A compact detector technology applicable to all types of cross-disciplinary scientific investigations has found a home on a new CubeSat mission designed to find the electromagnetic counterparts of events that generate gravitational waves.

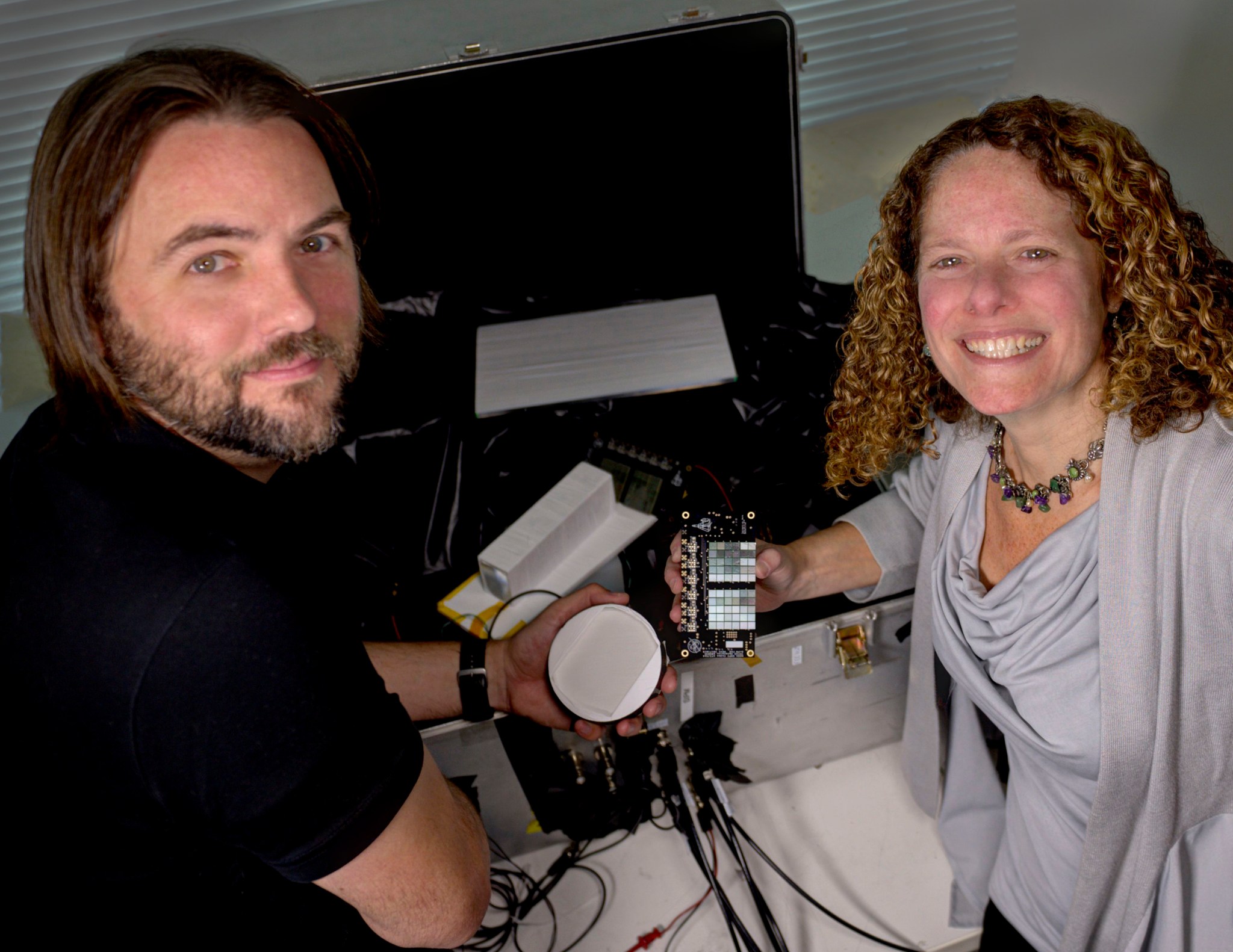

NASA scientist Georgia de Nolfo and her collaborator, astrophysicist Jeremy Perkins, recently received funding from the agency’s Astrophysics Research and Analysis Program to develop a CubeSat mission called BurstCube. This mission, which will carry the compact sensor technology that de Nolfo developed, will detect and localize gamma-ray bursts caused by the collapse of massive stars and mergers of orbiting neutron stars. It also will detect solar flares and other high-energy transients once it’s deployed into low-Earth orbit in the early 2020s.

