NASA’s twin E-TBEx CubeSats — short for Enhanced Tandem Beacon Experiment — are scheduled to launch in June 2019 aboard the Department of Defense’s Space Test Program-2 launch. The launch includes a total of 24 satellites from government and research institutions. They will launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy from historic Launch Complex 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

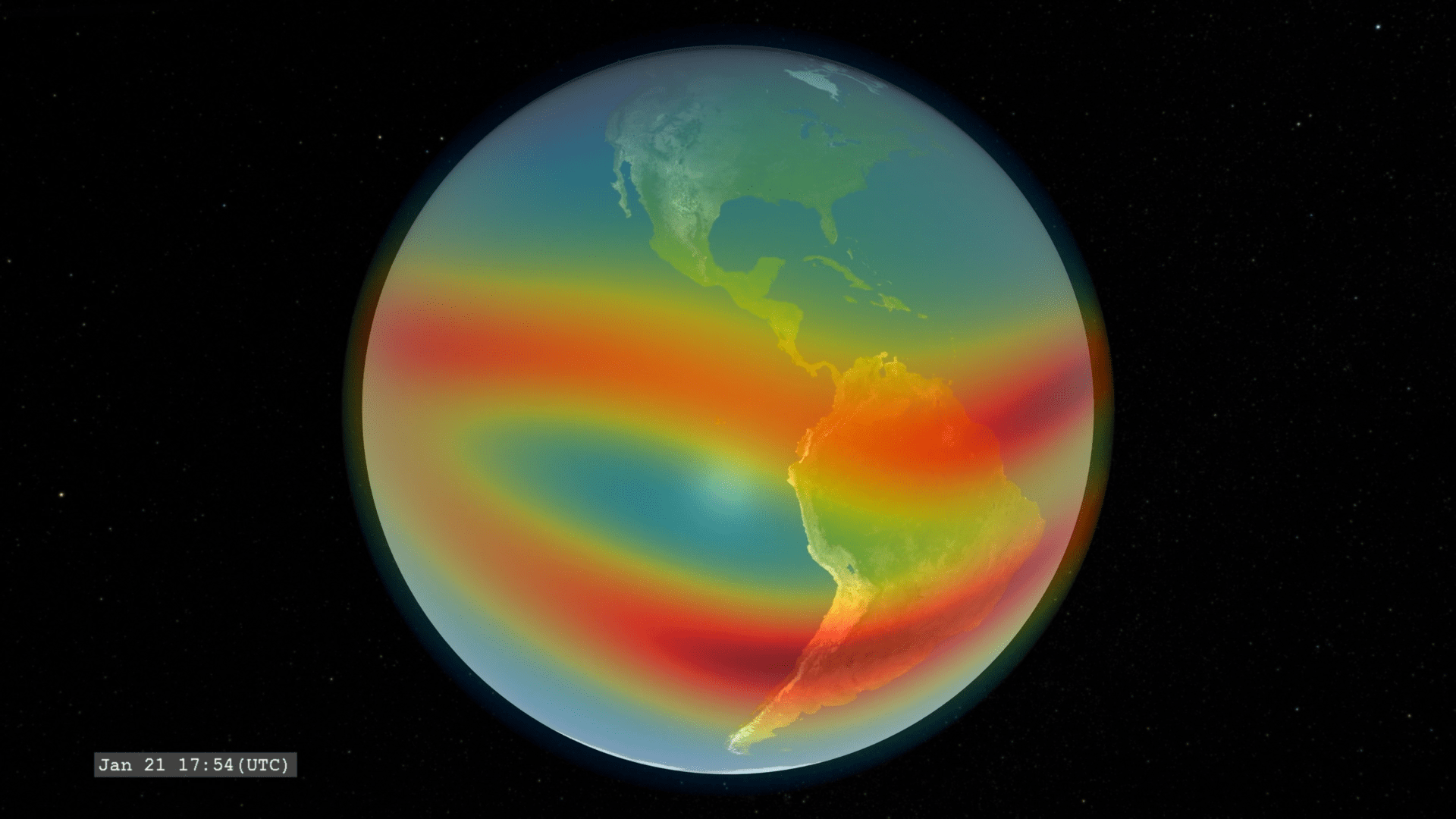

The E-TBEx CubeSats focus on how radio signals that pass through Earth’s upper atmosphere can be distorted by structured bubbles in this region, called the ionosphere. Especially problematic over the equator, these distortions can interfere with military and airline communications as well as GPS signals. The more we can learn about how these bubbles evolve, the more we can mitigate those problems — but right now, scientists can’t predict when these bubbles will form or how they’ll change over time.

“These bubbles are difficult to study from the ground,” said Rick Doe, payload program manager for the E-TBEx mission at SRI International in Menlo Park, California. “If you see the bubbles start to form, they then move. We’re studying the evolution of these features before they begin to distort the radio waves going through the ionosphere to better understand the underlying physics.”

The ionosphere is the part of Earth’s upper atmosphere where particles are ionized — meaning they’re separated out into a sea of positive and negative particles, called plasma. The plasma of the ionosphere is mixed in with neutral gases, like the air we breathe, so Earth’s upper atmosphere — and the bubbles that form there — respond to a complicated mix of factors.

Because its particles have electric charge, the plasma in this region responds to electric and magnetic fields. This makes the ionosphere responsive to space weather: conditions in space, including changing electric and magnetic fields, often influenced by the Sun’s activity. Scientists also think that pressure waves launched by large storm systems can propagate up into the upper atmosphere, creating winds that shape how the bubbles move and change. This means the ionosphere — and the bubbles — are shaped by terrestrial weather and space weather alike.

The E-TBEx CubeSats send radio beacon signals at three frequencies — close to those used by communications and GPS satellites — to receiving stations on the ground, at which point scientists can detect minute changes in the signals’ phase or amplitude. Those disruptions can then be mapped back to the region of the ionosphere through which they passed, giving scientists information about just how these bubbles form and evolve.

“All signals are created at the same time — with the same phase — so you can tell how they get distorted in passing through the bubbles,” said Doe. “Then, by looking at the distortions, you can back out information about the amount of roughness and the density in the bubbles.”

The data produced by the twin CubeSats is complemented by similar beacons onboard NOAA’s six COSMIC-2 satellites. Like the E-TBEx CubeSats, the COSMIC-2 beacons send signals at three frequencies — slightly different than those used by E-TBEx — to receiving stations on the ground. The combination of measurements from all eight satellites will give scientists chances to study some of these bubbles from multiple angles at the same time.

E-TBEx’s beacon was built by a team at SRI International, which also designed and fabricated the beacons on COMSIC-2. The E-TBEx CubeSats were developed with Michigan Exploration Lab at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. The design, fabrication, integration and testing was carried out mostly by teams of undergraduate and graduate students.

“Building and testing E-TBEx was pretty complex because of the number of deployable parts,” said James Cutler, an aerospace engineering professor at University of Michigan who led the student teams that worked on E-TBEx. “The payload is essentially a flying radio station, so we have five antennas to deploy — four with two segments each — and, also, four solar panels.”

What scientists learn from E-TBEx could help develop strategies to avoid signal distortion — for instance, allowing airlines to choose a frequency less susceptible to disruption, or letting the military delay a key operation until a potentially disruptive ionospheric bubble has passed.

STP-2 is managed by the U.S. Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center. The Department of Defense mission will demonstrate the capabilities of the Falcon Heavy rocket while delivering satellites to multiple orbits around Earth over the course of about six hours. These satellites include three additional NASA projects to improve future spacecraft design and performance.

By Sarah Frazier

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.