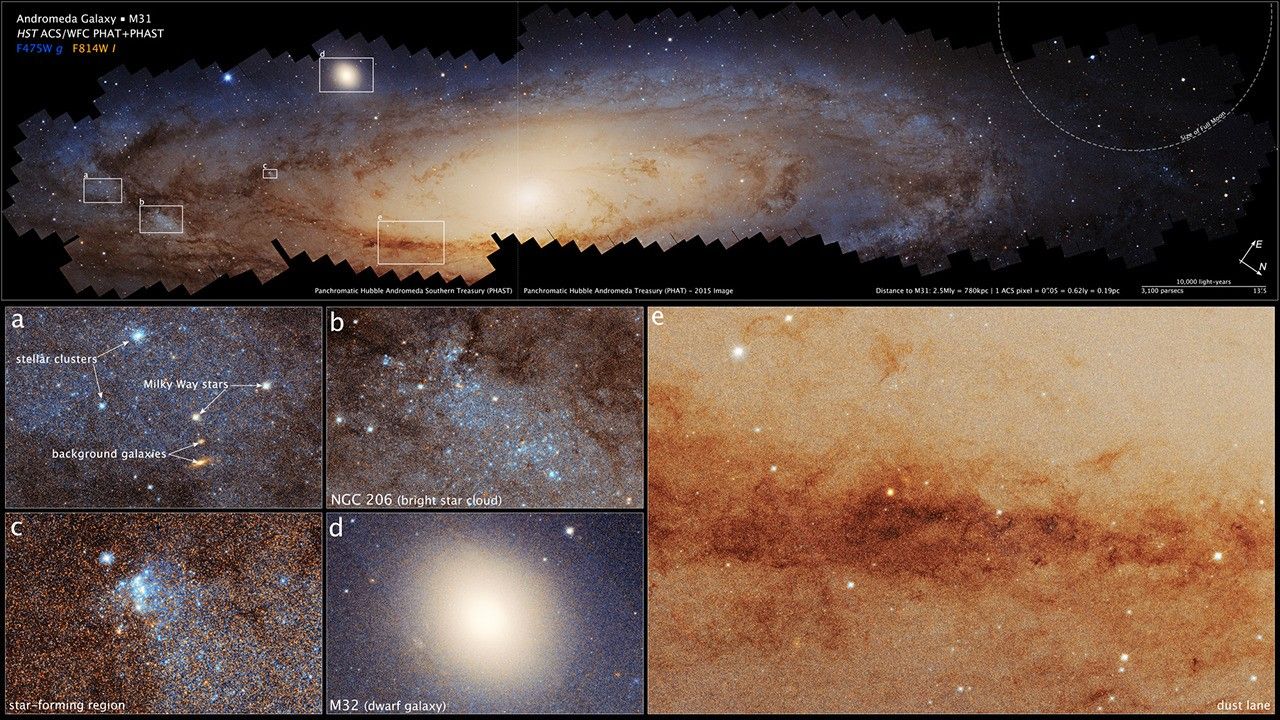

Once you leave the majestic skies of Earth, the word “cloud” no longer means a white fluffy-looking structure that produces rain. Instead, clouds in the greater universe are clumpy areas of greater density than their surroundings.

Space telescopes have observed these cosmic clouds in the vicinity of supermassive black holes, those mysterious dense objects from which no light can escape, with masses equivalent to more than 100,000 Suns. There is a supermassive black hole in the center of nearly every galaxy, and it is called an “active galactic nucleus” (AGN) if it is gobbling up a lot of gas and dust from its surroundings. The brightest kind of AGN is called a “quasar.” While the black hole itself cannot be seen, its vicinity shines extremely bright as matter gets torn apart close to its event horizon, its point of no return.

