Have you read some of the interviews that have been posted?

Yeah, I actually find them super fascinating because what we do as a job is unusual, to be honest, and how people get into it is just so fascinating to me. Because not everybody has that same path so it is exciting to me to see what options people chose to get where they are in life.

We are glad to hear you say that. Other people have said it is interesting and valuable and there is a lot of serendipity in people winding up where they did.

That’s my experience: luck and serendipity, with hard work!

We generally start with your childhood, where you’re from, something about your family, your parents, and if there was anything in your early years that oriented you toward science as a pursuit and potential career? How early did you feel an interest in science?

Well, I didn’t have a straight path but it is somewhat similar to other people. I grew up not far from Ames in the East Bay and never left until I went to college. I had a normal childhood, I guess, nothing too unusual. My brothers and I were very involved in sports, most of my life has been driven by sports.

Which sports? I’m curious.

All kinds of sports. I started off in soccer and played soccer all the way through high school actually, on the traveling teams, and then when I was in middle school I picked up basketball and track. When I was in high school I was a four-year varsity athlete for three different sports. I did cross-country, basketball, and track and field, and then like I said I did traveling soccer. Because school soccer was at the same time as basketball during the year, I had to choose one or the other.

That’s very impressive and it also sounds like it didn’t leave very much time to keep your grades up.

It was pretty tough to juggle, and I was not a straight-A student, by any means, but I learned very early in my life that I knew how to work at sports. I knew how you can get better at it, I knew how you had to push yourself, I knew the skills you needed to master, that came very easy for me to understand and to apply. School was not as easy to me, like how do you get better at school besides practicing? It just wasn’t as exciting to me, but I kept up decent grades. Part of it was, my Mom was very good at task management, keeping up with my two brothers and our busy schedules; she kept us on track and I like to think I learned a lot from her. We had our after-school sports and then we did homework, and it became a natural regimen. But I think part of it is I learned a lot through sports with respect to being a teammate, a leader, and strategy. I had a lot of angst and energy as a kid and it gave me a social outlet that was safe, so by the time I came home I was tired but I could focus. A joke, but also a solution for me, if I had too much energy, nervousness or excitement, or stress, my family would tell me to go run. It is still a valid solution to this day (laugh).

It sounds a little bit like you applied the scientific method to your sports, figuring out what works to make it better.

Exactly! I grew into science, I never thought about being a scientist as a kid. I didn’t think when I was young “I’m going to be a scientist”. I always, as you said, knew how to excel at sports so I just wanted to play sports, all the way through college. Again, I had science around me though, because my Dad is a scientist. I didn’t understand that as a kid because a lot of his work was classified, or he was at the office working late, or traveling for conferences. He did a lot of theoretical work, so it was all done on computers and the computers were not as fast as they are now and the graphics were not as cool. He had to sit and wait for simulations. My younger brother would tell people our Dad plays computer games for a living. Because we didn’t understand what he was doing sitting in front of a computer all day. I have a memory that on a Saturday morning, my brothers and I wanted to watch cartoons, but my Dad had just created a VHS video of the Mars crustal magnetic fields. It was just a ball of squiggly lines, and it was slowly rotating, but my Dad was so excited about it. It was really cool, cutting-edge work to him. And my brothers and I were not impressed (laughs). So, science was around me but I never really dug into science until college. In high school, I took a geology class and that piqued my interest because, well I lived in an earthquake country, and I wondered “how does that happen”? That was kind of cool. Volcanoes, too, and the oceans. I mean just that general concept of what was going on around me, of nature, was starting to interest me. But yeah, sports still held my main interest.

That’s really interesting. Did you mention brothers?

Yeah, I have two brothers and I am the middle child.

Are they all into sports like you? Or were you the only one?

Nope. We all were involved in sports. My older brother was into football and basketball. My younger brother was into basketball, football, and track.

Well at some point when you got into college you had to choose a major so how did that come about?

