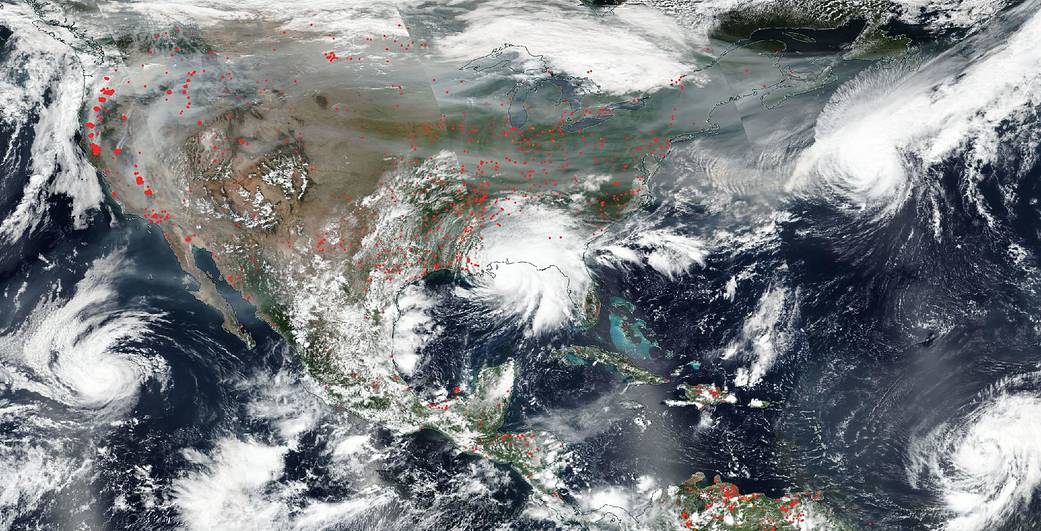

By most accounts, 2020 has been a rough year for the planet. It was the warmest year on record, just barely exceeding the record set in 2016 by less than a tenth of a degree according to NASA’s analysis. Massive wildfires scorched Australia, Siberia, and the United States’ west coast – and many of the fires were still burning during the busiest Atlantic hurricane season on record.

“This year has been a very striking example of what it’s like to live under some of the most severe effects of climate change that we’ve been predicting,” said Lesley Ott, a research meteorologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

