We generally start with your childhood, where you’re from, and especially if there was anything in your early life that might have oriented your mind toward the career that you pursued.

Absolutely! I grew up in Massachusetts outside of the Boston area, in two different towns. Early on I was in the town of Plymouth, which is kind of famous for the Pilgrims and the Mayflower. I had an interest throughout my childhood in astronomy, and at one point I looked back and tried to figure out where that interest started. Initially, I had trouble remembering, but then it dawned on me that I knew exactly what had happened: the town of Plymouth is unique in that the middle school has a planetarium, with programs for students of all ages. When I was in first grade or so, we would take field trips there. They would turn down the lights and display the stars on the ceiling; it was gorgeous. They would also do this thing where they would show a spacecraft launch and then make a rumbling sound, so it felt like you were taking off in your seat! We went on a number of these field trips and I always looked forward to that “blast off” moment.

Wow! Like the Star Tours ride at Disneyland!

Yeah! I don’t think many young kids get exposed to that anymore, at least not in their public school systems; it’s not common. And that was just something that I got lucky on because we happened to live in that town. It was back at the time when space shuttle launches were happening. I remember being in my second-grade classroom and one day the teacher wheeled this TV in on a big cart so we could watch one of the space shuttle launches in class. It was such an exciting event, and I was thinking about what was going on in space and with the astronauts and all that. People ask me all the time if I wanted to be an astronaut and I never really did. I just liked looking at the stars, but the planetarium and shuttle launches kind of what got me started in thinking about astronomy. When I was little, at the end of every school year my parents had this little notebook they would fill out summarizing all the things I was interested in after that year and the changes, and one of the questions always was: “what do you want to be when you grow up?” I would usually pick geologist, or chemist, or astronomer… And in fact, that’s what I ended up being.

How interesting! And that is not dissimilar from other stories we’ve heard. Many of our researchers seemed to know at a very young age, what caught their interest and what they wanted to pursue, and then it unfolded for them, so that’s wonderful.

Well, I can tell you more or you can ask more questions, but I really got into astronomy when I was in middle school and high school—that’s when things kind of took off.

Well, our next question is about your educational background, especially when you were at the point of choosing majors in college and grad schools and that kind of thing.

Actually, even before that, there is more of a story. When I was ten, we moved out of Plymouth, to central Massachusetts, to another little town called Harvard. It has no relationship with the university, which really confuses tourists. By coincidence, Harvard University owned and operated Oak Ridge Observatory on the outskirts of town, mostly because it was dark there. They had a 60-inch telescope that they were using and a whole host of smaller and somewhat historical telescopes. It had some public tours but wasn’t a big place to go visit because astronomers were busy using it.

Anyhow, I was again very lucky, being in the right place at the right time as a middle school student, and later as a high school student. I got invited to participate in some summer science research programs through MIT which got me connected up with Oak Ridge. I said to the nice astronomers there, “Can you give me a project to do?” They kind of took me under their wing, and after a while, they actually gave me a key to one of the telescopes. They showed me how to operate the cameras on it and said, “Whenever your parents are willing to drive you over here you can just show up and use this equipment”. So I would go over there and take data and do science fair projects. Eventually, I graduated to the point where they asked if I wanted to do a project on the big telescope. And I got to do my first full night of observing as a senior in high school on this research grade telescope operated by Harvard University! That pretty much got me hooked.

That is an amazing and wonderful story and it kind of explains something because you came on as a post-doc about six months before I retired, so I reviewed your application, including your academic transcripts, in preparing for this interview. And I had to look carefully to even find a B; almost all your grades were A’s! You were something of a prodigy. I believe you won back-to-back “Best Research Paper by a Junior” and “Best Research Paper by a Senior” awards! That’s very impressive. So it sounds like you really got into this early and had these experiences that probably helped you going forward.

Yeah, definitely. I was reading research papers as a high school student and even started writing some at that point, so that was an important experience. And this is kind of skipping ahead a little but it caused me more recently to take on high school students and interns at NASA because there are students in the local area that are interested in astronomy. I’ll tell you a bit about them later, but I have this desire to give back. These other astronomers helped me out so much, and now I would like to pass that along. Anyway, during the summer after my junior year of high school, I got to do another amazing program called the Research Science Institute, living at MIT with about eighty U.S. and international students. And for that, I got connected up with a professor at Harvard University to do a research project. He eventually ended up becoming my undergraduate thesis advisor. So all these things happened early on, and I wound up saying “Yes, I like this field, I’m going to stay with it”.

Your academic record is so full that you didn’t even mention Cambridge and I was going to ask you about that. You spent at least a year there. Was that on a scholarship or something?

Yes! I was an undergrad at Harvard, and I was planning to go straight to graduate school, but I noticed and was encouraged to apply for various scholarships to go abroad for a year. I still wanted to do astronomy but without the grind of course work, because I knew I would have to do it again in graduate school. I won a Churchill Scholarship, which is a one-year fellowship to Churchill College at the University of Cambridge in the UK. It mainly involved research, but you have to enroll in a degree, so I wrote a thesis and obtained a master’s degree. That was really an amazing year actually because it was a totally unique experience. The culture was different, and I got into all these new activities beyond astronomy. I tried out the sport of rowing, which is really big over there. As soon as you enroll at the University of Cambridge people start talking about rowing, and whether you’re going to turn into one of “those people”. And I said, “No, no, no, I’m not going to do that, I’m not a morning person”. But before long I got pulled into the sport, and I turned into a rower! So there were lots of surprises. I ended up meeting my husband there as well.

Wonderful! You just mentioned your husband and we’ll talk about your family a little later but was he from England?

He is actually from Norway. We were both at Churchill College doing one-year degrees. He was studying computer science and we happened to be in the same college and so we met over there and then, later on, I “imported” him to the United States!

Otherwise, we might be doing this interview with you in Norway! (laughs)

Well, I have Norwegian ancestry, so it’s kind of cool. We have these old records of my Norwegian great-grandmother, and I’ve learned to speak the language, not completely fluently but it’s kind of nice having connections on both sides.

Oh darn, you disappointed me because I thought with your name you might be related to Buffalo Bill (Cody)!

Oh yeah! My side of the family has Irish roots, as well as Norwegian and Portuguese. But I’m sorry I have to tell you that I have no connection to Buffalo Bill. And I guess in this day and age with the pandemic, I should also point out that I am not related to Dr. Sarah Cody either; she is the doctor whom we keep hearing from in relation to COVID-19 health orders for Santa Clara County. It is kind of fun hearing another Dr. Cody in the news though (laughs).

I have heard of her and there were a lot of people who were not happy with her pronouncements about having to continue sheltering because of the coronavirus, unhappy that she was so rigid about the lockdown.

Yes. She’s taken a lot of flak, so I say “Nope it’s not me! That’s a different doctor Cody!”

OK, so you got multiple master’s degrees and a Ph.D. and a bunch of academic experience and then at some point, and this is always an interesting question: what was the connection to NASA and Ames Research Center?

