UPDATE Oct. 8, 2021: The CLASP2.1 mission was successfully launched at 11:40 a.m. MT (1:40 p.m. EDT), Oct. 8, from the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Flying on a NASA Black Brant IX sounding rocket, the payload reached an altitude of 169 miles. Preliminary indications are that good data was achieved.

UPDATE Oct, 6, 2021: The launch of the CLASP2.1 mission has been rescheduled for Friday, Oct. 8, 2021, from the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. The launch window is 11:30 a.m. – 12:08 p.m. MT. The launch was postponed from the Oct. 5 launch attempt due to a communications issue with the payload during the countdown.

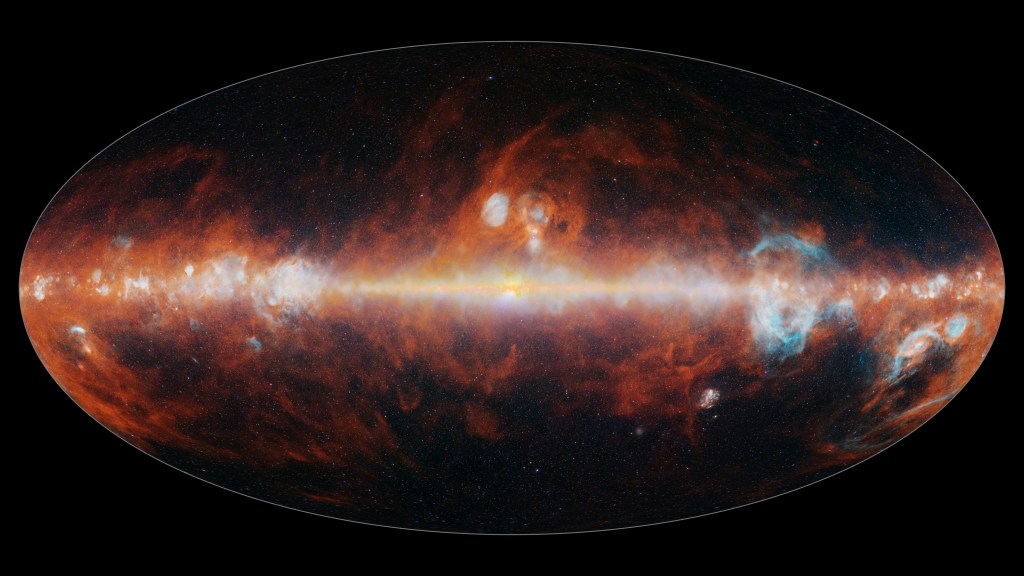

Measuring a magnetic field isn’t so hard if you’re inside of it. Measuring a magnetic field remotely – whether from across a room, across a country, or 93 million miles away – is an entirely different story. But that’s exactly what a team of NASA scientists and international collaborators aim to do with the CLASP2.1 mission: measure the magnetic field in a critical slice of the Sun’s atmosphere called the chromosphere.

CLASP2.1, short for Chromospheric Layer Spectropolarimeter 2.1, will make these measurements from a NASA sounding rocket. Sounding rockets are small rockets that carry instruments into space for five to ten minutes before falling back down to Earth. The launch window for the CLASP2.1 sounding rocket mission opens at 11:30 a.m. MT on Oct. 5, 2021, at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

The upcoming flight will be the CLASP instrument’s third trip to space. The current work builds on previous flights to help scientists better understand the magnetic field of the Sun’s chromosphere, so named for its bright red appearance during total solar eclipses.

Magnetism drives much of the Sun’s activity, such as solar flares. According to David McKenzie, CLASP2.1 principal investigator and astrophysicist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, magnetism is what makes astrophysics interesting. “That’s especially true in solar physics,” he said.

Flares and other activity on the Sun’s surface can affect people both on Earth and in space. While harmful radiation from a flare can’t pass through Earth’s atmosphere to physically affect people on the ground, these bursts of radiation can interfere with radio and GPS signals, and other effects of solar activity can prematurely damage metals in things like oil pipelines and nuclear power plants. Extremely intense solar activity can even cause power outages. The massive doses of radiation that accompany solar flares also pose a threat to astronauts outside the protection of Earth’s magnetic field.

“By understanding the magnetic field in the Sun, we can learn to predict when these events are going to happen,” McKenzie said. One day, the information could help scientists warn energy companies about high-risk events or tell astronauts when it’s safe to do a spacewalk.

But right now, we don’t know much about the magnetic field in the chromosphere, the lower layer of the Sun’s atmosphere where magnetic forces give rise to solar eruptions. That’s largely because it is so hard to measure.