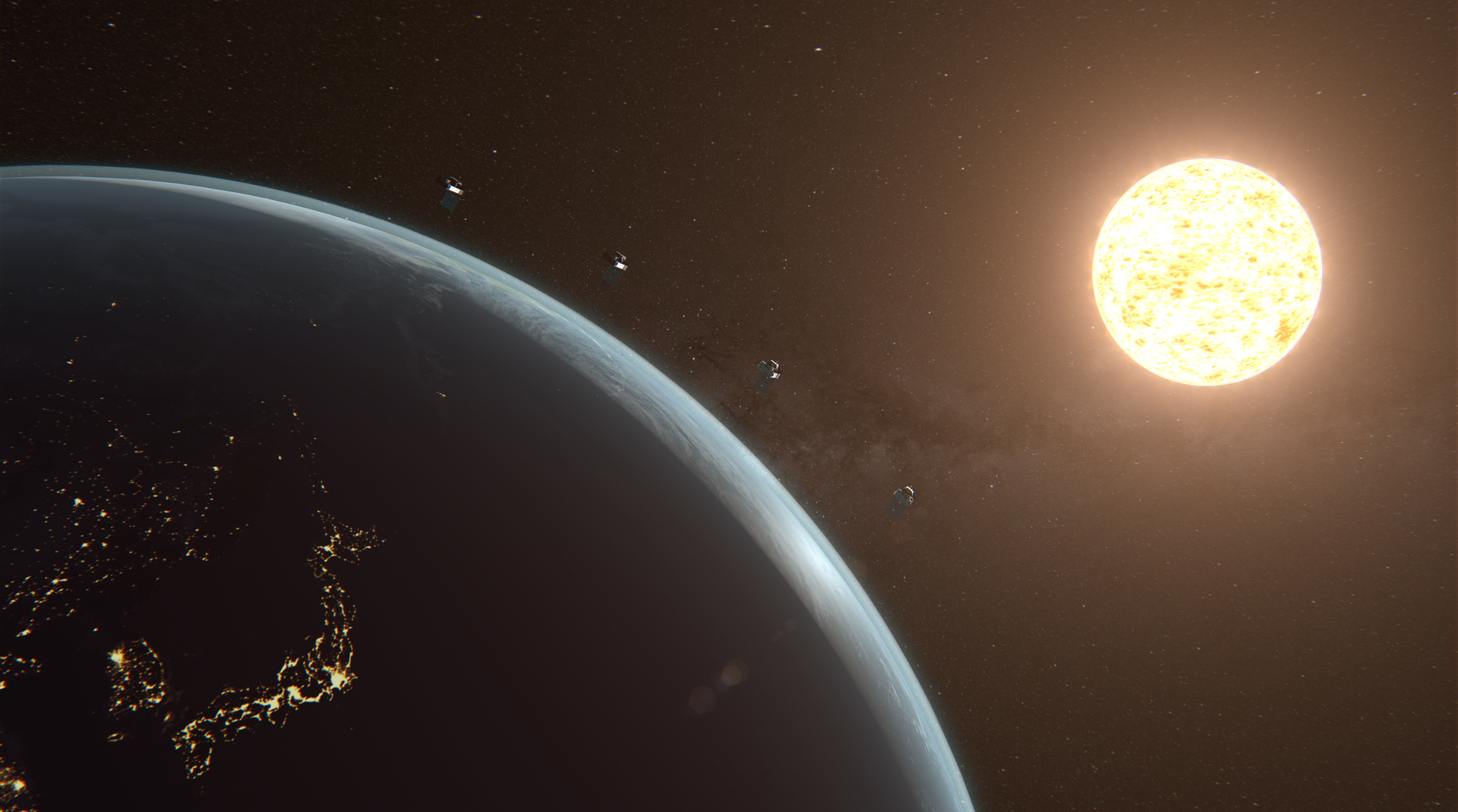

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Scientific Visualization Studio/Katie Jepson

Decades of greenhouse gas emissions set the stage for this year’s events

Human-produced greenhouse gas emissions are largely responsible for warming our planet. Burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas releases greenhouse gases – such as carbon dioxide – into the atmosphere, where they act like an insulating blanket and trap heat near Earth’s surface.

“The natural processes Earth has for absorbing carbon dioxide released by human activities – plants and the ocean – just aren’t enough to keep up with how much carbon dioxide we’re putting into the atmosphere,” said Gavin Schmidt, climate scientist and Director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) in New York City.

Carbon dioxide levels have increased by nearly 50% since the Industrial Revolution 250 years ago. The amount of methane in the atmosphere has more than doubled. As a result, during this period, Earth has warmed by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit (just over 1 degree Celsius).

Climate modelers have predicted that, as the planet warms, Earth will experience more severe heat waves and droughts, larger and more extreme wildfires, and longer and more intense hurricane seasons on average. The events of 2020 are consistent with what models have predicted: extreme climate events are more likely because of greenhouse gas emissions.

Heat waves fanned the flames of extreme wildfires across the globe

Climate change has led to longer fire seasons, as vegetation dries out earlier and persistent high temperatures allow fires to burn longer. This year, heat waves and droughts added fuel for the fires, setting the stage for more intense fires in 2020.

The Australian bushfires that started in 2019 continued into 2020 due to sustained high temperatures, burning vast forested areas and sending smoke around the globe. The heat wave helped the fires grow rapidly, burning over 20% of the Australian temperate forest biome. Fire-induced thunderstorms called pyrocumulonimbus events resulted in smoke plumes that reached a record-breaking 18 mile (30 kilometer) altitude – crossing into the stratosphere. Smoke released from the bushfires circumnavigated the globe before returning to the skies over Australia.

