Correction: A prior version of this release indicated that the New Horizons observations were inconsistent with an earlier study that estimated there are 2 trillion galaxies in the universe. The New Horizons observations do not place a constraint on the total number of galaxies but rather do constrain the total amount of light all galaxies emit at ultraviolet and optical wavelengths.

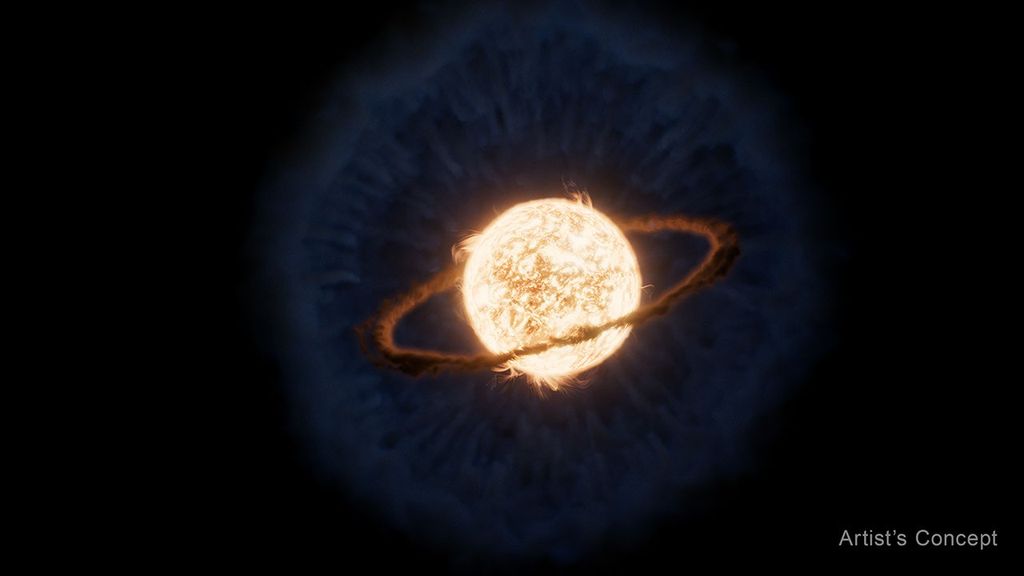

How dark does space get? If you get away from city lights and look up, the sky between the stars appears very dark indeed. Above the Earth’s atmosphere, outer space dims even further, fading to an inky pitch-black. And yet even there, space isn’t absolutely black. The universe has a suffused feeble glimmer from innumerable distant stars and galaxies.

New measurements of that weak background glow show that the unseen galaxies may be emitting more light than can be accounted for by existing surveys of the sky.

“It’s an important number to know – how many galaxies are there?” said Marc Postman of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, a lead author on the study.

An estimate of the total number of galaxies has been extrapolated from very deep sky observations by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and suggested there are about two trillion galaxies in the cosmos. It relied on mathematical models to estimate how many galaxies were too small and faint for Hubble to see. That team concluded that 90% of the galaxies in the universe were beyond Hubble’s ability to detect in visible light. That study also estimated the combined light from those two trillion galaxies. The new findings, which relied on measurements from NASA’s distant New Horizons mission, finds only about half as much light as that earlier Hubble study but still twice as much light as existing catalogs of observed galaxies can account for.

“Take all the light from galaxies Hubble can see, double that number, and that’s what we see – but nothing more,” said Tod Lauer of NSF’s NOIRLab, a lead author on the study.

These results were presented on Wednesday, Jan. 13th at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society, which is open to registered participants.

The cosmic optical background that the team sought to measure is the visible-light equivalent of the more well-known cosmic microwave background – the weak afterglow of the big bang itself, before stars ever existed.

“While the cosmic microwave background tells us about the first 450,000 years after the big bang, the cosmic optical background tells us something about the sum total of all the stars that have ever formed since then,” explained Postman. “It puts a constraint on the total starlight from galaxies that have been created, and where they might be in time.”

