Most distant object ever explored presents mysteries of its formation.

NASA’s New Horizons mission team has published the first profile of the farthest world ever explored, a planetary building block and Kuiper Belt object called 2014 MU69.

Analyzing just the first sets of data gathered during the New Horizons spacecraft’s New Year’s 2019 flyby of MU69 (nicknamed Ultima Thule) the mission team quickly discovered an object far more complex than expected. The team publishes the first peer-reviewed scientific results and interpretations – just four months after the flyby – in the May 17 issue of the journal Science.

In addition to being the farthest exploration of an object in history – four billion miles from Earth – the flyby of Ultima Thule was also the first investigation by any space mission of a well-preserved planetesimal, an ancient relic from the era of planet formation.

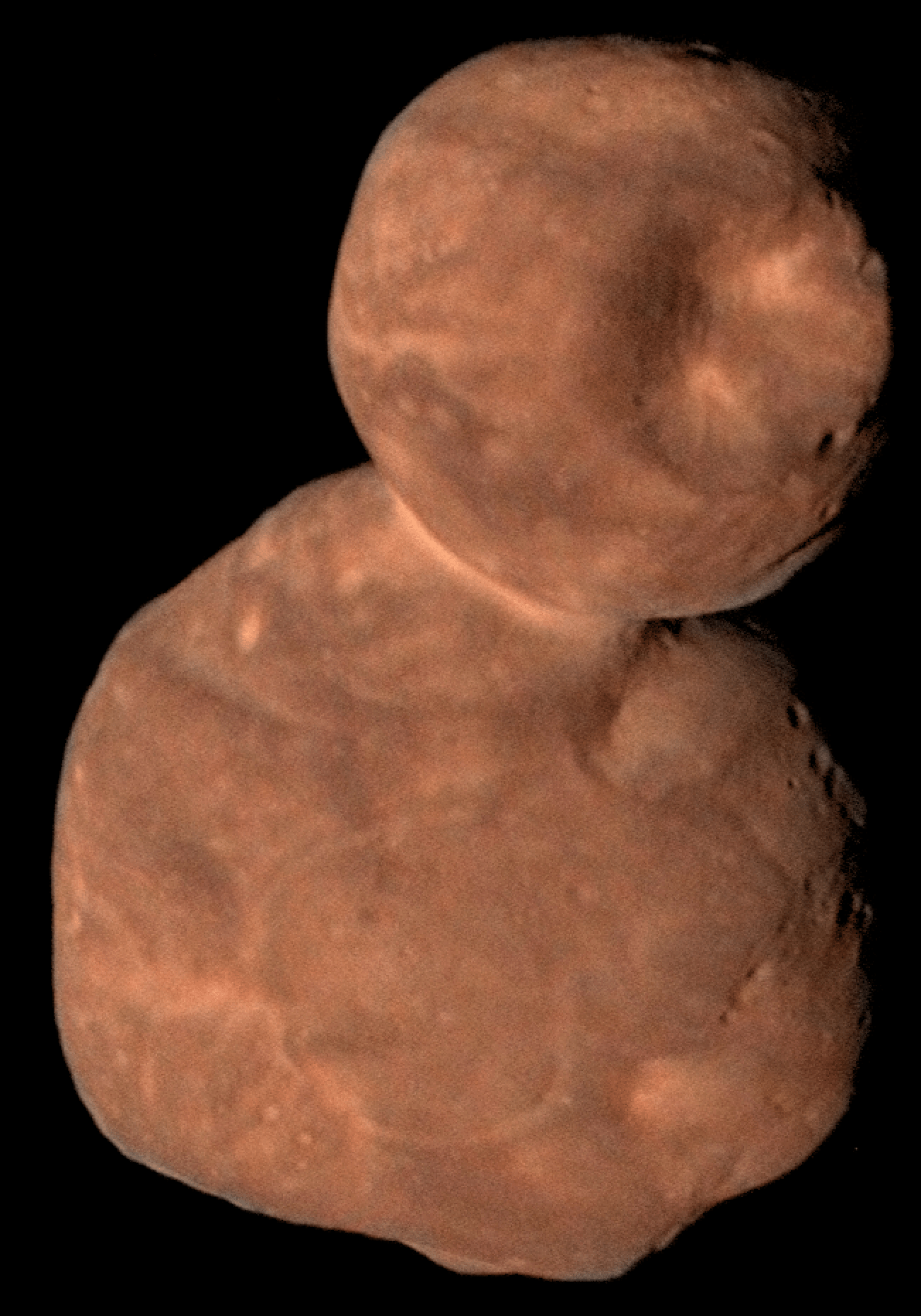

The initial data summarized in Science reveal much about the object’s development, geology and composition. It’s a contact binary, with two distinctly differently shaped lobes. At about 22 miles (36 kilometers) long, Ultima Thule consists of a large, strangely flat lobe (nicknamed “Ultima”) connected to a smaller, somewhat rounder lobe (nicknamed “Thule”), at a juncture nicknamed “the neck.” How the two lobes got their unusual shape is an unanticipated mystery that likely relates to how they formed billions of years ago.