Again, sports drove everything for me, so when it came to picking out a college, I applied to colleges where I thought I could play sports. I was looking to play basketball or maybe run cross-country. Serendipitously, the UC Santa Cruz basketball coach came to watch a player on the opposing team to recruit. However, she was impressed by my game and recruited me to play at UCSC. I didn’t even know of UCSC but it ended up being a gem to me because, during my recruitment visit I talked to the coach, I talked to the players, I saw the campus, and it was just perfect, everything felt right to me and I said: “Yes, I want to play basketball here, and I will figure out a major” (laughs). And that high school geology class kind of stuck with me and UCSC has an earth science department so I said “OK, I’ll check this out, I’ll take a few classes” and it just started growing from there. I majored in earth science at UCSC, but they also had what they called a concentration, where you could take classes focused on a specific topic and they had one in planetary. So I took a couple of classes in general planetary science and that’s what kind of started turning the wheels for me. Doing geology on other planets! How much cooler can that be than just doing earth science here on earth? How do you do that on another planet where you can’t physically touch anything? That sounded pretty cool. So my life kind of started growing into science from there.

So was your undergraduate degree in earth science or planetary science?

Yes. It was earth science.

OK, and then you made kind of a leap, if I’m not missing something in between, to the University of Michigan?

Yes! Yes!

So tell us about that.