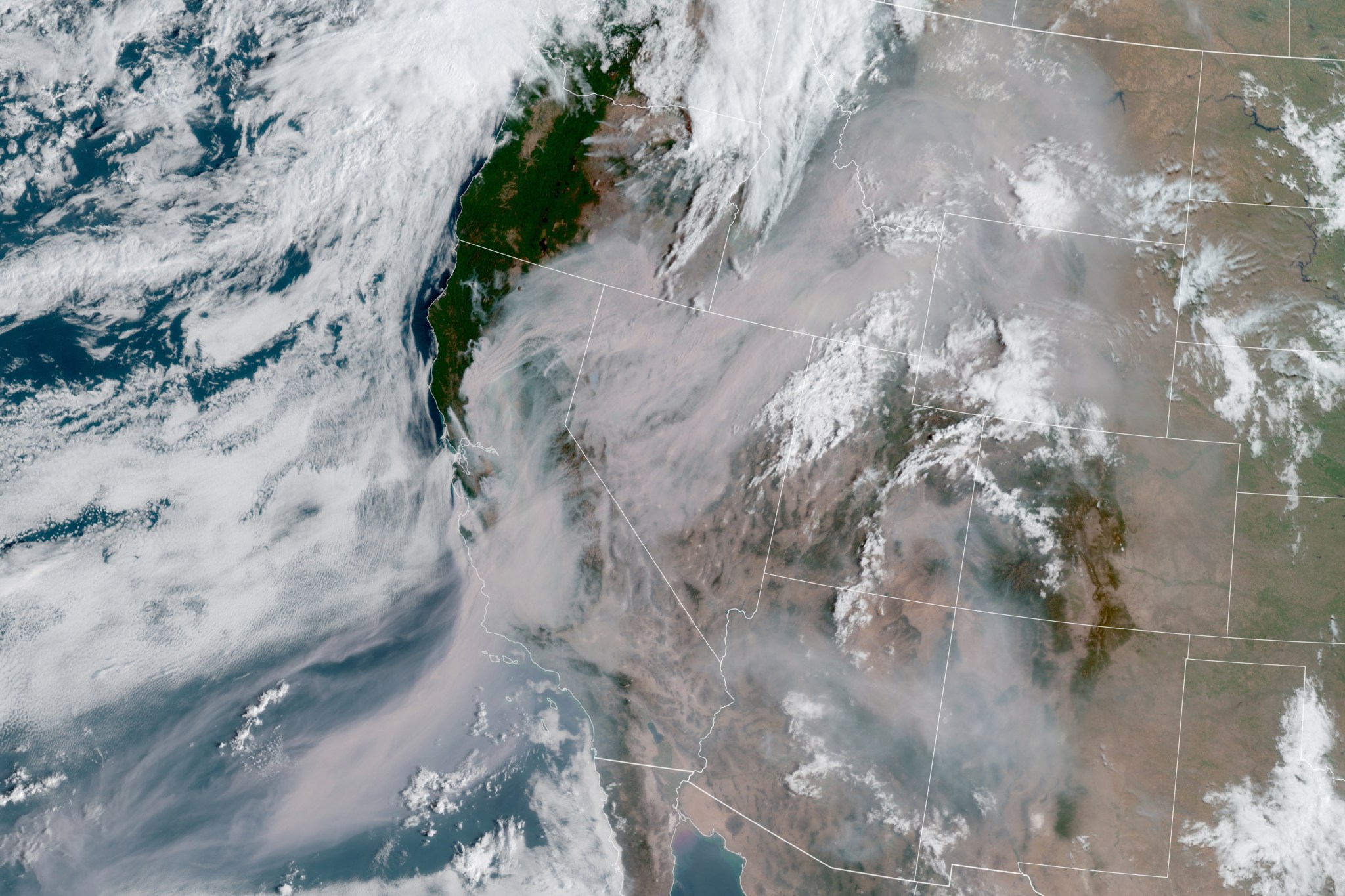

Hundreds of wildfires burned throughout the western United States this past year, making it the most active fire season on record. Fires in Colorado grew quickly as heat waves enabled the fire to burn faster and hotter. In California, more than 650 fires were actively burning in late August; the largest of these – the August Complex Fire – burned over a million acres.

A heat wave hit the Arctic Circle this summer, with temperatures rising above 100 degrees Fahrenheit in some parts of Siberia. This heat wave triggered a wildfire outbreak that reignited “zombie fires” from the previous year.

Zombie fires can occur when fires burn in areas with permafrost, carbon-rich soil that typically stays frozen year-round. Zombie fires burn so deep in the permafrost layer that they can continue to smolder under a blanket of snow throughout winter and can reemerge in the spring.

Wildfires in the Arctic have long-term impacts on Earth’s climate system. Tundra and boreal fires release methane and carbon in these regions that have been accumulating for centuries into the atmosphere. Burning also creates the conditions for continued permafrost layer thaw, resulting in increased greenhouse gas emissions for years to come.

Earth is continuing to lose a key player in the fight against climate change: ice

This year wasn’t a record-breaker for ice loss at sea or on land. But ice plays a key role in regulating Earth’s temperature, and the overall trends show we’re continuously losing ice around the globe.

The planet is losing about 13.1% of Arctic sea ice by area each decade, according to sea ice minimum data from NASA and the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. Studies of sea ice thickness have also shown that sea ice is a lot thinner than it used to be.

Sea ice floating in the Arctic acts like an insulating barrier, preventing the ocean from heating the atmosphere. Sea ice is also so bright that it reflects heat energy from the Sun away from Earth. Without sea ice, that energy would be absorbed by the darker ocean waters, leading to even higher sea surface temperatures.

Credits: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio / Data from DMSP’s SSM/I and SSMIS satellites

Each year, Arctic sea ice melts and regrows, reaching its minimum extent around mid-September and maximum extent in March. This year had the second lowest Arctic sea ice summer extent on record. Arctic sea ice also got a slow start regrowing this year due to warmer air temperatures, which doesn’t bode well for the sea ice extent in 2021.

“When the ice has a slow start to regrow, it’s hard to catch up,” said Tom Neumann, glaciologist and Chief of the Cryospheric Sciences Lab at Goddard.

On land, the Greenland ice sheet is continuing to melt, and the record-breaking temperatures of 2020 didn’t help. This year, 23.1 million square kilometers of Greenland’s ice sheet (about 70 percent of the ice sheet’s surface) reached the melting point. Glaciers and mountain ice caps in places like Alaska, South America, and High Mountain Asia are continuing to melt, contributing more than either Greenland or Antarctica to sea level rise, which affects coastal communities around the world.

