Although Dr. Elkins-Tanton is the Principal Investigator for NASA’s Psyche mission, the first NASA mission ever to explore a metal asteroid, she never expected her team’s mission would be selected by NASA officials.

Although Dr. Elkins-Tanton is the Principal Investigator for NASA’s Psyche mission, the first NASA mission ever to explore a metal-rich asteroid, she never expected NASA to select her team’s mission. Hundreds of people had labored for years on the five final concept studies: VERITAS, DAVINCI, Lucy, NeoCam and Psyche. This was Psyche’s first time undergoing the proposal process.

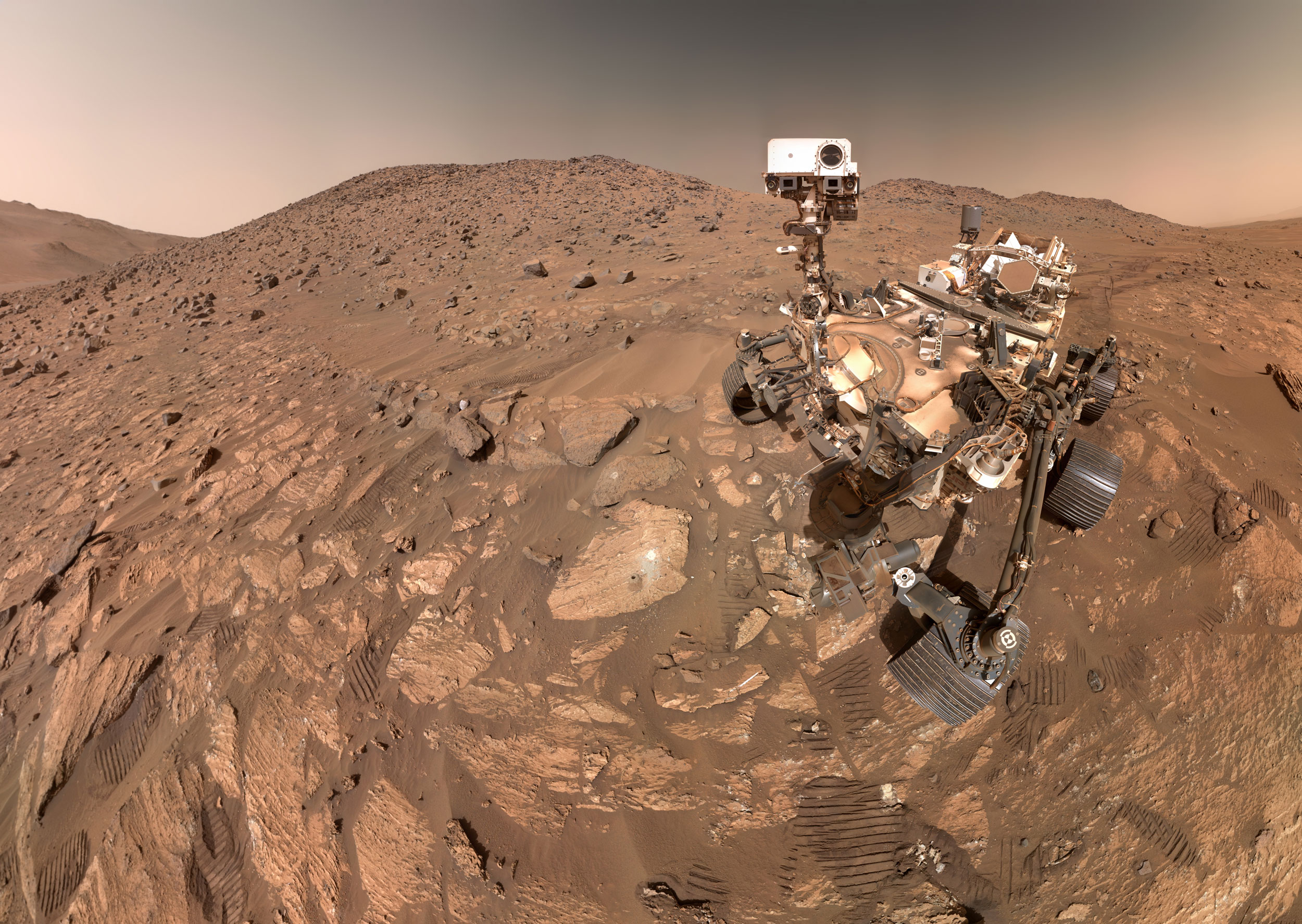

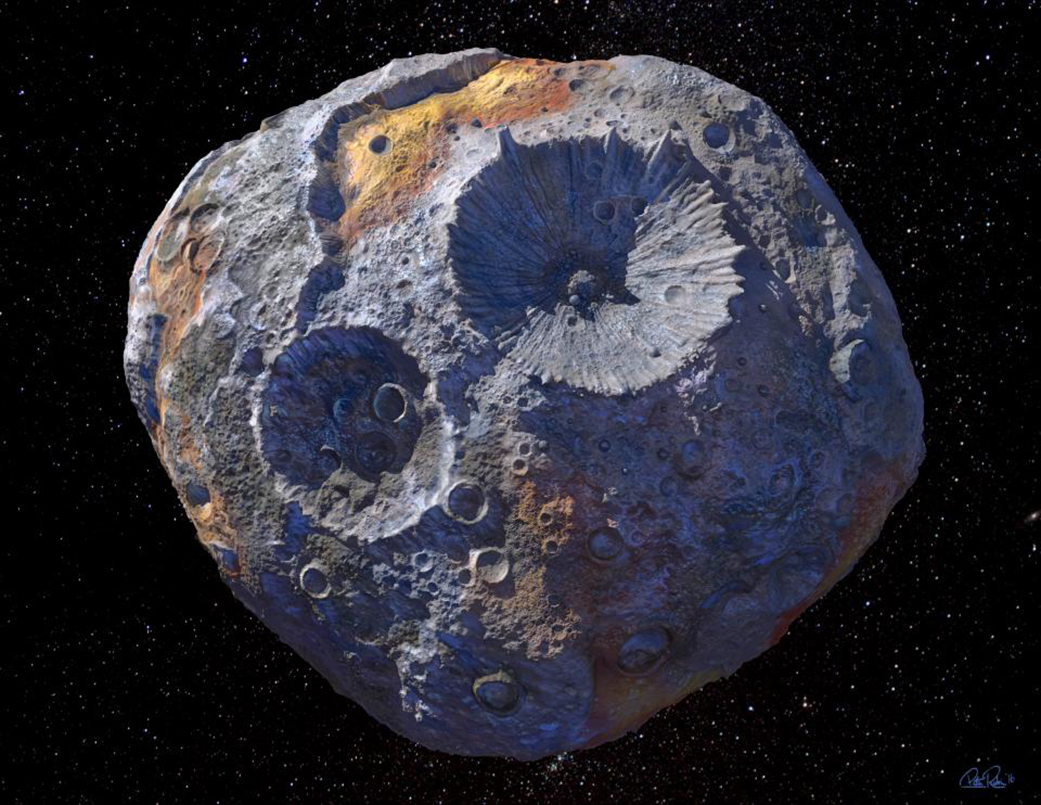

The Psyche mission is a journey to a metal-rich asteroid orbiting the Sun between Mars and Jupiter. What makes the asteroid Psyche unique? Because we think it might be the exposed nickel-iron core of an early planet, it could provide clues on the building blocks of planet formation.

“Maybe in the grand scheme of human endeavor, working for six years on something you may never get the chance to do is a pretty long time,” she reflects. “But in the grand scheme of NASA missions, of course, six years is not a long time to work on a mission. So, we were fully expecting to work on it for another six years and another six years and another six years, helping it be selected for flight.”

Despite the Psyche team considering themselves to be “the extreme underdog,” Dr. Elkins-Tanton woke up to a startling phone call from Dr. Thomas Zurbuchen, Associate Administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, in early January of 2017. At first, the lack of cell reception in the hills of Massachusetts threatened to cut off their conversation, but Dr. Elkins-Tanton managed to direct Dr. Zurbuchen to the landline.

That’s when she received the life-changing news: Psyche had been selected.

“Right after letting us know we were selected, the first thing [Dr. Thomas Zurbuchen] said was, ‘I want you to re-propose a student collaboration that’s much more radical and innovative and large.’” she recalls. “After we hung up I just had to draw my breath, because then I knew: the rest of my life was going to be different.”

