Let’s start with your early life, where you were born, your childhood, something about your family at the time, what your parents did, any siblings, and then if you recall when you first became interested in what has become your avocation?

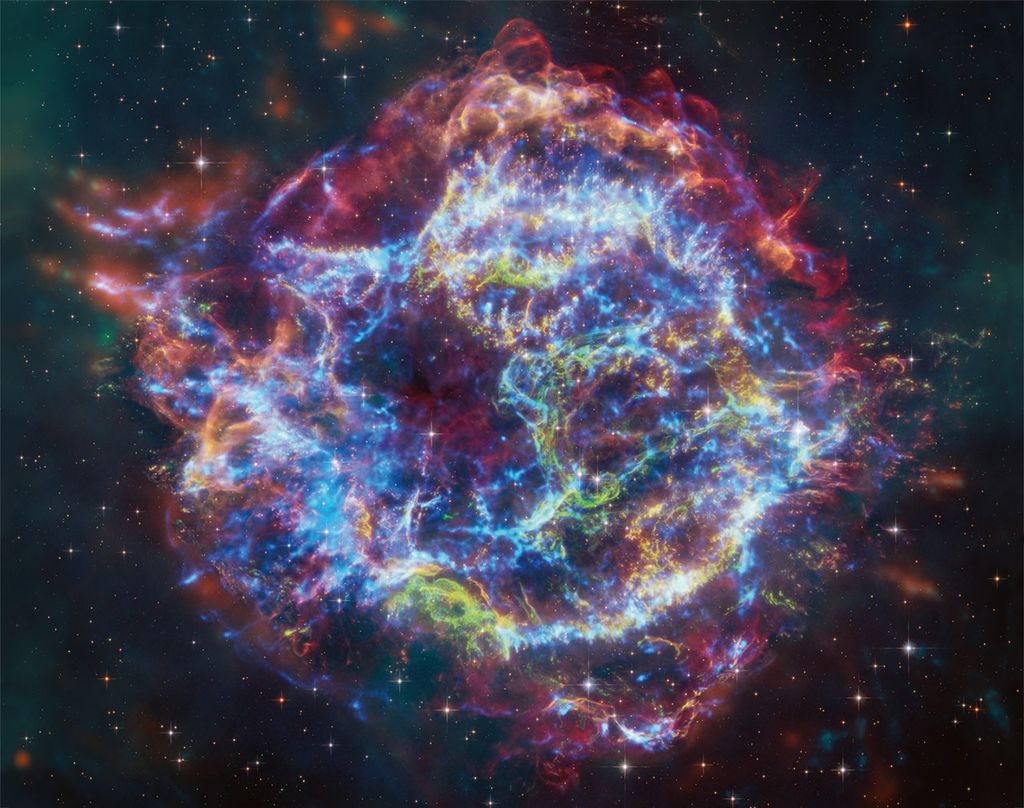

I was born and grew up in East Germany when it was still divided, in Erfurt, in the central east area. That’s where I lived until I was 11’ish. I grew up with an older sibling, a sister three years older than me. My mother worked in a sugar refinery office and my father was a roofer. And then we moved to the area of Hanover in the northern part of Germany and that’s where I stayed until I moved to the U.S. It was about the time, when I was six or seven, that I got really interested in the earth and the universe, somehow. In school I remember seeing maps of the earth and I thought that was really cool, and I always had an appreciation for volcanoes. I liked the way they work, the hot molten rock, the idea that rock could be molten. At that age it was kind of crazy or mind boggling to me. “Oh! Rocks can melt? That’s cool!” And the colors, the smoke, the noise, everything that’s dangerous really attracted me somehow. And that idea just went through me. I wanted to understand how the earth was composed. I knew there was molten rock and I wondered if it was dangerous to me. Like, could the earth just open up and swallow me? These were thoughts I had as a kid. And then I was interested because I wondered if other planets could have the same thing. And that’s how I kind of went into a planetary point of view, with the planets the universe, and the stars. Looking up into the sky, there’s so many things to think about and to muse about.

I was going to follow up on that line because your bachelor’s degree was in geology and your focus seemed to be volcanism and so forth, so what was the connection to planetary? But you’ve explained how that came about.

Yeah, yeah. It just went hand-in-hand, somehow. It could’ve been something different but I thought there was really an intricate connection between the two. If you look at images of planets and you can see the surface, you wonder what’s underneath it?

