An instrument on the spacecraft may have detected transient luminous events – bright flashes of light in the gas giant’s upper atmosphere.

New results from NASA’s Juno mission at Jupiter suggest that either “sprites” or “elves” could be dancing in the upper atmosphere of the solar system’s largest planet. It is the first time these bright, unpredictable and extremely brief flashes of light – formally known as transient luminous events, or TLE’s – have been observed on another world. The findings were published on Oct. 27, 2020, in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

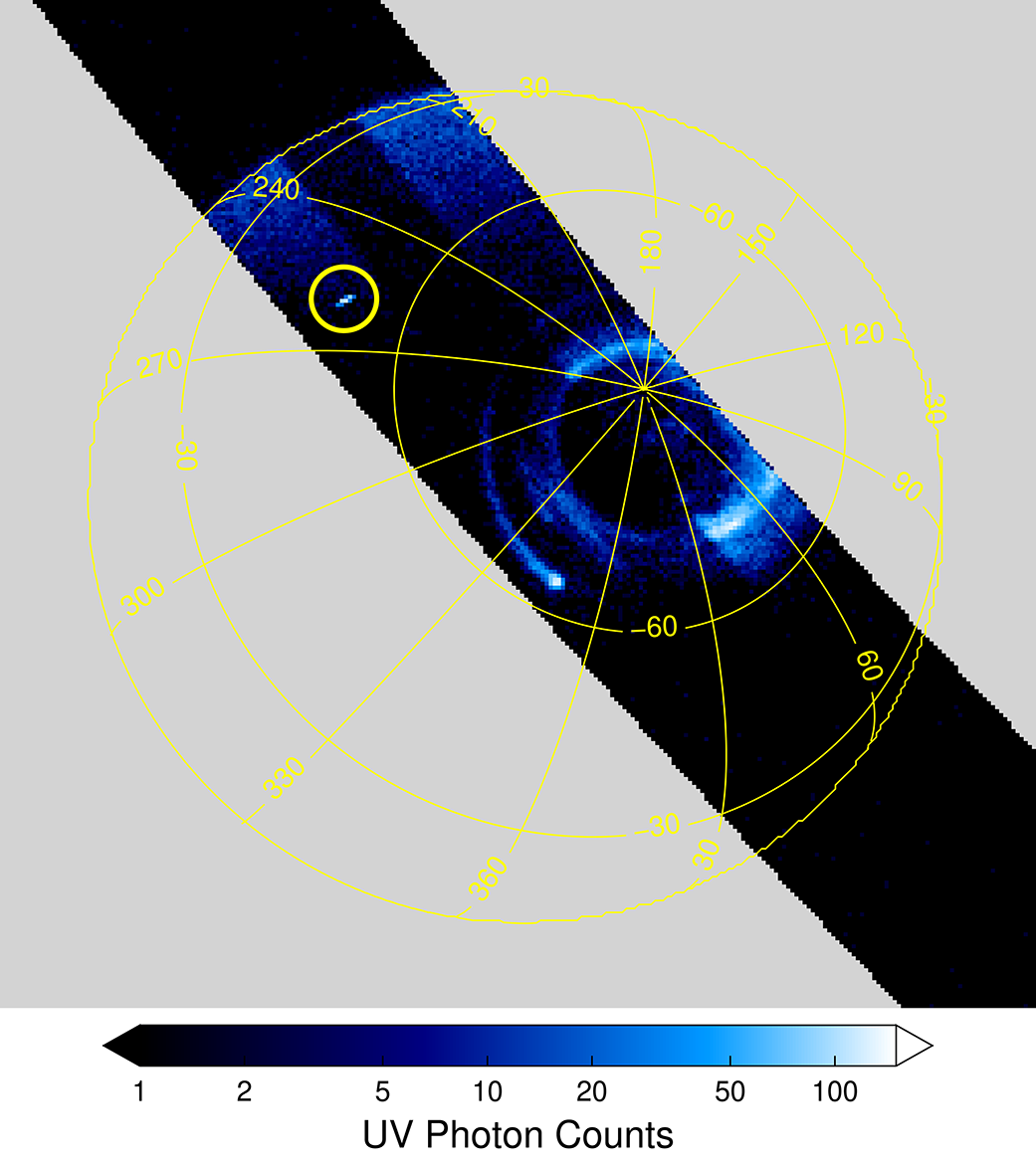

Scientists predicted these bright, superfast flashes of light should also be present in Jupiter’s immense roiling atmosphere, but their existence remained theoretical. Then, in the summer of 2019, researchers working with data from Juno’s ultraviolet spectrograph instrument (UVS) discovered something unexpected: a bright, narrow streak of ultraviolet emission that disappeared in a flash.