She was right: for the first time in her life, she was locked into working on a project for the next decade if not longer. A space mission typically has six phases, A-F. The Psyche Mission is currently in “Phase C,” where the science and engineering teams are designing, assembling and testing the different instruments that make up the spacecraft — including a new laser communication technology that encodes data in photons (rather than radio waves) to send back to Earth. Psyche is scheduled to launch to space in August of 2022, where it will travel using solar-electric propulsion to arrive at the asteroid in early January of 2026.

As someone with a self-described “curvy” career path, this decade-long venture was an extreme departure from the norm.

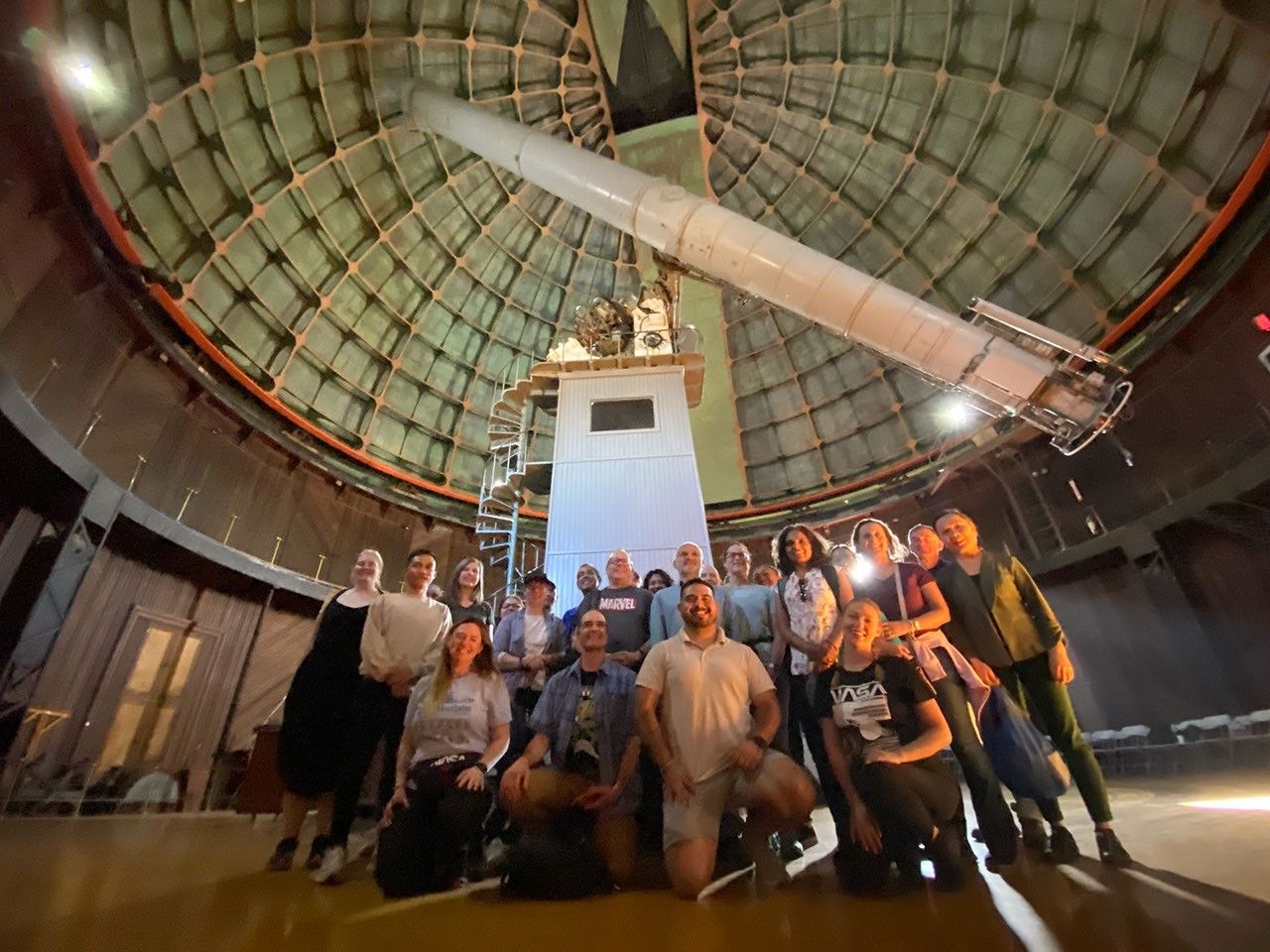

“I was not one of these people who just knew from the age of ten that I wanted to be a planetary scientist or work on NASA missions,” laughs Dr. Elkins-Tanton. “I think the archetypal moment you’ve probably heard before is: ‘I looked through a telescope when I was ten and I saw Saturn with my eye and from that moment on…’” she muses. “I’ve actually heard multiple people tell that exact story…And so I’m fond of saying, I did actually look at Saturn through a telescope with my eye and it was really fabulous — and I still wanted to be a veterinarian after the experience.”

Despite wanting to be a veterinarian as a child, Dr. Elkins-Tanton earned her Bachelor of Science in Geology and Master of Science in Geochemistry from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After working in business forecasting for 8 years, her career path swerved again when she took a job lecturing in Mathematics at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. It quickly inspired her to go back to school for her terminal degree.

“The thing that I really loved at that moment consciously was the idea that in academia, not just the teaching side but especially the research side, that you can always ask a bigger and more challenging question,” she says. “I didn’t want to end up with a job that became regular or predictable. Sometimes that’s really lovely for people and for me it was just murderous. I needed to always be able to challenge myself further.”

However, despite enjoying the challenging nature of graduate school, Dr. Elkins-Tanton sometimes felt as though she had had “too many strikes against [her]” to have a successful career. Because of her time spent in business, she was ten years older than most of her cohort. Plus, she was the only single mother of the 120 people in the program.

“I have this passion to try and encourage everyone, because I think that the reason someone may feel excluded or that their voice isn’t heard…might be invisible. It’s not just a bi-modal gender issue,” she says. “What I’d love to do is send a message to anyone who feels like they might not be in the ‘in-group,’ that you are welcome. Just keep at it.”