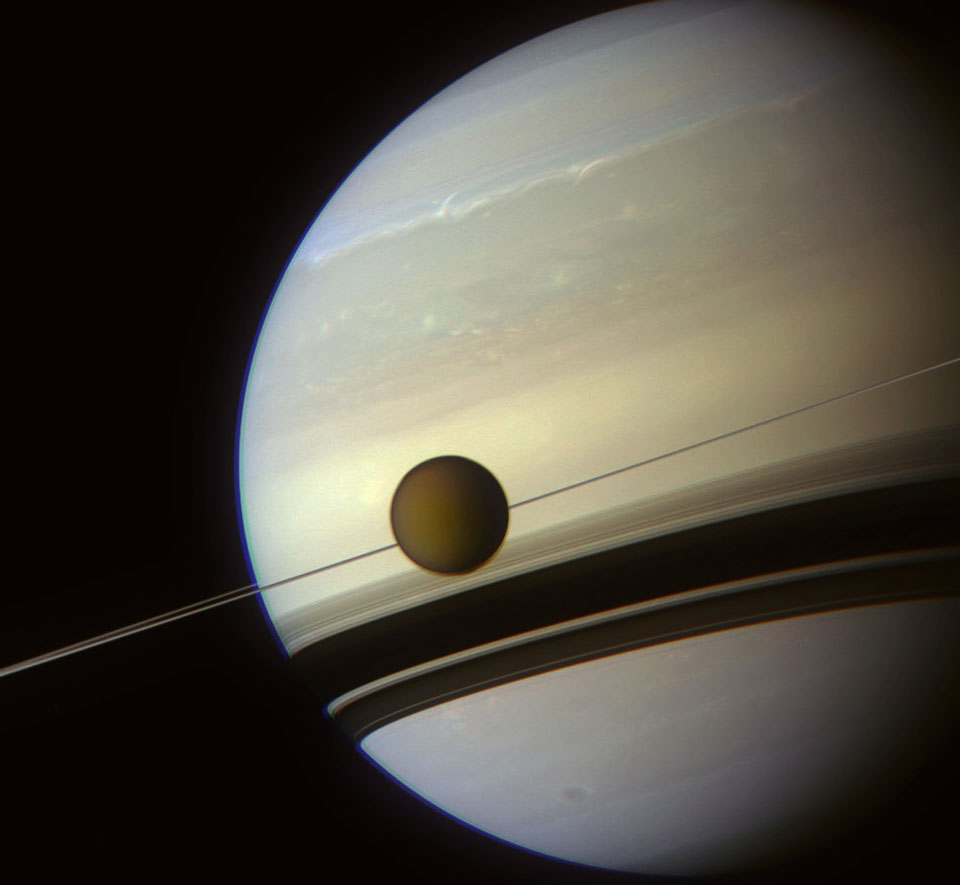

Well, I actually called my Dad because I didn’t know what to do, per se, because I was getting an earth science degree, this was around my junior year, and he mentioned getting an internship to see if I might like research, because he told me there are only two options after undergrad I either get a job or go to grad school. And I said OK. And I did an internship at UC Berkeley, and that was a different eye-opening experience because I got to work with someone on the Cassini INMS (Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer) team, and my little project was to utilize a few codes that they had and create a fly-through environment to try to predict what Cassini would measure, specifically ions. And I did that for the summer and it was pretty cool, I had to admit. It was not earth science at all, but it was so cool because these codes were like your own little laboratory. You can change parameters and see the response. I had also created cool plots and a website. So that was eye-opening, and as I was doing that I decided I would apply to grad school, and I applied to both earth science and planetary science departments. I was accepted and agreed to go to the atmospheric and space science department at the University of Michigan, which happened to be the one place I knew least about. So this is where, as you said earlier, life is serendipitous that way. You don’t know what opportunities are going to come up but you need to be open to different opportunities because from earth science to space science, there are connections, I mean physics connects them but in reality, conceptually, it’s not as connected, and I noticed that when applying for grad school. Some people weren’t as open to the idea of having a geologist do space science or atmospheric science.

So how did it go in Michigan?

In Michigan, it went pretty well. I went there to work with Cassini INMS data, but my advisor left Michigan after my first year. So I had a decision to make: either move with them or stay in Michigan and change advisors. I decided I really liked Michigan. I had already taken a year of classes, so I thought I’m just going to stay here and find another project. And that’s when I learned that Dr. Stephen Bougher had an opportunity to work on Venus. He was bringing up his Venus General Circulation Model again to compare with Venus Express observations. And I thought “Oh, that sounds cool, I want to study Venus’ atmosphere.” Again, not geology, not ions, or electrons, or anything, but a neutral dynamic atmosphere, so I worked on that, and that’s how I got my Ph.D., in atmospheric and space sciences there at Michigan. It was on Venus’s upper atmospheric dynamics. I think it went well.

It sounds like it did. And then we usually transition and try to understand how you got connected to NASA, but I already know that you came to Ames as a postdoctoral fellow. Was that directly out of Michigan and is that how you made it back? Did you apply to a number of postdoctoral fellowships and NASA is the one that you chose?

I applied to a couple. When I was leaving grad school there weren’t very many Venus postdoc opportunities in the United States since Venus Express was an ESA mission and Akatsuki, which was on its way to Venus, is a Japan mission. My husband and I wanted to stay in the States for both of our careers. I did apply to NCAR (National Center for Atmospheric Research) in Boulder, Colorado because they were talking about expanding their atmospheric modeling work to planetary, but then I heard about Bob Haberle and Jeff Hollingsworth’s work in Mars modeling, and I wanted to stick with modeling planetary atmospheres. I liked the atmospheric modeling perspective, so yes, I applied for the NPP. I’m glad I didn’t pursue Japan because Akatsuki missed their orbit insertion so I would have had limited work there for several years (laughs). So again it’s very serendipitous! Between Colorado and Ames I was going to be happy, but I preferred the idea of being back in California working on yet another planet within a group of scientists. And my husband would also be happy to get back to California and out of the snow.

Is he from California? And what does he do?

Yes, he’s from the Bay Area, too, and he’s an accountant working with non-profits.

So you came to Ames almost 10 years ago and you’ve stayed here. Can you take us through those decisions, to finish your postdoc and, well, you must have liked it here.

It was a family decision. Both of us really enjoy our jobs and we wanted it to be a place where both of us would be happy. And obviously, the Bay Area was not a hard decision for us because both of our families are here too. It’s really convenient and the Bay Area is beautiful. It’s expensive but it’s beautiful. Additionally, I really liked the environment at Ames. Again, it goes back to sports, I like working as a team. I like having people to talk with and throw ideas around with. In grad school it was just my advisor and I, and it was great, he was easy to talk to and we talked a lot, but the idea of having a team with lots of people with different experiences seemed intriguing. That’s what Ames offers and I have that opportunity to talk with the people in my Mars group, but even beyond that group. It can seem overwhelming to me, in a good way, but everybody knows someone and the skills and experiences range too. Ames provides avenues to study different planets and provides different opportunities. And I like that aspect, it is nice to have that support.

I identify with that because I came up through Ames, you mentioned that your husband is an accountant, I came up doing financial and resources management on projects and I always envied the engineers because there were dozens of engineers and they could always collaborate on a problem and go find a chalkboard and discuss everything. I was trying to balance the cost and schedule and nobody else was doing that, so I felt somewhat alone. I like the collegial aspect of Ames where you can work on things together in groups and bounce things off of people and have them look at it with a different pair of eyes, that’s a cool environment to be in.

