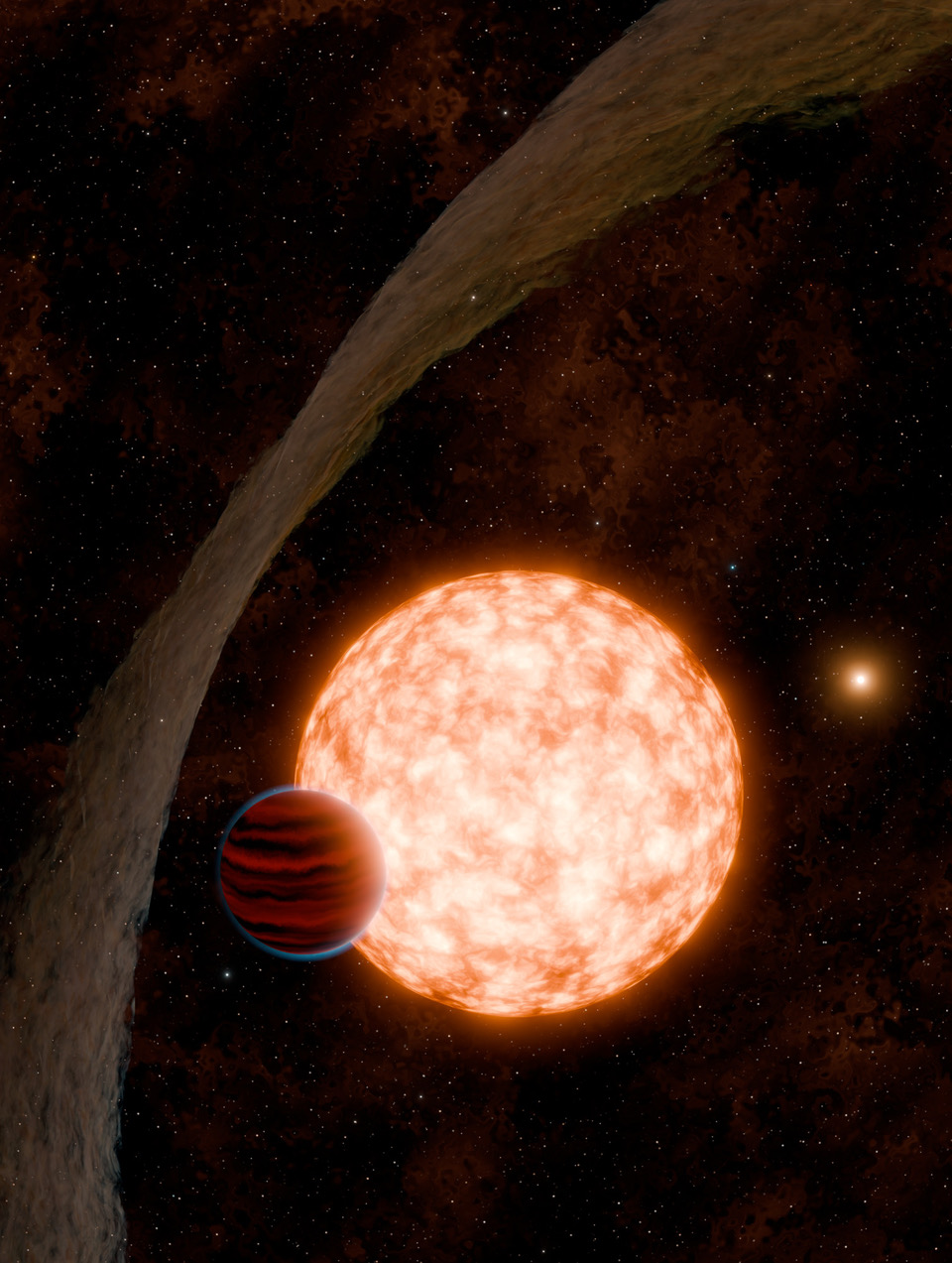

Quasars are very bright, distant and active supermassive black holes that are millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun. Typically located at the centers of galaxies, they feed on infalling matter and unleash fantastic torrents of radiation. Among the brightest objects in the universe, a quasar’s light outshines that of all the stars in its host galaxy combined, and its jets and winds shape the galaxy in which it resides.

