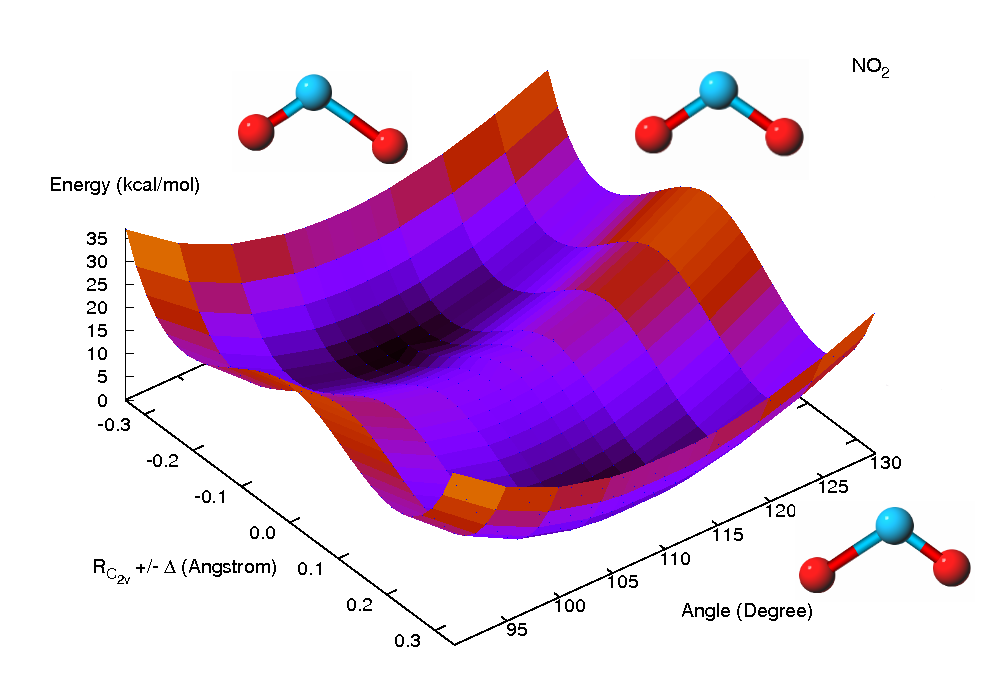

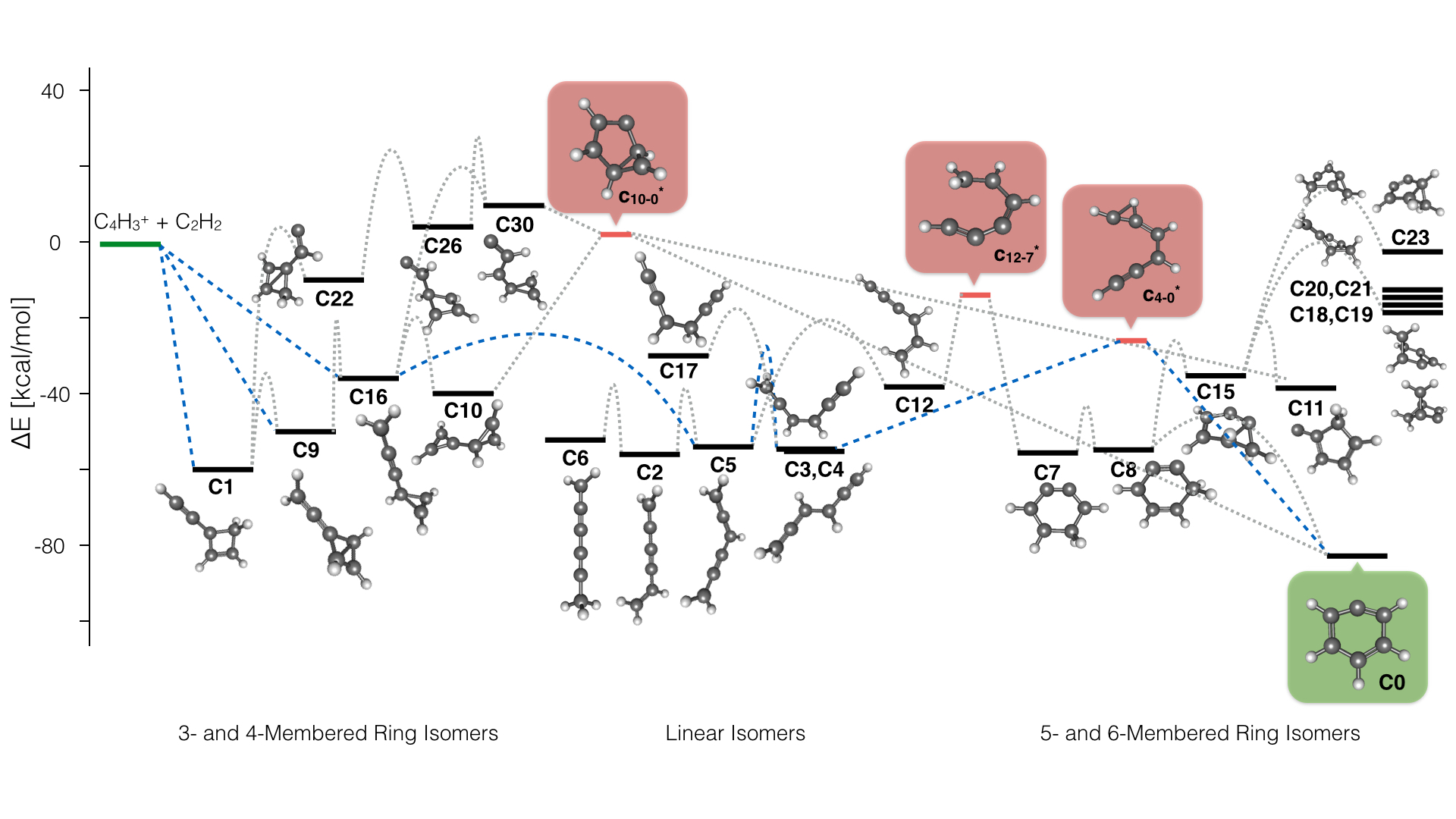

I think of the work that I do, as being a very tiny portion of all that goes on at NASA, but I see it as a long-term goal of achieving something and working towards something for the taxpayers. If you want to develop our understanding of how we came about, or how our nearby solar system works, how fundamental processes work, this may not have direct consequences as far as your health is concerned, or as far as your house is concerned, but it may have long-term implications for society as a whole. My work relates to this long-term goal, and that’s how I justify it. Now what I do in practice has two parts. When I applied for the NPP I had two goals: one was to apply my knowledge that I had gathered doing my Ph.D. in two areas: one was atmospheric chemistry and the other was astrochemistry. I pursued both for the first couple of years. My NPP was about global warming research and the first few papers that I wrote with Tim Lee, my NPP advisor, were pretty well received and well cited. I worked out how some industrial gases are extremely potent global warming agents, and I still pursue that research. It is extremely important now that we are back to doing global warming research and climate science again. The other part that I work on is astrochemistry, which is understanding how chemical processes work in our solar system, outside of our solar system, and how complex molecules originate and evolve, and how we observe them. And the final goal is basically to understand how life may have generated in other places or may have originated in our solar system. That’s the long goal.

I understand. What is a typical day like for you and these days aren’t typical, but are you able to do most of your work remotely, or are there things that you can’t do because you can’t come into the Center? Or maybe you do come in, there are a few people who are exceptions. Has the COVID thing helped with regard to your commute time? Are you able to get more done because you’re commuting less? Do you live far away or close?