I agree, and that’s a good perspective, very nice.

So you’re at Ames now and we’d like to know about the interesting work you are doing, what you’re currently working on, with an eye toward justifying it in terms of the agency’s strategic vision, how it fits into NASA’s plans for exploration, and to the taxpayers who basically pay for all of it. Why is it important to them?

I always find that a fun and funny question. Because it really isn’t obvious to the general public how what I do is beneficial. But it is fun to tell people how it is beneficial because I love what I do. I work on Venus’s atmosphere and on Mars’s atmosphere. And just inherently between those two, to me it’s fascinating to compare and contrast but for the person, say my next-door neighbor, why would they care, besides that, it sounds cool? I always put it in the context of Earth and the fact that we talk about climate change all the time, people worry about it now, we’ve got different weather patterns now. Earth itself is changing all the time, and we are trying to understand all the forces so we can predict those changes. The atmospheric models I use for Venus and Mars are based on Earth assumptions, and then we change parameters depending on what we know about the planet, I mean we know that obviously, Mars is smaller so we change the model because the radius needs to be smaller. Well, how important is that for understanding Earth? Or for understanding how our climate is going to change? Venus slowly rotates. What caused this and what would Earth’s climate look like if it became a slow rotator? So I love the comparative analysis of all the planets, but it all brings it home, in the sense of the way we understand Earth is how we understand the other planets, not just in our solar system, but as we learn more about exoplanets. Because everything we do in planetary is based on Earth assumptions, so we’re constantly testing our knowledge and understanding of how Earth is going to change, which impacts questions like “Should you take an umbrella or wear your snow boots?” (laughs). But it does bring it back. And then it’s also that you learn new discoveries that will change humans’ life. I mean by pushing and understanding the different technologies you can use with different planets, it will change how we can view and analyze our own planet. So I have always kept that as my big umbrella of understanding and justification for why it is not only fun but important to study planetary atmospheres and I hope that makes sense to people.

No, it makes perfect sense, and with regard to the work that you do, is it primarily such that you can do it by computer and remotely? What is a typical day like for you? Do you work mostly analyzing data on a computer or do you have any lab work associated with it? Or any observations, anything like that?

I’m primarily computer-based, so I just do numerical simulations. They’re kind of like what meteorologists use for forecasting, but I use it for Mars and Venus’s atmosphere. It’s what we call general circulation models or global climate models. Everything I do is on the computer. For the last few years, I’ve been doing a lot of numerical development. That’s really, you’re just in the code, trying to build more parts to the code to represent more physical processes and to expand the code’s application. It’s not been as science-intensive as I would like, but to me, that’s how numerical studies work. You put a ton of effort into building your tool and then you get to reap the rewards by doing a lot of science and comparisons and things like that. I feel like, with Mars especially, that’s where I’m at: I’m trying to develop this tool to really enable a lot of the science that I can do, to compare data from the many Mars missions. Venus, that code is a little more archaic but it’s developed, it’s a little bit easier to do science, but there’s more “upkeep” development that needs to go into that model. But I’m more on the Mars path right now.

It sounds like you’re operating pretty well within this pandemic constraint that we have. You probably miss the camaraderie of having your colleagues nearby but you can probably do some of that with Zoom, etc., so you’re probably less affected by the “stay at home” order than some other people.

Yes, I’m lucky in that way. Nothing has changed much, except that I use to have a pretty long commute, and now I don’t have to commute, which is nice. The tough part is that I have new interns (my kids) that need a lot of training (laughs). My kids are home most of the time, so it’s not like being in my office and just being able to focus on work. (laughs)

When things were more normal, what did you enjoy most and least about your job?

Well, the least is the easier question because there are too many things to do, and that really bugs me and drives me nuts. It is very upsetting to me because there are so many science questions I want to work on, there are so many people I want to connect with and work with that I’m physically unable to do it, . . . and mentally! (laughs) So that’s the bad part about my job, there are just too many cool things to do so it can be challenging to focus. I know people talk about the paperwork not being fun and yeah, writing proposals is a pain and I do suffer from that, except to me, writing a proposal actually helps me center myself. Again, as we were just talking about “this is a really cool science question”, but it forces me to step out and ask “What’s the reason? Why? What’s the bigger question?” It really actually helps my scientific drive, to write proposals, in a way. It’s still a frustrating process. What I like about my job is the discovery or the understanding of non-linear connections. I liked this in sports and I like it in science. The fact that if you do this, how does it impact the rest of the system? I’m really fascinated by that. I enjoy watching these developments within the codes and just the science in general. I don’t know if that directly answers your question.