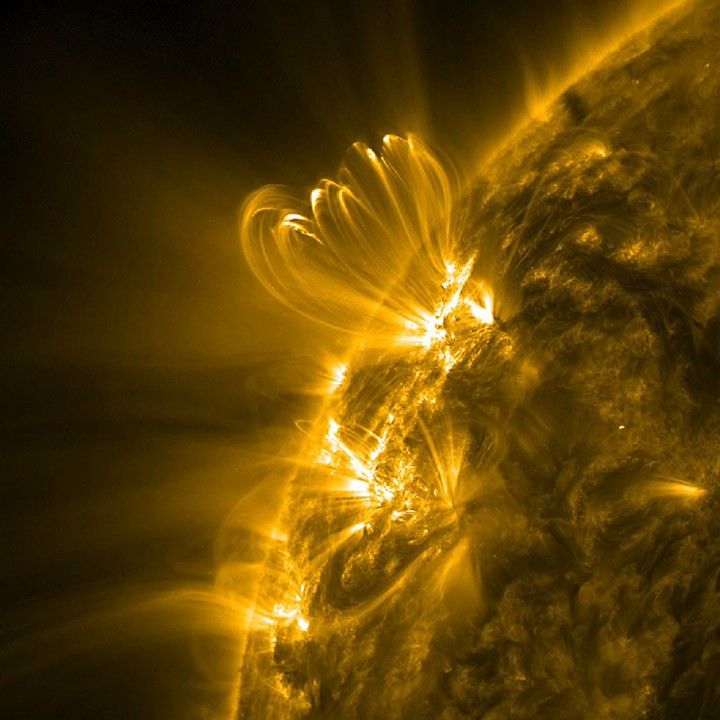

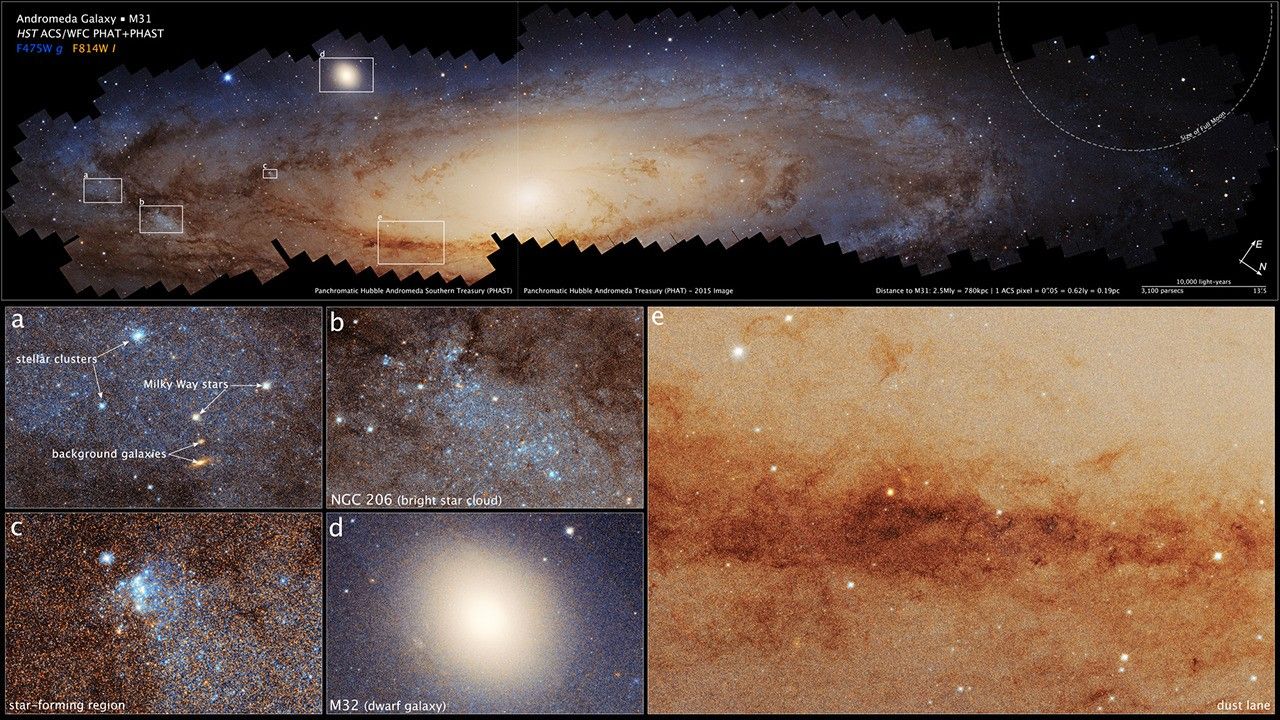

Oh yes! Well, first I guess I should say I moved to California and I thought that would be a brief visit, but I have not left! I moved in 2004 and it has been a very long stay, but a very nice one. I was in the LA area for 10 years because I did my Ph.D. at Caltech and then I also did a postdoc there. The area that I’ve been working on in astronomy makes heavy use of space telescopes. I’ve been very interested in looking at the youngest stars that may be forming planets, and in particular, looking at their wild brightness fluctuations. They are really crazy! If you look at the sun today and tomorrow, it’s pretty much the same brightness unless there’s a cloud in front of it. But if we were around one of these young stars, only a few million years old, they might be twice as bright tomorrow as they are today. I study the physical processes that contribute to those brightness fluctuations. We don’t fully understand them. I started this work during my Ph.D. using space telescopes operated by Canada and the European Space Agency and Canada. NASA’s Kepler mission had just launched, but unfortunately for me, it wasn’t very useful because it was not looking at any young stars. So I didn’t pay much attention to Kepler—at least not initially.

