What do you do as a research scientist?

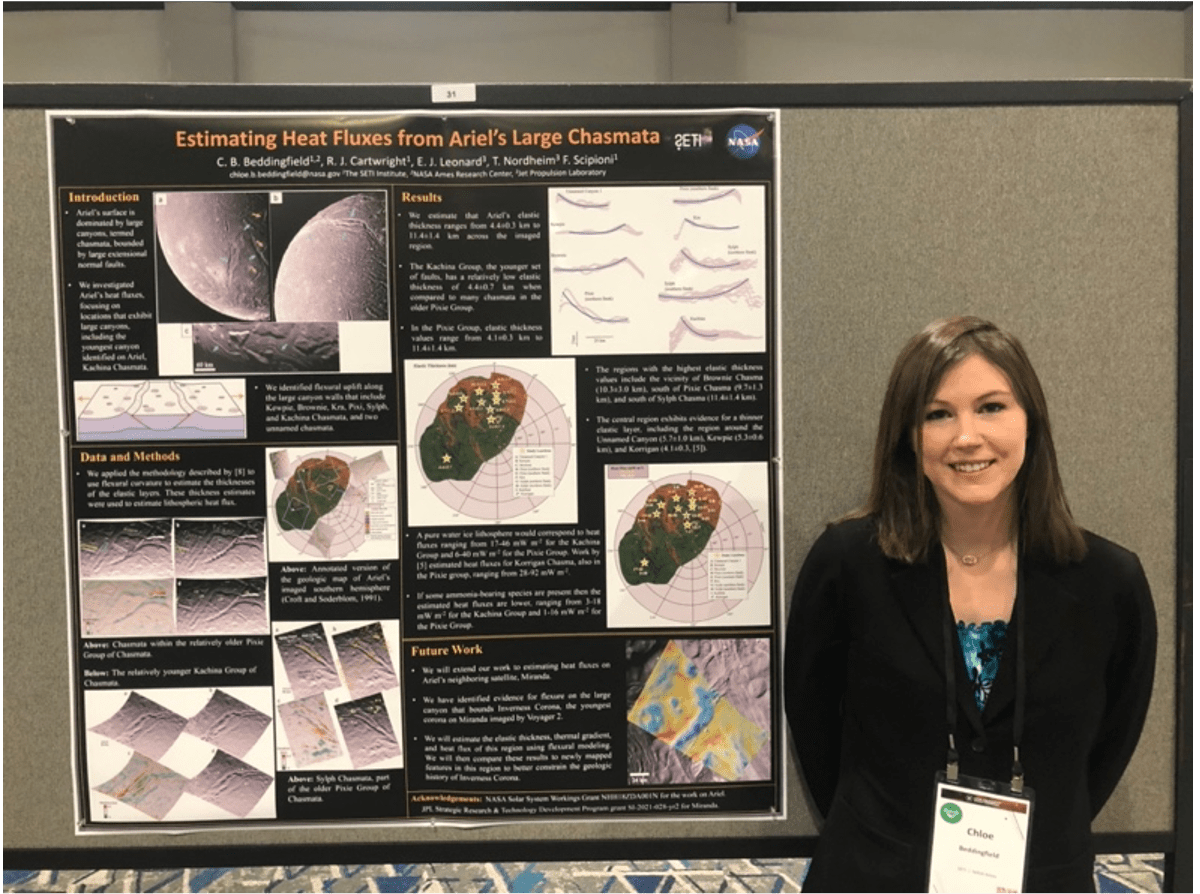

I’m in the STT (Planetary Systems) branch. I do research on the geomorphology of planetary bodies, mostly of icy satellites but also other bodies including Mercury and Mars. I also study tectonics and geodynamics. For the icy bodies I have recently been focusing on the Uranian moons. I’ve been using Voyager 2 images a lot, but I’ve recently used other images as well, including Cassini images to study icy bodies in the Saturnian system.

The bodies that I’m particularly interested in right now are the Uranian moons Miranda and Ariel. Those were imaged at the highest resolution by Voyager 2 relative to the other classical Uranian moons, so we have a bit more data on them. I recently finished up a couple of projects on Miranda and Ariel, and a similar project that will start sometime early next year will focus on the largest Uranian moon Titania. Although different icy moons have some similarities, none of them are identical and they each have distinguishing characteristics, which is fascinating.

Do you have a favorite unexpected result?

Yes. In a recent paper, I published results showing that Miranda’s regolith is over a kilometer thick in some places, which is one of the thickest regoliths in the solar system. We don’t currently know where the material came from, which is a topic for a future project. There’s an idea that perhaps Miranda was formed from material originating from Uranus’ rings in the distant past, and maybe that can also explain why the regolith is so thick. Alternatively, it could possibly indicate plume activity similar to what we see on Enceladus, or it could be ejecta from a giant impact event. Miranda’s thick regolith also has implications for its internal thermal properties as it may act as an insulating blanket, trapping heat and allowing a subsurface ocean to last longer.

You said you’ve worked on a lot of images for your research on the moons. Do you have a favorite image?

I’m going to have to say the Voyager 2 images of Miranda are my favorite right now. There’s one image in particular that shows a part of one of the coronae, which are these really bizarre, polygonal-shaped terrains on its surface. The image also shows a huge cliff called Verona Rupes, which is the one of the largest scarps in the entire solar system, up to 10 km tall.

Do you have any other favorite memories from across your career?

The most interesting, probably, was being involved with the New Horizons mission. That was the first mission that I worked on, so it was an awesome learning experience. A huge highlight was during the extended mission, when the images of Arrokoth were arriving from the spacecraft because I got to work on the images as soon as they arrived. Just being a part of that experience and working with the team was amazing.

