By looking at the Moon, the most complete and accessible chronicle of the asteroid collisions that carved our young solar system, a group of scientists is challenging our understanding of a part of Earth’s history.

The number of asteroid impacts to the Moon and Earth increased by two to three times starting around 290 million years ago, researchers reported in a January 18 paper in the journal Science.

They could tell by creating the first comprehensive timeline of large craters on the Moon formed in the last billion years by using images and thermal data collected by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO). When the scientists compared those to the timeline of Earth’s craters, they found the two bodies had recorded the same history of asteroid bombardment—one that contradicts theories about Earth’s impact rate.

For decades, scientists have tried to understand the rate that asteroids hit the Earth by carefully studying impact craters on continents and by using radiometric dating of the rocks around them to determine the ages of the largest, and thus most intact, ones. The problem is that many experts assumed that early Earth craters have been worn away by wind, storms, and other geologic processes. This idea explained why Earth has fewer older craters than expected compared to other bodies in the solar system, but it made it difficult to find an accurate impact rate and to determine whether it had changed over time.

A way to sidestep this problem is to examine the Moon. Earth and the Moon are hit in the same proportions over time. In general, because of its larger size and higher gravity, about twenty asteroids strike Earth for every one that strikes the Moon, though large impacts on either body are rare. But even though large lunar craters have experienced little erosion over billions of years, and thus offer scientists a valuable record, there was no way to determine their ages until the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter started circling the Moon a decade ago and studying its surface.

“We’ve known since the Apollo exploration of the Moon 50 years ago that understanding the lunar surface is critical to revealing the history of the solar system,” said Noah Petro, an LRO project scientist based at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. LRO, along with new commercial robotic landers under development with NASA, said Petro, will inform the development and deployment of future landers and other exploration systems needed for humans to return to the Moon’s surface and to help prepare the agency to send astronauts to explore Mars. Achieving NASA’s exploration goals is dependent on the agency’s science efforts, which will contribute to the capabilities and knowledge that will enable America’s Moon to Mars exploration approach now and in the future.

“LRO has proved an invaluable science tool,” said Petro. “One thing its instruments have allowed us to do is peer back in time at the forces that shaped the Moon; as we can see with the asteroid impact revelation, this has led to groundbreaking discoveries that have changed our view of Earth.”

The Moon as Earth’s Mirror

LRO’s thermal radiometer, called Diviner, has taught scientists how much heat is radiating off the Moon’s surface, a critical factor in determining crater ages. By looking at this radiated heat during the lunar night, scientists can calculate how much of the surface is covered by large, warm rocks, versus cooler, fine-grained regolith, also known as lunar soil.