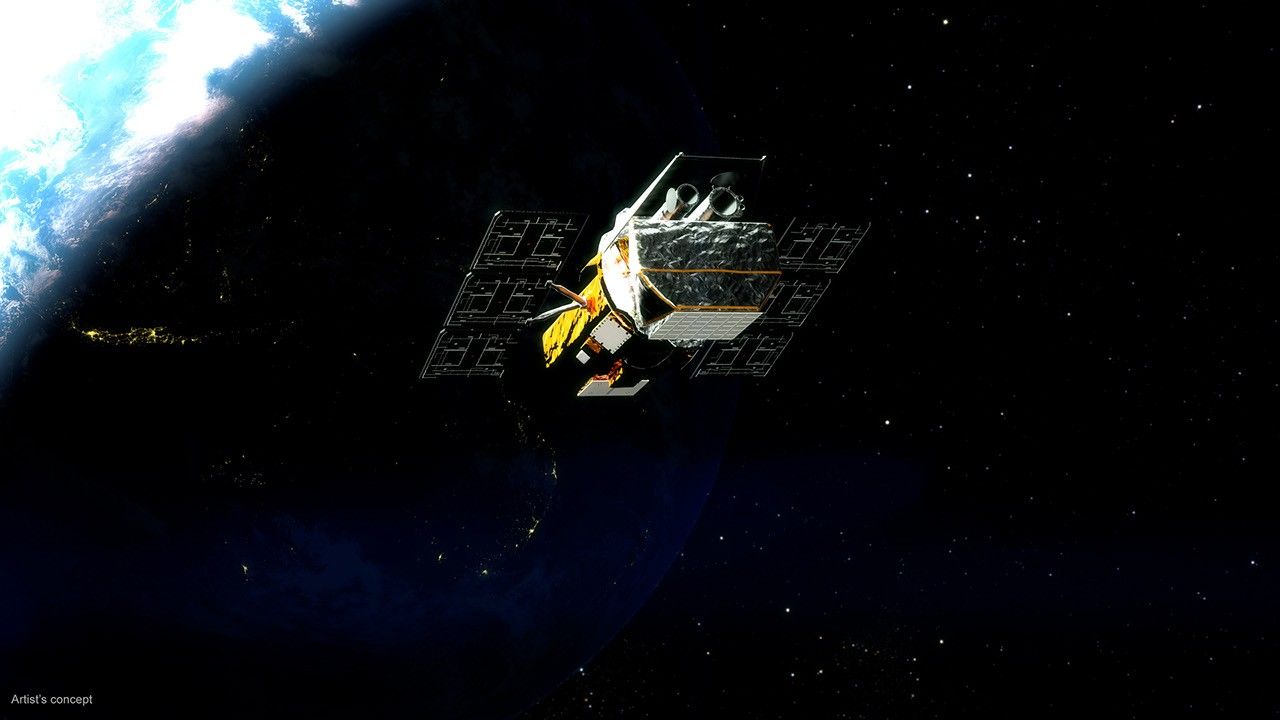

Shortly after its launch later this year, a team of scientists will train NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope on six of the most distant and luminous quasars. They will study the properties of these quasars and their host galaxies, and how they are interconnected during the first stages of galaxy evolution in the very early universe. The team will also use the quasars to examine the gas in the space between galaxies, particularly during the period of cosmic reionization, which ended when the universe was very young. They will accomplish this using Webb’s extreme sensitivity to low levels of light and its superb angular resolution.

Webb: Visiting the Young Universe

As Webb peers deep into the universe, it will actually look back in time. Light from these distant quasars began its journey to Webb when the universe was very young and took billions of years to arrive. We will see things as they were long ago, not as they are today.

“All these quasars we are studying existed very early, when the universe was less than 800 million years old, or less than 6 percent of its current age. So these observations give us the opportunity to study galaxy evolution and supermassive black hole formation and evolution at these very early times,” explained team member Santiago Arribas, a research professor at the Department of Astrophysics of the Center for Astrobiology in Madrid, Spain. Arribas is also a member of Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) Instrument Science Team.

