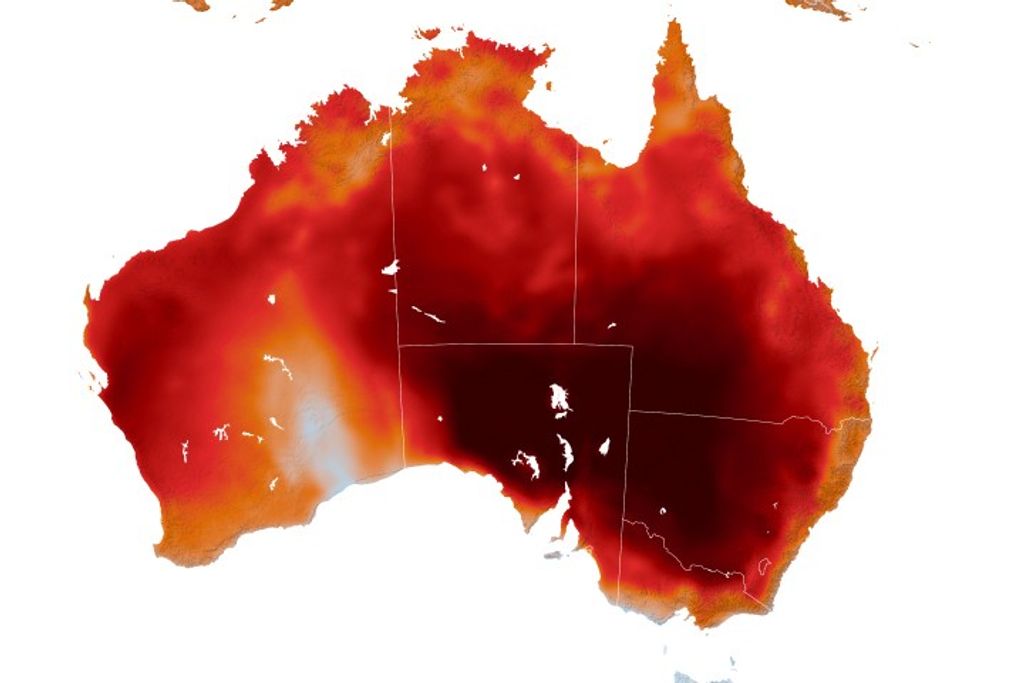

There is no shortage of eyeballs, human and robotic, pointed at Mars. Scientists are constantly exploring the Red Planet from telescopes on Earth, plus the six spacecraft circling the planet from its orbit, and two roving its surface. So when dust filled the atmosphere during the recent planet-wide dust storm, observations were plentiful.

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) provided the earliest insights on May 30 when it observed an accumulation of dust in the atmosphere near Perseverance Valley, where NASA’s Opportunity rover is exploring. The increasingly hazy storm, the biggest since 2007, forced Opportunity to shut down science operations by June 8, given that sunlight couldn’t penetrate the dust to power the rover’s solar panels. Scientists are anxiously waiting for the roving explorer to regain power and phone home.

Meanwhile, on June 5, evidence quietly materialized on the other side of the globe that the storm was growing and beginning to affect Gale Crater, the research site of NASA’s Curiosity rover. (The storm was officially classified as global on June 20.)

