Teams are headed out by land, water, and air to collect data that will be used to forecast land gain and loss in the Mississippi River Delta as a result of sea level rise.

Around this time last year, scientists and researchers for Delta-X – NASA’s new investigation tasked with studying the Mississippi River Delta – were readying their boats and planes for their first field campaign in coastal Louisiana.

For the water-based part of the campaign, several boats were to be deployed to measure the flow of water through river channels and the subsequent transport of sediment across the region. For the airborne component, three planes outfitted with specialized remote sensing instruments were scheduled to fly over specific areas, taking measurements to estimate water and sediment flows and vegetation production.

Combined, the data were expected to provide key insights into the effect of sea level rise on the delta – specifically, why land is disappearing in some places and expanding in others.

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold around the world, those plans, like so many others, were put on hold – until now. The much-anticipated Delta-X spring field campaign is now underway.

“We are very excited to finally do this – to collect the datasets and see what they tell us,” said the project’s principal investigator, Marc Simard of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

Simard, like many on the Delta-X team, is coordinating with the field crews remotely – a big change from the original plan, which included sending a robust contingent of scientists, postdoctoral fellows, and students into the delta region of Louisiana. Other modifications to the original plan were also made out of an abundance of caution.

“For one thing, the teams collecting data in the field are working in three- to four-person pods,” Simard said. “They travel, work, and live together, and tasks have been coordinated so the pods don’t overlap with each other.”

This breaks down to one pod per boat and only essential personnel – pilots and radar operators, but no researchers – on the planes.

“Before, we were planning to be on the flights. I was looking forward to watching the data as it was coming in,” said Cathleen Jones, Delta-X deputy principal investigator at JPL. “Now we will get quick looks ahead of time but will need to wait until all the data are sent back from the field to really know what we’re looking at. Even so, we are all very excited for this campaign.”

How It Works

When a large river flows downstream toward the ocean or other body of water, it carries with it small particles of silt, sand, and clay. As it nears the ocean shore, this sediment sinks and accumulates to form a landmass called a delta. The river can also branch off to form smaller sediment-carrying channels of water on the way.

For this campaign, researchers are investigating the flow of water and sediment, vegetation growth, and other processes in two primary areas: the Atchafalaya Basin, which has been gaining land through sediment accumulation, and the Terrebonne Basin, which lies adjacent to the Atchafalaya and has been losing land rapidly.

Teams from Caltech, Louisiana State University, Florida International University, and other collaborating institutions are tasked with collecting important data by land, water, and air. Some are collecting water samples and other measurements by boat – data that will enable scientists to quantify the amount of sediment flowing through the channels that cut through the delta. Others are collecting vegetation samples to better understand the role plants play in elevating soil levels. And another team will take a closer look at where sediment is being deposited in the wetlands.

