By Jim Cawley

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center

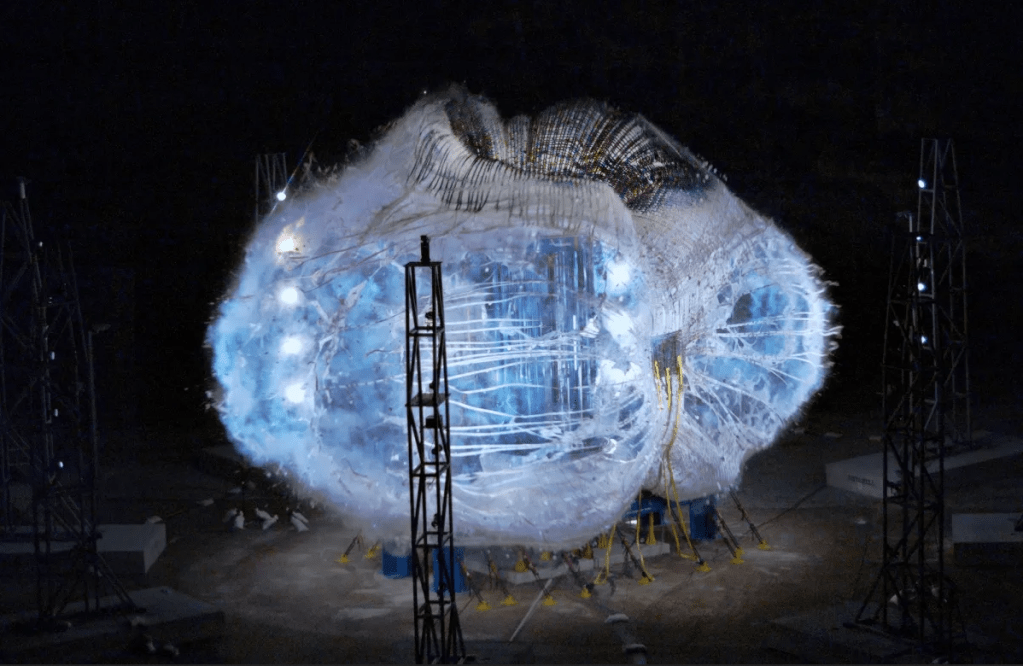

For Artemis missions, NASA’s Orion spacecraft will be traveling at 25,000 mph as it reenters the Earth’s atmosphere, which will slow it down to 325 mph. Parachutes will then bring it down to about 20 mph.

During the parachute deploy sequence, hardware will be jettisoned and fall into the Pacific Ocean below while the recovery ship awaits near the landing site. Keeping the ship and recovery team safe is critical to mission success.