The lobes likely once orbited each other, like many so-called binary worlds in the Kuiper Belt, until some process brought them together in what scientists have shown to be a “gentle” merger. For that to happen, much of the binary’s orbital momentum must have dissipated for the objects to come together, but scientists don’t yet know whether that was due to aerodynamic forces from gas in the ancient solar nebula, or if Ultima and Thule ejected other lobes that formed with them to dissipate energy and shrink their orbit. The alignment of the axes of Ultima and Thule indicates that before the merger the two lobes must have become tidally locked, meaning that the same sides always faced each other as they orbited around the same point.

“We’re looking into the well-preserved remnants of the ancient past,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado. “There is no doubt that the discoveries made about Ultima Thule are going to advance theories of solar system formation.”

As the Science paper reports, New Horizons researchers are also investigating a range of surface features on Ultima Thule, such as bright spots and patches, hills and troughs, and craters and pits on Ultima Thule. The largest depression is a 5-mile-wide (8-kilometer-wide) feature the team has nicknamed Maryland crater – which likely formed from an impact. Some smaller pits on the Kuiper Belt object, however, may have been created by material falling into underground spaces, or due to exotic ices going from a solid to a gas (called sublimation) and leaving pits in its place.

In color and composition, Ultima Thule resembles many other objects found in its area of the Kuiper Belt. It’s very red – redder even than much larger, 1,500-mile (2,400-kilometer) wide Pluto, which New Horizons explored at the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt in 2015 – and is in fact the reddest outer solar system object ever visited by spacecraft; its reddish hue is believed to be caused by modification of the organic materials on its surface New Horizons scientists found evidence for methanol, water ice, and organic molecules on Ultima Thule’s surface – a mixture very different from most icy objects explored previously by spacecraft.

Data transmission from the flyby continues, and will go on until the late summer 2020. In the meantime, New Horizons continues to carry out new observations of additional Kuiper Belt objects it passes in the distance. These additional KBOs are too distant to reveal discoveries like those on MU69, but the team can measure aspects such as the object’s brightness. New Horizons also continues to map the charged-particle radiation and dust environment in the Kuiper Belt.

The New Horizons spacecraft is now 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion kilometers) from Earth, operating normally and speeding deeper into the Kuiper Belt at nearly 33,000 miles (53,000 kilometers) per hour.

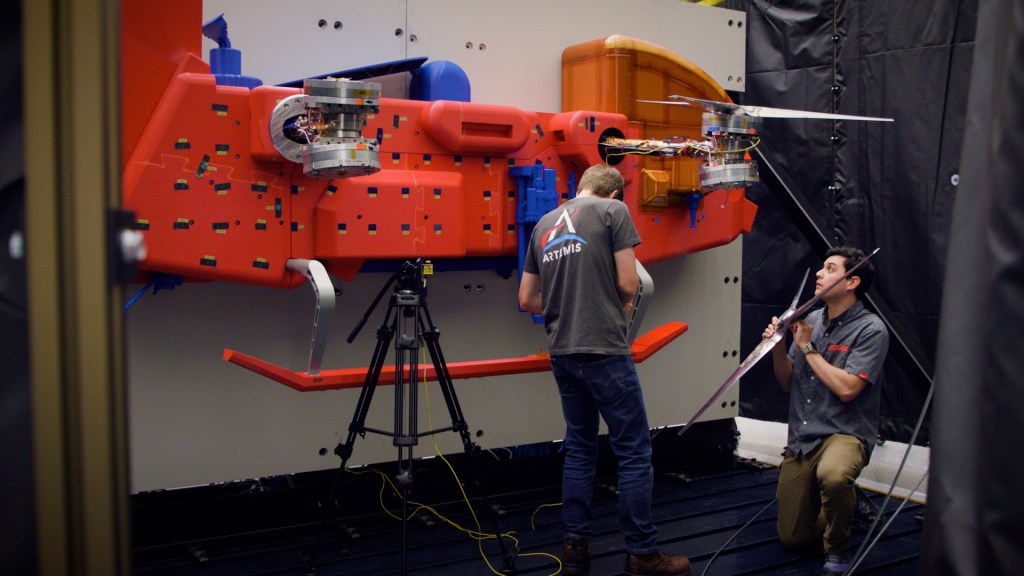

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, designed, built and operates the New Horizons spacecraft, and manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. The MSFC Planetary Management Office provides the NASA oversight for the New Horizons. Southwest Research Institute, based in San Antonio, directs the mission via Principal Investigator Stern, and leads the science team, payload operations and encounter science planning. New Horizons is part of the New Frontiers Program managed by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.