By Jim Cawley

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center

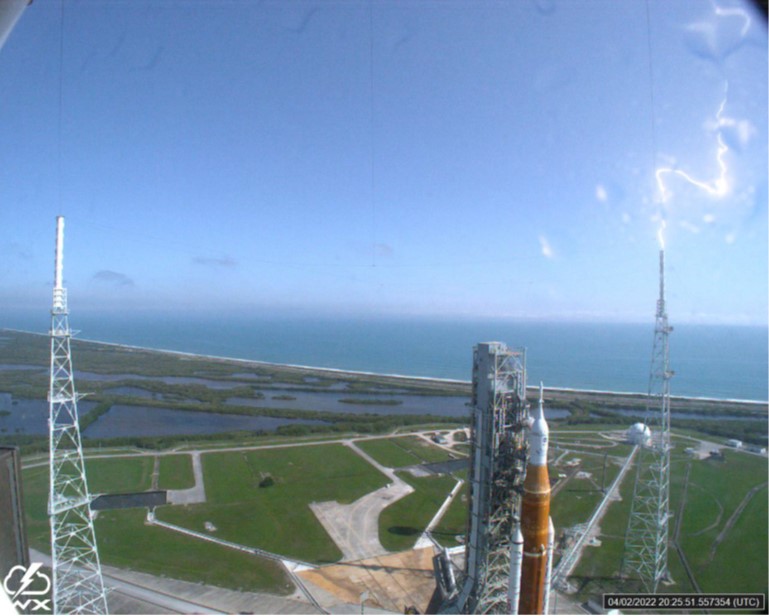

The most powerful lightning strike ever recorded at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center recently put the Florida spaceport’s lightning protection system at Launch Pad 39B to the test.

On April 2, the system’s high-speed cameras activated after picking up weather conducive to lightning in the area. NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) and Orion spacecraft were on the pad for a wet dress rehearsal attempt in preparation for the Artemis I launch, raising the stakes for the protection system’s role.

The storm produced lightning that struck inside the pad perimeter four times, including one which produced only the second positive lightning strike at pad 39B since the pad’s new lightning protection system was installed at Kennedy. Positive strikes, which transfer positive charges to the ground, are rare and account for less than 5 percent of all cloud-to-ground strikes. They typically send a more powerful surge of electricity to the ground, making them more dangerous than the more common negative strikes.

“There was a tremendous amount of energy that was transferred by this positive event,” said Dr. Carlos Mata, who designed the system for NASA under a contract and now is the chief technologist for Titusville, Florida company Scientific Lightning Solutions, which provides data analysis for lightning strikes at Kennedy when needed.

“After more than 30 milliseconds, we still had almost 3,000 amps flowing through the ground. This particular event falls into that tiny percentage – less than 1 percent – that you just don’t expect to happen.”

Amps, or amperes, are used to measure electricity. Ultra-high voltage transmission lines carry less than 3,000 amps to power up entire cities.

The first positive strike at Kennedy occurred in 2011, the first year the system was operational, though that one was significantly weaker and occurred outside the pad’s perimeter. The most recent event was intercepted by the lightning protection system, which transferred the lightning’s energy through catenary wires to the ground. It also was captured by the towers’ high-speed cameras, the launch pad’s transient recorders, the mobile launcher lightning instrumentation, and additional lightning instrumentation deployed to monitor the pad.

“I’ve never seen something so amazing,” said Jose Perez-Morales, Exploration Ground Systems senior project manager who was in charge of many of the upgrades to pad 39B to prepare it for new exploration launches after the Space Shuttle Program. “The strike occurs within milliseconds, but with the high-speed cameras, you can see frame by frame how it came from the ground and air. And when they met each other, that’s when you had the lightning strike.”

There was no damage to the rocket or spacecraft, despite the large electromagnetic field generated by the strike.

“You design things to withstand certain energy levels, but in this line of business, you can’t test it to make sure that it does what you expect it to do – you have to wait for Mother Nature to test it for you. And Mother Nature did put it to the test,” Mata said. “Once we started looking at the data and realized the system had done what we designed it to do, I don’t think that I can describe how I felt, knowing that we hadn’t let anyone down, that we did our due diligence, and we did it right.”

The system was one of the first things added to the upgraded pad to protect technicians. Since the system was activated, there has not been a lightning strike within the intended area of protection at pad 39B. Even the recent history-making flash of electrical energy couldn’t blemish that record.

Several years ago, while working on a contract as Kennedy’s Advanced Technology and Development Laboratory technical lead, Mata used software he designed to run simulations for a new lightning protection system at the pad. During design, he positioned the towers using this software and was able to obtain full coverage of the mobile launcher by using three lightning towers, rather than the single tower that was part of the previous pad infrastructure during the space shuttle era and only partially protected the orbiter.

“He did a tremendous amount of field work to ensure we had the most robust system while still saving a significant amount of money for NASA,” Perez-Morales said.

At nearly 600 feet, the taller towers are positioned to provide more protection to flight hardware. The height of the towers is a function of the height of the mobile launcher and the SLS rocket when at the pad.

Mata’s design is based on a rolling sphere theory. While the old system used during the Apollo and shuttle programs featured a 45-degree cone of protection, which left a portion of the hardware exposed, Mata’s design completely protects all hardware – including the mobile launcher – under catenary wires. Supported by long insulation masts at the top of the towers, the wires run to the ground almost diagonally, steering the lightning current away from the rocket.

Click here for more information on Launch Pad 39B. Click here for images of lightning strikes near the pad since the lightning protection system was installed.