Can I ask about your sister, what she does?

Yes, all my family is still in Germany. She works at a water treatment facility, checking the water quality for the city they live in. She has a family now, two adorable nieces.

Very nice. OK, so you went to school in Hanover and then you made a leap across the ocean to attend grad school in Missouri. Can you talk a little bit about how that came about?

When I went to Hanover to do my undergrad I had the chance to work in a lab looking at minerals with microscopes in the infrared, looking at water in these minerals and that was cool. And since I was working closely with a professor there, he said “I have a project I need to send students to”, which was with a collaborator and undergrad advisor. The name of that person in Missouri was Alan Whittington and I got a chance to go to the lab to complete some experiments on deforming glass, basically to measure the viscosity of these glasses depending on what the composition was and the temperature. So I got to know Dr. Whittington and I thought well, this is really cool, this is volcanology. Viscosity is the study of how matter flows, and it’s directly tied to volcanoes, so again I thought “Oh, this is really cool”. You can study this and depending upon all the physical properties and chemical compositions of all kinds of lavas that we have on earth, I thought it was really cool what he was focusing on. So I finished up my undergrad and I knew that Dr. Whittington was looking for grad students so I asked him if I could apply to the program. And he said “Of course” and that he had really enjoyed working with me. So that was my way into making the leap over to the U.S. I also had a personal motivation to go because I wanted to be a researcher and I knew that English is the primary language to do research and I wanted to be more competent. I wanted to learn, to write, and to speak in English, so that was my motivation to go out of the country for my PhD. It wasn’t really in my mind to stay here, I would probably come back to Germany, but I ended up staying in this country.

Well your English is flawless I would say, really excellent.

Well thank you. Some people will still call me out on certain things. I’ve been here for 11 years now and sometimes I can hide it but there are some clues that they can figure out that I’m from Europe. Like the way I use my hands for counting, like 1-2-3-4 (demonstrates), and stuff like that. People will say, well, that’s unusual (smiles).

But that’s a pretty straight path actually, getting in to your field. And then there was at some point a connection to NASA, to Ames. Was that the NPP program?

