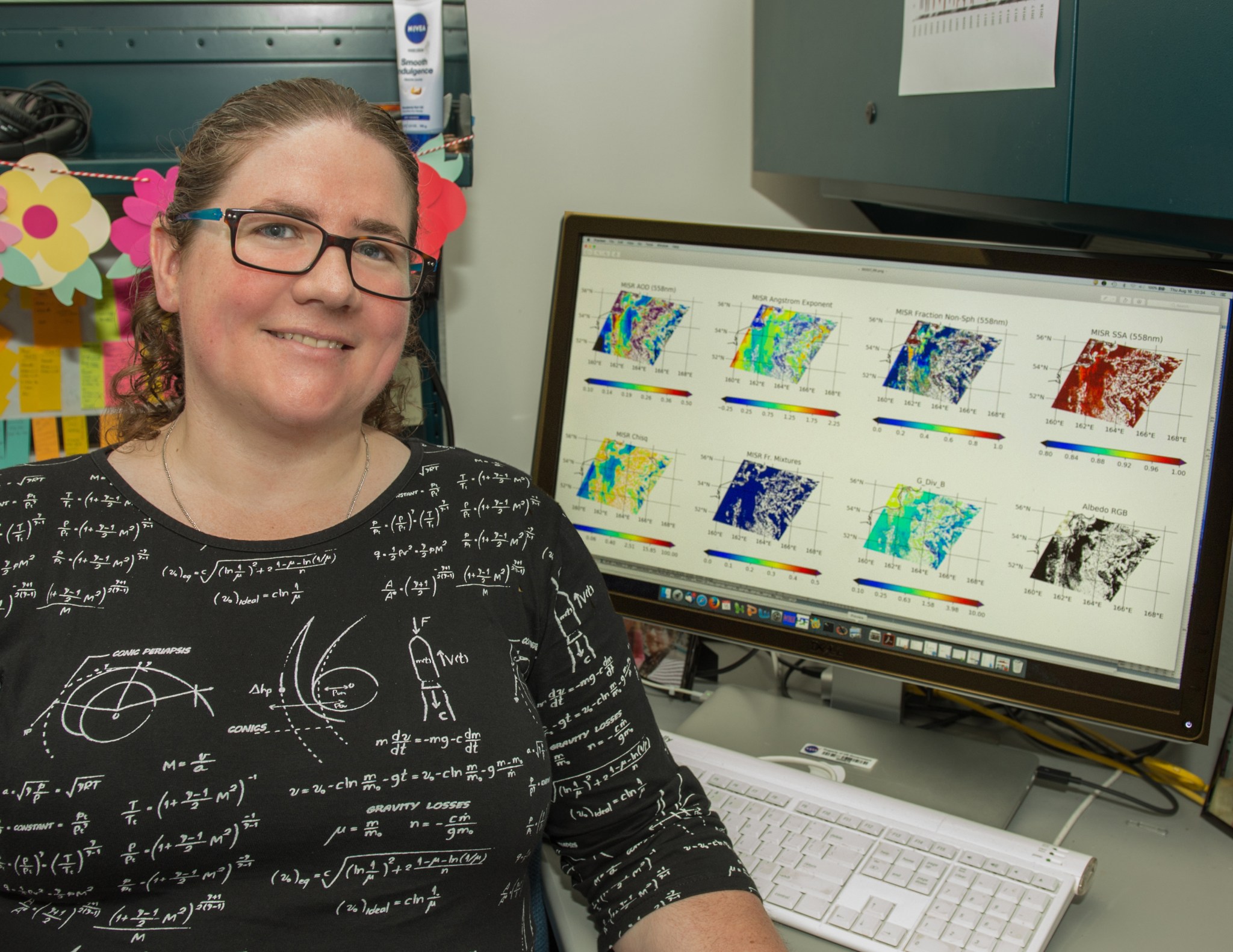

Name: Verity J. Flower

Title: Post-Doctoral Fellow

Organization: Code 613, Climate and Radiation Lab, Science Mission Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I’m the resident volcanologist in our lab. I use satellite data to study volcanic eruptions. Specifically, I use data from the Multi-angle Imaging Spectroradiometer (MISR) satellite to analyze volcanic eruption plume height and particle properties within the plumes. When volcanoes erupt, the processes underground that caused the eruption can produce different particles, including ash and gas. We track these different particles to understand what caused the eruption. We are trying to assess how they change over time to help us understand how the system works.

How did someone who grew up in the English Midlands, where there are no volcanoes, become a volcanologist?

I was born and raised in the English countryside somewhere between Oxford and Cambridge. This area of the country has lovely, rolling hills, which I still miss. No volcanoes in sight.

