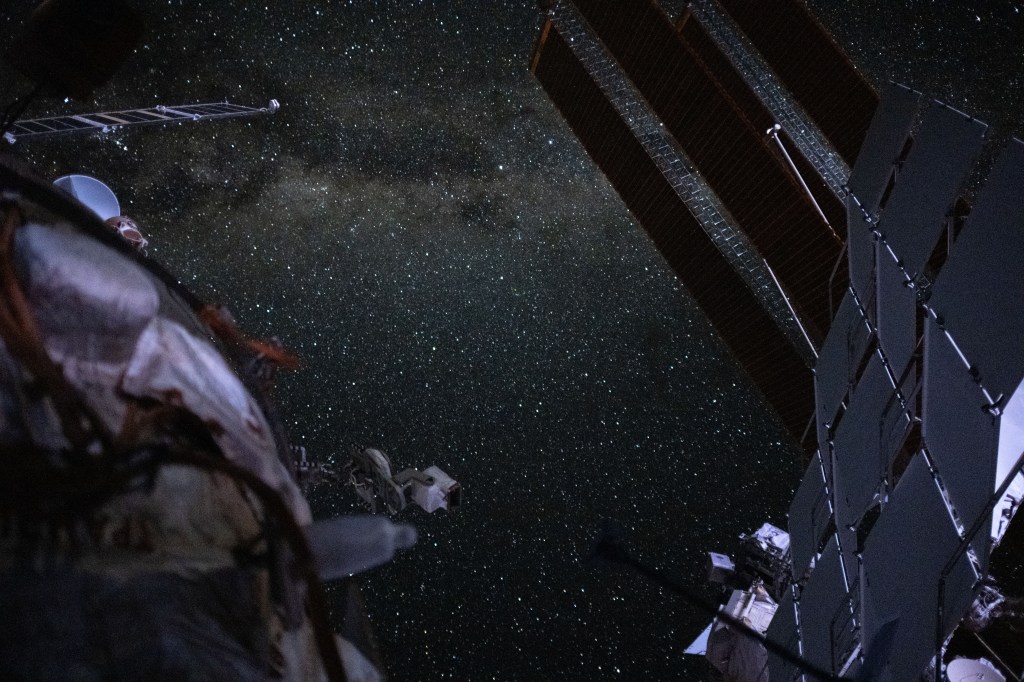

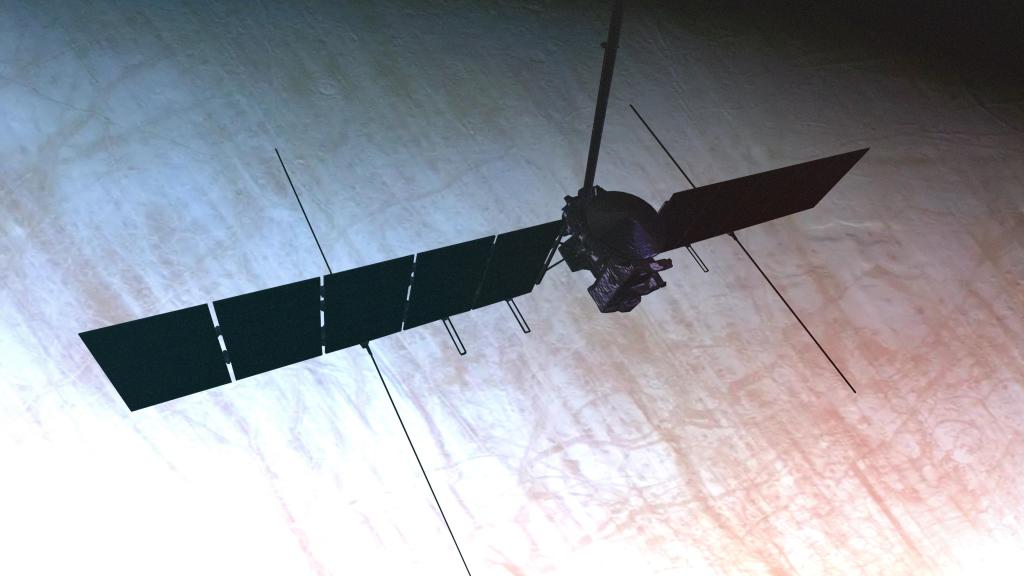

In the American Wild West, high noon was a time for duels and showdowns. When it comes to the history of the universe, cosmic noon featured fireworks of a different sort. Some 2 to 3 billion years after the big bang most galaxies went through a growth spurt, forming stars at a rate hundreds of times higher than we see in our own galaxy, the Milky Way, today. When it launches by May 2027, NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope promises to bring new insights into the heyday of star formation.

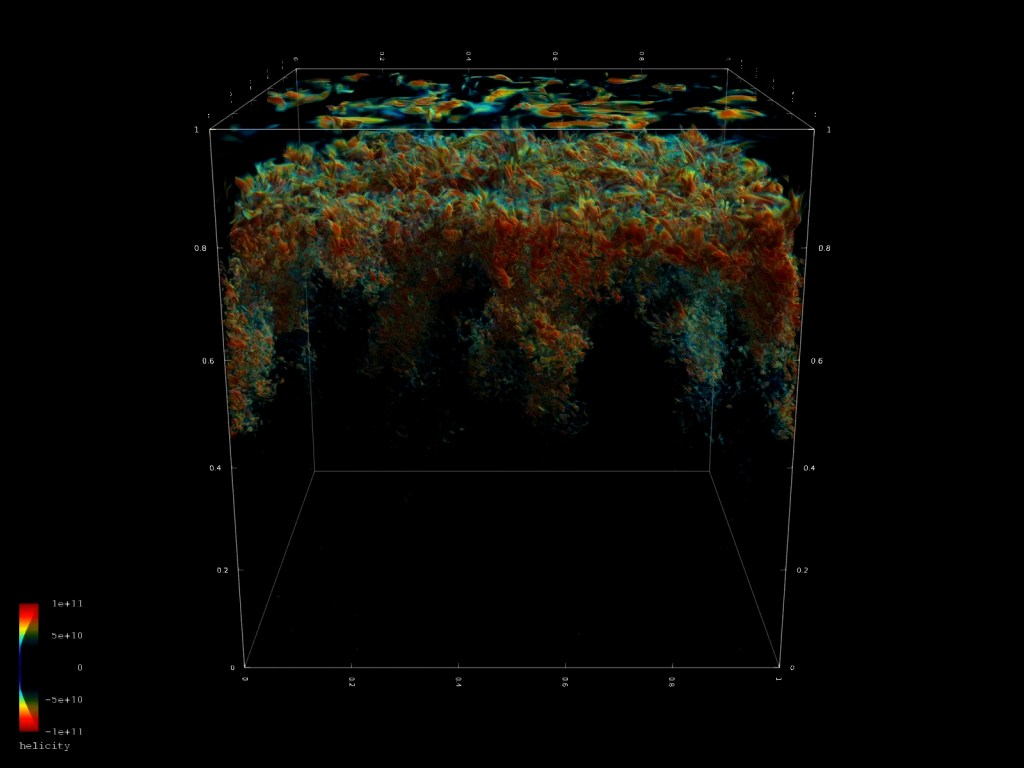

Cosmic noon is an important time in the universe’s history because it shaped what galaxies are like today. But many questions remain unanswered. Why did star formation peak and then decline? Why did some galaxies suddenly stop forming stars while others faded out gradually? How important were local influences like the number of galactic neighbors in shaping this evolution?

To answer these questions, astronomers need a bountiful sample of galaxies from that time period to study. Roman’s power will lie in its ability to capture thousands of objects of interest in a single view. With such a large survey, scientists won’t have to pick and choose their preferred targets in advance, which can lead to unintended biases.

“With a field of view 100 times wider than the Hubble Space Telescope, Roman can change the astronomical landscape by being so efficient,” said Kate Whitaker, assistant professor of Astronomy at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. Whitaker’s research focuses on studying the regulation of star formation and quenching in massive galaxies in the early universe.