Actually, it sounds like having too many science questions that you want to address could be what you like best AND least about your job!

Right! (laughs) It’s a double-edged sword, yes, exactly!

With regard to your research, so far in your middle-career or wherever you feel you are, have there been any interesting findings or discoveries that you have helped develop or discover? Or significant or interesting research findings from your work?

With Mars, I’ve been in this kind of numerical development loop. But what I am finding out about the workings of the main code is interesting. What I haven’t done yet but I’m excited to tackle is really understanding the connection between the lower atmosphere and upper atmosphere. It’s a recurring theme in understanding atmospheres because for a long time we’ve kind of ignored those connections, mostly due to not having data or computational power, so I’m on the path to wanting to understand it. And Venus, I’ve found how much the upper atmosphere dayside impacts the nightside due to Venus’ unique circulation. It was so cool to see and understand this connection. This connection is a source of an observed sporadic warm region which was puzzling due to the nightside being very cold. I apologize, there isn’t one major thing that I’ve discovered or found yet. But I feel like I’m building pieces to create a bigger accomplishment or discovery of what’s going on within these planets and that’s part of why I want to keep building these atmospheric models because there’s going to be a big breakthrough. Seeing how the full atmosphere works together, not just the lower atmosphere or the middle atmosphere, but how a missing piece or understanding in one of those regions could be the connection to understanding another region.

We can feel your energy and passion for your work but now we’re going to throw you a curveball: if you weren’t a research scientist, what would be your dream job?

You know that is a curveball, without question, because I’ve never thought about what I was ever going to be so there was no other option. But on the other hand, life would have created something. I like analyzing, although I don’t know exactly what those jobs would be. I don’t know if it would be like sports analysis or some other kind of analysis, but I like seeing connections, so something along those lines I could see creating or finding. As for now, there isn’t, I don’t think, a “dream” job because right now this one is checking all the boxes. It is just the perfect job, if there can be one, you get to have the camaraderie, you get the creativity, you get the analysis side of things, you get to discover new things, and see people discover brand new things that no one’s ever seen before. I don’t know, I don’t have a great answer! (laughs)

Sounds like you landed in the perfect place for you, that’s great. If a young student or early-career researcher came to you and said “Wow! I like what you are doing. I’d like to have a research career like that.” What advice would you give to a young aspiring student who would like to pursue or have a career like you are having?

It would be to keep your options open. I haven’t thought about this one, but it’s one of those, you need to work hard, but you also have to have enthusiasm. I know people don’t like to reach out to people they don’t know, but if you come into any conversation with an open mind and curiosity, it’s going to lead you to something. I don’t know if it’s going to lead you to what I’m doing, per se, but it’s going to lead you to something that you enjoy. I just felt like science was a good option and fun and I just kept trying to talk with people, and just followed what was curious to me, and ask people about what they are working on. Reading the interviews you’ve had with people, it’s very inspiring. You realize, “Oh, so that’s an option!” I guess it’s just to communicate and reach out to other scientists if that’s what you’re looking into. Take a lot of different classes to get a feel for what is out there because there are tons of options. We’re creating a lot of new fields that are kind of combined. Planetary science was not a widely available major when I was in college. Things are constantly changing and you can create your own thing. It’s always having a positive mind, you’ve got to be willing to work and talk to people. People can be shy with reaching out, and I get that, but you’ve got to put yourself out there a little bit, with a smile, and people will talk, it’s crazy but they won’t stop talking about what they’re passionate about.

It does, in fact, it prompts another question: you would be so perfect, the schools are closed now but you would be the perfect person for visiting the schools and inspiring the young people there, because your whole attitude and your energy are so infectious, in a positive way.