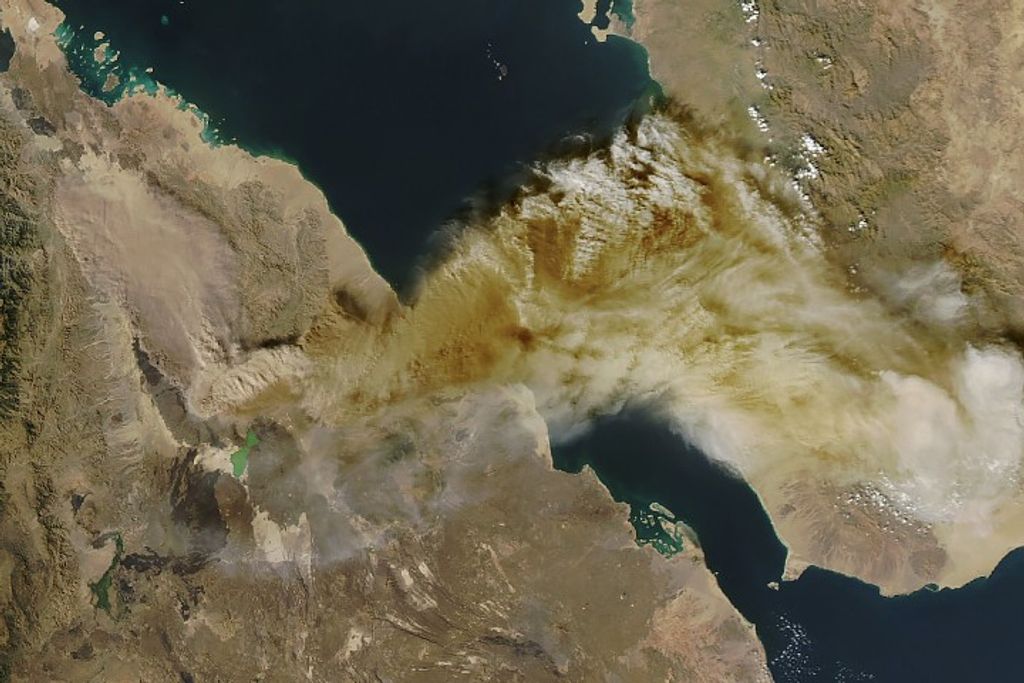

Yes, exactly that was my NPP. When I did my PhD I started out studying lava flows studying the rheology of how they flow on earth. I was in Hawaii, I was in Guatemala, studying volcanoes and I took these rocks back to the lab in Missouri and studied how they flowed, especially those from Hawaii, which is an analog for planetary volcanism. So that was getting me into the path of planetary volcanism and then, based on all these remote sensing data that were collected, I created my own planetary rocks from different chemistries, from Mars, the Moon, Mercury, Io, and so on. I studied these which helped solidify my track into the planetary science community, writing papers, abstracts, and presentations. Then, in my final year of the PhD, I think it was 2015, I saw an ad for an NPP position with the FINESSE team. That stands for Field Investigations Enabling Solar System Science and Exploration. It was led by Jen Heldman and Darlene Lim at Ames. It interested me because, from the description, it looked like a perfect fit for volcanology in the NPP program. In the end, by writing that research proposal of the work that I wanted to do, which convinced the reviewers of being worth investigating. I got accepted and that was my way into Ames.

And was one of those two your advisor in the NPP?

Yes, both served as my post-doc advisors.

We also ask, regarding the discipline that you’re pursuing, how it relates to or supports the NASA mission and how it is defended to the taxpayers who pay all the bills for NASA? In other words, why is it important?

Yeah, yeah. That’s a very good question. I think about that often, about how the work I’m doing is important to NASA. So first a bit of a disclaimer: once I got to Ames I took on different paths, not really doing volcanology as much anymore. At the time that I started on my NPP I was doing lava rheology, basically how rough volcanic surfaces are and how understanding them is important because if you want to land somewhere that’s volcanic, you want to know what kind of surface that is. Understanding how the lava flows and under what conditions it formed rough and smooth surfaces, has implications for missions going to these places. And if you can remote sense them, based on their roughness, you may even tell what the rock is made of, whether it is porous or not, and whether it breaks easily. That has implications for where you want to go, and helps determine if it is hazardous terrain or not. So that has implications to why this is important to NASA. And then once I got started in the NPP and had the opportunity to work with a lot of really good people at Ames, who offered me opportunities to do other things that I hadn’t done in the past, like using handheld instruments/spectrometers, I call them laser guns. You hold them in your hand and place the rock in front of them and pull the trigger and the spectrometer essentially sends out a light beam or some even send x-rays. From the returned signal you can determine the chemistry of the rock, which can give an idea of the minerals that are in there, or its origin, so I studied that, too. It was really different from what I had been doing but it kind of aligned with the theme of what I was working on. And it has implications for what kinds of tools we could take to these planetary surfaces that weren’t available fifty years ago when we went to the moon with Apollo. Now they are available should NASA invest in them for the next generations of astronauts? That was one part of the work I did.

Did you collaborate at all with David Blake and his Che-Min instrument that he put on Mars?

No I haven’t done that yet, although I’ve follow it. It becomes more important for what I’m doing now, since I want to build an instrument that has an XRF unit included, so I’m getting close to looking at what David Blake did, how he put things together, made it work, and sent it to Mars.

How has the pandemic affected your work abilities? Are you able to do your job pretty much fully remotely, not being able to go in?