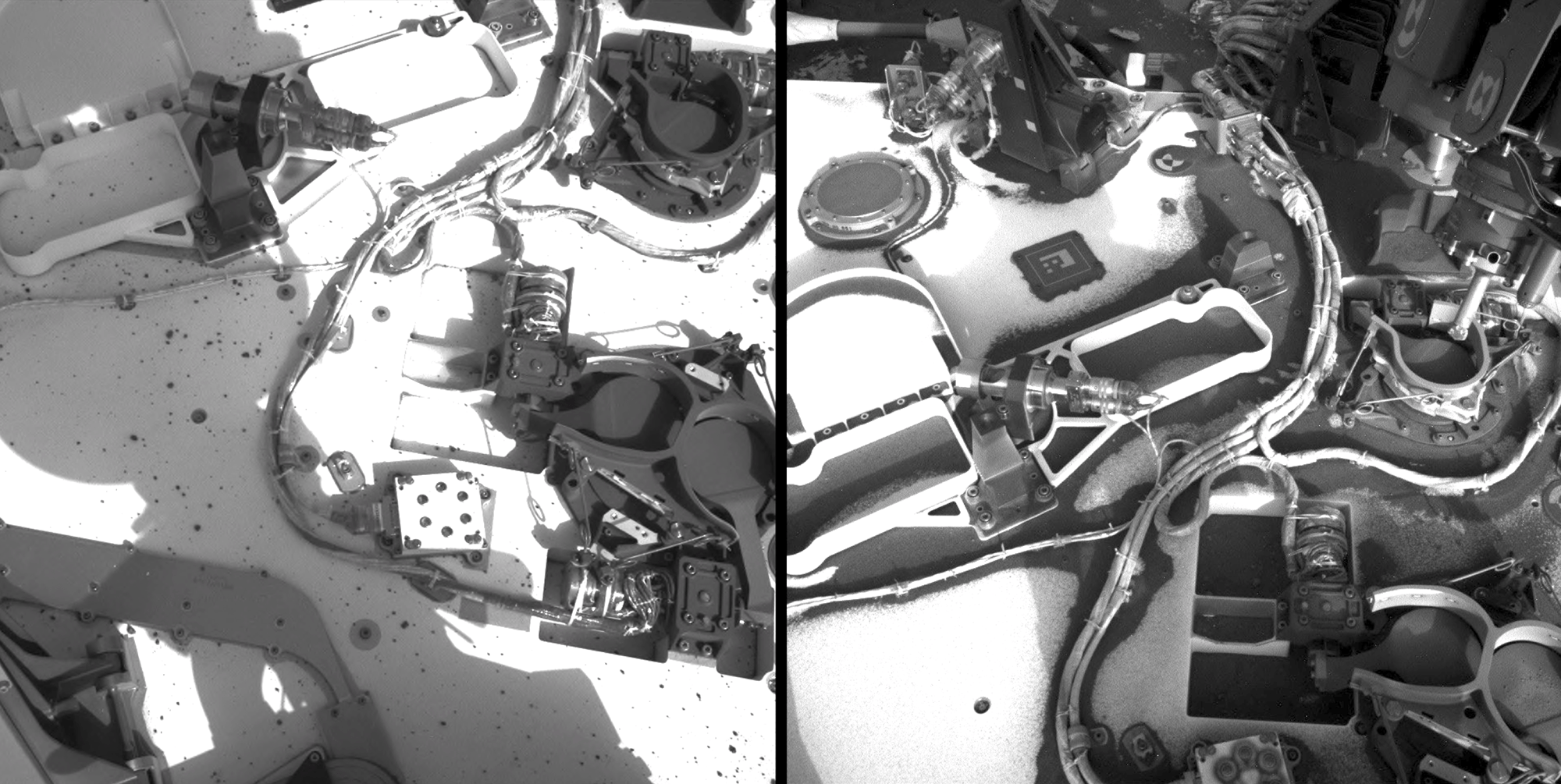

It came from an unexpected source: an actuator, or motor, that powers a lid to a funnel that takes in samples of powdered Martian rock dropped in by Curiosity’s drill. The samples then undergo chemical analysis by the portable Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) chemistry lab, designed by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and built into Curiosity’s belly.

Benito Prats, a Goddard electromechanical engineer, noticed the dust storm slowly reaching Curiosity through the continuous temperature readings he collected from actuator sensors.

“All my charts showed the dust storm effect on the actuator because it’s exposed; it’s sitting out there on the rover deck,” said Prats. “All of a sudden, I saw the daytime temperature drop really quickly.”

At night, too, said Prats, he saw temperatures rising above normal levels. This happens during a dust storm because less sun penetrates the dusty atmosphere during the day, cooling the surface of the planet, while at night, the warmer, dusty atmosphere heats the ground. Other weather tools on the explorer, such as the Rover Environmental Monitoring Station, which measures air temperature, atmospheric pressure, and other environmental conditions, were also beginning to indicate accumulating dust.

Unlike solar-powered Opportunity, Curiosity is powered by a plutonium generator, so its operations were not affected by the dust shade. The temperature changes also didn’t affect SAM actuators — there are two sample funnels, in case one gets clogged — since they like warmer, less extreme temperatures.

SAM analyzes Martian rocks and soils in search of organic materials. In order for SAM to work properly, its actuators need to be at minus 40 degrees Celsius (minus 40 Fahrenheit). This is why Prats keeps a close eye on their temperature. When Martian temperatures in spring dip to minus 60 degrees Celsius (minus 76 Fahrenheit) at night, SAM heaters must warm up the motors to lift the funnel lid for sample drops.

Credits: NASA/Benito Prats/Molly Wasser

After Prats discovered the effects of the dust storm in his temperature data, he combined it with historic actuator temperature averages to estimate when the dust storm would abate.

“At sol 2,125 (July 28), I noticed a linear trend,” he said, “so I said OK, I can predict that sol 2,180 (Sept. 23) is going to be when we’re going to get out of the dust storm and the temperature will return back to normal, though I later updated that to sol 2,175 (Sept. 18).” His prediction was consistent with more formal ones, and matches recent actuator temperature readings, which were back to normal around Sept. 18, indicating that the dust over Gale Crater had settled by then. A majority of the dust also has settled at Perseverance Valley.

Data from any source, even the most unexpected, are useful to planetary scientists, given we still don’t know why some Martian dust storms last for months and grow massive, while others stay small and last only a week.

Scientists hope to be able to forecast these global events, like they can forecast hurricanes on Earth, in order to better understand the planet’s current and past climate and to properly design robotic and human missions to the planet, NASA scientists say.

“There are some things about Mars that make it more predictable and some that make it less so than Earth,” said Scott D. Guzewich, a Goddard atmospheric scientist leading Curiosity’s dust storm investigation.

“I can estimate, two years in advance, the temperature, air pressure, and whether there’s going to be dust or clouds in the air during the non-dusty season anywhere on the planet,” he said. “But during the dusty season, in locations that have dust storms, I can’t give you any prediction at all that there will be a dust storm on one day and not another.”

By Lonnie Shekhtman

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.