As powerful as Hubble is, the team couldn’t use it to make these observations. Although located in space, Hubble orbits Earth and still suffers from light pollution. The inner solar system is filled with tiny dust particles from disintegrated asteroids and comets. Sunlight reflects off those particles, creating a glow called the zodiacal light that can be observed even by skywatchers on the ground.

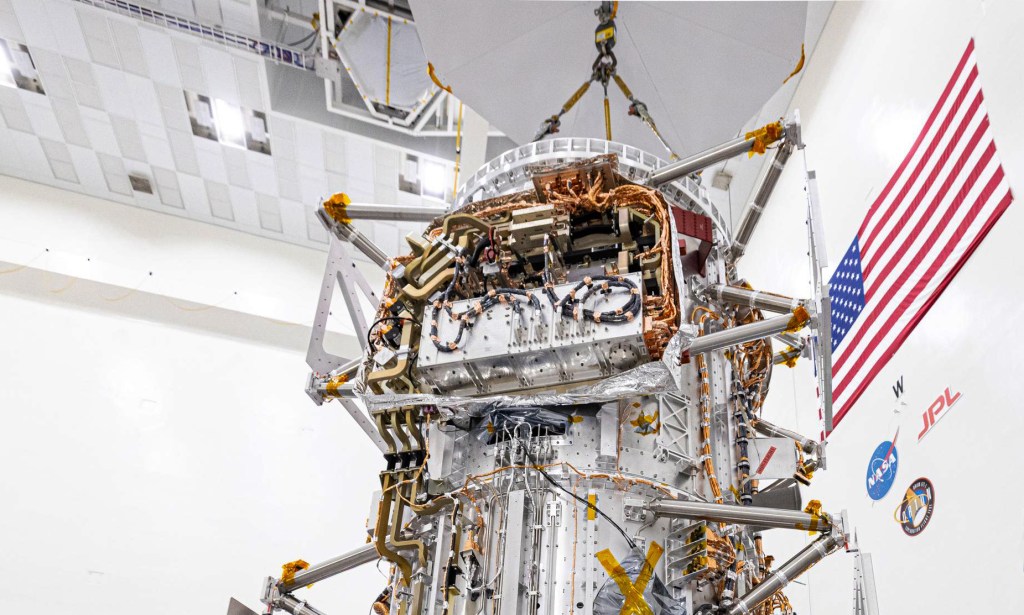

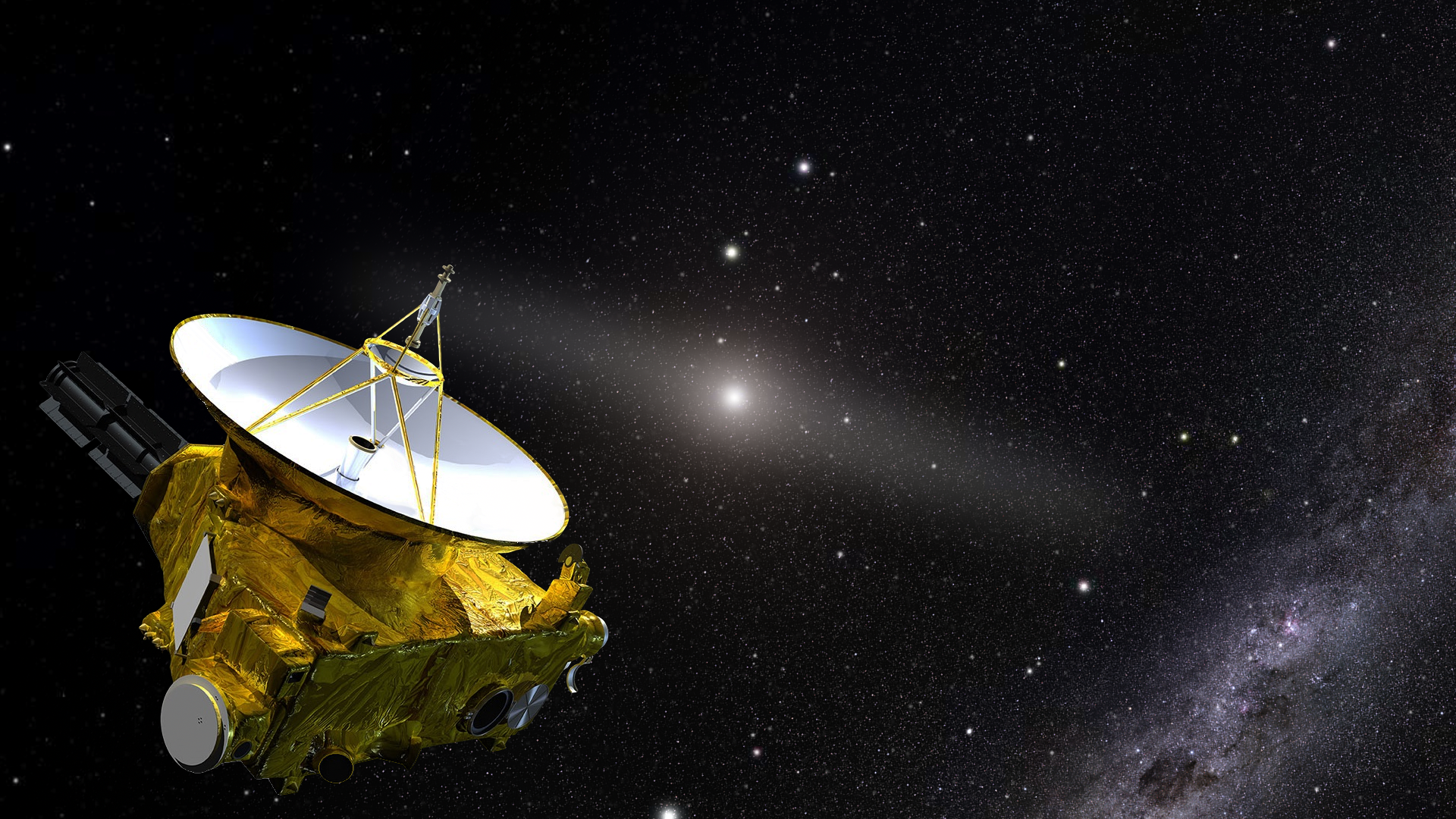

To escape the zodiacal light, the team had to use an observatory that has escaped the inner solar system. Fortunately, the New Horizons spacecraft, which has delivered the closest ever images of Pluto and the Kuiper Belt object Arrokoth, is far enough to make these measurements. At its distance (more than 4 billion miles away when these observations were taken), New Horizons experiences an ambient sky 10 times darker than the darkest sky accessible to Hubble.

“These kinds of measurements are exceedingly difficult. A lot of people have tried to do this for a long time,” said Lauer. “New Horizons provided us with a vantage point to measure the cosmic optical background better than anyone has been able to do it.”

The team analyzed existing images from the New Horizons archives. To tease out the feeble background glow, they had to correct for a number of other factors. For example, they subtracted the light from the galaxies expected to exist that are too faint to be identifiable. The most challenging correction was removing light from Milky Way stars that was reflected off interstellar dust and into the camera.

The remaining signal, though extremely faint, was still measurable. Postman compared it to living in a remote area far from city lights, lying in your bedroom at night with the curtains open. If a neighbor a mile down the road opened their refrigerator looking for a midnight snack, and the light from their refrigerator reflected off the bedroom walls, it would be as bright as the background New Horizons detected.

So, what could be the source of this leftover glow? It’s possible that an abundance of dwarf galaxies in the relatively nearby universe lie just beyond detectability. Or the diffuse halos of stars that surround galaxies might be brighter than expected. There might be a population of rogue, intergalactic stars spread throughout the cosmos. Perhaps most intriguing, there may be many more faint, distant galaxies than theories suggest. This would mean that the smooth distribution of galaxy sizes measured to date rises steeply just beyond the faintest systems we can see – just as there are many more pebbles on a beach than rocks.

NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope may be able to help solve the mystery. If faint, individual galaxies are the cause, then Webb ultra-deep field observations should be able to detect them.

This study is accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

Media Contact:

Christine Pulliam

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md.

410-338-4366

cpulliam@stsci.edu