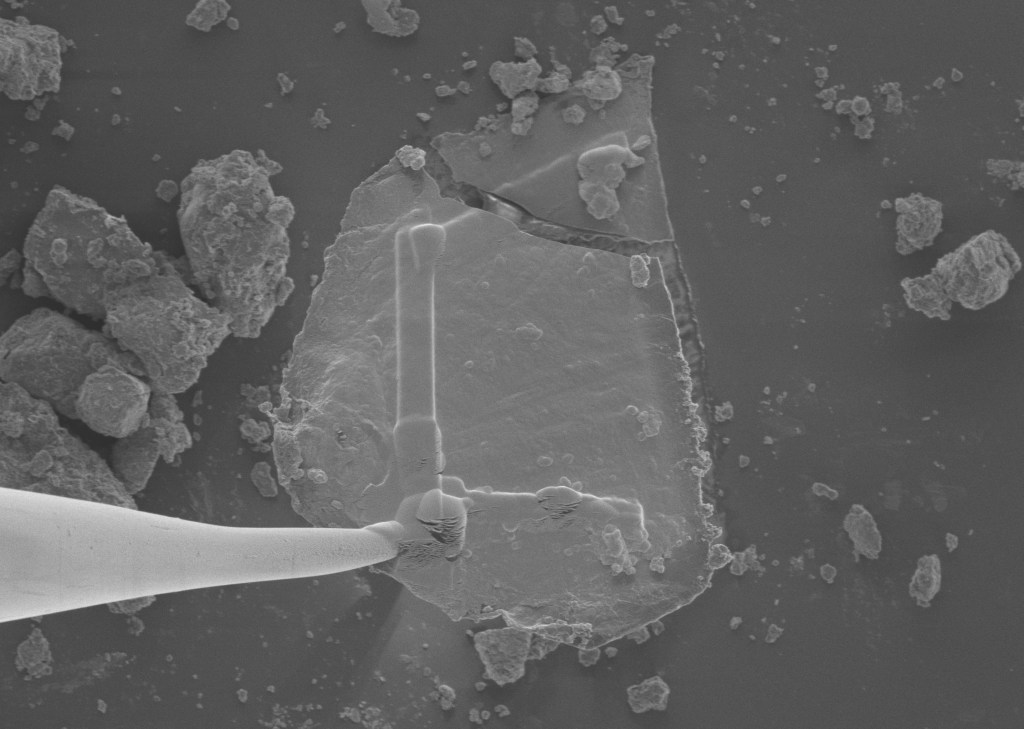

There are two sides to this question. The honest answer is that I’m an experimental person and I need to be in a lab to produce data and look at samples for the projects I’m working on. I’m currently looking at pristine Apollo 17 moon rocks that no one has ever looked at before, they’ve been locked in a vault for fifty years. There were plans to send out Apollo exploration samples to teams, a consortium of teams that I’m the PI for, prior to the pandemic, right before it hit. So that meant the result is delayed and I couldn’t do that work at all. With that being said, I’m also an experimental person looking at building up a lab to measure the viscosity of lavas. I was about to be finished just when the pandemic hit and that had to come to a halt. So the answer is, I couldn’t do the work that I used to do because I’m an experimental person and I need to be in a lab. That was a big worry: how it would affect my career and how long I would have to wait to continue that work. On the other hand I’m not a pessimistic person, worrying that I don’t know what to do now. I had other ideas and the first thing I did was to write up papers that I hadn’t had time to write because I was constantly in the lab doing more work. It piles up, the data piles up, and I hadn’t had a chance to analyze it for two or three years, so I worked on papers, to get them out and published, and I think that was a very good thing to do. I was very happy that I could review the data and share them with the science community. I shouldn’t have waited that long in the first place but it always happens. You collect here and then you have ideas of what you want to do and you get sidetracked. So that meant I could be productive during the pandemic time, just not the way I planned it. I had to do a lot of replanning of my time. I took advantage of the time to be more creative and come up with new ideas. One of them was to build an instrument to send to the moon. There were things that I couldn’t do but I substituted for other things that I wanted to do and never had time to do. Luckily I was able to go back into the Ames lab in the fall of 2021, through the approved process, because the Apollo 17 samples were ready to be sent by JSC to the lab so I could start the work there, and it looks very promising. So the outlook is good that I can continue the work that I wanted to do two years ago.

Excellent! You’re excited then about Ames opening up and you being able to get back to your lab.

Very much. I’ve had a couple of chances to go in because we’ve had pumps running in the lab and wanted to keep water out of the vacuum system so we had to keep them running and make sure they weren’t running hot or running out of oil so they wouldn’t catch on fire or break down. But that was only for an hour, once a month. It was really nice to be in the lab again but also very strange because there was nobody there and it’s kind of an odd feeling when no one is around.

Yes I understand. So what do you like best and least about your job?

A: Well the best thing is that I do what I really like or love to do. I am creative and I am doing work that seems to be appreciated by other people and seems to be important work that gets funded, so I’m happy that I have the chance to do that and exercise creativity to come up with new projects. And the people that I’ve met at Ames have taught me so much. I look at what they do, how they handle things and it’s really inspirational, what they work on and especially what their paths have been. So the people that I work with and the projects that I work on are very satisfying.

You are still what I would consider an early career researcher.

Yeah, I have a couple more years left and then I guess I would be considered what? Midcareer?