When I was 5, our family went on holiday to Tenerife in the Canary Islands. My older brother had just learned about volcanoes in school, including the difference between dormant and extinct, which is very important. He proceeded to tell me that Teide, the volcano on Tenerife, was dormant and could erupt at any moment. I could not sleep for most of the holiday. My mum said that ever since then, I’ve been obsessed with understanding volcanoes. I remember being fascinated by volcanoes from that point forward. So I became a volcanologist.

Where did you study to become a volcanologist?

Growing up, everyone (besides my mum) discouraged me from studying volcanology because there were so few jobs in the field. My undergraduate degree from Portsmouth University, UK, is in environmental science specializing in natural hazards, which covered volcanology, earthquakes, flooding and defenses against all of these hazards. My master’s degree from Birmingham University, UK, is in atmospheric sciences focusing on volcanic plumes. With my unique combination of volcanics and atmospheric science, I was accepted into a doctoral program at Michigan Technological University in Houghton to study volcanic remote sensing.

What was your favorite field campaign?

In 2012, I went on a field campaign to Costa Rica to study volcanic plumes with instruments that calculate the types and amounts of gases contained within the plumes. We spent two weeks at a lodge one mile from an active volcano called Turrialba. Every day we woke up to plumes from the volcano. It was fun.

It is fascinating to watch the plumes disperse and look at their interaction with the atmosphere. Despite being in an exclusion zone, we were permitted to work on the volcano. We worked with local scientists and were allowed to take measurements from the summit’s edge and also into the active plume. I even got to stand on top of the volcano about 100 yards from the active vent. There were active plumes, but no lava.

We wore gas masks and protective clothing. Plus we were all very, very careful.

Although I haven’t been on any more recent field campaigns, volcanologists tend to hold conferences near active volcanoes. I have been to Sakurjima, Japan; Merapi, Indonesia; Eyjafjallajokull, Iceland, the site of the 2010 eruption; and Vesuvius, Italy. Each conference includes a field trip to sites of interest including the local active volcano.

What is most dangerous about working near an active volcano?

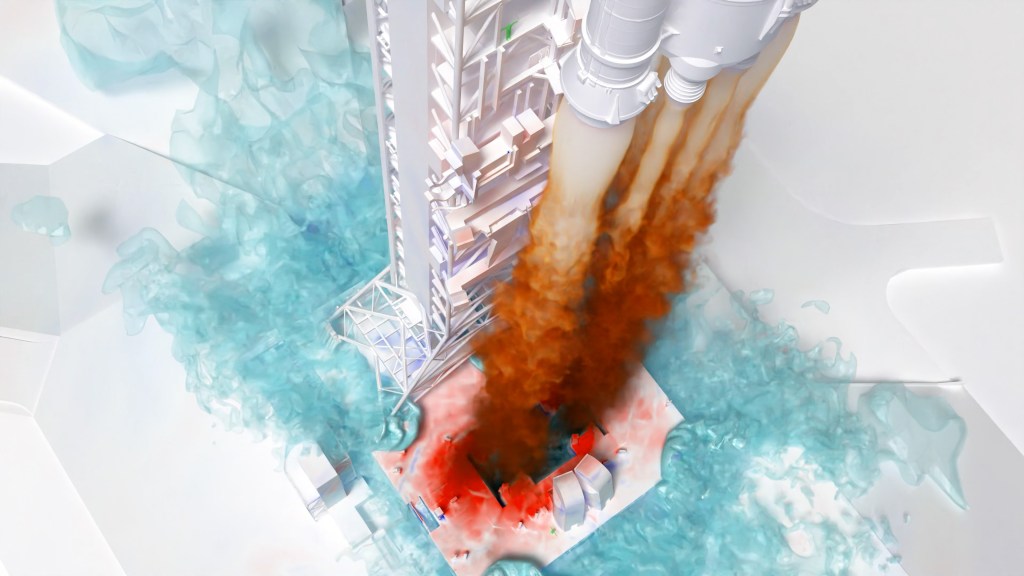

While lava looks spectacular and can do a lot of damage, it is generally slow moving enough that it is usually possible to evacuate an area before the lava takes over. With lava, the area to avoid is near the actual vent due to possible projectile pieces of molten rock. Another area to avoid with lava is where the lava enters the ocean because the temperature difference can cause rapid cooling and the resultant pressure changes can create hot explosions and toxic fumes.

Plumes are actually the most dangerous product of volcanic eruptions. Plumes are made out of gas, rock fragments and super-heated water vapor. Plumes can be emitted high into the air and then drop all these components down onto the ground, which can kill people, livestock and crops. Plumes can also be emitted close to the ground, possibly with catastrophic consequences. Pompeii’s people were instantly wiped out from ground plumes’ particles and gases, not lava. By way of very loose analogy, it is like being dropped into boiling water.

Lava flows look so spectacular. But it is the plume that is generally more deadly.

What would you say to someone who wanted to study science?