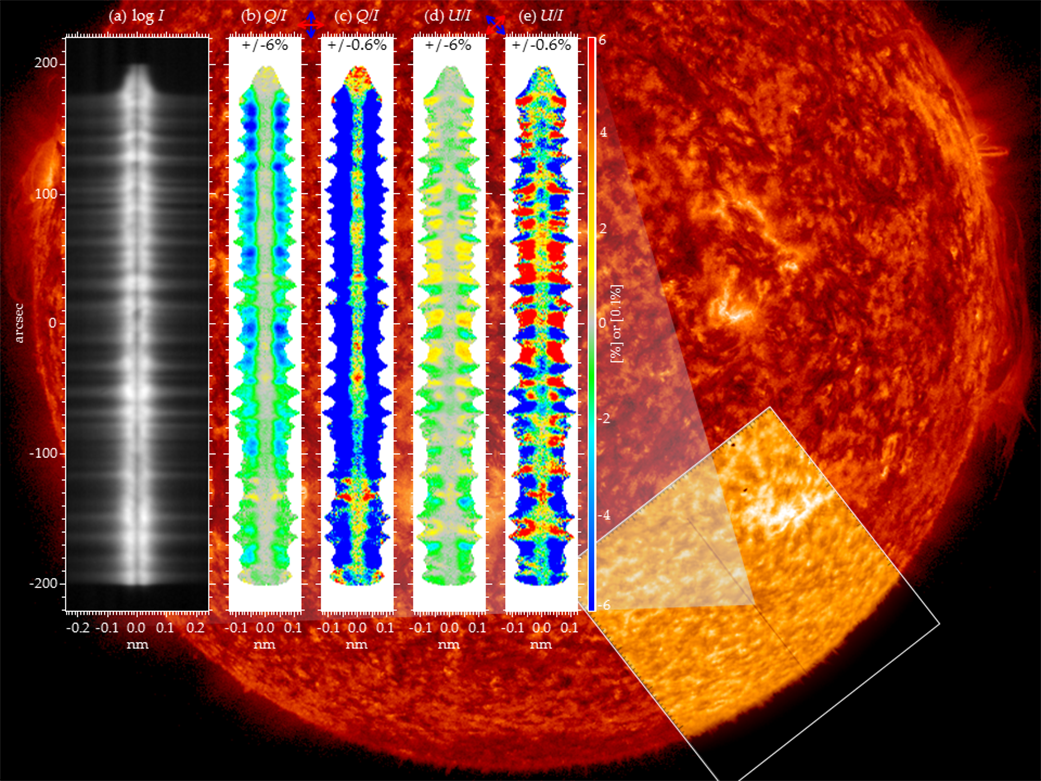

Enter CLASP and its subsequent missions, CLASP2 and CLASP2.1. Since researchers can’t measure the magnetic field directly, CLASP was designed to measure the effects of the magnetic field in the chromosphere, where super-hot solar material emits ultraviolet light.

The Sun-gazing CLASP telescope feeds ultraviolet light to a spectrograph, an instrument that separates light into its component wavelengths. Each wavelength appears as a “notch” in the light spectrum – scientists call them spectral lines. In the presence of a magnetic field, these lines sometimes split. (This phenomenon, known as the Zeeman Effect, is named for Dutch physicist Pieter Zeeman, who first observed it in 1896. Zeeman won a Nobel Prize for the discovery, which is foundational to astrophysics.)

This splitting of spectral lines also polarizes the light, so that individual light waves tend to oscillate in a certain direction, or even in a circular (clockwise or counterclockwise) motion. Equipped with a specialized filter – essentially a more precise version of polarized sunglasses – CLASP2.1 will measure this polarization. With this information, the scientists can determine precisely how much the chromosphere’s magnetic field has split the spectral lines.

“The amount of the splitting depends on the strength of the magnetic field,” McKenzie said. “So, if you can measure the amount of splitting, then you have a remote measurement of how strong the magnetic field is.”

CLASP2.1, which uses the same instrument as previous CLASP missions, has the same setup as CLASP2 but will test a new capability. Instead of measuring just one sliver of the Sun, it will look at 12 to 15 equal-sized slivers during its six minutes in space. (McKenzie says it would require many hundreds of these segments to span the Sun.) Each sliver reveals a snapshot of that section of the Sun’s ever-changing magnetic field. The more slivers they can cover, the broader a swath of the magnetic field the scientists can visualize.

McKenzie hopes to eventually put the instrument on a free-flying satellite where it could take continuous measurements of the Sun. Before a piece of scientific equipment earns a spot aboard a satellite, though, the researchers working on it must demonstrate that it works. Sounding rocket missions like this one allow McKenzie and the rest of the team to test and refine their equipment. “It’s technology development, it’s proof of concept, we work out some of the bugs,” he said. And, in the process, the team produces snapshots of the chromosphere’s magnetic fields.

By Anna Blaustein

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.