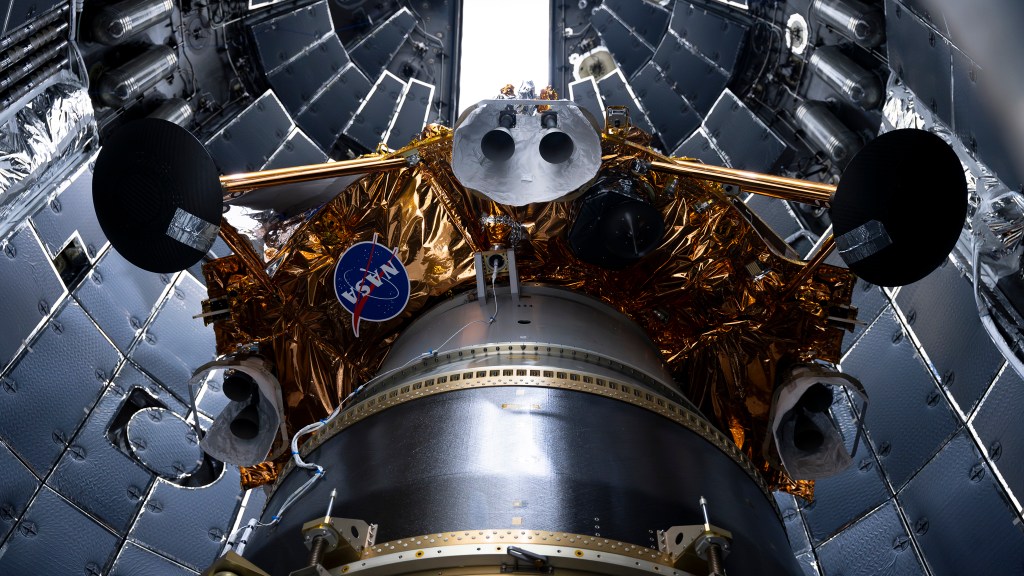

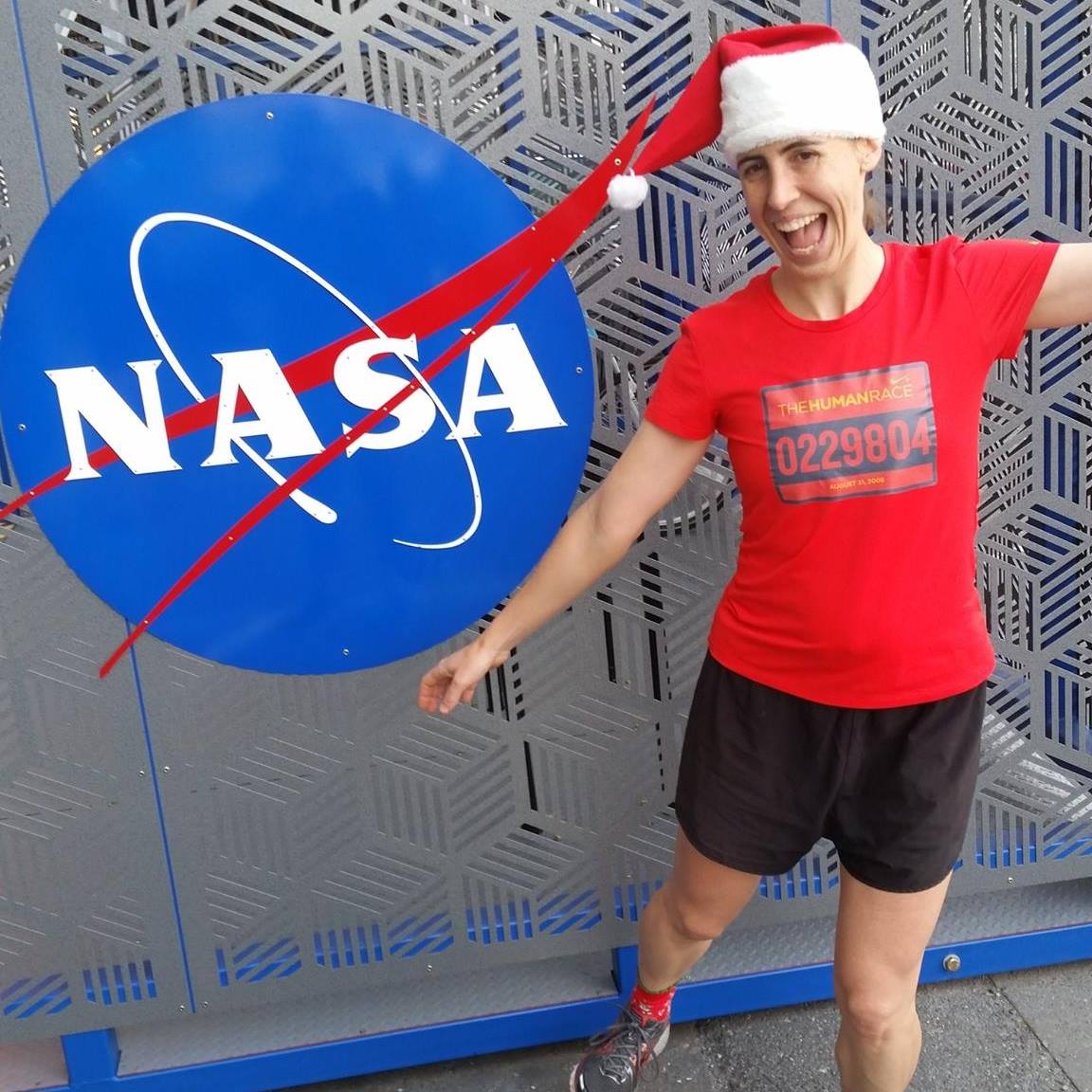

Four years into its mission, I was looking for a new postdoc job, and at the same time, Kepler had this disappointing event which was a reaction wheel failure. This failure caused it to not be able to maintain stable pointing toward the area of the sky where it had been observing for four years. Everyone thought that was the end of the NASA Kepler mission. But clever engineers at Ball Aerospace said “Wait a minute! If we look at new regions of the sky in the plane of our solar system, we can actually use the radiation pressure from the Sun’s photons to roughly balance the telescope, and keep getting observations”. And suddenly I realized, if that comes to pass, Kepler will be looking at young stars that I am interested in, which it was not doing at all before. A whole new set of possibilities opened up. Initially, it wasn’t clear whether that mission was going to continue because it would have to pass feasibility tests and receive continued funding. But I nevertheless got this idea: can I work with the Kepler mission? And a friend of mine, who had just moved to NASA Goddard suggested I consider the NASA post-doctoral program. So I looked into who was at different places, in particular Ames, and the name Steve Howell came up. I asked colleagues, “Do you know who this is?” They said, “Oh yeah, he’s a great guy, you should contact him, he’s really friendly”. So, I emailed him, and I said “Hey, I really want to work on Kepler”. Steve got back to me and he said, “Oh, that would be wonderful to have you, let’s put in an application”. And suddenly I’m thinking “Wow, maybe I’m going to work at NASA! That would be really cool!” I applied, got the position, and moved up from the LA area to the Bay Area, extending my 10-year stay in California to now over 15 years! (laughs)

That’s really wonderful! You made lemonade out of Kepler’s lemons, and that’s just terrific! I haven’t ever heard that story before.

And I’m still working on Kepler. I mean, although the mission is pretty much over now there is so much data that came out of that telescope. I’ve got another paper I need to write this summer and probably more after that; it’s just quite amazing.

You said you’re about 15 years into your career, so you are still young as I look at it. Has there been a favorite memory or perhaps a research finding of significance or perhaps an unexpected search result that is particularly memorable or that you are proud of?