I live pretty close, in Sunnyvale, so in that way no, not much of a change. Generally commuting is not a big deal. I know a lot of people commute from a long distance, but I don’t have to do that. In terms of work let me first talk about what my typical day would be if I was able to go to Ames and then I’ll talk about the COVID situation. My typical day would be spent alone if it is a perfect day! (laughs) thinking about and working on problems and writing. Now nobody can spend a day alone, you have to work with others and that’s where the interesting part comes in. The interesting part is when you talk to someone and come up with a new idea or talk to someone and realize that something you are currently thinking has been done long ago! Or you come up with an idea and you bounce it off with someone and they say, “Oh, I can do the experiment for that”. Like we did with Michel [Dr. Michel Nuevo]. Michel and I basically realized a whole line of work that he was doing experimentally, and I didn’t know and that I was doing theoretically, and he didn’t know. But we were walking to lunch at the cafeteria, and we started talking and that sort of sparked this whole 10 years of collaboration and I don’t know how many papers, maybe 15. That’s the part I like a lot. To be able to talk to other scientists, and I’ve had really, really nice chats with a lot of people, many of which actually fructified into new collaborations, new science, that I wouldn’t otherwise have pursued. COVID actually has made this all very difficult, to be able to collaborate with people. You can collaborate with your team very well because you are all sitting at home, very bored, and you have time. And if you know who to work with and if you know exactly what to do, then you can set up meetings and then go do it. I have seen scientists go to conferences and go for a walk or go to lunch or just in the hallway and come up with new ideas. This happens very organically. And because spontaneity is missing, I think a lot of new things are getting either delayed or not materialized at all. So that’s how COVID has changed matters, for me at least.

That makes total sense. Now have you ever thought that if you weren’t a research scientist what would be your dream job?

That’s funny! If I think about childhood, what would I have wanted to be, yeah? I think for a long time I wanted to be a pilot. I don’t know why, maybe I thought that was very cool, to fly a plane.

It is! I did too! I join the Air Force and thought I would learn to fly and then they found that I had color vision problems and I couldn’t qualify for flight training. But yeah, I had the same idea as a kid, that was a very glamorous job!