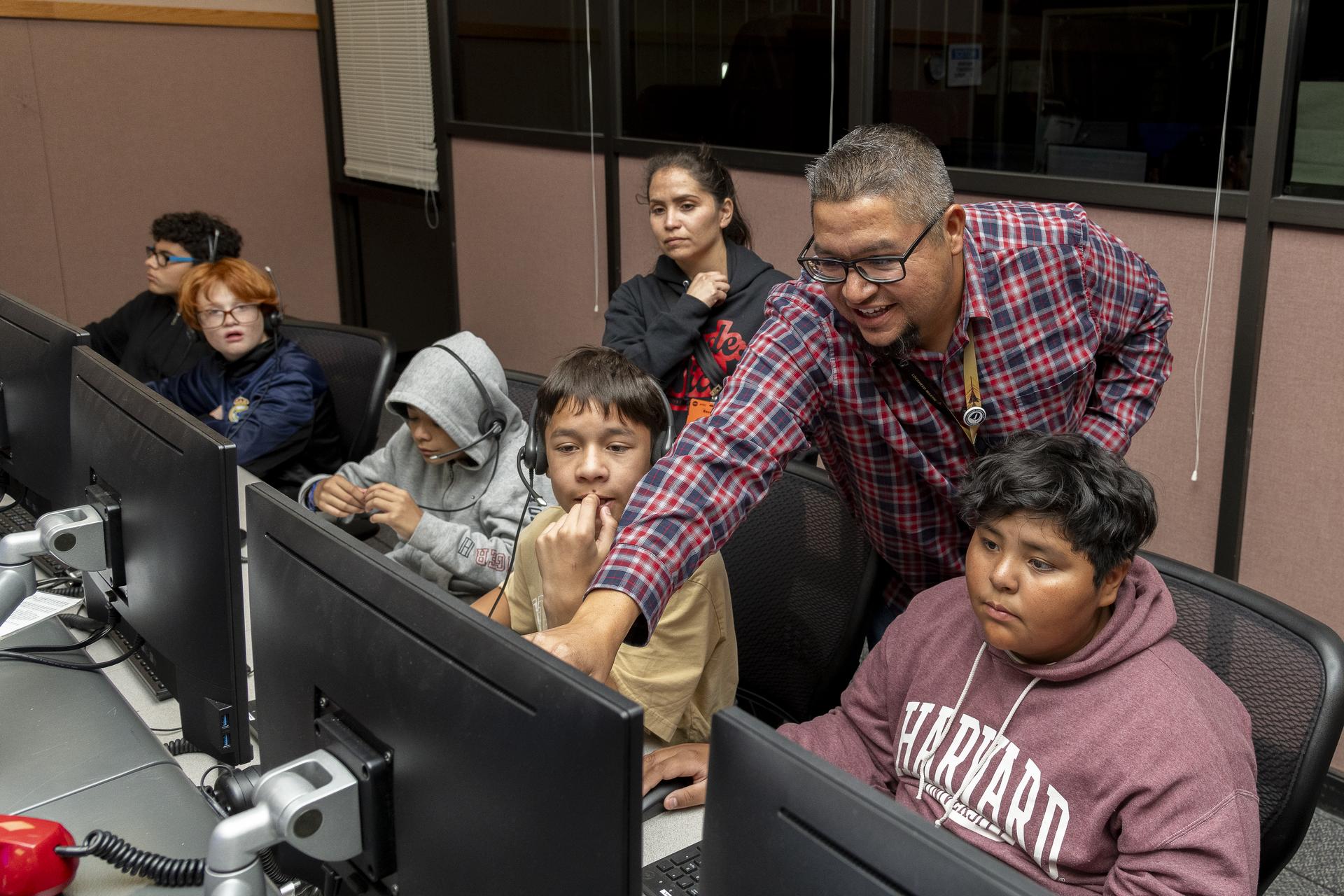

The Landing and Recovery team, led by Exploration Ground Systems at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, is prepared to safely recover Orion and attempt to recover the jettisoned hardware. A four-person team of engineers from NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston will also be onboard the U.S. Navy recovery ship with a “Sasquatch” — no, not an elusive hairy creature, but a very important software tool created specifically for Orion.

“Sasquatch is the software NASA uses to predict large footprints — that’s why we call it Sasquatch — of the various debris that is released from the capsule as it is reentering and coming through descent,” said Sarah Manning, a Sasquatch operator and aerospace engineer from the Engineering Directorate at Johnson.