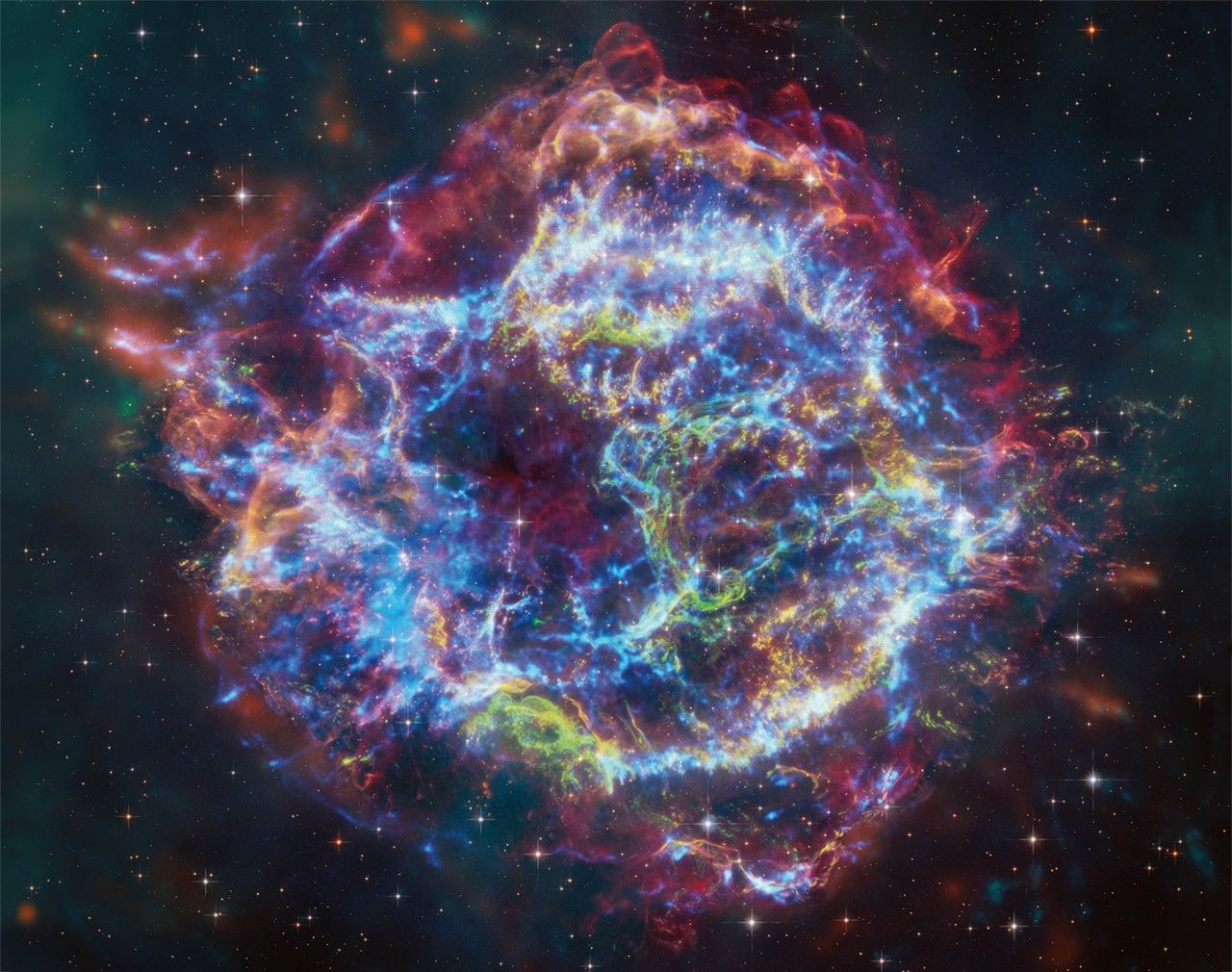

Oh! That’s a good question. I think just all of the unique things we have found that young stars are doing, thanks to our view with Kepler. What made Kepler different from ground-based telescopes is that it would stare at stars for days on end, taking data continuously, whereas if you’re using a ground-based telescope you’ve got daytime when you can’t take observations, and you’ve got bad weather, so basically the data is much more sparsely sampled. If you imagine that something interesting is happening, such as when the star has a fading event or a brightening event, you tend to miss a lot of information when viewing from the ground. So it wasn’t until we looked, first with the French telescope CoRoT, but then later with Kepler observing additional regions on the sky where these young stars are, that we saw the wide range of behavior that these objects display. I remember seeing some stars that suddenly became twice as bright for about a week before fading again. We don’t know exactly what causes that. But now we’ve got like a whole catalog of variability phenomena. Just looking at the light curves has been super exciting. We are still trying to understand it so I wouldn’t say there’s a single discovery that sticks out, but it’s more like the amazing quality of the data set that I’ve had the privilege to examine over the past few years.

Wonderful. And we often ask how your work fits into NASA’s strategic vision for its exploration and as a corollary, justifying it to the taxpayers who foot the bill for it. Now Kepler is a mission that went through all those approvals and everything so if your research is aligned with that then it’s already justified as far as NASA is concerned.

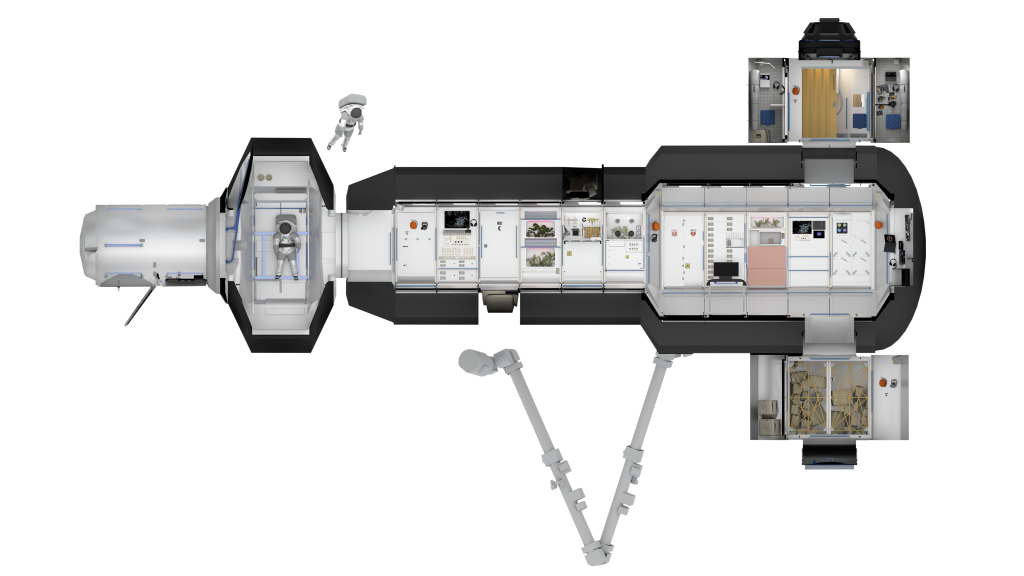

Kepler as a mission was funded to find planets around other stars and I’ve done a little bit of that, but it hasn’t been my main area. Some of my colleagues and I are extracting value from the mission and applying it to other areas that weren’t originally funded. My most recent job has been with the Kepler Guest Observer office, which in part managed research proposals coming from astronomers worldwide. Many of those proposed projects were in areas not directly related to planet finding. That is the case with my work, looking at all the crazy variability around young stars. The variability is a manifestation of both the end stages of star formation as well as the beginning of planet formation—both topics that NASA is interested in. Newborn stars (“only” a few million years old) are surrounded by gas and dust leftover from their formation, and it is the dynamics of this material that causes stellar brightness changes by either falling onto the star or obscuring its surface. Eventually, this material disperses and we are left with planetary systems. NASA has tasked astronomers with finding out how we go from the gas and dust present at a million years to the planets Kepler has found, which are billions of years old. With space telescope observations, we are mapping out the lumpiness of structure around young stars and using that to probe the formation conditions from which those planets arose.

On rare occasions, we have also discovered newborn planets themselves, but they are extremely difficult to detect among all the dust present. In 2016, my colleagues and I found the first bona fide young transiting planet found with the Kepler K2 mission. It was only about 5-10 million years old and it was young enough that it still had some of the material it was formed from, this protoplanetary disk circling around it. That was a big discovery.

So it sounds like data analysis is pretty much the way you spend your time at work, but what do you like best and least about your job?

Ah, what do I like best and least? Gosh, I’ve got to think, it’s hard because everything is so different right now that we work at home. I’m picturing myself in my office and, well, I think, let’s start with best: I have really enjoyed being around all the people on the Kepler mission. Really smart people, with really neat ideas, the collaborations were great, and I’m just so glad I made the decision to come to NASA. I’ve made so many connections with colleagues, some of whom have gone on to other NASA centers or to universities. What do I like least? Well, I don’t know, just little things right now like the fact that I have to use an ID card to log into my computer (laughs). You know, little nitpicky things like that. I’m struggling. One of the reasons I missed the previous interview was because it sometimes takes me 20 minutes to log into my NASA laptop. So it’s small things that get to me (laughs).

We understand the login part, we’ve all struggled with that. Have you ever thought if you weren’t doing what you’re doing, what your dream job would be?

Well, yes, I have thought about that more lately. It’s interesting because working at NASA, and specifically my job in the Guest Observer office, was a little unusual in that it involved both research and other duties, some of which just popped up organically. These other opportunities have shaped what I’d like to do for a dream job, so I’ll tell you a bit about them.