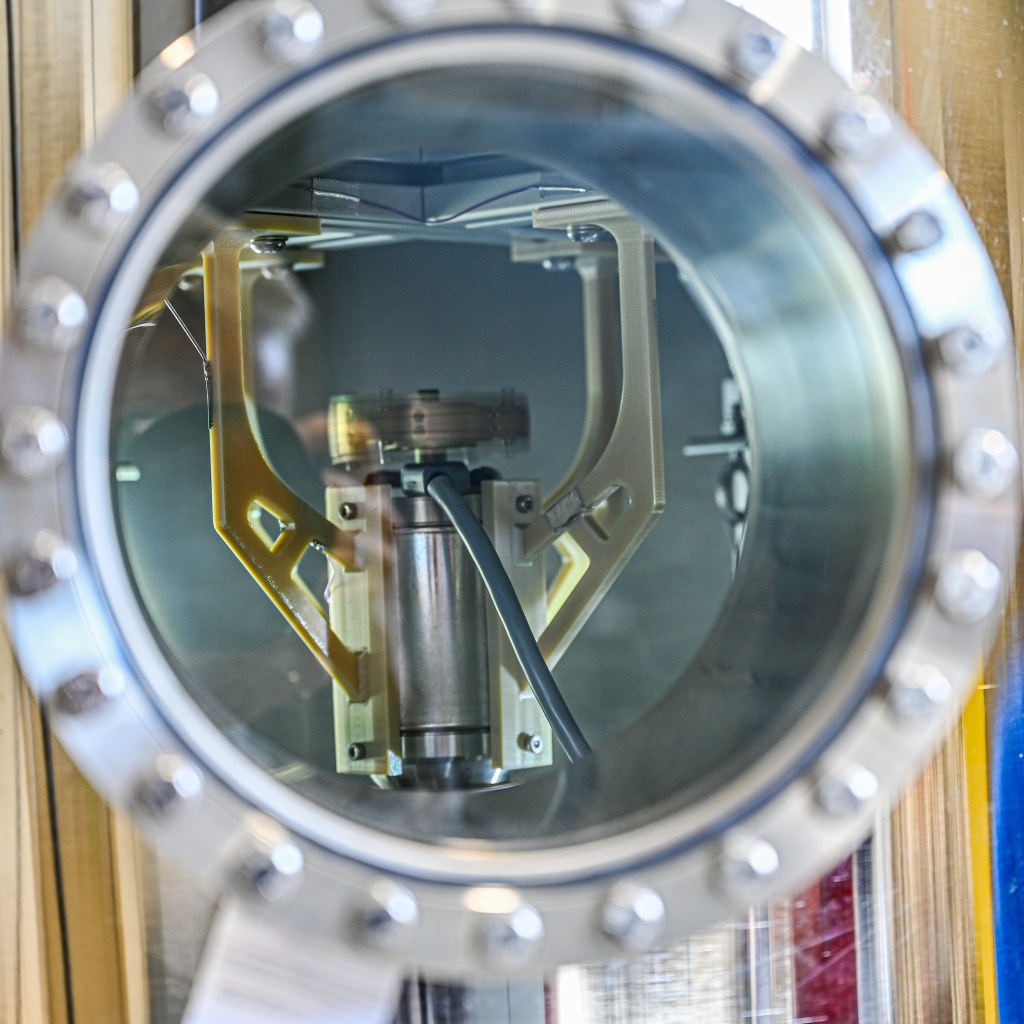

Separately, crews in three aircraft will fly over designated areas simultaneously to acquire data via specialized remote sensing instruments that will provide a complete landscape-level perspective. One plane, equipped with NASA’s AirSWOT instrument, will measure water-surface elevation and slope in the channels, rivers, and lakes that make up the delta region. This will help scientists estimate the volume of water flowing through channels.

