Throughout history, humankind has shared an innate trait – the desire to explore. Prehistoric men and women may have stood curiously at the opening to caves and wondered what was over the next hill. Centuries later, a teenager in New England envisioned a trip to a distant planet.

In the autumn of 1899, 17-year-old Robert Goddard climbed a tall cherry tree at his home in Worcester, Massachusetts. As he gazed into the sky, Goddard recalled how he was inspired by the works of authors such as H. G. Wells.

“I looked toward the fields at the east,” he said, “imagining how wonderful it would be to make some device which had even the possibility of ascending to Mars.”

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, to explore is to “conduct a systematic search or to travel over new territory for adventure or discovery.”

Goddard was not alone in his desire. Over millennia, human ventures have led to navigating the seas, discovering new lands, conquest of the skies and, now, the exploration of space.

In his high school graduation address, Goddard expressed his belief that a vision for the future can be captured.

“It has often proved true that the dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow,” he said.

Goddard dedicated his life to inventing that “device” that could, one day, reach the Red Planet. On March 16, 1926, he successfully launched the world’s first liquid propellant rocket. What followed was his development of basic rocket technology used by NASA for decades.

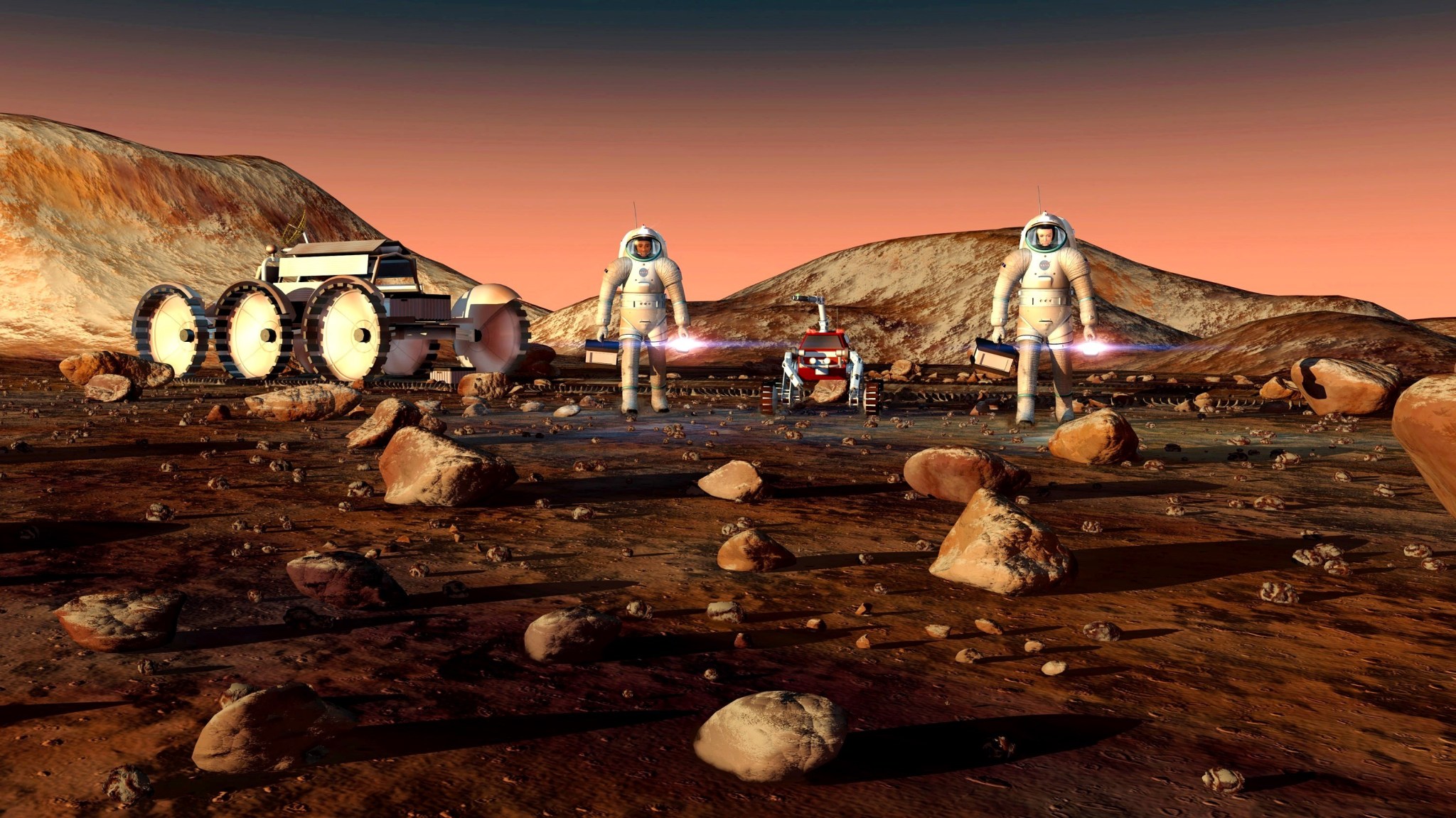

Building on Goddard’s research and that of those willing to explore over the next hill, NASA today is closing in on his dream of a trip to Mars.

Navigating the Seas

Throughout human history, the spread of civilization has been led by people who wanted to explore. Ancient voyagers included the Phoenicians, whose tin artifacts indicate they may have traveled as far as Britain. The Carthaginians explored the western coast of Africa. Greek travelers were the first to circumnavigate Britain and explore what is now Germany.

Among the greatest early explorers were Chinese mariners six centuries ago. A massive armada of nine-mast ships navigated west to Ceylon, Arabia and East Africa.

The leading Chinese pioneer was Zheng He who sailed using a magnetic compass invented in China centuries earlier. During his seven expeditions, he established a broad web of valuable trading routes from Taiwan to the Persian Gulf.

