You could say Oscar Avalos’ JPL career was a Christmas miracle.

As a young Mexican American immigrant, Avalos and his parents traveled back to Colima, Mexico, every December to spend the holidays in their hometown with family and friends. But a trip in 1980 proved life-altering.

Then a freshman at Manual Arts High School in South Los Angeles, Avalos had his heart set on becoming an auto mechanic and was immersed in auto shop class. Over Christmas, however, the annual family trip went a few days past his scheduled break, and when Avalos returned to school, spring semester of auto shop was full.

Next to the newly closed door was an open one — to the machine shop. The teacher, Mr. Cervantes, asked Avalos if he would like to join his class instead.

He wasn’t sure what machining involved, but “I needed a class and I heard you’d get to make little cannons for practice and fire them in class, so I said yes,” Avalos says with a laugh.

The class came with a perk: Mr. Cervantes was friends with the machine-shop lead at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, who invited him to bring his class for a tour. Over the next four years, Avalos toured JPL every year and fell in love with the Lab and its machine shop.

“I was fascinated. Compared to the machines we had in shop class, it was night and day,” Avalos says. “They were making real parts for space.”

By the time he toured JPL as a senior, Avalos was the top student in the machine shop, with a straight-A transcript. As graduation neared, Mr. Cervantes suggested he apply to JPL, but Avalos was incredulous.

“‘Why don’t you just write a letter and ask for a job?’” Avalos recalls his teacher asking him. “I thought, ‘No, I want to go to the Marines.’ My parents were poor and I knew how much they sacrificed for me. Going to the Marines meant they wouldn’t have to pay for anything anymore.”

Still, Avalos decided to give JPL a shot. He pecked out a letter on his typewriter, listed his high school machine shop’s phone number at the top of the page, and mailed it to JPL in April of 1983.

A few weeks later, Avalos and his friends ditched class to drive to Santa Monica and play beach volleyball for the morning. When he stopped by school later, Mr. Cervantes cornered him.

“He said, ‘Where have you been?’ and I told him, ‘I’ve been sick.’ And he said, ‘Sick? Look at your suntan!’” Avalos recalls with a laugh. “Turns out, he was looking for me because JPL called.”

Avalos wasted no time returning the call. Don Scheriff, the section manager at the time, answered. “He said, ‘Oscar, I read your letter and I want to hire you. When do you graduate?’” Avalos says. “I told him June 16. And he said, ‘OK, you’ll start June 20.’”

Made in America

JPL’s job offer was the American dream come true for Avalos, who immigrated to the U.S. with his parents in 1972 when he was 8 years old. At the time, Avalos didn’t speak any English and was terrified to find himself in a new country where nothing was familiar.

“Where I grew up in Mexico, we were on the outskirts of town. No car. The best luxury you had was a donkey,” he says. “I was so scared to be here.”

His first year in Los Angeles, Avalos was too frightened to go to school. He eventually enrolled in the third grade, where, he says, he “didn’t know how to do anything or any of the homework.”

But a kind, bilingual classmate took notice.

“There was a little girl who knew how much I was struggling,” Avalos recalls. “I don’t have any explanation as to why she wanted to help me but she did.”

A few months into the school year, his school counselor informed him that he would be assigned one teacher who would help him speak English and another teacher who would help him write in English. “She must have said something to her mom or to the principal,” Avalos says. “That little girl was my angel.”

Over time, Avalos began to thrive at school, and he and his parents did their best to make ends meet at home. His father worked at an animal rendering company, driving around to pick up dead animals at farms whose skins would be sold to Japan for leather goods; his mother worked as a seamstress; and Avalos took a job as dishwasher at a Louisiana seafood restaurant for $3.50 per hour, with plans to enlist after graduation.

With that phone call from JPL, Avalos threw in the towel. “When I got the JPL job, I quit that day,” he says. “The Marines went out the window, and my dishwasher days were done.”

New Kid to Seasoned Pro

Three days after crossing the stage to accept his high school diploma, Avalos walked across JPL’s West Lot to report for duty on his first day at the machine shop. He was so nervous, he arrived an hour early for his shift. Inside, he was greeted by a group of older men sitting in the middle of the shop with their coffee and cigarettes.

“Hey kid, is this your first day?” one of them asked.

Avalos nodded. He pulled up a chair, and they proceeded to give him a speech for the next hour on how to succeed at JPL.

“Those guys took me under their wing,” Avalos says. “They told me, ‘Do your best, make good parts and never lie. If you make a mistake, tell the truth and you’ll have a good career here.’”

Avalos started by cleaning machines and working in the tool crib. After three months, he enrolled in JPL’s apprentice program, a machine training course for new hires that required participants to pursue at least an associate’s degree part-time. For the next three years, Avalos worked from 7:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. at JPL, then went to night school at Los Angeles Trade Tech College four days a week from 6 to 10 p.m. The apprenticeship paired him with a seasoned JPL machinist who taught him everything about building machine parts, from welding to inspection. He completed the program in 1986 at age 21.

Those years of work and school were pivotal not only for his career but also for his home life: They helped him stay away from the backdrop of gang violence in his neighborhood.