Similarly, I was lucky enough to be a part of the OSIRIS-REx team. Working with those new images as they were being obtained to study and learn more about Bennu was fascinating. It was great to be a part of certain unexpected discoveries made during that time.

Have you always wanted to do research science?

I’ve always been interested in science in general. My parents really tried to get me interested in math and science when I was a kid, and that motivated me a lot. When I was a teenager and young adult, a lot of books that I read also got me interested in being a scientist. For example, books by Michael Crichton and others. Μy favorite book was probably “Jurassic Park”.

When I was an undergraduate, the Cassini mission was making incredible discoveries about the icy moons of Saturn, including the crazy geyser activity on Enceladus. So, during my junior year of college, I started getting into planetary science. I approached my structural geology professor at Texas Tech University, and I asked if I could do an undergraduate research project with him because I really wanted to learn how to be a researcher. So, we worked on a project on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, and I was able to present my research at multiple science conferences. He taught me about the scientific method, how to read scientific papers, how to think critically and come up with research ideas, and how to test hypotheses. He got me into research, and the more I did it, the more I was inspired and wanted to keep doing it. Once I started graduate school, I had another fantastic advisor at the University of Tennessee. She taught me a lot about how to be a good research scientist and how to think logically. So, both my undergraduate and graduate advisors were fantastic, and they really inspired me to be a researcher.

Research was what I wanted to do before I decided to go to graduate school. I loved the idea of being involved in NASA missions. Doing research in the field of planetary science is so different than terrestrial geology. You have more limited data in a way, which makes it more mysterious, and more appealing to me.

Was there a specific major that you got into for this? A specific major at your school?

My undergraduate degree was in Geosciences, and that was the most relevant for planetary science, so that’s why I chose that major. After I graduated from Texas Tech University, I went directly into the PhD program at the University of Tennessee and got my PhD in Geology.

After I got my PhD, I stayed at the University of Tennessee for a couple years as a postdoc, researching thermal inertia of impact craters on Μars. After that I saw a job advertisement for working with Ames Stereo Pipeline for all sorts of projects. The person who posted the job advertisement is friends with my advisor and one of my committee members, so there was a connection there. I had an interview with him and there was a great connection. I decided to come to Ames and that has been a great experience. He got me involved with these mission opportunities, New Horizons, OSIRIS-REx and the VIPER mission. That was something I’ve always wanted to be involved with, NASA missions.

Around two years ago, 2 1/2 years ago, there was a big move out of the offices due to Covid. Some scientists had to stay on base, but how did that all go for you?

It went fine for me. Before the pandemic I would work on site, but I would also work from home sometimes, so I felt prepared. I had all my equipment and office already set up. I had a desk and monitors and everything. Now, if there’s an in-person meeting then I’ll work on site, but I mostly just work from home. Right now, I’m focused on research which is mostly funded through NASA ROSES, and I’m also helping with some planning for the UOP (Uranus Orbiter and Probe) flagship mission.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

I love doing research. The discovery of new findings is the most enjoyable for me, where you have a question and you can test it, and then see the results come in as you collect and analyze data. Sometimes you get results that are boring, which is still useful of course. However, sometimes you get results that are interesting and then sometimes you get a completely unexpected result. Those are the best.

Do you have anything that you don’t enjoy? Perhaps the thing that you least enjoy?

Luckily, I like almost everything. However, the thing that I least enjoy is the proposal writing process. It’s great to get proposals selected, but while writing the proposal, I often want to just go ahead and do the research and not have to write the proposal. I just want to start the work instead of talking about starting the work, and then waiting to see if I can start, and of course the rejections are a bummer.

Outside of research science work and outside of working at NASA, if you could have any dream job what would it be?

If it wasn’t research science? If I could do anything, I’d be an astronaut. But if it had to be unrelated to working at NASA or science, I’d be a detective.

What advice would you give to someone who’s just starting their career in research science or just going to school thinking that this is one of the things they would like to do?

My advice would be to work hard. Just keep going and don’t give up.

Did you ever come to a point where you felt like you wanted to give up or felt that research science was too difficult?

Not really. My advisors really helped me with that. They gave me a lot of good advice and built up my confidence along the way. I guess the only point that was difficult was immediately after graduating and trying to get particular research projects funded. It’s tough because there’s a learning curve for writing proposals and you always get some rejected, especially at first. So, there’s that awkward period of time where you don’t really know how you rank until you finally get something accepted. And that can take a few years to figure out.

Would you like to share anything about your family?

I was born in North Carolina and moved around a bit, but I spent most of my childhood in Austin, Texas. My husband is also a planetary scientist, so we work together on a lot of projects. We met in graduate school, and now we write papers together, submit proposals together, and come up with new research ideas together. I also have two cats, Apollo and Nix. Apollo is obviously named after the NASA program. Nix is named after a moon of Pluto. I wanted their names to be space themed and also to sound cool.

There is a lot of focus on research in my family life. My husband and I are passionate about research and planetary science, and science in general. We definitely never run out of things to talk about. We also do other things like weekend trips and longer vacations around California and other places.

Unless there’s a proposal deadline or something similar coming up, we usually take the weekends off. We like to go on little adventures and see historical sites and state and national parks. We like video games. I don’t read novels as much as I used to, but I’m into podcasts, like the true crime genre. We also play board games with our family and friends. We’ve been playing board games with them for a long time and so we have quite the collection at our house. Whenever someone comes over, we usually end up playing something.

Interview conducted by Mark Vorobets and Fred Van Wert, October 28, 2022