By the early 1500s, however, the Chinese navy was reduced to one-tenth of its size. As the policies of China’s government turned inward, the navy was ordered to destroy the larger classes of ships, sending the nation into a centuries-long policy of isolation. Over time, the expertise to construct and navigate large ships was lost along with advances in technology.

In 1492, the European Age of Exploration began when the king and queen of Spain financed a voyage by Italian mariner Christopher Columbus. His expedition was to sail west from Europe seeking a more efficient route to India. His commitment to venture into the perils of the unknown has been shared by explorers throughout history.

“You can never cross the ocean unless you have the courage to lose sight of the shore,” Columbus said.

His willingness to do so resulted in the discovery of a “new world.”

This Age of Exploration has been hailed by many historians as one of the most important periods of geographical findings. From the 15th century until the 17th century, the voyages of explorers such as Ferdinand Magellan, Juan Ponce de León and James Cook resulted in the exploration and discovery of vast areas of North and South America, Africa, Asia and islands of the Pacific Ocean.

Discovering New Lands

Among the early settlers to the “new world” of North America were the Pilgrims who established a colony in present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts. Following a treacherous 66-day voyage across the Atlantic Ocean aboard the Mayflower in 1620, the pioneers arrived to begin a new life.

William Bradford, who served as the Plymouth Colony’s governor, echoed Columbus’ statement.

“All great and honorable actions are accompanied with great difficulties, and both must be enterprised and overcome with answerable courage,” he said.

Almost 200 years later, the United States had been established as a nation, but exploration continued. Those who traveled into what is now Ohio or Tennessee were considered as venturing into the “wild frontier.”

Not long after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned a select group of U.S. Army volunteers under the command of Capt. Meriwether Lewis and his close friend 2nd Lt. William Clark. Their expedition began in May 1804 and was the first to cross what is now the western portion of the nation. Beginning near St. Louis on the Mississippi River, they made their way westward through the continental divide to the Pacific coast. Returning to their starting point in September 1806, Lewis and Clark established an American presence in previously unexplored territory.