“UVS was designed to characterize Jupiter’s beautiful northern and southern lights,” said Giles, a Juno scientist and the lead author of the paper. “But we discovered UVS images that not only showed Jovian aurora, but also a bright flash of UV light over in the corner where it wasn’t supposed to be. The more our team looked into it, the more we realized Juno may have detected a TLE on Jupiter.”

Brief and Brilliant

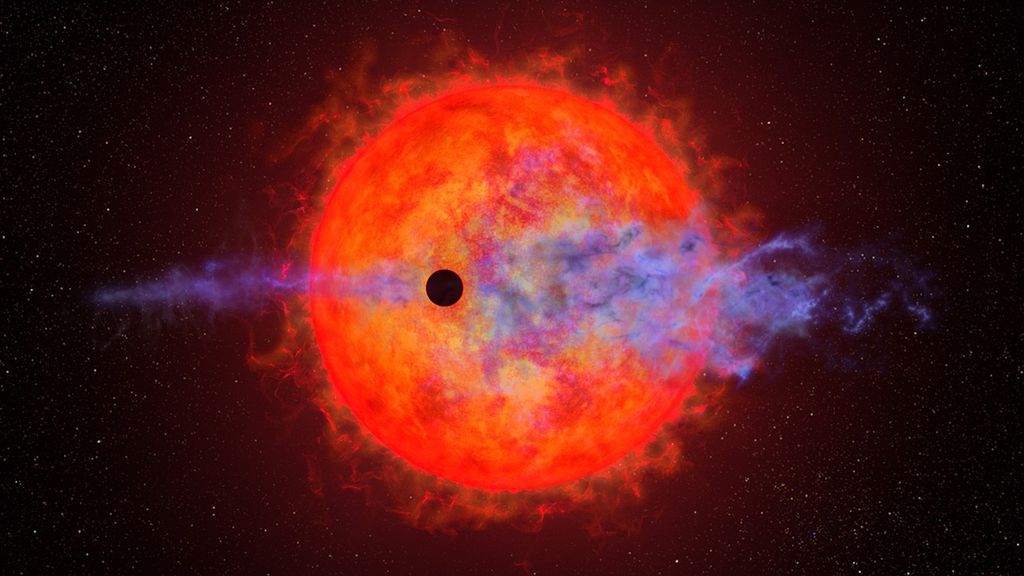

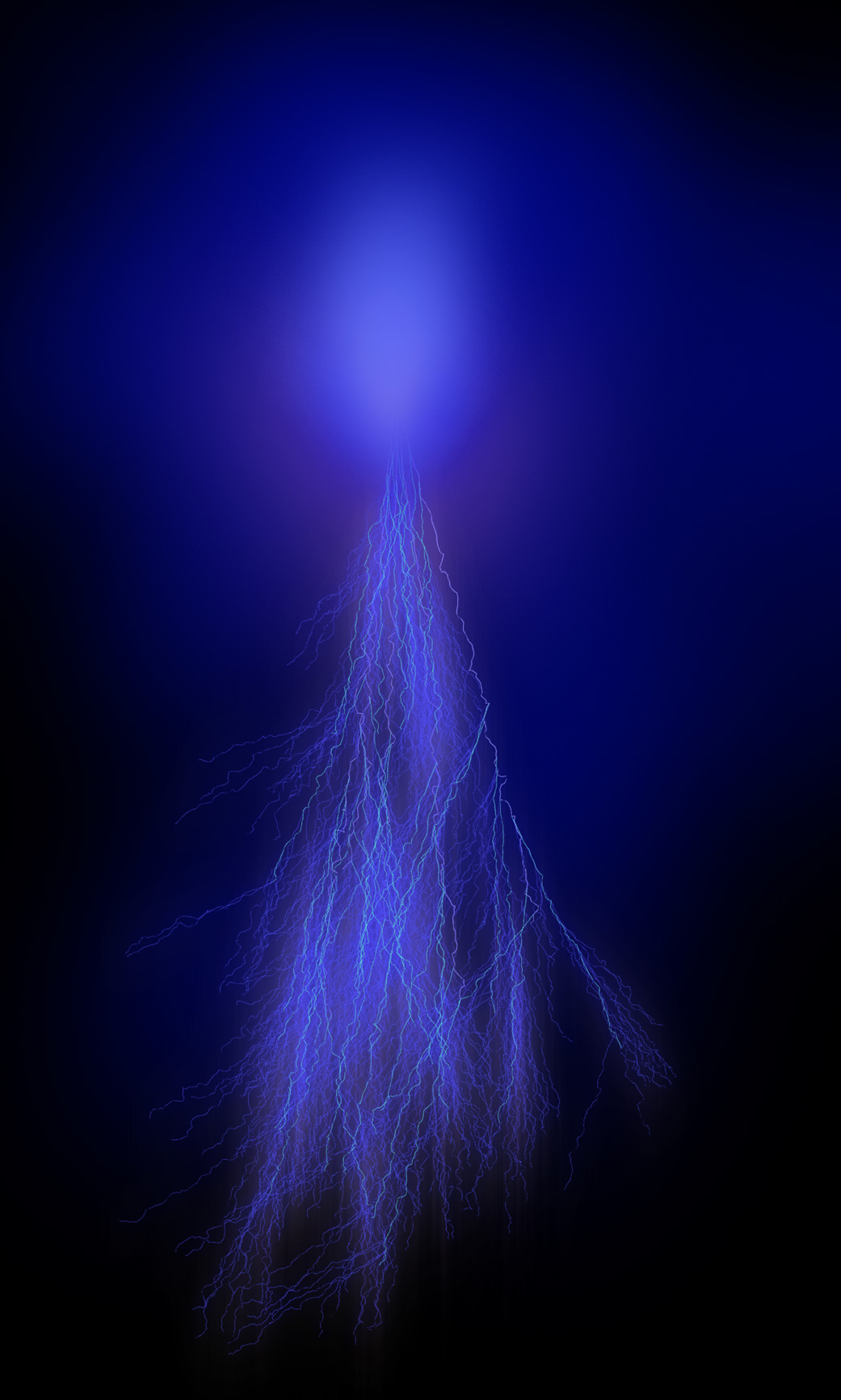

Named after a mischievous, quick-witted character in English folklore, sprites are transient luminous events triggered by lightning discharges from thunderstorms far below. On Earth, they occur up to 60 miles (97 kilometers) above intense, towering thunderstorms and brighten a region of the sky tens of miles across, yet last only a few milliseconds (a fraction of the time it takes you to blink an eye).

Almost resembling a jellyfish, sprites feature a central blob of light (on Earth, it’s 15 to 30 miles, or 24 to 48 kilometers, across), with long tendrils extending both down toward the ground and upward. Elves (short for Emission of Light and Very Low Frequency perturbations due to Electromagnetic Pulse Sources) appear as a flattened disk glowing in Earth’s upper atmosphere. They, too, brighten the sky for mere milliseconds but can grow larger than sprites – up to 200 miles (320 kilometers) across on Earth.

Their colors are distinctive as well. “On Earth, sprites and elves appear reddish in color due to their interaction with nitrogen in the upper atmosphere,” said Giles. “But on Jupiter, the upper atmosphere mostly consists of hydrogen, so they would likely appear either blue or pink.”

With three giant blades stretching out some 66 feet (20 meters) from its cylindrical, six-sided body, the Juno spacecraft is a dynamic engineering marvel, spinning to keep itself stable as it makes oval-shaped orbits around Jupiter. View the full interactive experience at Eyes on the Solar System. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Location, Location, Location