I went a round about way to get exactly where I wanted to be. I tell students to take what they have learned and apply it to what they want to study, even if it is in a different subject area. Whatever your interest, keep your options open. Sometimes studying an unrelated area actually provides insight and a new perspective. There are a lot of volcanologists. My atmospheric background gives me the ability to link the dynamics of plume dispersion to both the volcanic mechanisms and the atmospheric impact. Try to bring your unique perspective to whatever you are interested in and remain open to other areas.

What makes a good scientist?

Be curious. Investigate. If something interests you, find out everything you can about it. Ask questions. Observe. Solicit opinions from experts in the field. Keep learning and studying.

How does it feel to grow up in rural England and now live in a city near the capital of the U.S.?

Growing up in the English countryside, I was used to making my own entertainment by reading, sewing and exploring. Now, living in a city near the U.S. capital, I have access to museums and theaters, and I go as much as I can. I still sew and read. I don’t have a car here, so I take two subway trains and one bus to work. I am able to read about one book, especially mysteries and thrillers, every day on my commute. I miss my family, who are all in England.

Has anyone at Goddard inspired and helped you?

For the first time in my career, I am fortunate enough to have a mentor, my supervisor, Ralph Kahn. In Ralph, I have found a kindred spirit in applying the scientific process. We are able to communicate our ideas easily and I greatly value his opinion. Through his guidance, Ralph has helped me develop my research in ways that I would not have thought of by myself. Ralph makes me think. He has a way of shifting my perspective to allow me to see more nuances in the problems at hand.

Is there something surprising about your hobbies that people do not generally know?

Sometime in the future, I would like to have a small cottage near rolling hills with a small, wildflower garden. I would also like to have Labrador retrievers.

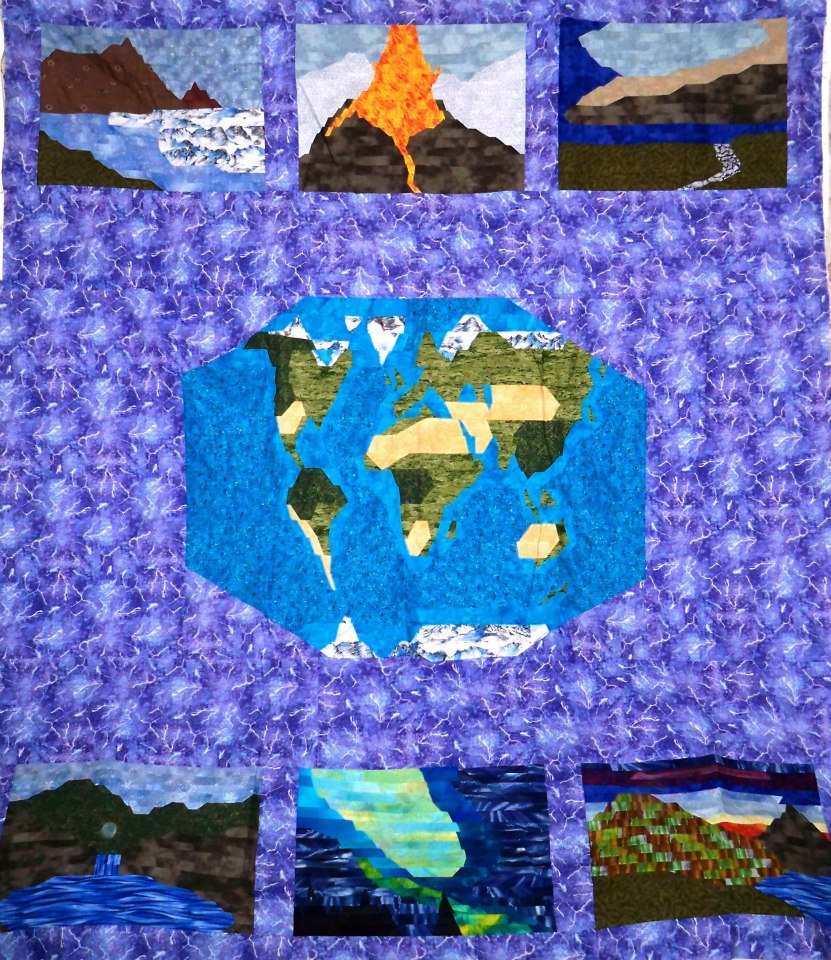

For now, I make patchwork quilts. I have been making patchwork quilts since I was 4. I spent most holidays with my grandparents and my grandmother, a seamstress, taught me. She had no daughters and I was one of only two granddaughters, so she passed on her knowledge to me.

I started quilting using sewing machines. Recently, I began doing everything by hand. I made a quilt showing my love of nature, and it has a map of the world with panels of volcanic eruptions, a lightning storm, glaciers and other natural phenomena.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center