Conquest of the Skies

By the turn of the 20th Century, most of the lands of the Earth had been explored and eyes began to turn to the skies.

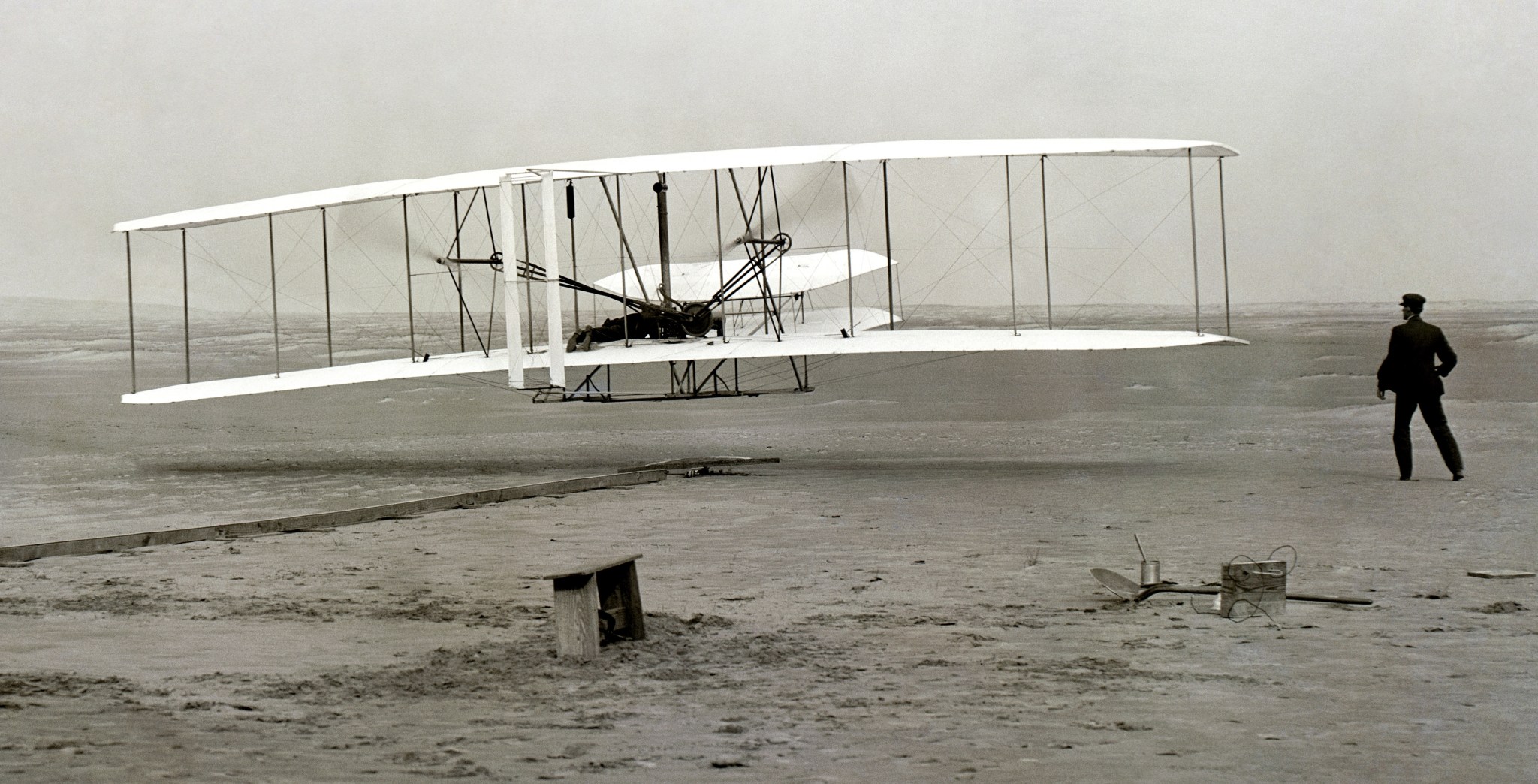

“The desire to fly is an idea handed down to us by our ancestors who traveled across trackless lands in prehistoric times,” said Orville Wright. “They looked enviously on the birds soaring freely through space, at full speed, above all obstacles on the infinite highway of the air.”