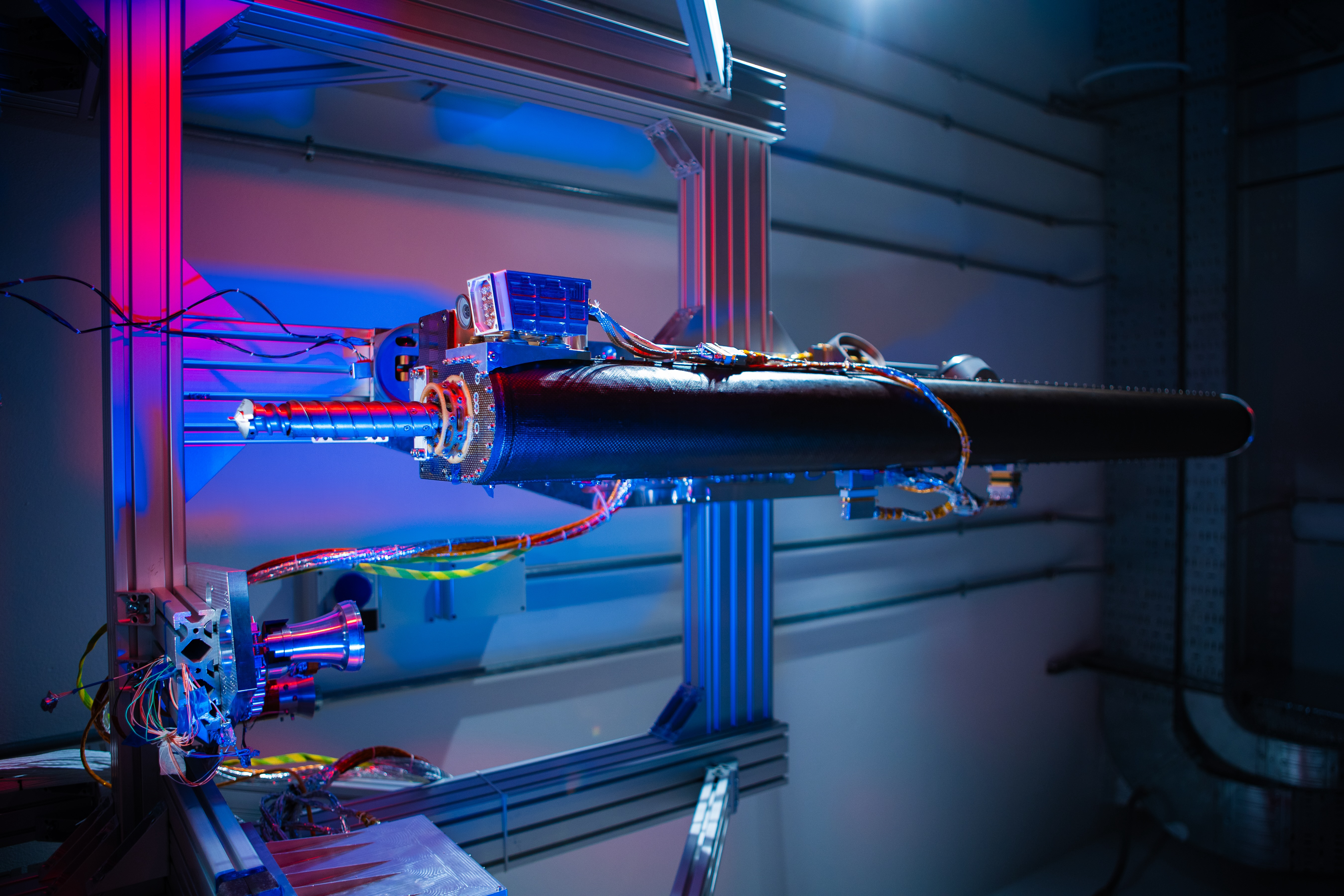

A second plane, equipped with the agency’s AVIRIS-NG instrument, will estimate carbon and sediment in the water, supplementing the data being collected by boat and covering a larger area. It will also return data on the types and quantity of plants and vegetation present.

NASA’s UAVSAR instrument will be on the third plane and measure changes in water levels within the marshes, which will give researchers a clearer picture of how the wetlands are connected to the open water channels and how water flows within them.

Scientists will use the combination of these data to calibrate and validate models that will be used to predict the gain and loss of land in the delta under different scenarios of sea level rise, river flows, and watershed management.

Why It Matters

Deltas protect inland areas from wind and flooding during storms, they serve as a first line of defense against sea level rise, and they are home to many species of plants and wildlife. The Mississippi River Delta, one of the world’s largest, also helps drive the local and national economies via shipping, commercial fishing, and tourism.

But the delta is quickly losing land area: Over the last 80 years, it has shrunk by some 2,000 square miles (5,000 square kilometers) – roughly an area the size of the state of Delaware. Naturally occurring deltas evolve in a delicate balance between land loss from soil compaction and ground sinking – which can be accelerated by the extraction of subterranean water, petroleum, and natural gas – and the buildup of soil from accumulated sediment and plant growth. When deltas don’t accumulate sediment fast enough to offset sea level rise and ground sinking, they essentially drown.

“Millions of people live on and live from services provided by coastal deltas like the Mississippi River Delta. But sea level rise is causing many major deltas to lose land or disappear altogether, taking those services with them,” Simard said. “We hope to be able to predict where and why some parts of the region will disappear and others are likely to survive.”

Despite the delay, the team had little downtime over the past year. They have been working hard to fine-tune their algorithms and models, to make upgrades to some of their equipment, and to finalize a new set of logistics brought on by the pandemic.

“Obviously, one of our priorities is getting the highest quality data, but it has also been ensuring that everyone being sent into the field is comfortable with the plan,” Jones said. “We’ve had very open communication about that, and overall, everyone has done a fantastic job navigating the complicated logistics needed for us to have a safe and successful campaign.”

The Delta-X team expects to have the first science results from the campaign later this year. Planning for a second campaign in the fall is also underway.

Jane J. Lee / Ian J. O’Neill

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-0307

jane.j.lee@jpl.nasa.gov / ian.j.oneill@jpl.nasa.gov

Written by Esprit Smith, NASA’s Earth Science News Team

2021-070