Roman’s wide field of view also will enable astronomers to put individual galaxies into context by seeing how their growth spurts, and subsequent slow-downs, vary depending on their location within the cosmic “web” – the large-scale structure of the universe.

“You take one image, and you get everything. We’ll see what and where the interesting objects are,” said Casey Papovich, professor of Astronomy at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas. Papovich’s research includes quantifying the growth and assembly of stellar mass in galaxies in the early universe.

Going Beyond Imagery

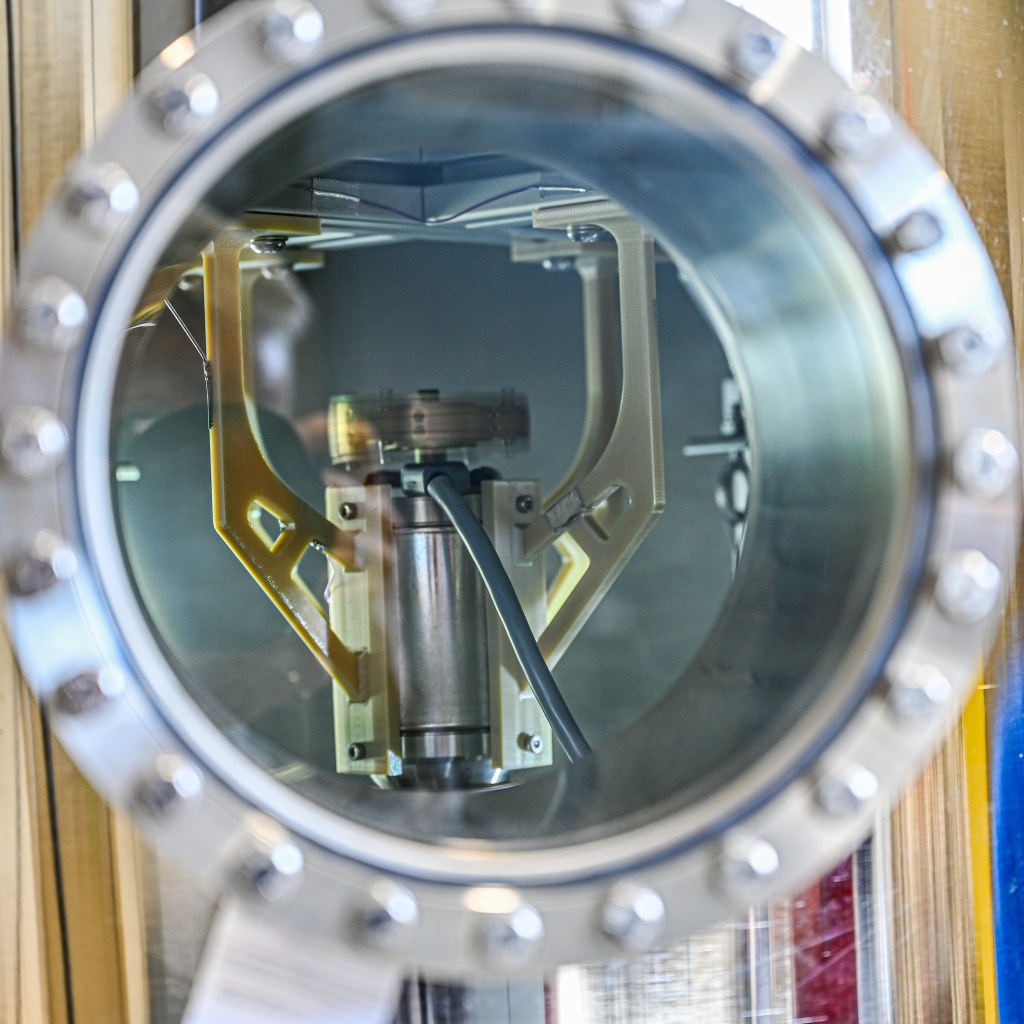

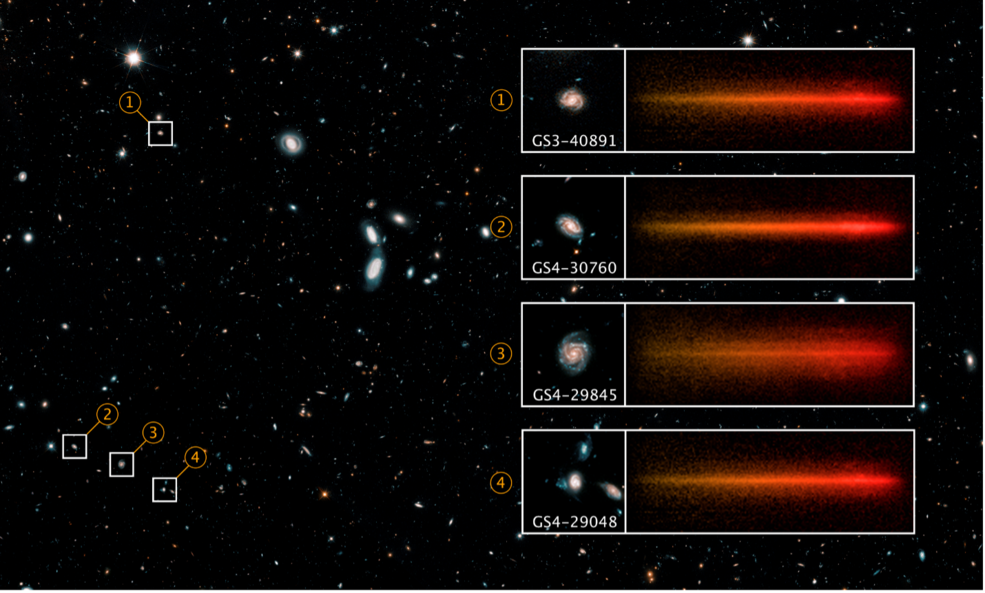

While images can help astronomers spot galaxies of interest, much more information can be gleaned by spreading a galaxy’s light out into a spectrum. Papovich, with Vicente (Vince) Estrada-Carpenter of St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, Texas, and their colleagues, has pioneered a technique for extracting the light from all the stars in a galaxy combined.

By examining a galaxy’s spectrum you can learn about the ages of its stars, its star formation history, how many heavy chemical elements it contains, and more. By doing this for a large number of early galaxies, astronomers can learn about the processes that drove and eventually brought an end to this period of rapid growth.

Roman’s power can be boosted even further by observing distant galaxies whose light has been distorted by a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. The gravity of an intervening galaxy cluster can magnify and brighten the light from a more distant galaxy, allowing astronomers to study the background galaxy in more detail than would otherwise be available.