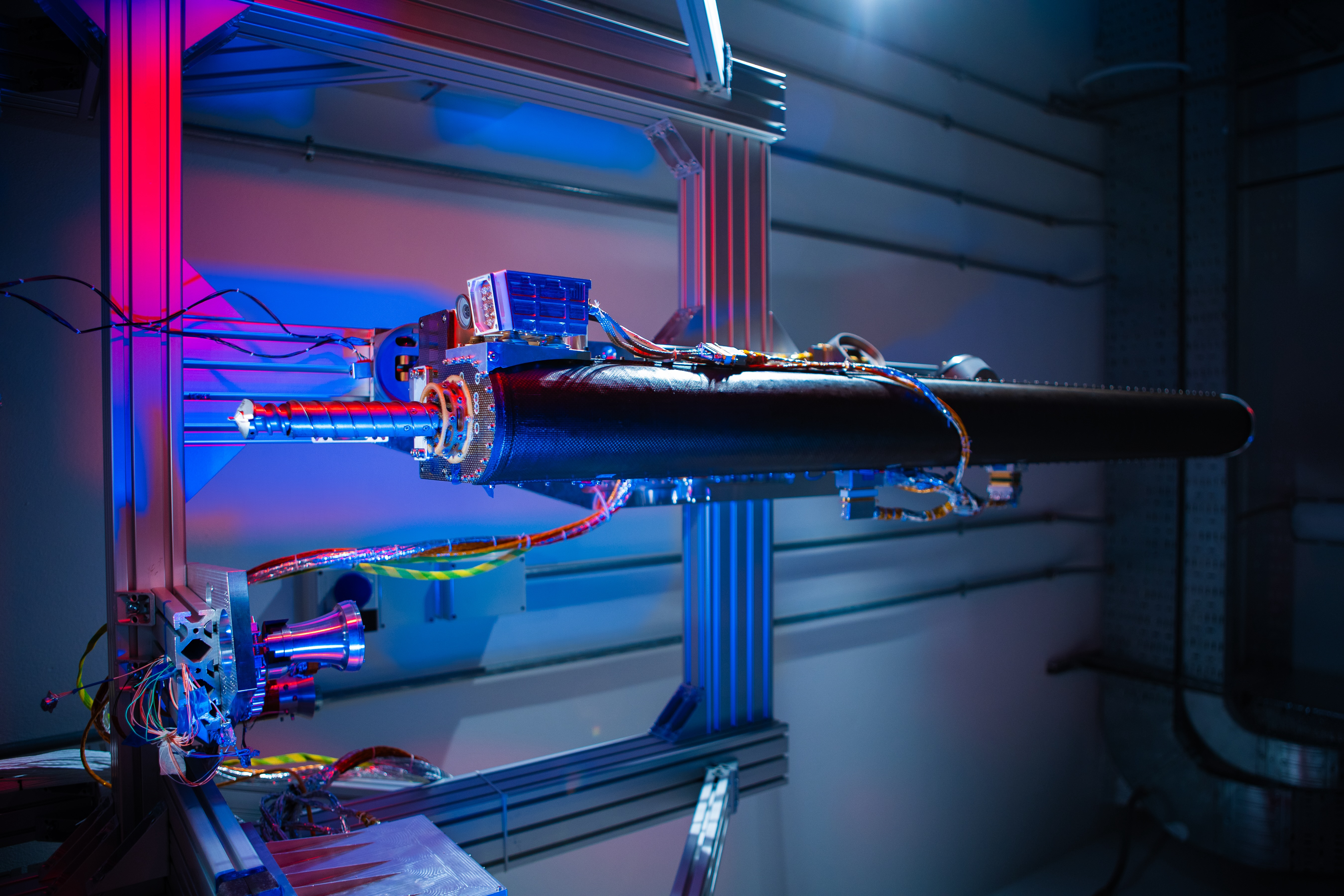

The hardware jettisoned, or released, during parachute deployment includes drogue and pilot parachutes that help initially slow and stabilize Orion, along with other elements necessary for the parachute sequence to deploy. The primary objective for the Sasquatch team is to help get the ship as close as possible to recover Orion quickly. A secondary objective is to recover as much hardware as possible.

Incorporating wind data gathered from the balloons with Sasquatch’s information about the debris, such as how quickly it falls, will show how the debris will spread based on the winds that day — scenarios the team has practiced for years in the Arizona desert where the Orion program conducted parachute testing. That’s where Sasquatch and eight weather balloons, released from the recovery ship by a team from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida and Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, come into play. They will use that information to position the recovery ship, small boats and helicopters outside the debris field to avoid injuries or damage.

“The upper-level wind speed and direction are critical in modeling the debris trajectories,” said Air Force Maj. Jeremy J. Hromsco, operations officer, 45th Weather Squadron at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. “Data provided to U.S. Navy and NASA forecast teams will allow them to accurately characterize and forecast the atmosphere during recovery operations.”

Positioning is paramount to recovering the hardware before it sinks. The team will first focus on recovering the capsule’s forward bay cover, a protective ring that covers the back shell of the capsule and protects the parachutes during most of the mission, as well as the three main parachutes. If they are successful, engineers can inspect the hardware and gather additional performance data.

About five days before splashdown, the Landing and Recovery team heads to a midway point between shore and where Orion is expected to land. As the spacecraft approaches, the Navy ship with the team continues its approach. How close they can get — and how quickly they can get to the capsule — depends on the work of the Sasquatch team.

“We have locations ready two hours before splashdown, but anything could change,” Manning said. “Then we have to make real-time decisions and people need to move.”

Helicopters that capture valuable imagery during descent and landing take off about an hour before splashdown. These aircraft set their flight plans based on the latest information from the Sasquatch team.

Artemis I will be an uncrewed flight test of NASA’s Orion spacecraft, Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, with the newly upgraded ground systems at Kennedy. During future Artemis missions, crew will be onboard. The recovery team intends to recover the crew and capsule within two hours of splashing down.

“Safety is absolutely very important,” Manning said. “We want to get as close as we can — far enough away that the recovery team is safe, but close enough that they can get there quickly.”