The first three articles in this mini-series described the near disastrous launch of the Skylab space station and the tireless efforts of NASA and contractor personnel to save the program. The end of the mission couldn’t have been more different from the beginning. When the Skylab 2 crew of Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, Pilot Paul J. Weitz, and Science Pilot Joseph P. Kerwin launched to the Skylab space station on May 25, 1973, it wasn’t certain that they could finish their planned 28-day mission. Eleven days earlier, Skylab suffered significant damage during its launch, leaving it overheated and under-powered after its meteoroid and thermal shield tore off, leaving one of its main solar arrays jammed closed and the other missing entirely. In the 10 days between the two launches, NASA and contractor personnel at Johnson Space Center (JSC), Marshall Space Flight Center and Kennedy Space Center designed, built and stowed in the Command Module a custom-designed parasol that the crew deployed on their second day in orbit to cool the station. And on June 7, Conrad and Kerwin conducted a record-breaking spacewalk to free the jammed solar array, giving Skylab enough power for them to complete their mission and save the program.

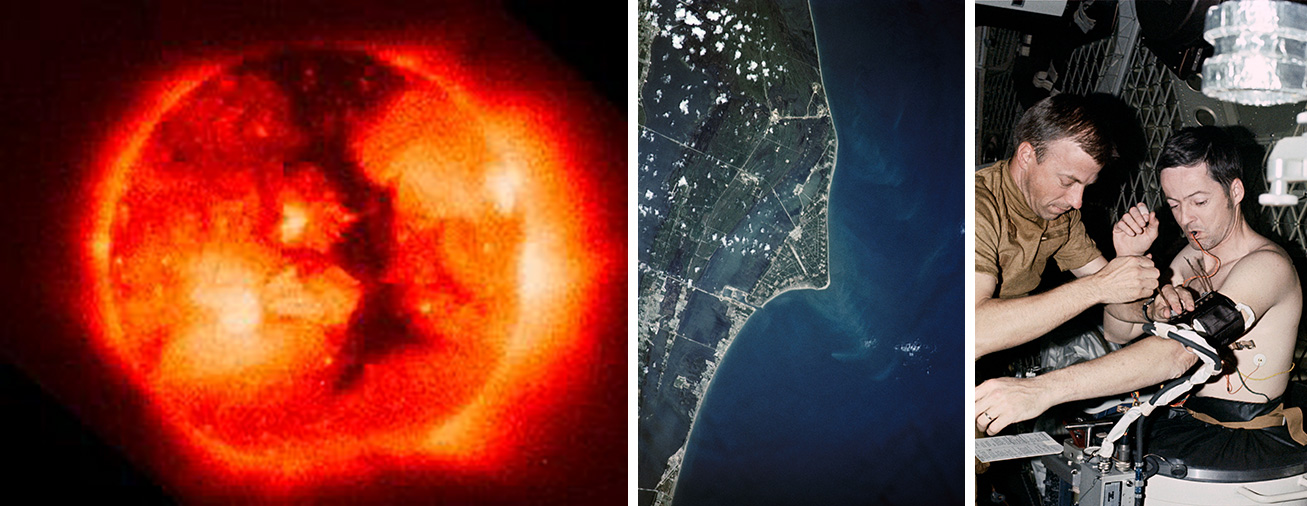

During the second half of their mission, Conrad, Weitz and Kerwin focused on completing as much science as possible, research being the primary goal of Skylab. Despite the slow start, by the end of the mission the crew completed 81% of the planned solar observations using the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM), 88% of the Earth observations using the Earth Resources Experiment Package, and more than 90% of the medical experiments. The results of the latter indicated that the crew overall remained healthy during their month-long stay in space, but all three lost weight and especially muscle mass. Based on that information, flight doctors increased the caloric intake and amount of exercise for the next Skylab crew.