Yes. Have there been any research findings or interesting things, high points, or something unexpected that you’ve come across in your research so far?

Well, I think that is starting now with the Apollo samples that I’m going to be working on. It’s thermoluminescent studies. We heat up a piece of, well I call it dust for lack of a better term, and it emits light at different temperatures. We call it a glow curve, you ramp it up to 500°C and that contains information about the radiation and thermal history of the sample, which is important because if you’re looking at resources you want to understand what the history is. Was it cold here for long enough, for example? Things could have built up if it was in a permanently shadowed location, so it’s that kind of work. And that’s just starting as I’ve been able to go back to the lab. I have had a couple of findings, because these rocks were sealed away on the request of thermoluminescence researchers fifty years ago. They said “NASA, please put these into the freezer until we can get a chance to look at them again”. And the first finding I made at LPSC I n March of this year (2022) is that yes, these rocks are still very strongly luminescent, they still glow when you heat them up, we didn’t lose the signal, which has an important implication because there was a debate back in the early ‘70s when the first teams looked at the thermoluminescence of the lunar rocks, in the first ones they collected by hand, whether the TL signals would fade away quickly. We had no idea based on three years of work in the early days, and now fifty years later to see them really, really, glowing brightly is significant. I’m still doing the kinetics so we can understand much better how the signal is preserved and then use that to make temperature estimates of the past, so that was a big finding. I have to do more research in the lab to say more about it but that was a big thing, that there are still very usable measurements to be made.

Well you’re obviously doing something that you have your heart into but let me ask you an off-the-wall question: if you weren’t a NASA researcher have you ever thought what your dream job might be?

Yeah, I’ve had a couple of ideas. I really like glass. It’s kind of like volcanology but in terms of art. So glassblower is one thing, making sculptures out of glass, vases out of glass. I like to play with the coloring and I just like the material. it’s shiny and clear and you can make it not clear, diffused. You can make all kinds of crazy things, you can express yourself in many ways and forms and shapes. I always called that my second career.

Very interesting and logical for sure. You’ve had what appears to be a fairly straight path into your career field but what advice would you give to a young researcher who would like to have the kind of career that you are having?

Oh, that’s a good question. I would say let it flow, don’t force yourself into a corner. Be open to things. Things happened to me because I was open to people and what they did, so being open to meeting people and understanding what they do is important. Also not being afraid, because the future is often uncertain. When I was a grad student I wondered “what comes after grad school for me?” I had an idea of my dream career and it was pretty nice. And then I got to Ames and now I’m doing all these things that are even better than I could have thought of. There’s probably more but I didn’t need to set my career in stone at the end of grad school. That is something that would be worth mentioning to a prospect, to a grad student. There’s more to come and you probably won’t know what it is. It will come to you so don’t be afraid.

That’s excellent advice. Do you want to say anything about your family? Are you married? Kids, pets, trips, things like that, things you like to do?

No I don’t have a family. I don’t have kids, I don’t have pets. I thought about getting a cat, during the pandemic, something that purrs and calms you down, but I didn’t really need it. I like to go on road trips, to drive around, get out into nature and admire nature and I just didn’t want to lock myself out of a two week trip because I had a pet to take care of.

That’s right, that’s a downside.

That’s the only reason that held me back from having like a cat. I would think “I don’t want to give you away or leave you with someone for a long time”. But road trips and getting out into nature is something I really like to do. And photography, that’s something I also like to do. Not really professional but capturing the moment and the light and more recently I’ve wanted to kind of keep that visual interest going so I’ve been doing painting and art. I wouldn’t really call it art, but like sketching on an iPad. If you have a picture you can experiment with different colors and brushes, make it a picture somehow. But I wouldn’t call myself an artist! (laughs).

Well you do have family back in Germany you said. Have you been able to connect with them or even visit them during the pandemic?

Actually I’ve had family out here for the past two weeks. My mom came to visit with my niece who is 15. It was the first time for my niece to be in the U.S. so it was quite an exciting trip for her. My mom has been here in California a couple of times since I moved out here six years ago, so it was really nice to see family again for the first time since the pandemic. 2019 was the last time I saw them in person, before that it was all phone calls, so having them here just sitting around and talking, making food together, eating, sitting around the fireplace at night, playing games, these kind of things are really nice and I really missed that. Not really knowing how much I missed it but I missed it much more than I thought. So it was very nice.