“I grew up among gangs, killings and all of that in South Central L.A.,” he says. “One kid was killed in my backyard right in front of me.”

The violence eventually claimed the life of his younger brother in 1987 at the age of 19.

Avalos credits his opportunities at JPL with helping him avoid joining a gang or getting into drugs and alcohol.

“This job saved me from a lot of things,” he says. “It absolutely saved my life.”

No Shortcuts

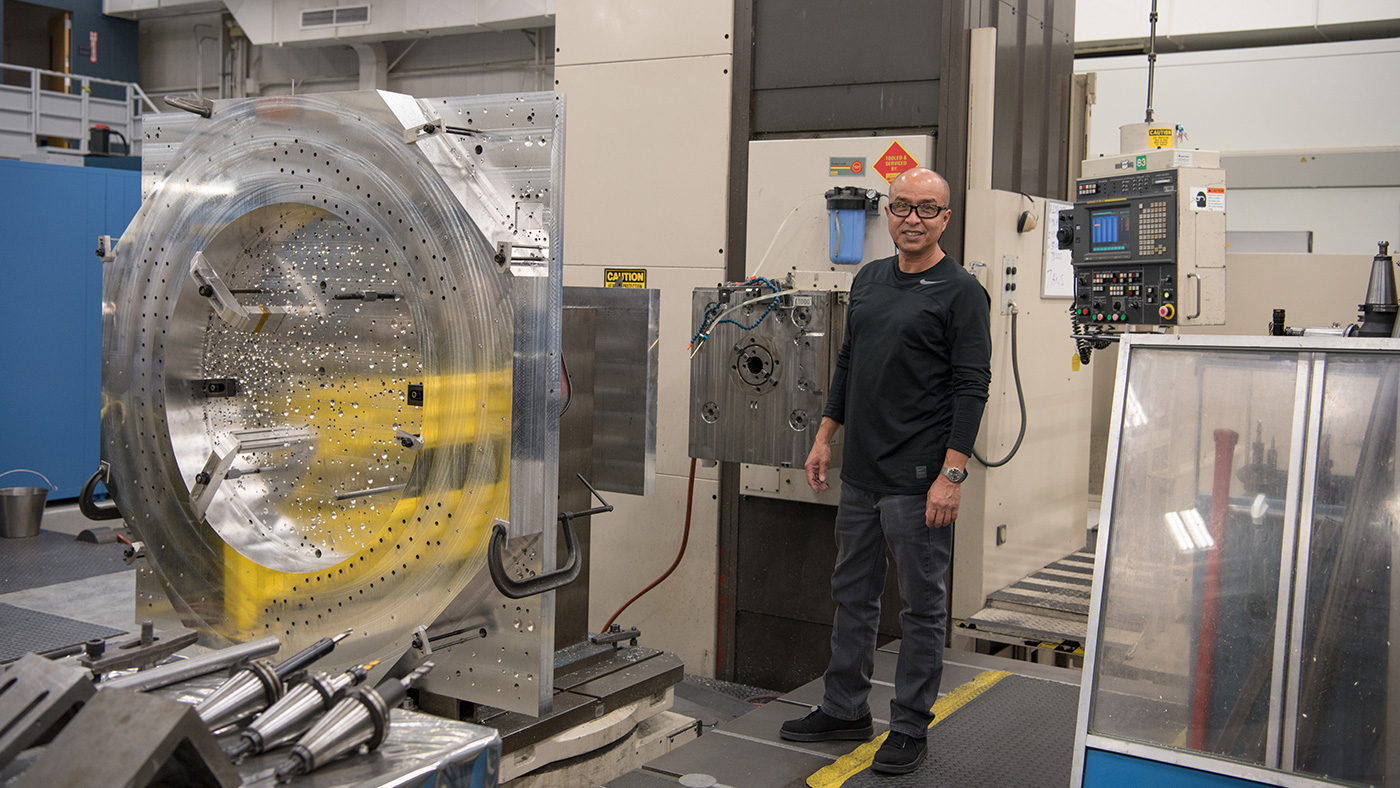

Some projects at JPL were so demanding, Avalos and his colleagues worked 16- to 18-hour days to meet their deadlines; he sometimes slept in his car in an alley on Lab. When asked to name the most complex part he’s ever built, Avalos points to the nine cameras on MISR, the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer, an instrument that studies Earth’s climate and environment.

“The dimensions had to be dead-on perfect and precise, and I said, ‘We can’t do that,’” Avalos recalls. “But I thought about it and thought about it and said, ‘OK, I’ll try this.’ We built a machine just to do that part. I had an inspector with me every single day for six months measuring the dimensions for the part.”

In the end, all nine cameras were successfully completed and installed on MISR, and his hard work paid off with compliments and advancement. The project engineer was so impressed with the performance of the cameras, she shared with others that “‘Oscar did the most perfect part I’ve ever seen,” he says.

Ten years into the job, Avalos was promoted to group lead of all the machinists in the shop, a role he’s held for 26 years now. His career has come with a number of highlights, from building parts for the tiny Sojourner rover of Mars Pathfinder to now working on parts for Mars 2020.