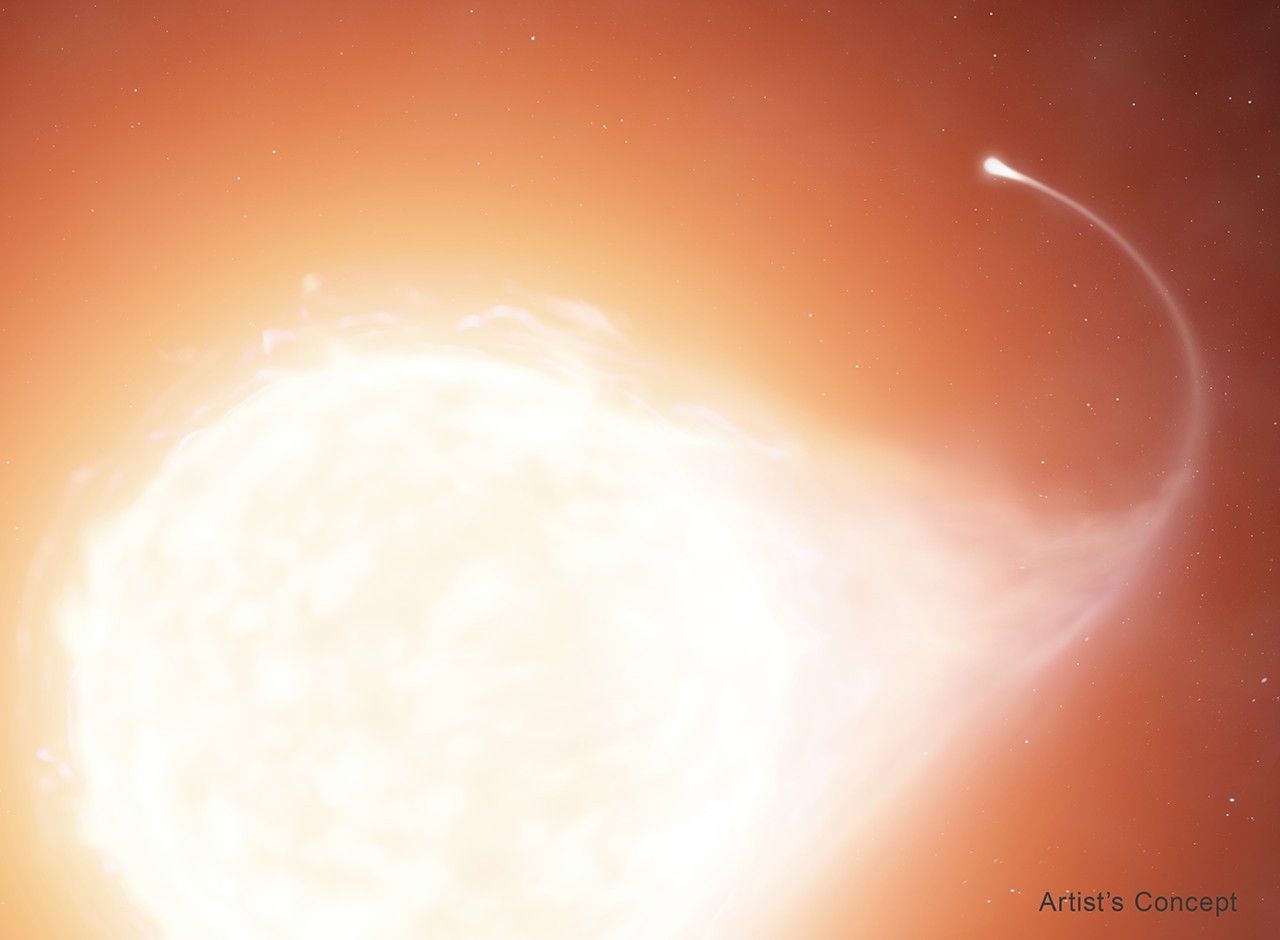

But black holes aren’t truly like vacuum cleaners; they don’t just suck up everything that gets too close. While some material around a black hole will fall directly in, never to be seen again, some of the nearby gas will be flung outward, creating a shell that expands over thousands of years. That’s because the area near the event horizon is extremely energetic; the high-energy radiation from fast-moving particles around the black hole can eject a significant amount of gas into the vastness of space.

Scientists would expect that this outflow of gas would be smooth. Instead, it is clumpy, extending well beyond 1 parsec (3.3 light-years) from the black hole. Each cloud starts out small, but can expand to be more than 1 parsec wide — and could even cover the distance between Earth and the nearest star beyond the Sun, Proxima Centauri.

Astrophysicist Daniel Proga at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, likens these clumps to groups of cars waiting at a highway onramp with stoplights designed to regulate the influx of new traffic. “Every now and then you have a bunch of cars,” he said.

What explains these clumps in deep space? Proga and colleagues have a new computer model that presents a possible solution to this mystery, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, led by doctoral student Randall Dannen. Scientists show that extremely intense heat near the supermassive black hole can allow the gas to flow outward really fast, but in a way that can also lead to clump formation. If the gas accelerates too quickly, it will not cool off enough to form clumps. The computer model takes these factors into account and proposes a mechanism to make the gas travel far, but also clump.

“Near the outer edge of the shell there is a perturbation that makes gas density a little bit lower than it used to be,” Proga said. “That makes this gas heat up very efficiently. The cold gas further out is being lifted out by that.”

This phenomenon is somewhat like the buoyancy that makes hot air balloons float. The heated air inside the balloon is lighter than the cooler air outside, and this density difference makes the balloon rise.

“This work is important because astronomers have always needed to place clouds at a given location and velocity to fit the observations we see from AGN,” Dannen said. “They were not often concerned with the specifics of how the clouds formed in the first place, and our work offers a potential explanation for the formation of these clouds.”

This model looks only at the shell of gas, not at the disk of material swirling around the black hole that is feeding it. The researchers’ next step is to examine whether the flow of gas originates from the disk itself. They are also interested tackling the mystery of why some clouds move extremely fast, on the order of 20 million miles per hour (10,000 kilometers per second).

This research, which addresses an important topic in the physics of active galactic nuclei, was supported with a grant from NASA. The co-authors are Dannen, Proga, UNLV postdoctoral scholar Tim Waters, and former UNLV postdoctoral scholar Sergei Dyda (now at the University of Cambridge).

Media Contact

Elizabeth Landau

NASA Headquarters, Washington, DC