That’s understandable and I assume that some of these phone calls were FaceTime where you could actually see each other

Yeah, yeah, exactly and especially during the holidays, like Christmas, because I didn’t go back. Traveling at those times is so busy, everyone wants to go everywhere. And I was afraid that with the Covid and so forth I might possibly get shut out from returning to the U.S. and not be able to come back here and do my work and many other problems could come up so I just stayed here and hoped for the best. And the best happened! They came just recently and visited me!

Your patience was rewarded! Now, let me ask: what do you do for fun?

I like to be active. I go to the gym. That’s probably the most routine thing I do that I enjoy doing. Blowing off some steam after you’ve been sitting at your desk for eight hours a day, you need to move around and I was very happy when the gyms reopened. For fun? I like to cook a lot, I like to do pralines. Making food is something that I like to do for fun and then as I said, painting and digital art, scribbling around, that’s what I really like to do, while sitting around at night. It’s relaxing and you can shut off the brain a little. Just to scribble around and make some waves and lines and see what comes out. A lot of things during the pandemic couldn’t happen, traveling was really not an option, but now that things have eased up a bit, travel may be a little more on the radar this summer. So those are a handful of things that I like to do.

You mentioned an interest in the art that you’re doing. Do you have any other talents or musical instruments or sports or any such thing?

No, nothing at all. I’m not musical at all. I really like the piano. I always wanted to take lessons but I’m kind of afraid of it because I think I would forget too quickly how to do it. And I would probably get upset because I would always do it wrong. I probably shouldn’t say that but I still type with two fingers, so imagine me now playing the piano! I would be using one or two fingers here and there, instead of the right way, so I probably shouldn’t really try.

You’re a lot like me I think. I didn’t practice much when I took piano lessons as a kid and now I wish I had. But it does take a lot of practice and effort.

Yeah and that’s probably like a lot of people.

What accomplishment are you most proud of in your life that’s not science related?

I think the courage as a young adult to go into a country and commit to doing a doctorate in a language that I didn’t speak and making it. I mean I had listened to English but I was nowhere fluent enough to have a conversation like we’re having now. Also not coming from an academic household. As I said of my parents, my father was a roofer and my mom worked in a sugar refinery office and having made that leap as the first person in the family to go to a university and get a doctorate degree, I didn’t think I would go that far, that I would stop at the master’s level. And doing it in another country. But somehow my work left an impact and NASA wanted to have me as an NPP. I think that was the biggest accomplishment for myself.

That is indeed a very impressive accomplishment.

Just the courage that I had in myself to step into the unknown. I think that is my biggest accomplishment today. I’m really happy and proud that I tried it. There were moments that I just wanted to quit and go back, but I didn’t. I persisted, and looking back that really was an accomplishment for my personal self.

It definitely was and continues to be. How about this? Who or what inspires you?

it’s inspiring to know that I felt this motivation to step into the unknown. I’m not sure what’s behind it but I want to know things we don’t know and why we don’t know them. And to understand the concepts behind them. That’s the motivation for me to do what I do.

I like that. I’ve asked that question dozens of times and that’s the first time I’ve gotten that answer, and I think it’s perfect. You are certainly in the right field, trying to understand what we don’t know and reveal the unknown, and that in itself is inspiring.

Well I’m really curious about things,

Wonderful! Well, we’ve tracked through most of the items that I generally poke at but one more question is: do you have a favorite image or picture, something about your work or something in your life that you find motivating or interesting, that might, for example, be on your wall in your office? Let me broaden that a little by saying that when we get ready to post this on the website we’d like to have some pictures of the things that you’ve talked about, things that represent your life and interests, your career, to go along with it, so you might be thinking along that line as well. Just so other people can get a sense of your life beyond just your work in the lab. So be thinking about providing some pictures for the post when we finally do it. And also a quote, something that you find inspiring or clever or motivational. Do you have a favorite quote?

A: No, not a favorite quote. I like a lot of them, one of them is “Strive not to be a success, but rather to be of value” by Einstein.