Together with his brother, Wilbur, the bicycle builders from Dayton, Ohio, designed the world’s first successful airplane. On Dec. 17, 1903, Orville made the first controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

While the age of aviation had begun, initially some thought it would have its limitations.

“No flying machine will ever fly from New York to Paris,” Orville Wright once said. “No known motor can run at the requisite speed for four days without stopping.”

As aircraft became larger, more powerful and more efficient, a new age of exploration began and proved there were few limitations to the new technology.

One of those prepared to prove this notion was a former U.S. Air Mail pilot named Charles Lindbergh. On May 20 and 21, 1927, he flew a small, single engine aircraft from Roosevelt Field in New York to Le Bourget Airport in Paris.

A trait that continues to define explorers is a willingness to accept the inherent hazards.

“I believe the risks I take are justified by the sheer love of the life I lead,” Lindbergh said.

The 1920s and 1930s were filled with news of aviation pioneers and explorers such as Richard Byrd, Amelia Earhart and Howard Hughes. During the World War II years, aircraft became larger, traveled farther, flew faster and climbed higher. Soon after, a new breed of explorer, known as test pilots “pushed the envelope” even farther –- again willing to accept the risks.

“You don’t concentrate on risks,” said U.S. Air Force pilot Chuck Yeager. “You concentrate on results. No risk is too great to prevent the necessary job from getting done.”

On Oct. 14, 1947, Yeager flew the X-1 rocket plane faster than the speed of sound –- over 700 mph — at Muroc Air Force Base, now Edwards Air Force Base, California. In doing so, he accomplished another feat once thought impossible.

Exploration of Space

By the late 1940s, a team of German-born rocket engineers and scientists were exploring beyond the skies into the edges of space, believing Goddard’s dream of a trip to Mars was achievable.

“I have learned to use the word ‘impossible’ with the greatest caution,” said Wernher von Braun who was leading what came to be known as the Rocket Team.

The history of exploration took the next logical step –- venturing into outer space. The new explorers of the 20th century embraced the sentiment of Russian space pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

“The Earth is the cradle of humanity,” he said, “but one cannot live in a cradle forever.”

On Oct. 3, 1957, scientists and engineers in the Soviet Union were the first to take a small step out of the “cradle” when they launched the world’s first satellite, Sputnik 1.

The United States orbited its first satellite, on Jan. 31, 1958. It was appropriately named “Explorer 1.” It was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida using a Redstone rocket developed by von Braun’s team.

A few weeks later, von Braun was interviewed by Time magazine about the possibility of humans traveling into space.

“Don’t tell me that man doesn’t belong out there,” he said. “Man belongs wherever he wants to go and he’ll do plenty well when he gets there.”

A Soviet was the first to get there in the spring of 1961.

Visionaries such as Robert Gilruth, who headed NASA’s Space Task Group at the Langley Research Center in Virginia, saw the achievement coming.

“I can recall watching the sunlight reflect off of Sputnik as it passed over my home on the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia,” he said. “It put a new sense of value and urgency on things we had been doing. I was sure that the Russians were planning for man in space.”

Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became that first person to travel in orbit on April 12, 1961.

A few weeks later, American astronaut Alan Shepard blasted into space atop one of von Braun’s Redstone rockets. He flew aboard a Mercury spacecraft designed by Gilruth’s team at Langley.

With humans showing they could “do plenty well” in space, President John Kennedy asked Americans to join in the boldest mission of exploration to date –- “landing a man on the moon and returning him safety to Earth.”

Kennedy spoke eloquently about space as an unexplored ocean to be navigated.

“We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people,” he said on Sept. 12, 1962, in a speech at Rice University in Houston. “But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal?”

In answering his own hypothetical question, Kennedy explained why we explore.

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard,” he said, “because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.”