The light from these very distant objects has been stretched by the expansion of space. This is known as cosmological redshift. The farther the light has to travel, the more it is redshifted. In fact, the visible light emitted at the early universe is stretched so dramatically that it is shifted out into the infrared when it arrives to us. With its suite of infrared-tuned instruments, Webb is uniquely suited to studying this kind of light.

Studying Quasars, Their Host Galaxies and Environments, and Their Powerful Outflows

The quasars the team will study are not only among the most distant in the universe, but also among the brightest. These quasars typically have the highest black hole masses, and they also have the highest accretion rates — the rates at which material falls into the black holes.

“We’re interested in observing the most luminous quasars because the very high amount of energy that they’re generating down at their cores should lead to the largest impact on the host galaxy by the mechanisms such as quasar outflow and heating,” said Chris Willott, a research scientist at the Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Centre of the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) in Victoria, British Columbia. Willott is also the Canadian Space Agency’s Webb project scientist. “We want to observe these quasars at the moment when they’re having the largest impact on their host galaxies.”

An enormous amount of energy is liberated when matter is accreted by the supermassive black hole. This energy heats and pushes the surrounding gas outward, generating strong outflows that tear across interstellar space like a tsunami, wreaking havoc on the host galaxy.

Outflows play an important role in galaxy evolution. Gas fuels the formation of stars, so when gas is removed due to outflows, the star-formation rate decreases. In some cases, outflows are so powerful and expel such large amounts of gas that they can completely halt star formation within the host galaxy. Scientists also think that outflows are the main mechanism by which gas, dust and elements are redistributed over large distances within the galaxy or can even be expelled into the space between galaxies – the intergalactic medium. This may provoke fundamental changes in the properties of both the host galaxy and the intergalactic medium.

Examining Properties of Intergalactic Space During the Era of Reionization

More than 13 billion years ago, when the universe was very young, the view was far from clear. Neutral gas between galaxies made the universe opaque to some types of light. Over hundreds of millions of years, the neutral gas in the intergalactic medium became charged or ionized, making it transparent to ultraviolet light. This period is called the Era of Reionization. But what led to the reionization that created the “clear” conditions detected in much of the universe today? Webb will peer deep into space to gather more information about this major transition in the history of the universe. The observations will help us understand the Era of Reionization, which is one of the key frontiers in astrophysics.

The team will use quasars as background light sources to study the gas between us and the quasar. That gas absorbs the quasar’s light at specific wavelengths. Through a technique called imaging spectroscopy, they will look for absorption lines in the intervening gas. The brighter the quasar is, the stronger those absorption line features will be in the spectrum. By determining whether the gas is neutral or ionized, scientists will learn how neutral the universe is and how much of this reionization process has occurred at that particular point in time.

“If you want to study the universe, you need very bright background sources. A quasar is the perfect object in the distant universe, because it’s luminous enough that we can see it very well,” said team member Camilla Pacifici, who is affiliated with the Canadian Space Agency but works as an instrument scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. “We want to study the early universe because the universe evolves, and we want to know how it got started.”

The team will analyze the light coming from the quasars with NIRSpec to look for what astronomers call “metals,” which are elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. These elements were formed in the first stars and the first galaxies and expelled by outflows. The gas moves out of the galaxies it was originally in and into the intergalactic medium. The team plans to measure the generation of these first “metals,” as well as the way they’re being pushed out into the intergalactic medium by these early outflows.

The Power of Webb

Webb is an extremely sensitive telescope able to detect very low levels of light. This is important, because even though the quasars are intrinsically very bright, the ones this team is going to observe are among the most distant objects in the universe. In fact, they are so distant that the signals Webb will receive are very, very low. Only with Webb’s exquisite sensitivity can this science be accomplished. Webb also provides excellent angular resolution, making it possible to disentangle the light of the quasar from its host galaxy.

The quasar programs described here are Guaranteed Time Observations involving the spectroscopic capabilities of NIRSpec.

The James Webb Space Telescope will be the world’s premier space science observatory when it launches in 2021. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.

For more information about Webb, visit www.nasa.gov/webb.

Media contacts:

Ann Jenkins / Christine Pulliam

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Maryland

410-338-4488 / 410-338-4366

jenkins@stsci.edu / cpulliam@stsci.edu

Laura Betz

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

laura.e.betz@nasa.gov