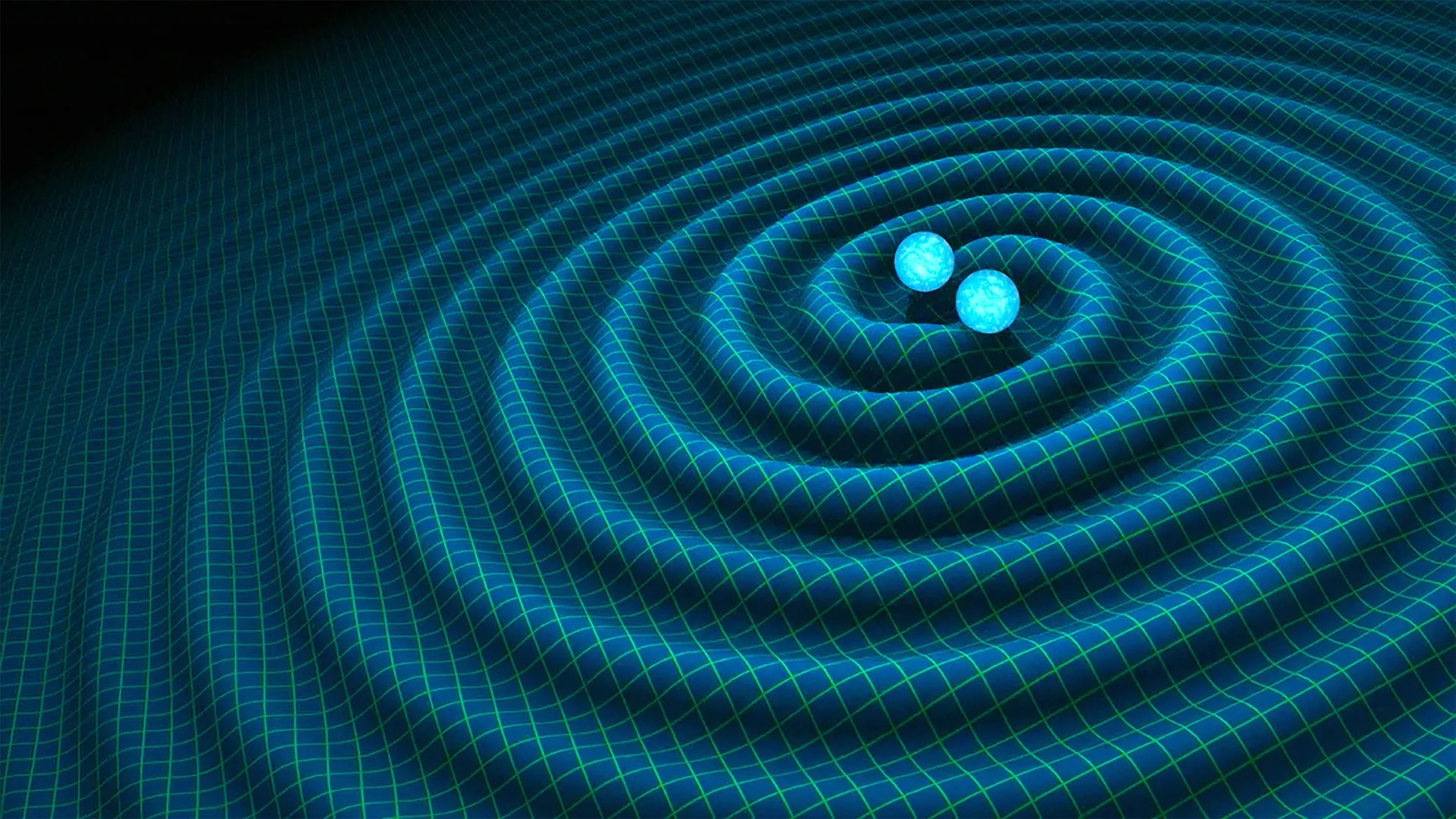

The cataclysmic deaths of massive stars and mergers of neutron stars are of special interest to scientists because they produce gravitational waves — literally, ripples in the fabric of space-time that radiate out in all directions, much like what happens when a stone is thrown into a pond.

Since the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory, or LIGO, confirmed their existence a couple years ago, LIGO and the European Virgo detectors have detected other events, including the first-ever detection of gravitational waves from the merger of two neutron stars announced in October 2017.