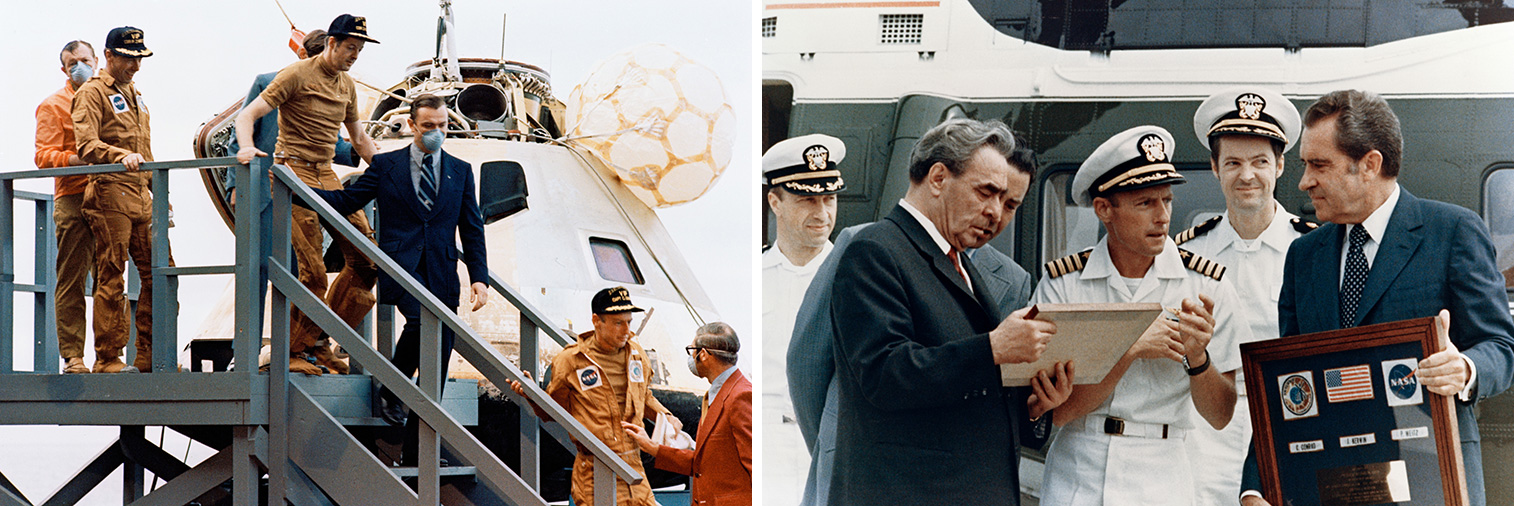

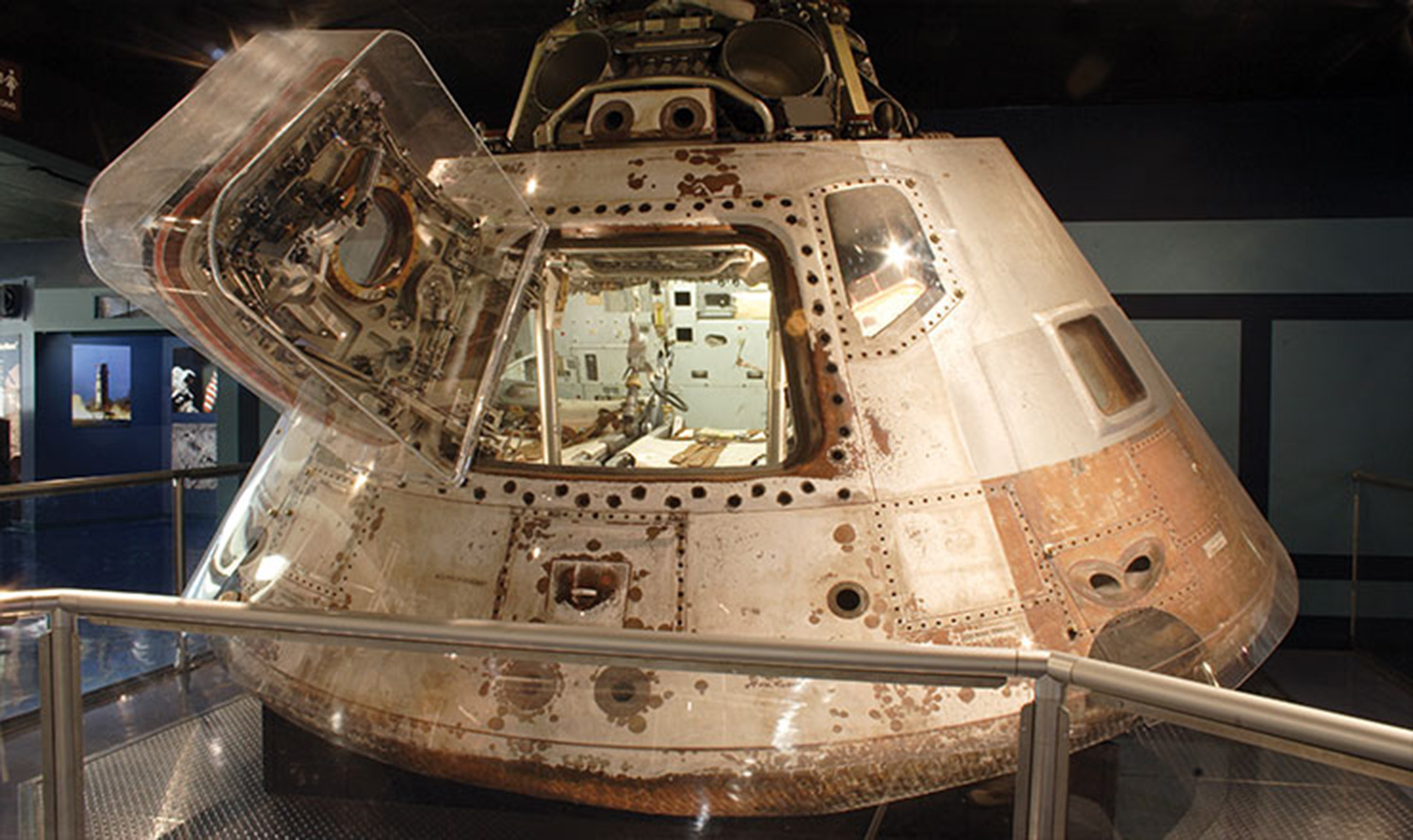

On June 18, the Skylab 2 crew broke the 24-day endurance record set by the Soviet Soyuz 11 crew in 1971. Two days later, Conrad and Weitz completed a 1-hour 36-minute spacewalk to retrieve film canisters from the ATM for return to Earth and replace them with fresh ones. Over the next two days, they prepared Skylab for an unmanned period until the second crew arrived in July. On June 22, after undocking from Skylab and photographing it during a fly-around inspection, they fired the Service Module’s engine to bring them home, after completing 404 orbits around the Earth. The Command Module (CM) splashed down about 800 miles southwest of San Diego and 6.5 miles from the prime recovery ship, the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga. Conrad, Weitz and Kerwin were the new record holders for the longest human space flight, 28 days and 50 minutes. Navy personnel lifted the CM onto the carrier, and the three crewmen emerged from the capsule, a little unsteady but able to walk unassisted. Although the spaceflight was over, the scientific mission went on, as the crew continued to be subjects for the medical experiments, first conducted in the Skylab Mobile Laboratory aboard the Ticonderoga and later back at JSC in Houston. The experiments tracked the crewmembers’ readaptation to a terrestrial environment.

An unexpected side trip occurred shortly after their return to Earth. President Richard M. Nixon invited the crew to the Western White House in San Clemente, California, where he was holding a summit with Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev. Two days after splashdown, as Ticonderoga sailed into San Diego, a helicopter carried the crew and their flight surgeon to meet with the two world leaders. The astronauts brought gifts of flags and patches flown in space, hurriedly mounted in shadow boxes by personnel on the aircraft carrier. To the flight surgeon’s horror, the crew broke with medical protocols by removing the surgical masks they wore to prevent any infections when they met Nixon and Brezhnev. The meeting over, the helicopter ferried them back to the carrier, and the next day a transport plane flew them home to Houston for reunions with their families. And more medical tests.

Read Astronauts Paul Weitz’s and Joe Kerwin’s oral histories.