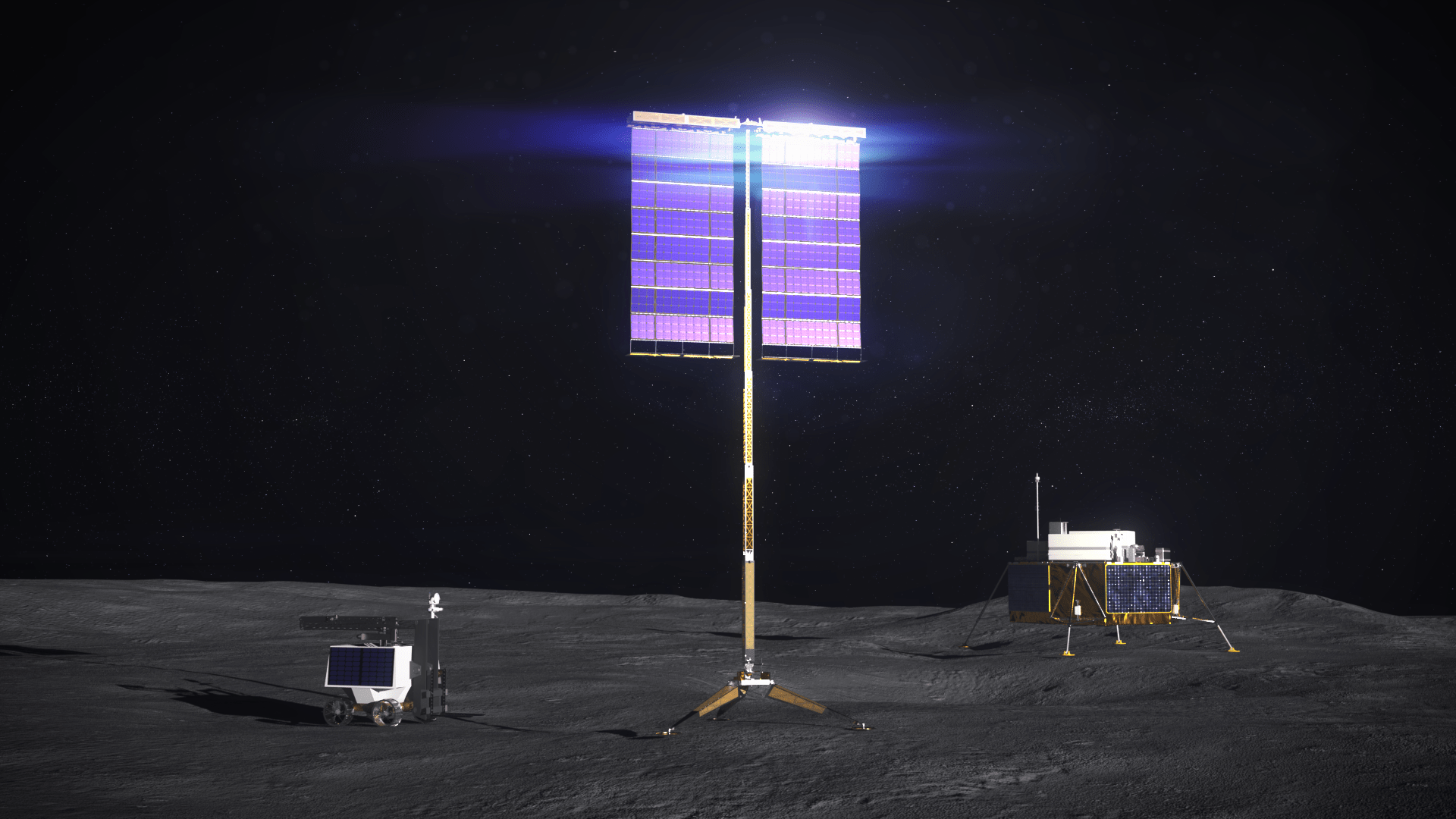

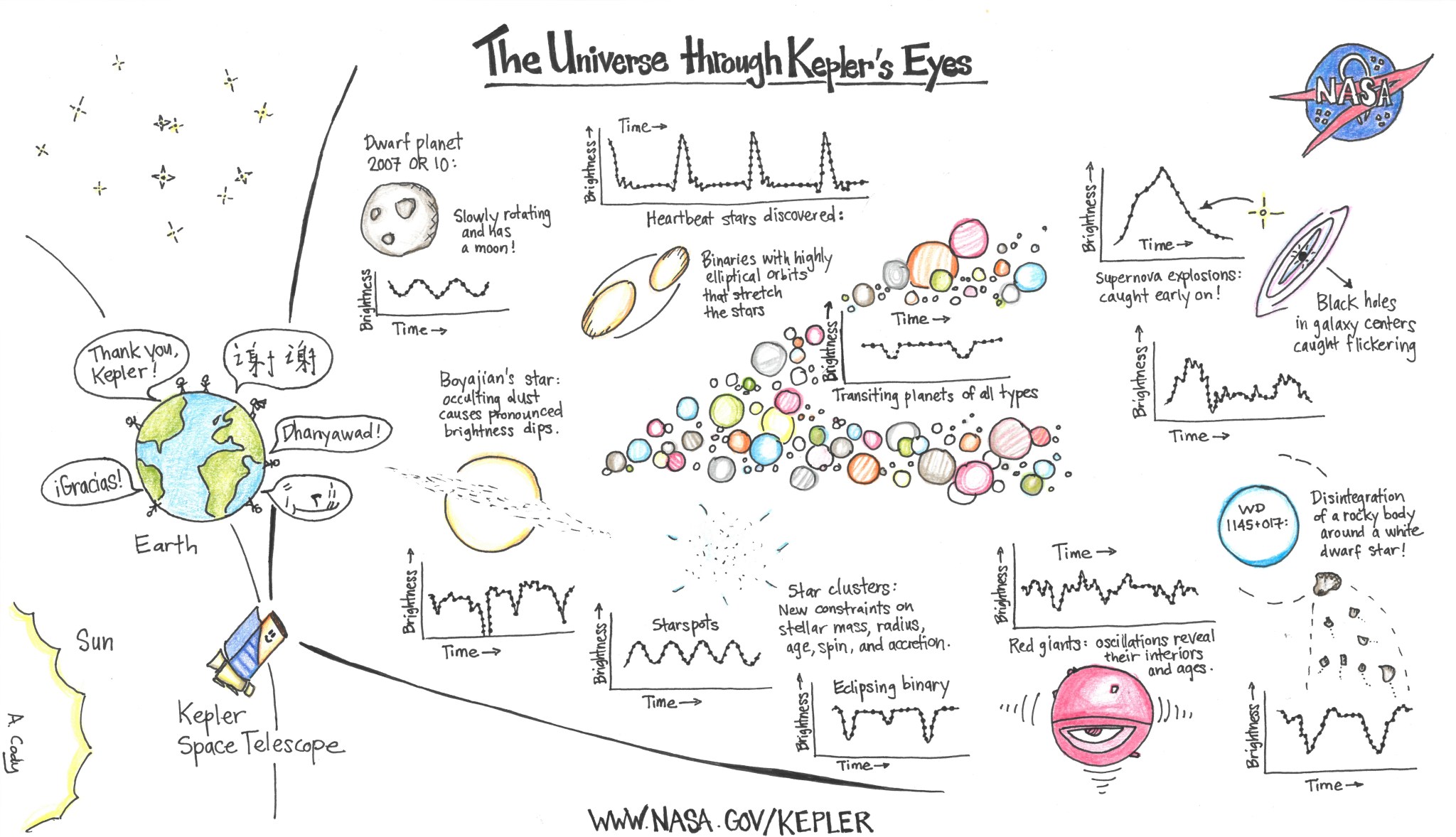

Image Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky

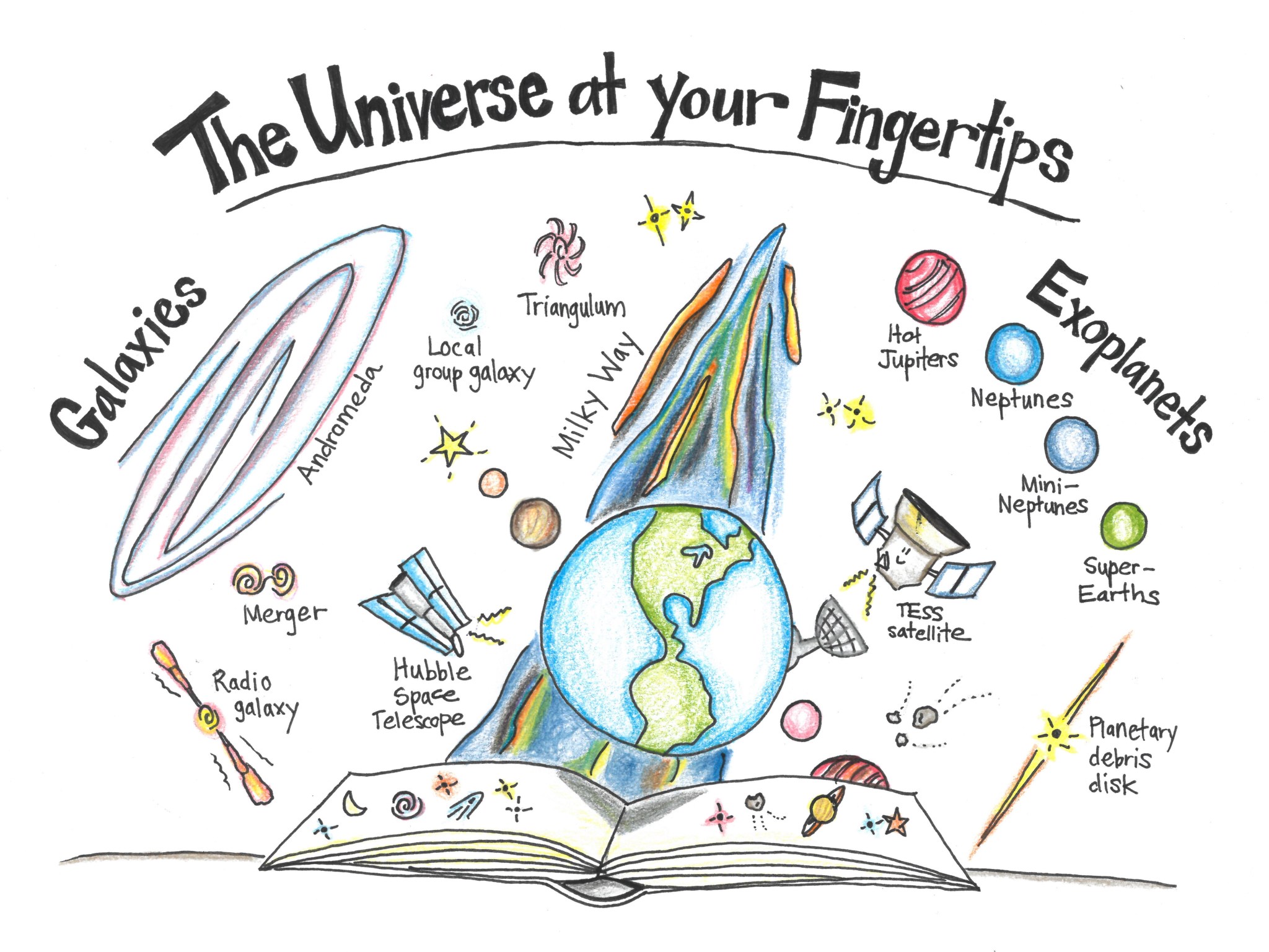

In the Guest Observer office, we not only ran astronomical proposal programs for astronomers, but we were also, to some extent, in charge of getting the science that Kepler was doing out to the community and to the public. Interesting discoveries were happening and of course, NASA has a Public Affairs staff, but it was partly on us to pick up on the science and start getting it out there. At one point, my supervisor suggested, “Every time Kepler and the K2 mission observes a new patch of sky, we ought to make an announcement with some kind of graphic showing what it is looking at now”. And he said, “Let’s put some ideas out there and then maybe we can get somebody to draw a cartoon. We’ll send it to JPL and they can have someone do up a graphic”. So one day I was sitting at home with a sick kid wondering how to occupy myself, I remembered this request and just sketched up a little cartoon, instead of sending verbal ideas or written ideas to him. And he said. “Oh, I really like this cartoon. Can you do it up for us? Maybe we don’t need to send this to JPL– we’ll just have you do it.” So I made this cartoon entitled “What is Kepler looking at now?” It showed stars and galaxies and planets, all with little labels, and we made it scientifically accurate. It was published on one of the NASA websites and upon gaining compliments, my supervisor said, “All right, the next time Kepler looks at a new field you can do it again!”. And I said, “OK, this is really fun”. I didn’t see myself as a cartoonist; it was just kind of a skill I picked up somewhere along the way. I ended up making a bunch of cartoons from the 13th campaign of K2 through the end (18th), as well as two to summarize the Kepler and K2 missions when they ended about a year and a half ago. Throughout this process, I realized that not only can I conduct astronomical research, but I can also do this other fun stuff on the side that counts toward my career activities.

