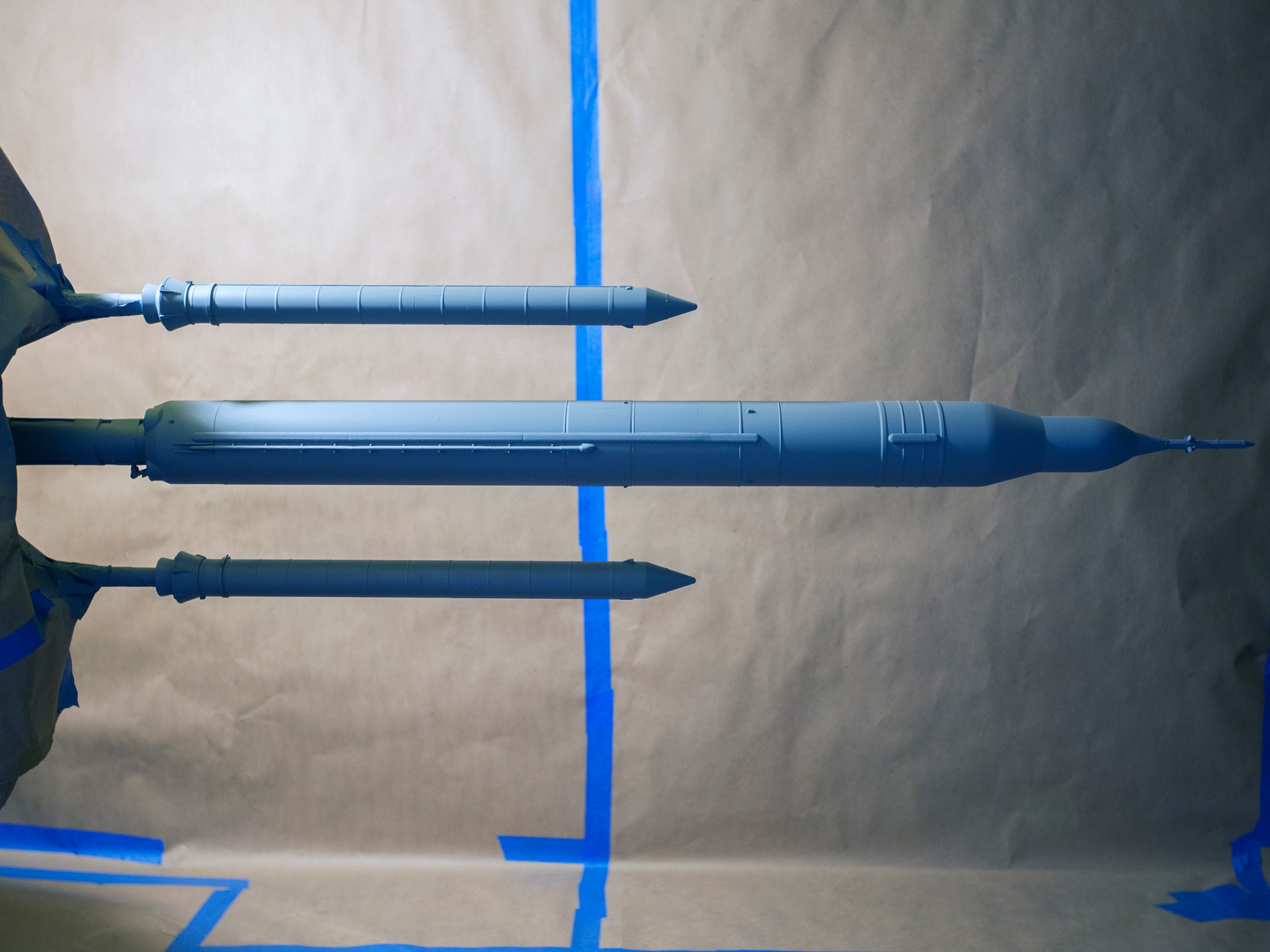

NASA’s most advanced launch vehicle is undergoing a variety of testing before the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket will be used to launch astronauts in the agency’s Orion spacecraft on missions to explore deep space. In one particular series of tests, this advanced piece of machinery is getting a fresh coat of paint.

At NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, a scaled model of the SLS is undergoing testing using pressure-sensitive paint to evaluate the separation of the left and right solid rocket boosters from the rocket’s core. The painted model undergoes testing at Mach 4 (3,069 mph or 4,939 km/h) for the Block 1B cargo and crew vehicle.

“This is an important aerodynamic test in assuring that the boosters will cleanly separate from the center core of the vehicle and not pose a hazard to mission success,” said David Piatak, acting co-lead for Langley’s SLS Aerodynamics Team.

“The aerodynamic data from the previous round of testing was very helpful to the larger SLS team in determining clearances for the booster separation of the first-generation rocket,” said Amber Favaregh, acting co-lead for Langley’s SLS Aerodynamics Team. “That information has helped shape decisions on booster separation timing in the trajectory.”

“We’re testing all the locations that the boosters could be at in relation to the core as they fall away,” said Courtney Winski, a researcher at Langley’s Configuration Aerodynamics Branch.

The solid rocket boosters on the side of the SLS act like extremely short stubby wings and can sometimes have surprising impacts on the system aerodynamics, Favaregh said.

Pressure-sensitive paint allows engineers to gain “a visual of the flow and pressure on the model during separation,” Winski said. “It gives us more data on how it is going to separate, and possible effects on flow path.”

A similar SLS model, also tested at Langley’s Unitary Plan Wind Tunnel, underwent testing for the Exploration Mission-1, which will be an uncrewed test flight. The rocket will send the Orion spacecraft on a mission travel thousands of miles beyond the Moon over the course of about three weeks.

Langley isn’t the only NASA center putting a SLS model through testing using pressure-sensitive paint, as NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley has done examinations using the paint.

This round of testing with the specialized paint job “uses high pressure air to simulate the exhaust plumes of SLS to allow us the opportunity to validate the very complicated flow fields being evaluated by computational fluid dynamics,” she said.

Computational fluid dynamics is a branch of fluid mechanics that relies on a supercomputer for numerical analysis and data structures to solve and analyze problems. Testing in wind tunnels helps to supplement and validate the data from the computations, and can also uncover unanticipated findings.

“You find new things all the time,” Winski said.

“This rocket must get up to 17,500 mph (28,163 km/h) to reach orbit and pass through the Earth’s thick lower atmosphere at transonic and low-supersonic speeds where aerodynamic forces play a large role in the structural design of the vehicle, in addition to keeping the pointy-end moving toward its orbital target,” Piatak said. “So we must perform a great deal of ground testing in wind tunnels to measure the aerodynamic forces on the vehicle as it plows through the atmosphere on its way to orbit.”

Even after the launch, engineers will continue to analyze more data received on the rocket’s actual performance during the real-world conditions of launch, outside of the wind tunnel.

“I’m positive it will be a surreal experience to watch our rocket successfully launch,” Favaregh said. “I imagine some joyful tears and a lot of celebration. All that excitement will be followed by the excitement to take all that flight data and implement it in future configurations and variants of the SLS to keep pushing the boundaries of space exploration.”

Eric Gillard

NASA Langley Research Center