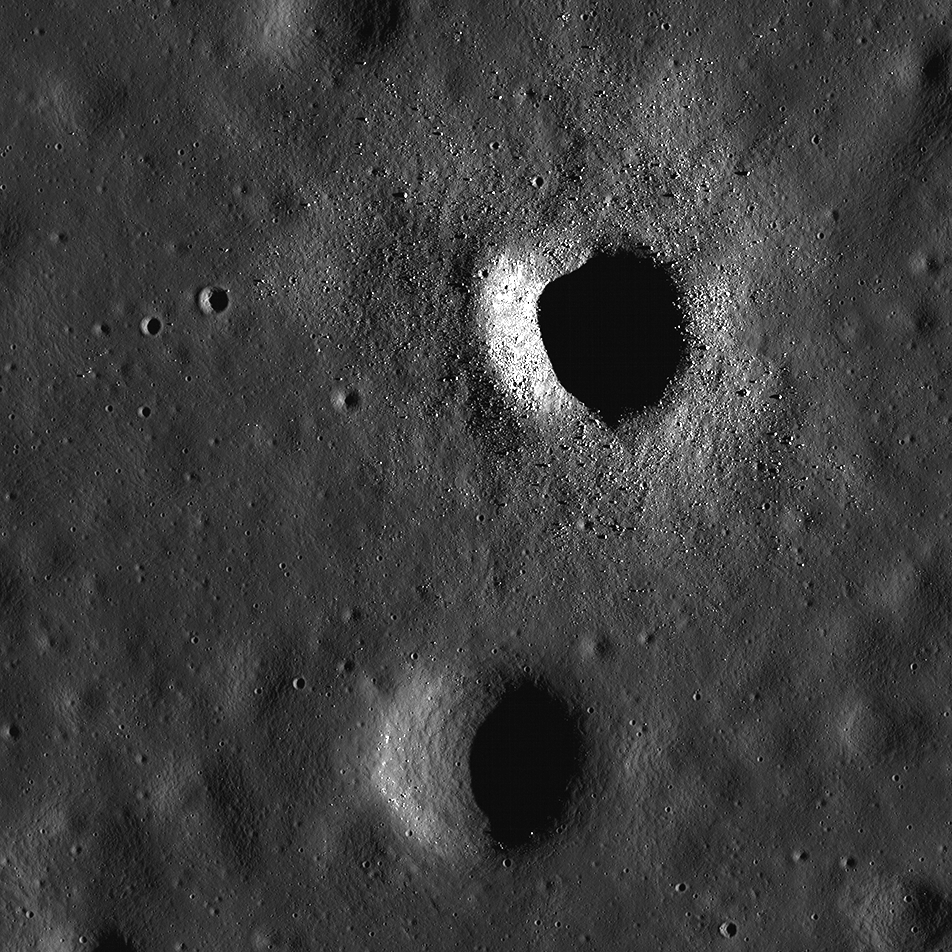

Large craters formed by asteroid impacts in the last billion years are covered by boulders and rocks, while older craters have few rocks, Diviner data showed. This happens because impacts excavate lunar boulders that are ground into soil over tens to hundreds of millions of years by a constant rain of tiny meteorites.

Paper co-author Rebecca Ghent, a planetary scientist at University of Toronto and the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, calculated in 2014 the rate at which Moon rocks break down into soil. Her work thus revealed a relationship between an abundance of large rocks near a crater and the crater’s age. Using Ghent’s technique, the team assembled a list of ages of all lunar craters younger than about a billion years.

“It was a painstaking task, at first, to look through all of these data and map the craters out without knowing whether we would get anywhere or not,” said Sara Mazrouei, the lead author of the Science paper who collected and analyzed all the data for this project while a Ph.D. student at the University of Toronto.

The work paid off, returning several unexpected findings. First, the team discovered that the rate of large crater formation on the Moon has been two to three times higher over approximately the last 290 million years than it had been over the previous 700 million years. The reason for this jump in the impact rate is unknown. It might be related to large collisions taking place more than 300 million years ago in the main asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, the researchers noted. Such events can create debris that can reach the inner solar system.

The second surprise came from comparing the ages of large craters on the Moon to those on Earth. Their similar number and ages challenges the theory that Earth had lost so many craters through erosion that an impact rate could not be calculated.

“The Earth has fewer older craters on its most stable regions not because of erosion, but because the impact rate was lower about 290 million years ago,” said William Bottke, an asteroid expert at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado and a co-author of the paper. “This meant the answer to Earth’s impact rate was staring everyone right in the face.”

Credits: Ernie Wright & David Ladd/NASA Goddard

Proving that fewer craters meant fewer impacts—rather than loss through erosion—posed a formidable challenge. Yet the scientists found strong supporting evidence for their findings through a collaboration with Thomas Gernon, an Earth scientist based at the University of Southampton in England who works on a terrestrial feature called kimberlite pipes.

These underground pipes are long-extinct volcanoes that stretch, in a carrot shape, a couple of kilometers below the surface. Scientists know a lot about the ages and rate of erosion of kimberlite pipes because they are widely mined for diamonds. They also are located on some of the least eroded regions of Earth, the same places we find preserved impact craters.

Gernon showed that kimberlite pipes formed since about 650 million years ago had not experienced much erosion, indicating that the large impact craters younger than this on stable terrains must also be intact. “So that’s how we know those craters represent a near-complete record,” Ghent said.

Ghent’s team, which also included Southwest Research Institute planetary astronomer Alex Parker, wasn’t the first to propose that the rate of asteroid strikes to Earth has fluctuated over the past billion years. But it was the first to show it statistically and to quantify the rate. Now the team’s technique can be used to study the surfaces of other planets to find out if they might also show more impacts.

The team’s findings related to Earth, meanwhile, may have implications for the history of life, which is punctuated by extinction events and rapid evolution of new species. Though the forces driving these events are complicated and may include other geologic causes, such as large volcanic eruptions, combined with biological factors, the team points out that asteroid impacts have surely played a role in this ongoing saga. The question is whether the predicted change in asteroid impacts can be directly linked to events that occurred long ago on Earth.

This research was funded in part by NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute (SSERVI). Researchers at the Southwest Research Institute are part of 13 teams within SSERVI, based and managed at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. SSERVI is funded by the Science Mission Directorate and Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. For more about SSERVI visit: sservi.nasa.gov.

By Lonnie Shekhtman

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.