Whitaker is already using this technique with Hubble to study the cores of young galaxies versus their outskirts. This work seeks to determine if star formation shuts off from the outside-in or inside-out – that is, from the galaxy’s outskirts to its center or vice versa.

“Galaxy quenching – a sudden end to star formation – can be a fast process on cosmological timescales. As a result, catching one in the act is difficult because they’re so rare,” said Whitaker. “Roman will help us find those rare examples.”

While Roman’s space-based view will provide excellent sharpness and stability, ground-based observatories also will come into play in studying cosmic noon. For example, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array can measure the gas and dust content of distant galaxies. And future 30-meter-class telescopes will be able to measure exquisite details in galaxy spectra due to their ability to collect lots of light.

“Roman and ground-based observatories will complement each other. Roman will single-handedly and efficiently identify and characterize the most interesting galaxies in large fields of view. We then can go back with ground-based telescopes to study them in more detail,” explained Papovich.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is managed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, with participation by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Caltech/IPAC in Southern California, the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, and a science team comprising scientists from various research institutions. The primary industrial partners are Ball Aerospace and Technologies Corporation in Boulder, Colorado; L3Harris Technologies in Melbourne, Florida; and Teledyne Scientific & Imaging in Thousand Oaks, California.

By Christine Pulliam

Media contacts:

Claire Andreoli

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Christine Pulliam

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md.