I also mentioned earlier that I had picked up a few high school students along the way, people that had just contacted me out of the blue and said, “Can I do a project with you?” For a while, I was working with these two brothers, twins Shishir and Shashank Dholakia from Santa Clara. They had a science fair background themselves and did really well investigating Kepler data all on their own prior to having any NASA connections. I started advising them on projects and now they’re studying at Berkeley with an astronomy professor there. In the meantime, I’ve taken on another student, as well as had a number of undergraduate summer interns.

At any rate, I kind of picked up this interesting mixture of activities which I was really lucky to be able to do in this job, which was research, service to Kepler, cartooning, and mentoring students. While the mission is ending, I’m trying to find a way to keep doing a similar set of activities. Just this year, I’ve also taken up a little bit of community college teaching, for a basic astronomy class at a local community college. I know a lot of people that just go on to be a full-time professor and that’s one way to do it, but I feel like I have a slightly more unique set of interests that I’m potentially trying to pursue in a different way. We’ll see how it pans out. I’m currently trying to get some new projects going through applying for NASA grants.

I read about your cartooning abilities in your bio and I’m glad you brought them up and put them into this post. You mentioned having a sick kid at home and thought you might want to say a word or two about your family life, children, pets, etc.

Well, it’s a little unusual and crazy. I currently have three 3-year-olds! They are triplets!

Oh my goodness!

Yes, and I see Sara’s jaw dropping there (laughs). I had them toward the end of my postdoc time. It was a bit of a struggle, but I was working with Steve Howell and he was very understanding with all my difficulties making productive things happen during that time (laughs). So yeah, they are now 3 ½ years old, I’ve got two boys and a girl. They have different personalities and it’s quite a fun experience.