“It’s amazing, it’s like a dream,” Avalos says of seeing what he has built fly into space. “You had these parts in your hand, and when you get to see pictures on the news and see your parts in space, that’s rewarding.”

Paying It Forward

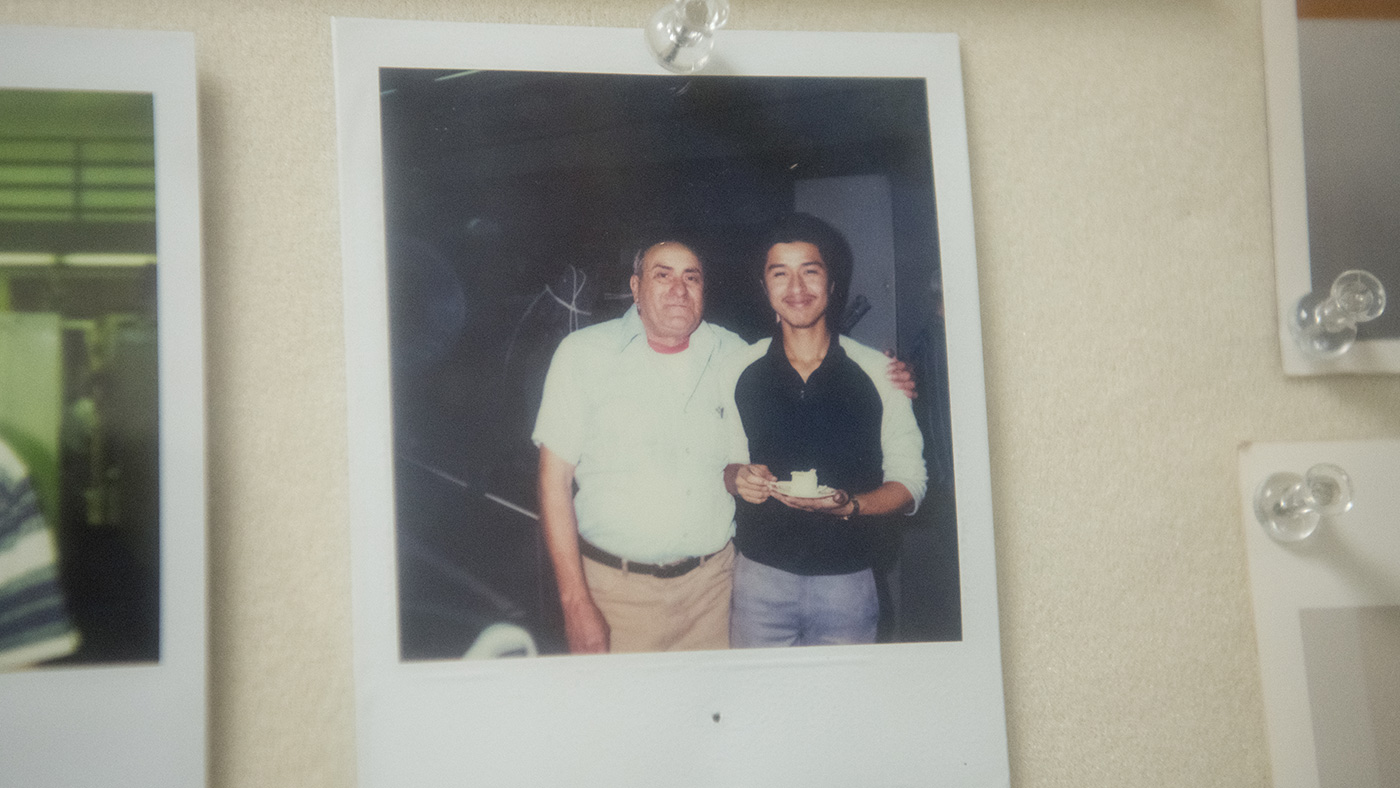

Avalos recognizes he wouldn’t be where he is without the support and encouragement of those around him, so he has his own way of giving back to the community: In addition to giving weekly and monthly tours, Avalos has worked every Explore JPL — formerly known as Open House — and Family Days event since the early 1980s, welcoming the thousands who come to JPL for a close-up experience of space exploration.

“You see the excitement that people have to see JPL, and you get to share that moment and show them what we do here,” Avalos says. “One year, I met a group from Ensenada, Mexico. They came here on buses. That’s how far our work goes.”

This year, Avalos will be showing parts the shop is making for Mars 2020, including the setup piece for the rover’s carousel, which holds the bits for the arm that will drill into the rock.

“It took us six months to build, it was so difficult,” Avalos says. “It’s exciting to show them that we start with a block of titanium that weighed close to 600 pounds and by the time you finish, it’s 18 pounds.”

To this day, though, the most rewarding experience for Avalos is still taking high school students on a tour through the machine shop once a month because he can see himself in the kids.

“It brings me back to when I was going on these tours,” he says. “I tell them to keep their grades up because it opens doors. And I tell my story because you never know — it could happen to them.”

Matthew Segal

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-8307

matthew.j.segal@jpl.nasa.gov

Written by Celeste Hoang

2019-091