It’s funny because I’ve been interested in doing it but am not very good at it. In grad school, I was part of a Teaching Fellowship to see if I would like to teach. I learned very quickly that I liked the idea of teaching but actually what I liked was working with the kids one on one, and what inspires me, is watching people have the light bulb turn on. Watching kids, and people, be excited about something. During that Teaching Fellowship, I set up a field trip for the classes I was helping at a very underrepresented high school, where the dropout rate was 50%. I was trying to motivate and show what you can do with chemistry or astronomy. It was a field trip to the university during the graduate student conference so the high school students could see current research. I also had a meteorologist give a talk about tornado chasing. Watching the whole class seeing the videos and see the excitement and the curiosity and the questions, was really fun to see. I saw kids who never asked a question in class or barely show up for class have conversations and asking questions with the graduate students. I really enjoyed doing that and seeing those kids get a glimpse into being a scientific researcher. I haven’t really gotten into those routes yet here at Ames but I like talking to kids. My kids’ friends ask me all the time “Do you really work for NASA?” and I say “I really do!”, it is mind-blowing to them. Then they usually ask “Do you know about (some supernova event)?” and I’m like “I don’t, but …. ” and we launch into some other fun planetary topic. It is always fun. It’s something I would like to do. I haven’t done enough of it, that’s for sure.

Well, here’s a question a little bit along that line but wide open, and that is: what do you do for fun?

Well. Interesting. My thought, of course, is “working”. But besides work, I like to play with my kids. Creativity doesn’t stop at work.

How many kids do you have?

I have two. My son is eight and my daughter is five. So they are still young, and I learned once these kids were born, that you constantly have to be creative with them to keep them out of trouble (laugh). And it’s kind of fun. And it feeds back into work, like “I’ve got to wash dishes, and what do I do with a two-year-old who wants to wash dishes?” Well, you put a towel out and get a tub with water and give them some plastic cups to wash while you wash! I like being creative with my kids. It helps me work on breaking concepts down for anyone to understand. I like being outside. I like walking my dog although she’s getting old so she can’t walk far and she’s gotten slow. I like to go for runs, I just like being active. In a perfect world, I’d love to be reading more books. But that’s gotten harder with kids and with work and things. It’s hard for me to schedule time for reading. And I like hanging out and talking with people. Also, I do enjoy watching sitcoms, some drama series, and sports.

Do you have any hobbies or talents, musical instruments, things like that?

Nope. I think the only talent I’ve got is that I can still run (laughs). I can play a little basketball or a little soccer (laughs), my knees have not given out yet. Otherwise, I don’t . . . I’m not a great cook and it isn’t something I really like to do. I don’t play instruments, only a few years of the piano when I was in middle school. Can’t say I am much of an artist either unless you count drawing and art activities with the kids.

How about this question, then? What accomplish are you most proud of that isn’t science-related?

Well, there are a lot of small accomplishments that have led me to this, but honestly, I think the biggest thing is, this sounds weird, but being able to play a sport in college for four years and major in a science degree, and I say science particularly because usually, science has labs, so it’s not just the class schedules but you also have the lab schedules involved and on top of it you are squeezing in practices and travel for games, and things like that. My freshman year, our practice time was during the only time the cafeteria was open for dinner, so I had to be creative since there weren’t any other food options at the time. I kept a decent schedule and I kept up decent grades. It sounds weird too, but Division 3 level athletes are not well supported (i.e. tutors, scheduling, training facilities). I had to figure it out on my own and work with the counselor on how to get classes when I could and be able to fit in practices and training time and study time. Sometimes I had to take classes ahead of schedule to make sure I would graduate on time. I consider that a pretty big accomplishment, just learning how to balance a lot of things on my own.

I certainly agree, speaking as someone who went out for baseball in high school and didn’t make the team and never got a letter for a sweater, I think it’s very impressive to do all of that you did in sports and keep your academics up, and your science and everything, so hats off to you for that. One of our last questions is who or what inspires you?