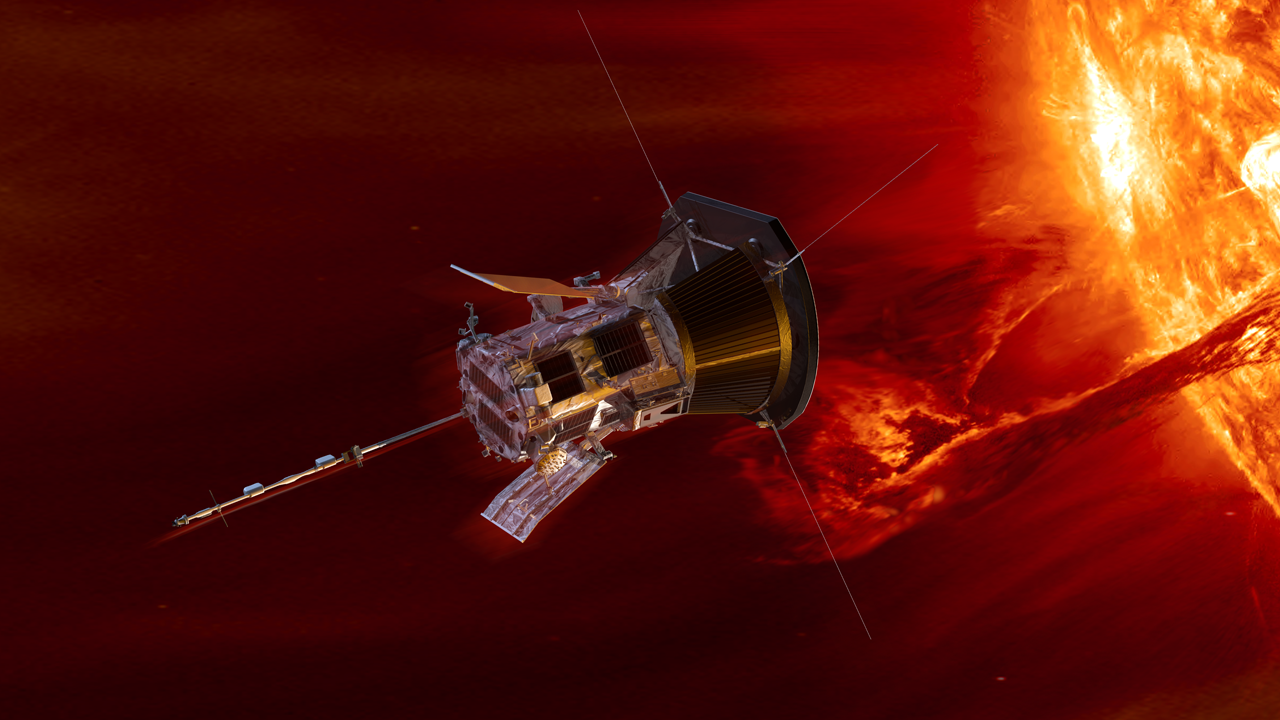

Less than two seconds after LIGO detected the waves washing over Earth’s space-time, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected a weak burst of high-energy light — the first burst to be unambiguously connected to a gravitational-wave source.

These detections have opened a new window on the universe, giving scientists a more complete view of these events that complements knowledge obtained through traditional observational techniques, which rely on detecting electromagnetic radiation — light — in all its forms.

Complementary Capability

Perkins and de Nolfo, both scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, see BurstCube as a companion to Fermi in this search for gravitational-wave sources. Though not as capable as the much larger Gamma-ray Burst Monitor, or GBM, on Fermi, BurstCube will increase coverage of the sky. Fermi-GBM observes the entire sky not blocked by the Earth. “But what happens if an event occurs and Fermi is on the other side of Earth, which is blocking its view,” Perkins said. “Fermi won’t see the burst.”

BurstCube, which is expected to launch around the time additional ground-based LIGO-type observatories begin operations, will assist in detecting these fleeting, hard-to-capture high-energy photons and help determine where they originated. In addition to quickly reporting their locations to the ground so that other telescopes can find the event in other wavelengths and home in on its host galaxy, BurstCube’s other job is to study the sources themselves.

Miniaturized Technology

BurstCube will use the same detector technology as Fermi’s GBM; however, with important differences.

Under the concept de Nolfo has advanced through Goddard’s Internal Research and Development program funding, the team will position four blocks of cesium-iodide crystals, operating as scintillators, in different orientations within the spacecraft. When an incoming gamma ray strikes one of the crystals, it will absorb the energy and luminesce, converting that energy into optical light.

Four arrays of silicon photomultipliers and their associated read-out devices each sit behind the four crystals. The photomultipliers convert the light into an electrical pulse and then amplify this signal by creating an avalanche of electrons. This multiplying effect makes the detector far more sensitive to this faint and fleeting gamma rays.