The occurrence of sprites and elves at Jupiter was predicted by several previously published studies. Synching with these predictions, the 11 large-scale bright events Juno’s UVS instrument has detected occurred in a region where lightning thunderstorms are known to form. Juno scientists could also rule out that these were simply mega-bolts of lightning because they were found about 186 miles (300 kilometers) above the altitude where the majority of Jupiter’s lightning forms – its water-cloud layer. And UVS recorded that the spectra of the bright flashes were dominated by hydrogen emissions.

A rotating, solar-powered spacecraft, Juno, arrived at Jupiter in 2016 after making a five-year journey. Since then, it has made 29 science flybys of the gas giant, each orbit taking 53 days.

“We’re continuing to look for more telltale signs of elves and sprites every time Juno does a science pass,” said Giles. “Now that we know what we are looking for, it will be easier to find them at Jupiter and on other planets. And comparing sprites and elves from Jupiter with those here on Earth will help us better understand electrical activity in planetary atmospheres.”

More About the Mission

JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft.

More information about Juno is available at:

https://www.missionjuno.swri.edu

Follow the mission on Facebook and Twitter at:

https://www.facebook.com/NASASolarSystem

https://www.twitter.com/NASASolarSystem

DC Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-9011

agle@jpl.nasa.gov

Alana Johnson

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-672-4780 / 202-358-0668

alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov

Deb Schmid

Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio

210-522-2254

dschmid@swri.org

2020-201