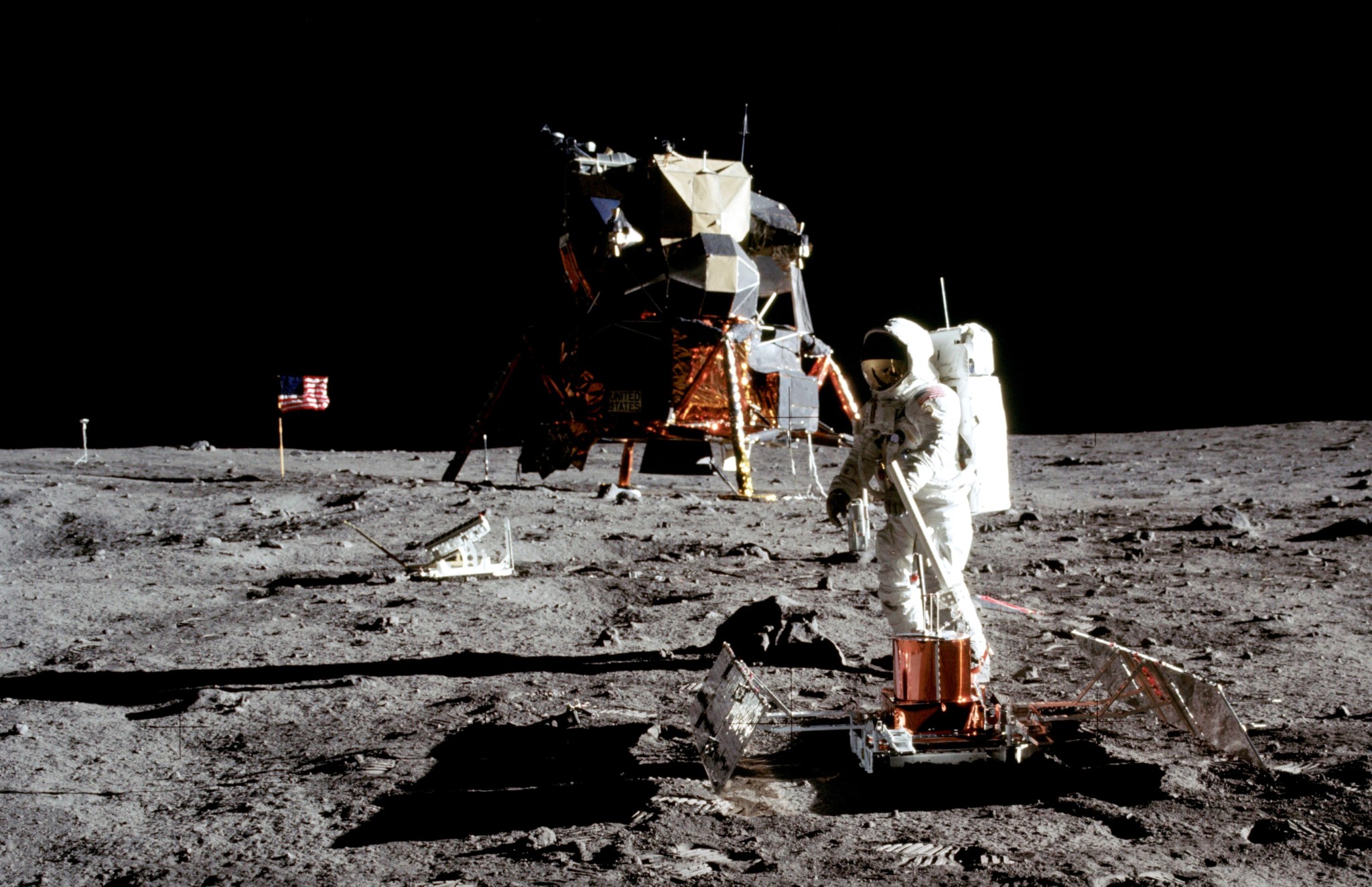

That goal was achieved on July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon’s Sea of Tranquility. Through December 1972, five more Apollo crews landed on the lunar surface, exploring and returning to Earth.