Unlike the photomultipliers on Fermi’s GBM, which are bulky and resemble old-fashioned television tubes, de Nolfo’s devices are made of silicon, a semiconductor material. “Compared with more conventional photomultiplier tubes, silicon photomultipliers significantly reduce mass, volume, power and cost,” Perkins said. “The combination of the crystals and new readout devices makes it possible to consider a compact, low-power instrument that is readily deployable on a CubeSat platform.”

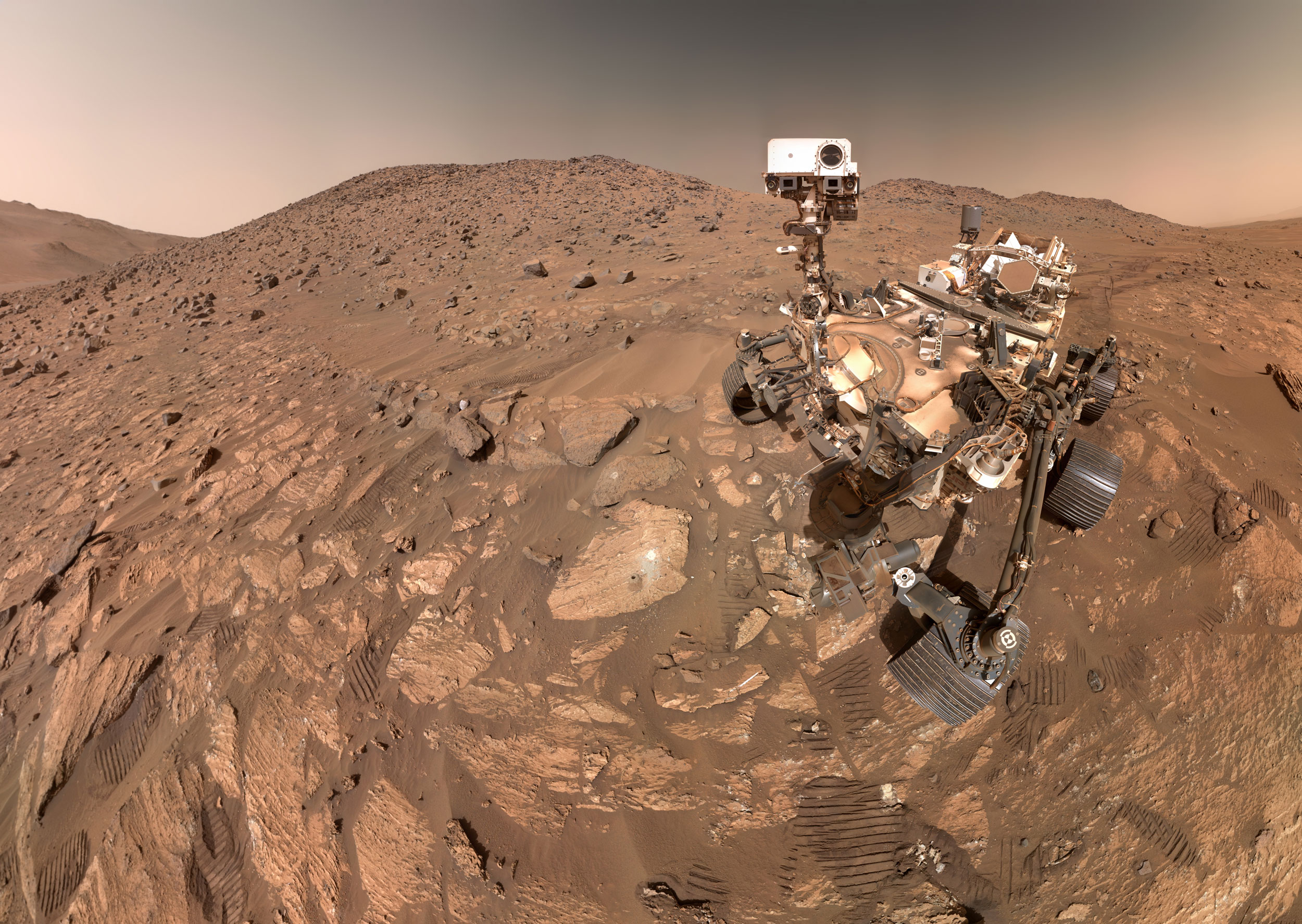

In another success for Goddard technology, the BurstCube team also has baselined the Dellingr 6U CubeSat bus that a small team of center scientists and engineers developed to show that CubeSat platforms could be more reliable and capable of gathering highly robust scientific data.

“This is high-demand technology,” de Nolfo said. “There are applications everywhere.”

For other Goddard technology news, go to https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/winter_2018_final_lowrez.pdf?emrc=640796

By Lori Keesey

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center