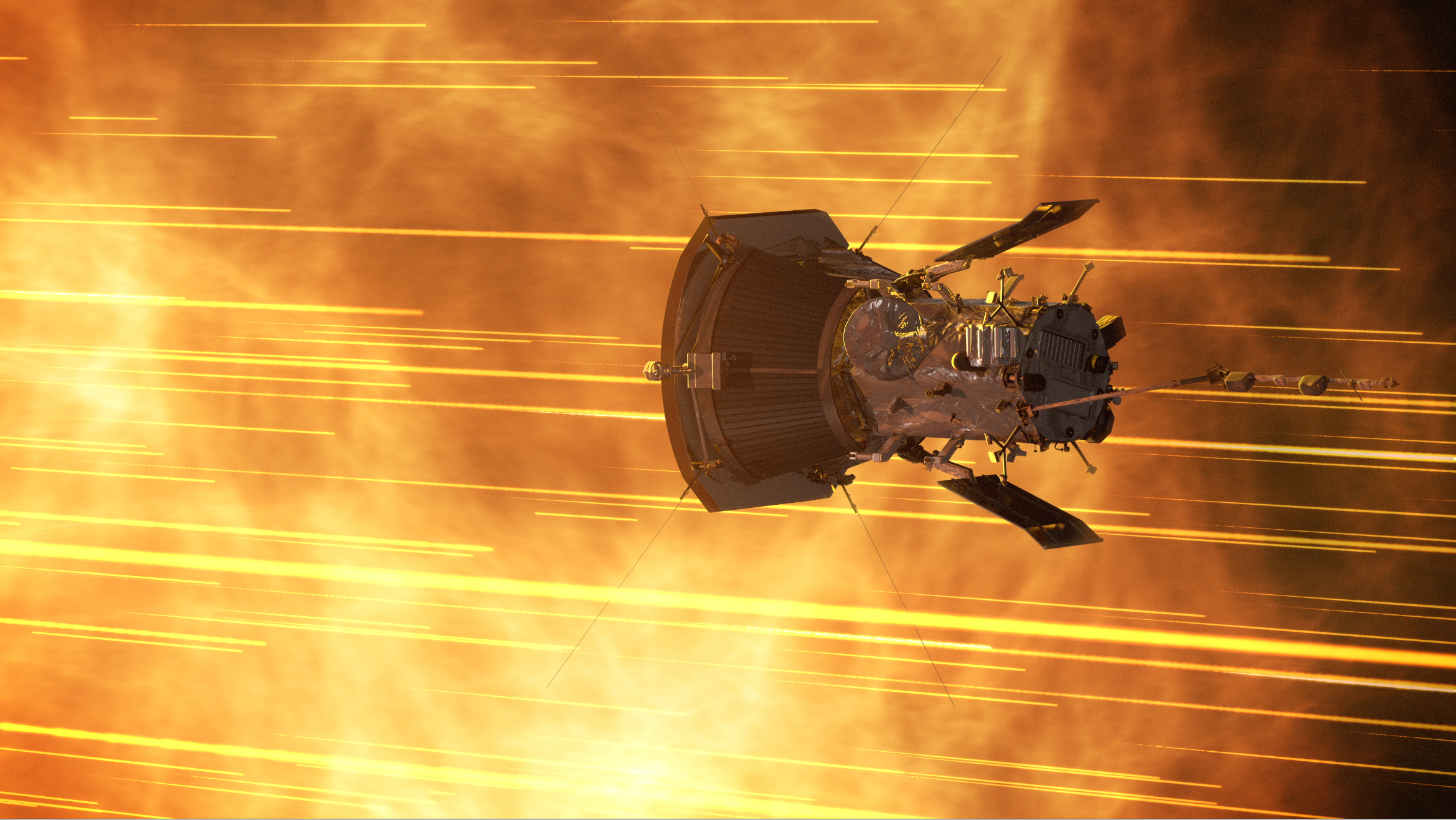

Earth sails the solar system in a ship of its own making: the magnetosphere, the magnetic field that envelops and protects our planet. The celestial sea we find ourselves in is filled with charged particles flowing from the Sun, known as the solar wind. Just as ocean waves follow the wind, scientists expected that waves traveling along the magnetosphere should ripple in the direction of the solar wind. But a new study reveals some waves do just the opposite.

Studying these magnetospheric waves, which transport energy, helps scientists understand the complicated ways that solar activity plays out in the space around Earth. Changing conditions in space driven by the Sun are known as space weather. That weather can impact our technology from communications satellites in orbit to power lines on the ground. “Understanding the boundaries of any system is a key problem,” said Martin Archer, a space physicist at Imperial College London who led the new study, published today in Nature Communications. “That’s how stuff gets in: energy, momentum, matter.”

Archer focuses on surface waves, meaning waves that require a boundary — in this case, the edge of the magnetosphere — to travel along. Previously, he and his colleagues established this boundary vibrates like a drum. When a strong burst of solar wind beats against the magnetosphere, waves race towards Earth’s magnetic poles and get reflected back.

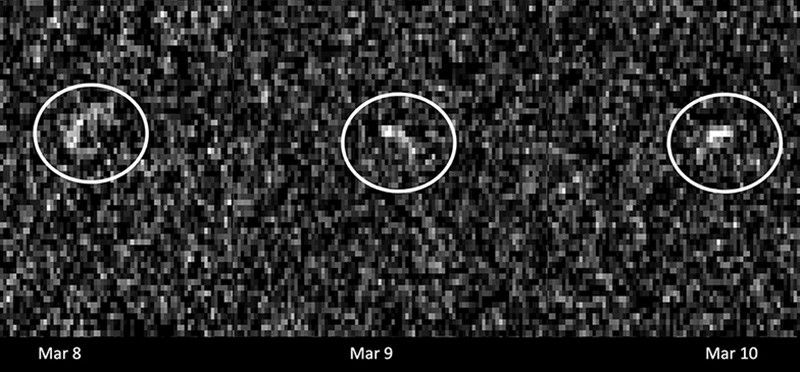

The latest work considers the waves that form across the entire surface of the magnetosphere, using a combination of models and observations from NASA’s THEMIS mission, Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms.