Her experience in academia encouraged Dr. Elkins-Tanton to work to implement a culture focused on “interdisciplinary collegial collaboration rather than cutthroat competition.” Since returning to school, she resented the way professors were prone to look out for themselves while seldom celebrating the successes of others. It was a culture that she was determined to change once she got the chance.

She finally got that chance when she became the Director of Arizona State University’s (ASU) School of Earth and Space Science on July 1, 2014.

“One of the reasons I came to ASU was that there already existed a pretty great culture in the School of Earth and Space Exploration…I had a sense that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” she says. “As people gain power in their careers they really try to use it to support other people. We see it happening. It’s kind of magical.”

Dr. Elkins-Tanton was further inspired to take the idea of a collaborative team culture to another level: in 2017, she and ASU President Michael Crow started the Interplanetary Initiative. The motivation of the Interplanetary Initiative is to revolutionize how research teams work by bringing all disciplines together to create a positive space future for humankind.

“If we are going to become an interplanetary species, we need sociologists and psychologists and artists and writers,” Dr. Ekins-Tanton says. “We need everyone else at the table — not just scientists, engineers, [or] government.”

The model differs from the traditional form of academic research and what Dr. Elkins-Tanton calls the “hero model,” because it holds that there is no single leader who directs the flow of work. An interdisciplinary group brainstorms the big questions that must be answered to accomplish a specific goal, and then teams are created to reach certain milestones. The goal of the method is to avoid incrementalism and to build a forward-thinking community around the future. The Interplanetary Initiative is currently looking for active partnerships.

“On the Psyche team, a big part of the motivation for making a collegial and collaborative team culture is in service of one of our little mottos: ‘The best news is bad news brought early,’” she laughs. “Because if you need to fix it so it’ll work before it launches, you have to know about it.”

Dr. Elkins-Tanton hopes that everyone on the Psyche team, which consists of over 800 scientists, engineers, project managers, schedulers, financial modelers, graphic designers, and marketing leads from dozens of research organizations, feels comfortable enough to sit down at the table and speak up at meetings.

“It’s clear from my story already that I never, until very recently in my life, had any single big vision that I was really working towards,” says Dr. Elkins-Tanton. “I think it’s okay to even not be sure you want to do this forever. Pursue the beautiful opportunity in front of you. And don’t feel like you have to commit for the rest of your life. Just keep moving forward.”

By Thalia Patrinos