Isn’t it? Yeah, and I don’t know why. It wasn’t because I watched a film or anything like that. I hardly watched films in my childhood because we didn’t have a TV until I graduated from high school and my sister graduated. My father was very strict, like “No TV at home until you guys go out!” But my hope was to be a pilot but then the first time I flew on a plane, sat on a plane and went somewhere, I realized that I was terribly shocked about heights! I was really scared of heights. So being a pilot wouldn’t have worked out very well. (laughs)

I totally understand. So what advice would you give to a young student who would like to have the kind of career that you are having? Any words of wisdom for them as they come up looking for something like science research, like what you’re doing?

Sure, I think of two things I would like to tell them. One is knowing and loving what you do is very important because if you take it as a career, you’ll do it for a long time so love what you are doing. Sometimes it doesn’t happen like that but that’s OK. And the other thing I would probably tell them, and myself, it goes to them as much as to me, is to be disciplined. I think discipline in science is a virtue that is not as well appreciated but those who are disciplined go a long way and become very successful. So be disciplined in what you are trying to do.

Now here’s a question from a different angle: what do you do for fun? What are things you like to do just for fun?

Just for fun? Those are things that I think don’t involve anybody. Sometimes when I have complete freedom and if I have a lot of time on hand, I like to draw or paint. That is one of my hobbies. but this is what I like to do when I’m just sort of on my own.

Do you have a favorite image or picture or something that is meaningful to you that we might find on the wall of your office if we were ever in there, something that expresses something of your interests because it helps people to understand more about who you are in a broader sense than just what your work is?

If you walked into my office in room 107 in building 245, you’ll see there’s a long pencil drawing of Calcutta, basically the skyline of Calcutta. That’s what I call home, still, and I’ve lived now how many years in the US, 18 years? This is home for me now but everybody has a very nice memory of one place, and for me is Calcutta.

Very nice! Did you want to share anything else about your family? You said you have a daughter. Any more children?

I have one daughter. She goes to grade 1 now.

Do you play any musical instruments or have any particular books that you like to read? Or have any hobbies, talents, or sports, or anything like that?

I like sports in general, I follow a lot of different types of sports. I even played in the Ames softball league, for the Dregs. We lost all the games, we kept a clean record!

The “Dregs”? That’s like the bottom of the barrel!

Exactly! And true to our name we lost all our games, all the games that we played! (laughs)

That is funny! What accomplishment are you most proud of that is not related to your research work?

I’ve never thought about this. Accomplishment. I usually think about that in terms of my work or my career, so that’s an interesting question. I would say raising any kid is challenging.

How about the question “who or what inspires you”?

My teachers have really influenced me a lot, and my parents, too because I went to school where they taught, but teachers in general. The teachers that I had and have in my life are very influential to me. They encouraged me a lot. Apart from that, there are historical figures, writers, and scientists, who I really admire and the work they did. Some of them are Rabindranath Tagore who is one author whose picture is on my wall in my office. He was a polymath. Werner Heisenberg is another one that comes to mind and many others. But in real life, it’s my teachers mainly and I actually dedicated my dissertation to my teachers.

What do you like best and least about your job?

Oh! What I like best is that I get to work with people who are absolutely fantastic and at their creative best because they think about things that have never been done. They think of those things as real and they make them real, that’s the part I really like. But what I don’t like, maybe all the paperwork that we do.

Yeah. Get in line and take a number for that one! (laughs). Probably everybody has said that!

OK, and as far as the quote is concerned, I just was thinking of one, because of what you just said about trying to do science to figure things out, to understand, to solve problems. Werner Heisenberg said: “What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our line of questioning.”

Just one thing: I don’t think people understand the difference between rural India and urban India. Can you speak to that a little bit more? Like when you said how different it was out in the more rural area.

Right, right, yeah. What I mean by that is that I grew up in a village, I went to school that was 6 km away from home, so I would ride a bike to school, surrounded by rice fields and small paved paths through the rice fields to the school. Most people were farmers in these villages. And then, Calcutta is a big city, 12 million people, a really big metropolis, and a historical city in the sense that it was the largest city in the British Raj when the British ruled India from London. It was the capital of India at the time, for a long time. Life in Calcutta was completely different because there you see a lot of different types of people. And someone who grew up in Calcutta had no idea what village life was. Growing up, after school sometimes I would be playing football in a muddy field, completely muddy, things like that. Looking back, it was satisfying, absolutely satisfying, to grow up as we did.

It’s wonderful to have such memories and we are glad that you were willing and able to share them, so thank you. This has been delightful!

Thank you so much for doing this, both of you, Fred and Sara, thank you for asking me. I have actually, now that I think about this, it’s actually a very nice trip down memory lane for me too.

Yes, I think it’s nice to reflect on our own stories. I find it lovely to hear and to reflect on my own choices when I hear other people talk about their own, it’s great. We appreciate you taking a few minutes to share it with us today

Thank you!

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 2.18.21

To know more about Partha Bera’s work.