The researchers found when solar wind pulses strike, the waves that form not only race back and forth between Earth’s magnetic poles and the front of the magnetosphere, but also travel against the solar wind. Archer likened these two kinds of movement to crossing a river: A boat can go from one riverbank to the other (traveling towards the poles) and upstream (against the solar wind). At the front of the magnetosphere, these waves appear to stand still.

The THEMIS satellites’ observations from within the magnetosphere first hinted some waves might be traveling against the solar wind. The researchers used models to illustrate how the energy of the wind coming from the Sun and that of the waves going against it could cancel each other out. It’s similar to what happens if you try walking up a downwards escalator. “It’s going to look like you’re not moving at all, even though you’re putting in loads of effort,” Archer said.

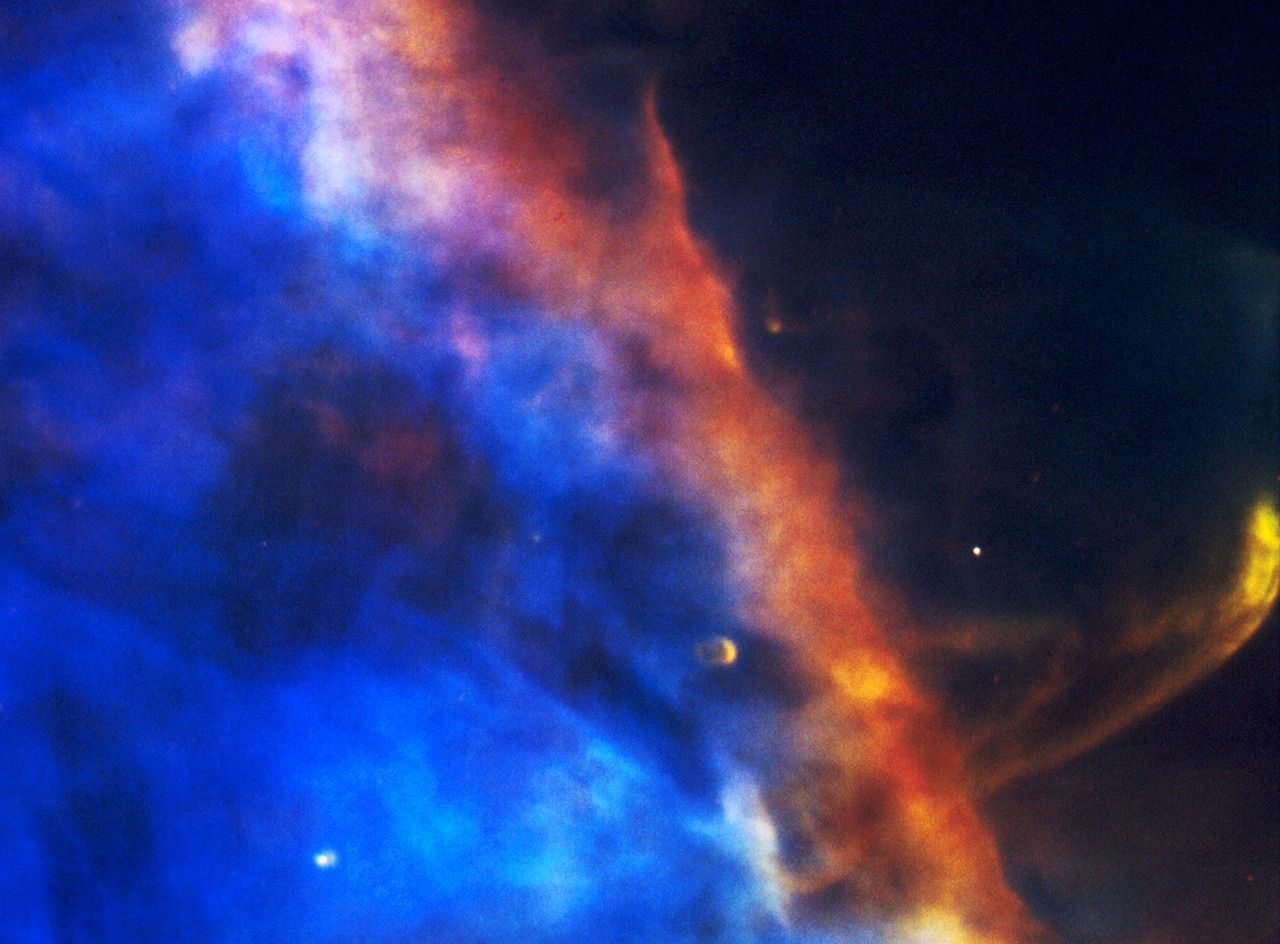

These standing waves can persist longer than those that travel with the solar wind. That means they’re around longer to accelerate particles in near-Earth space, leading to potential impacts in the radiation belts, aurora, or ionosphere. Archer expects standing waves may occur elsewhere in the universe, from the magnetospheres of other planets to the peripheries of black holes. Studying the waves close to home can help scientists understand such distant boundaries.

By translating the wave models and data into the audible range, we can listen to the sound of these curious waves.

Credit: Martin Archer/CCMC/NASA

By Lina Tran

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.