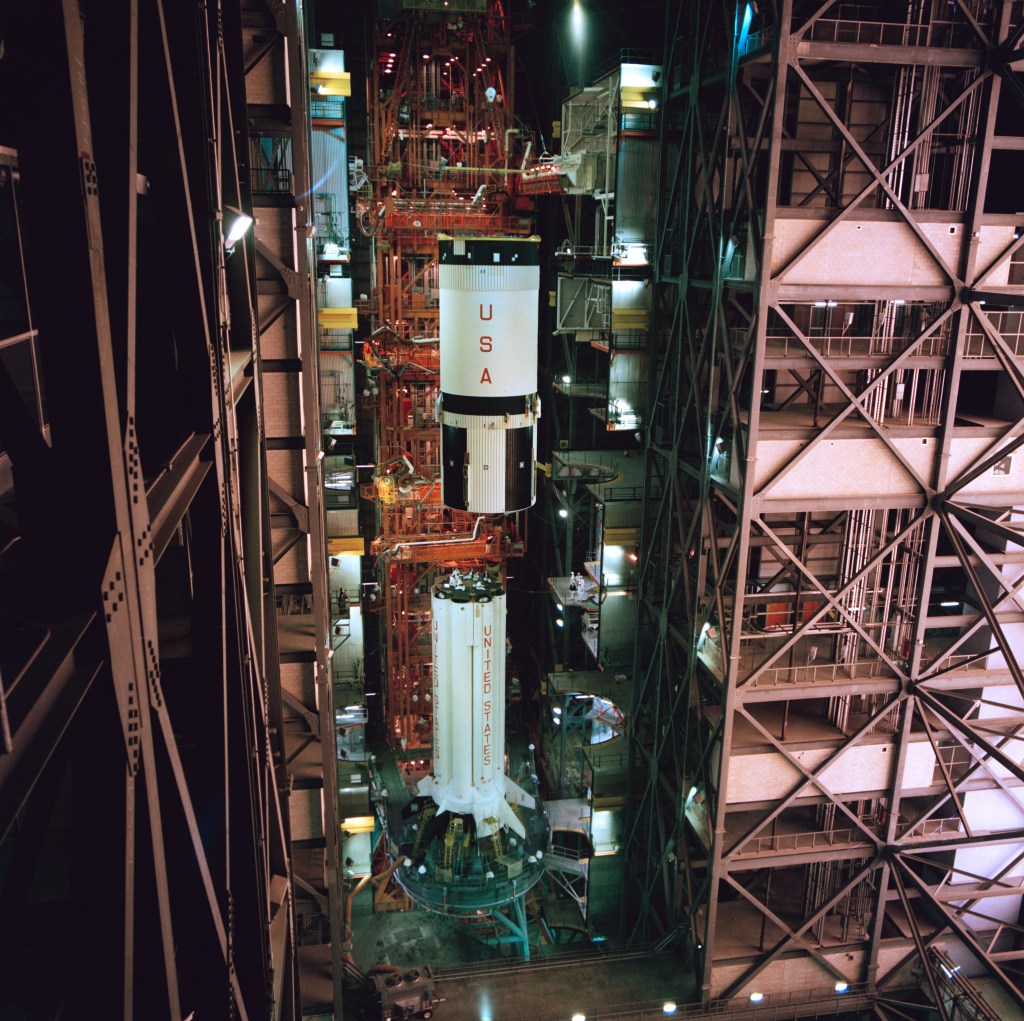

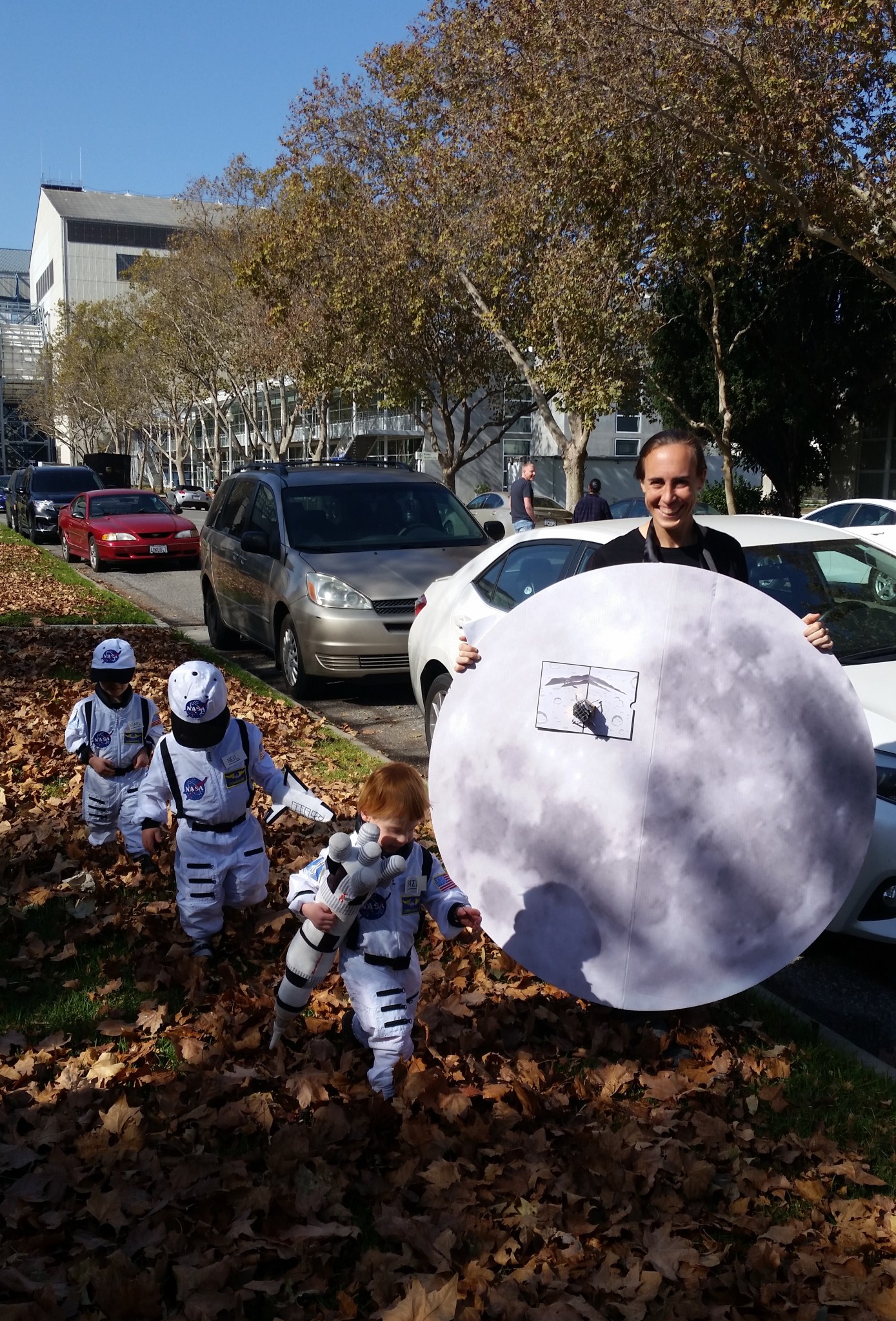

I’ll tell you a story about them visiting NASA… They first went when they were babies, for “Take your Child to Work” day, although they were completely unaware of that. But the most significant visit was last year when Ames had its annual Halloween costume contest. I had once participated, during my first year as a postdoc, wearing a silly cow costume. I didn’t win any prizes and realized that in order to do well in the NASA costume contest you’ve got to do something space related. Duh, right? So last year, I got the idea in my head that I should participate again in this costume contest and do it right this time. Initially, I told one of my colleagues, who had a six-month-old baby, that he should dress the baby up and enter the contest. My first year at Ames, somebody had done that and won the contest. My colleague looked at me and said, “No, you do it!” I said, “I’m not bringing three rambunctious toddlers to Ames!” But I started thinking, and wondering if I could come up with a theme related to the number three.

I realized we had just celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing and there were three astronauts! So I made up a giant moon placard and attached a strap to it so I could be the moon, and I ordered three astronaut costumes for the kids, as well as a Saturn V stuffed rocket. We headed over to Ames, where fortunately I had some assistance, and I also added in a stuffed earth that one of my colleagues kindly wore. We entered the costume contest and they had all the contestants go up on the stage in the Megabites cafeteria to explain what they were. I announced, “We are Apollo 11,” and then I asked the little astronauts, “Where are we going?” I handed the microphone to my daughter and she looked at everyone and she said with glee, “To the Moon!” (laughs). Well, we ended up winning the contest!

That probably won it for you!

Yes. Sometimes the kids exclaim, “Mommy we’ve been to NASA! We’ve been to NASA!” They know there are airplanes that take off on base because they saw some. We live nearby in Sunnyvale.

And whenever those big dark green airplanes fly overhead, they point and say, “Hey mom, there’s a NASA plane, there’s a NASA plane!” (laughs).