Well, I’m sure you probably already know this: it’s people. People inspire me. People who have clarity in their goals, whether they’re scientific, athletic, or academic, whatever that goal is, that have clarity in that and commit to it, and just watching or hearing about them working through it and achieve it. To me, that is very inspiring. And that goal can be at any level. My husband was doing a “steps” competition with his co-workers and I kind of laughed because a goal to him is to have a certain amount of steps a day, which is a great goal for him but to other people, such as marathon runners, I’m not a marathon runner, it sounds like a small minuscule goal. To me what’s inspiring is that he set that goal, he worked at it, of course, everything is connected to sports for me (laughs), and it’s the same thing with science, you’ve got people who have these questions, and they stick with it and they work at it and, every publication, it’s just, looks at what they were able to achieve when they committed to this. To me, I don’t know why, but reading these interviews, it’s like “wow!” that is so cool, you are able to hurdle this and get to here and get to that point, it’s all inspiring to me in that way. So yes, seeing that curiosity, and love, and passion, turn into something is very inspiring to me.

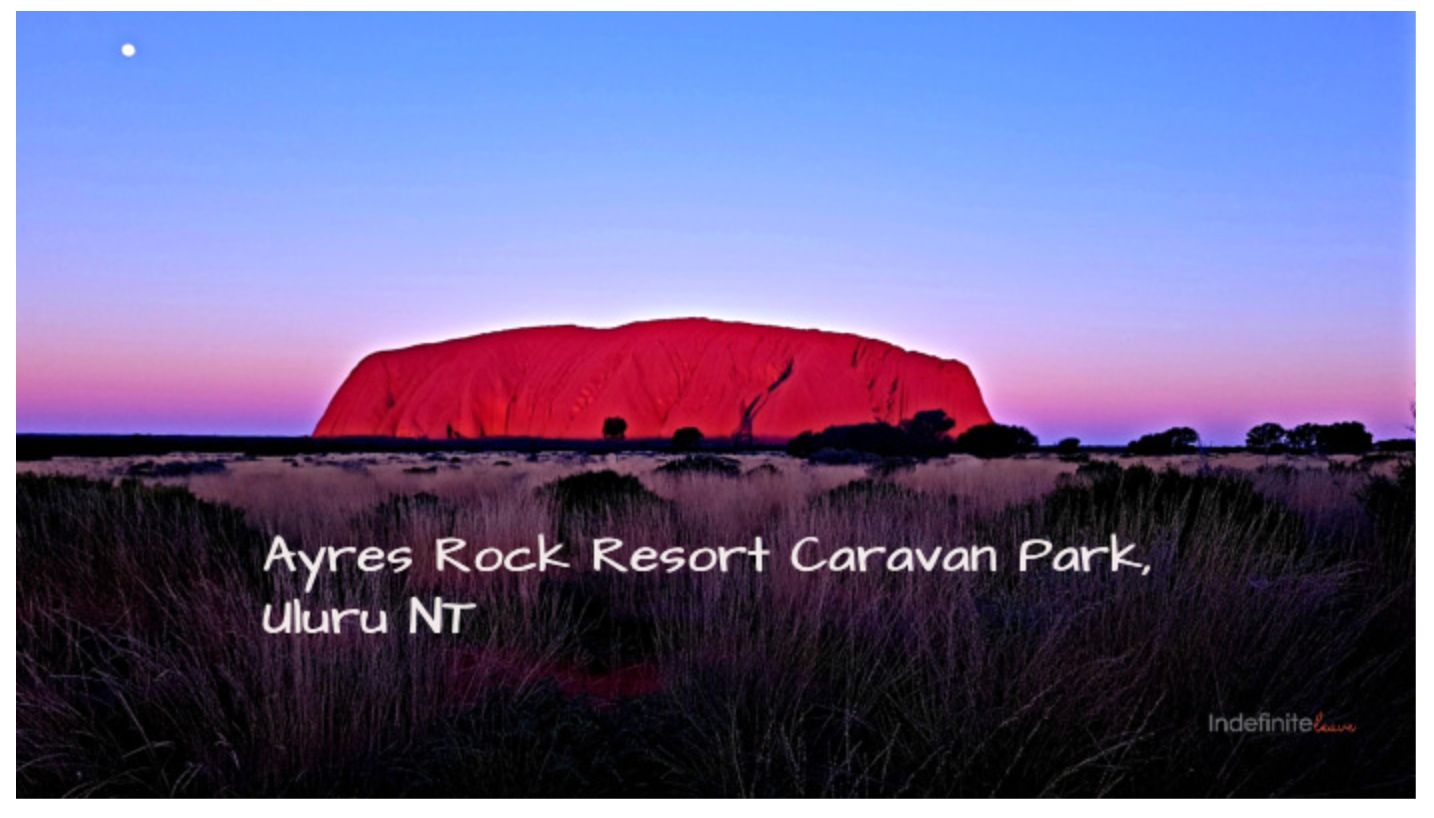

How about a favorite image, a photo, whether science-related or not, that we might find if we walked into your office? Or maybe at home, I see an image behind you that one of your kids probably made, and it’s better than I could make!