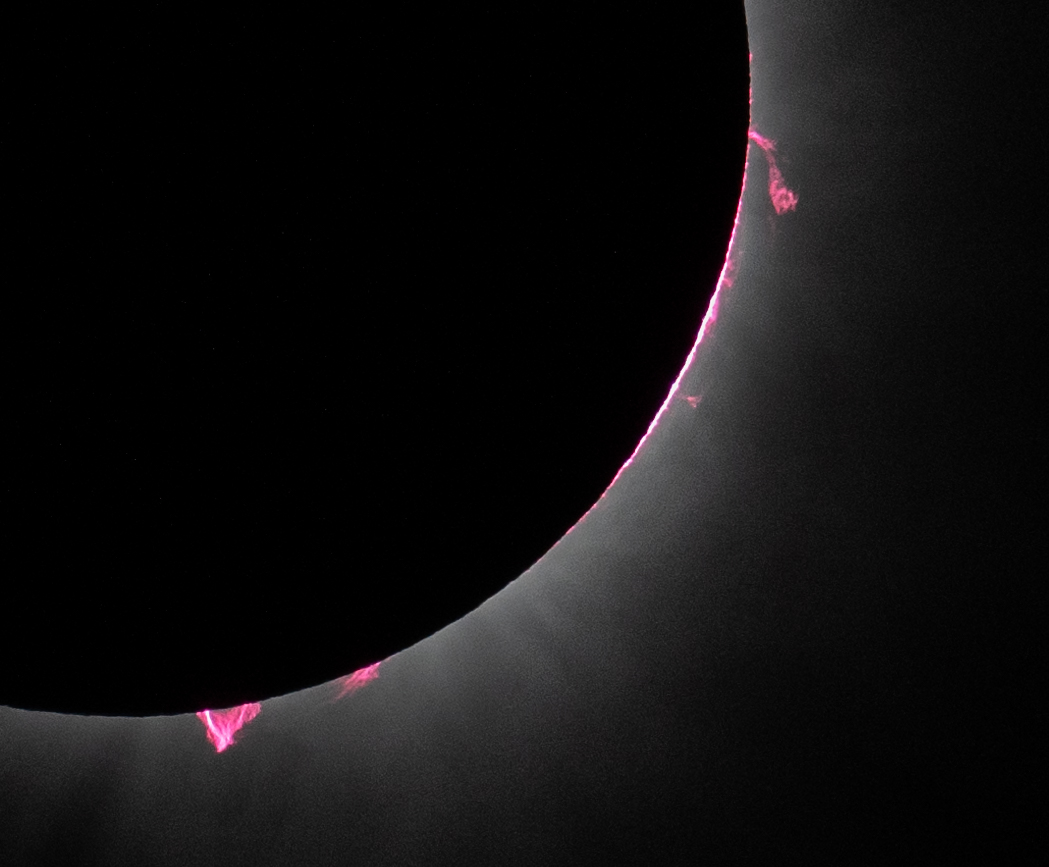

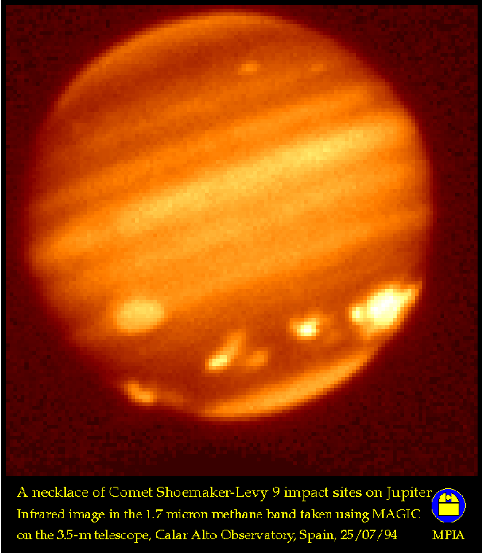

One of my favorite space images is the collision between comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 and Jupiter in 1994. Very spectacular event to witness, and seeing these images and documentaries about it got me very interested in planetary science as a young kid. The idea that rocks as big as mountains can fall from the sky in our cosmic neighborhood is just mind-boggling, and also unsettling.

Is there anything that you wish I had asked that I didn’t ask?

No. I think you’ve asked a lot of good questions, not so much related to science but about me.

Well that’s what I was trying to do.

I think that I didn’t give you an answer to one of your questions. You asked about what I like best and least about my job and I don’t think I touched on what I like least. And that is: I don’t like the deadlines (laughs). Short answer!

Well, thank you. This is been interesting and I’m sure that others will find it interesting as well.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 4/20/22