In 1992, then NASA Administrator Dan Goldin noted that the point of exploration isn’t just the destination, it’s the journey.

“It’s not about going someplace, it’s about what you find along the way,” he said. “Walk into any hospital and look at the technology. CAT scans, magnetic resonance, intensive care monitoring equipment — all derivatives of Apollo. No wonder Newsweek called Apollo ‘the best return on investment since Leonardo da Vinci bought himself a sketch pad.’”

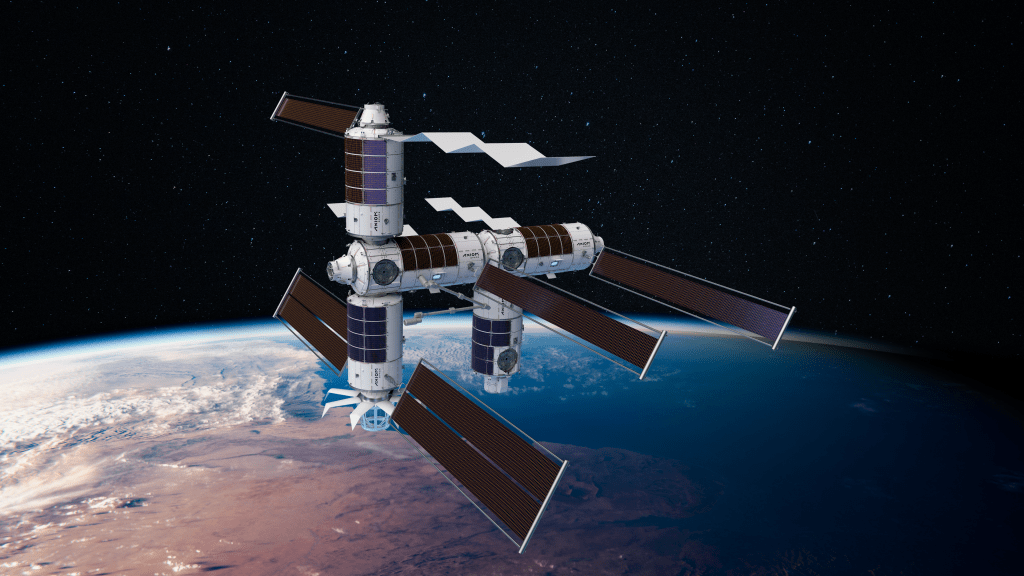

During three decades, NASA’s Space Shuttle Program flew 135 missions to not only utilize the benefits of microgravity in Earth orbit, but to learn how to live and work in space. The continuing legacy of the shuttle is the International Space Station where astronauts from around the world are learning what we need to know for the next giant leap -– an expedition to the Red Planet.

As President Barak Obama spoke on space exploration in the 21st century in an address at Kennedy on April 15, 2010, he called for another exploration challenge. This time, the mission is to embark on a 58-million-mile trip almost losing site of the shores of Earth.

“By the mid-2030s, I believe we can send humans to orbit Mars and return them safely to Earth,” he said. “And a landing on Mars will follow.”

NASA’s Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System rocket now are being built to achieve that goal to expand human presence in deep space and enable exploration of new destinations in the solar system.

At the Humans to Mars Summit on May 5, 2015, NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden explained America’s reasons for the journey. He noted that by looking back, we look forward.

“Because what we learn about the Red Planet may tell us more about our own home planet’s history and future,” he said, “and because it might just help us unravel the age-old mystery about whether life exists beyond Earth … Mars matters.”

The primary objective is the one envisioned by Robert Goddard as he looked into the sky during his youth and envisioned a trip to Mars. As Goldin noted, the journey will be worth the effort.

“Every time America has gone to the frontier, we’ve brought back more than we could ever imagine,” he said. “As NASA turns dreams into realities, and makes science fiction into fact, it gives America reason to hope our future will be forever brighter than our past.”