That’s a great story and our next question is what do you do for fun? With three little toddlers that’s probably quite a bit of fun and itself! But as a family are there any hobbies or things that you do as a family just for fun?

Yes, in fact. I have been become rather well known in some circles for quite a few crazy things we have done. When they were very young, both for their nap time and for my own sanity, I started running with them. I acquired a stroller that was three seats across. They are very hard to find, let me say, and they don’t fit easily on sidewalks. But I was determined to figure out how this worked. And just before I had them, I heard in the news of a triplet mom who had set a Guinness world record for running a half marathon with her kids in a similar stroller. And suddenly I had a goal, even though I had never actually run a half marathon before in my life, although I had experience running in general. I started looking into the logistics when they were about nine months old and I began running with them on the streets and on bike trails. To make a long story short, we broke the Guinness World Record in the half marathon when they were about 11 months old! It was really fun, but it was also the only way I could figure out how to get them to nap simultaneously. To this day, that remains the case. Most weekend afternoons, they go into their triple wide stroller and we go for a run. It’s getting very heavy as you can imagine. For me, it’s rather grueling, but they like the scenery and relaxation, so we keep at it. We’ve set a couple of other records along the way because I realized I was getting faster and fitter despite the weight gains. We were supposed to go for another one this April but it was canceled due to covid-19. Believe it or not, there are other people who do this and there was a really fast woman who broke the half marathon record. So we don’t have that anymore, but I’ll keep on running until the kids tell me to stop. That doesn’t seem to be anytime soon, as they are always saying, “Mommy, are we going to go running again today?” And I say “Well, I guess so.” (laughs)

How would you answer the question of who or what inspires you?

Oh, that is a good question. There are many people who inspire me depending on what area we are talking about: astronomy, athletics, or other areas. I think at the moment I look up to other moms who are able to effectively balance their family life, work, and athletics. For example, there is a woman named Roberta Groner who has three children, works full-time as a nurse, and represented the United States in the marathon this past year, coming in 6th in the world championships—at age 41!

We also ask if there are any special images or pictures of your life, your family your work, or anything that is identified with you, such as we might see on your wall or on your desk or in your office, that you would like to include with this post.

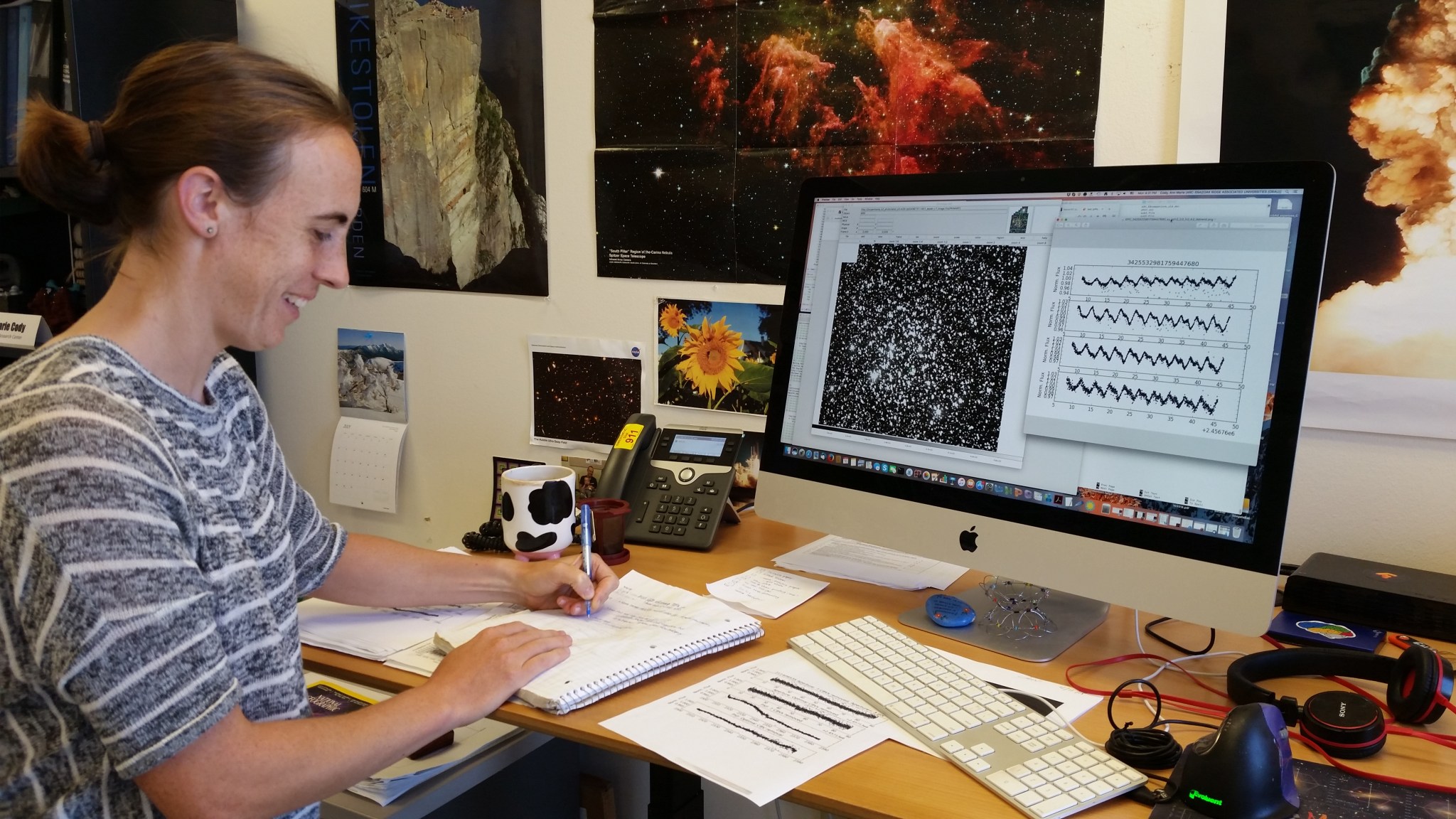

Not surprisingly, I have a lot of space photos and posters in my office. At this point, I barely remember what it looks like, but fortunately, a colleague took a photo of me working at my desk a while back, which I will include. Once the pandemic is over, I’ll be moving out of that office, from building 244 to 245 and looking forward to meeting some new faces.

I would also like to add that even though the Kepler mission is officially over, NASA has a new mission that’s taking over, called TESS. It’s not based at Ames, but it is the next thing that I’m going to be working on and am excited about it. Every time we think that the stream of space telescope data is coming to an end, something new comes along, and TESS is already providing some really exciting data. I’m going to be continuing my work, looking at young stars but from new angles. I used to look at low mass ones with Kepler, whereas now I have a couple of projects to look at the bigger, brighter ones to see how their behavior differs. It’s kind of ironic in some sense. I’ve been meaning to make a cartoon about this actually, but I’ve got three small kids who do all this kind of crazy behavior, whining, screaming, everything you can imagine. So I go off and study physics, stars, and they are doing this crazy stuff. And from what we can tell from the new data coming from TESS, it doesn’t matter the size of the star, as long as it’s a baby star, it’s doing crazy things. So that’s kind of the theme: my life and everything I study is crazy! (laughs)

That’s very aligned with one topic: youngsters! And we also ask if you have a favorite quote that is meaningful, you can provide that to us, we’d like to include that as well.

I’d like to end with a quote from Jon Kabat-Zinn, who is a world-renowned teacher of mindfulness meditation: “You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.” During whirlwinds and rough times, he reminds us to take life moment by moment just as it is.

Thank you very much for spending time with us for this interview. You have a wonderful story to tell and I think people will be interested in knowing these things about you, that they otherwise might never have known.

Thank you.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 5/28/20