(laughs) I just moved into an office right before this shutdown, and I just put a picture of Ayers Rock (Uluru), because it means many different things, to me. It reminds me of a great family adventure. When I was a kid my parents took our family to Australia and New Zealand. I am not great at remembering things from my childhood. But this trip, as a ~7-year-old, was able to stay in my memory. This trip was in December and it was very weird for a California kid to be in ~115 deg F in December. We were up early on Christmas Day and it wasn’t for the stocking we got from the hotel lobby Santa. We went to see Ayers Rock. And I climbed what they called Chicken Rock, which was a little boulder at the bottom because I was too young to actually climb Ayers Rock.

Is Ayers Rock that big one out in the middle of nowhere?

Yes. It’s the largest single rock monolith. It is beautiful how it reflects light to look like different colors throughout the day. And it sort of carries me back to my interest in geology, like how was it created and how is it still there? After all this time, it’s still there. Clearly, other things have been eroded away but it’s still the biggest one. I don’t know if that’s my favorite but it’s in my office, I enjoy looking at it, and it means something to me in that way.

And then we kind of conclude with do you have a favorite quote or something like that, that is meaningful to you? I have one that I like to say: “When all is said and done, there’s a lot more said than done!” (laughs)

That is a good one! (laughs) and so true!

The goal of this series, which was started by Steve Howell, is to enlarge our understanding of each other beyond just our interactions in the office. And to kind of learn about people and their hobbies and their history, how they got here, all the things we’ve been talking about, to get to know each other a little more social than just professionally.

I totally love that and that’s why I’ve enjoyed these. Yeah, I’ve always had athletic interests, my whole life, in sports, everybody says “you’ve got to put your motivational board together” and so you pull quotes from everywhere, but there have been two that I’ve always kind of stuck with from the science aspect and how I’ve viewed life and one of them is from Wayne Gretzky, and I’m not a hockey fan, I don’t watch hockey or anything, but what he says means so many different things to me: “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take”.

That’s a good one!

If you don’t try something how are you ever going to know if you like it? Or if you’re going to do well at it or fail at it? You don’t know, so you’ve got to do it. So it’s always related to me in that way. And then the other one, I think it’s attributed to Albert Einstein. My Dad gave me this quote carved on a board and it is in my office: “If we knew what we were doing we wouldn’t call it research”.

I like that one, too!

I feel like, especially working for NASA, we have this constant pressure that we have to get correct answers. That to me is more of an engineering perspective. You’re going to need a result because we can’t have aircraft or instruments failing on us, but when you’re researching, that’s not the same. A failure IS a result. It’s not a bad thing, and so I feel like it’s part of my job to come up with questions and even answer or understand questions people have, and so I’ve felt like that was part of my job. We don’t always know what we’re doing. If we knew what we were doing it would be real simple to solve, right? We wouldn’t spend decades trying to answer these problems. I think those are the main quotes that always kind of float around and keep me going.

I love them, thank you. You gave us so much and your energy was beautiful. Really nice. Sara and I have benefitted a lot from conducting these interviews because we get to know people and we learn a lot of things because we are not scientists, so we learn the science perspective a little bit. The passion you have is characteristic of people who are doing this kind of work because it’s kind of in your blood, it’s how you operate. So thank you for sharing this time with us. It’s been a delight.

I really appreciate you both reaching out and asking. I’m not good personally going out and talking to people, but I feel like when people look up our branch or our division, and about what we do as a division, I feel like this is such a cool avenue that people can look at and see who really works at NASA and what we do. I mean not just scientifically, but that we’re all normal people. We’re not superheroes, in a way, you know? But what we create and what we solve in the way of problems can be really extraordinary. But we all started somewhere in the past. We were all kids, we all went through middle school and high school. So it helps us in our branches but I also think it is huge for outreach, so people can really see us.

Thank you Amanda.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 2/2/21

To know more about Amanda Brecht’s work.