The situation in the Arctic is a direct consequence of climate change – and a foreshadowing of what’s to come in other places. “The Arctic is like the canary in the coal mine because the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet,” said Neumann. On average, the Arctic is warming three times faster.

High sea surface temperatures intensified storms in the busiest Atlantic hurricane season

This year brought one of the busiest and most intense Atlantic hurricane seasons on record, with 30 named storms.

“We had more named storms than we’ve ever had before,” said Jim Kossin, an atmospheric scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) based in Madison, Wisconsin. More storms and a longer hurricane season are probably a result of regional conditions rather than global warming, Kossin said. However, climate change warms the ocean’s surface and drives storm intensification – the change in windspeeds that, for example, raises a Category 4 storm to a Category 5. That warmer water at the surface acts like fuel, providing energy in the form of heat that the hurricane uses to intensify more quickly. This year’s Atlantic hurricane season brought many examples of storms that intensified quickly: ten of the 30 named storms showed rapid intensification.

The planet is also seeing more slow-traveling hurricanes that stall, bringing prolonged rainfall to an area, likely as a result of climate change. Warmer air holds more water vapor (about 7% more water per 1 degree C of warming). The planet is warming at different rates around the globe, which can reduce the temperature and pressure gradients, thus slowing the winds that push hurricanes. That means storms are more likely to stall, bringing sustained high winds and dumping massive amounts of rain in one area. Hurricanes Sally and Eta – which respectively made landfall in Alabama in September and Central America in November – were prime examples.

“Global warming won’t necessarily increase overall tropical storm formation, but when we do get a storm it’s more likely to become stronger. And it’s the strong ones that really matter,” Kossin said.

What does the future hold?

This year we experienced firsthand the ways that more heat is expressed on our planet. The large wildfires, intense hurricanes, and ice loss we saw in 2020 are direct consequences of human-induced climate change. And they’re projected to continue and escalate into the next decade – especially if human-induced greenhouse gas emissions continue at the current rate.

“This isn’t the new normal,” said Schmidt. “This is a precursor of more to come.”

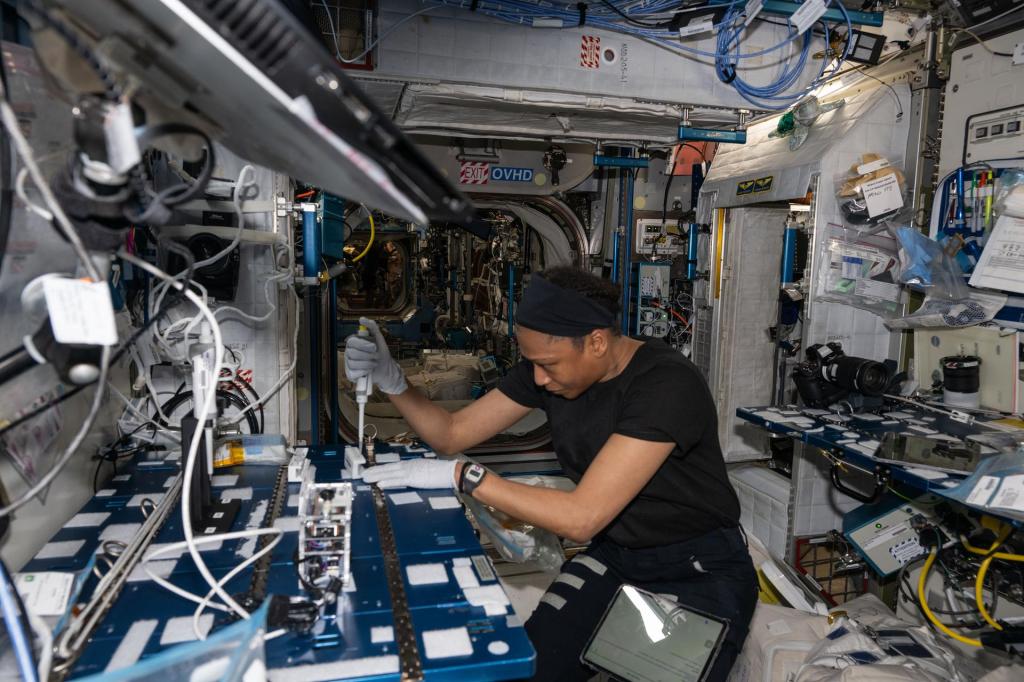

To help us understand and prepare for our planet’s future, NASA observes and learns about Earth from space. By collecting a variety of data, NASA scientists are able to better understand how Earth operates as a system and create models to predict what the next decades will bring, providing information that helps decisionmakers around the world.

By Sofie Bates

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.