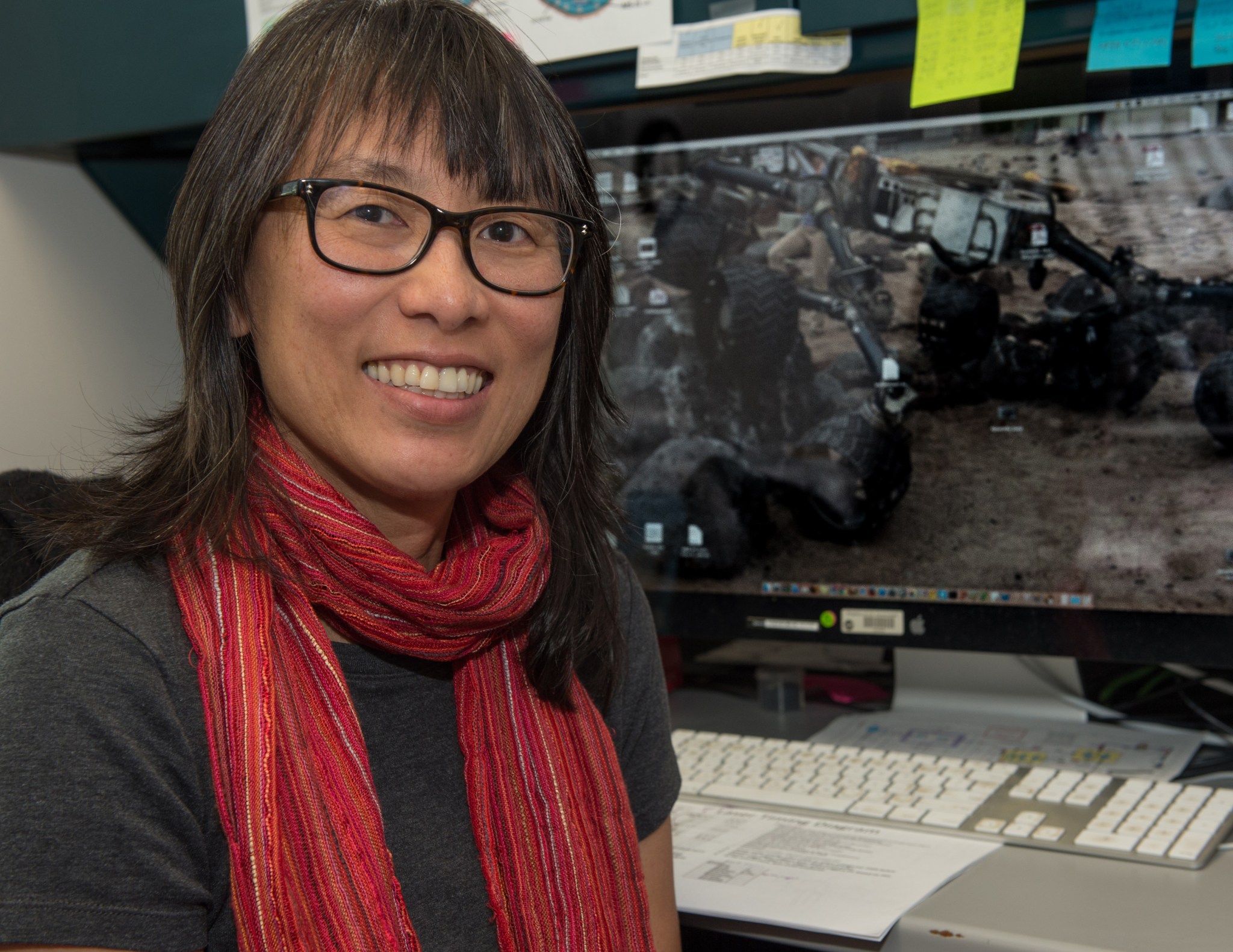

Name: Florence Tan

Formal Job Classification: Electrical engineer

Organization: Code 565, Avionics and Electrical Systems Branch, Electrical Engineering Division, Applied Engineering and Technology Directorate, Office of the Director (Currently on detail at NASA Headquarters.)

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I build electronics for mass spectrometers at Goddard. A mass spectrometer is like a nose. It sniffs out the constituent components of a gaseous sample, which could be the atmosphere of, say, Mars or Titan, or a pyrolyzed soil sample, meaning one that has been heated up to 1,100 C (2,012 F).

I was the product design lead for Mars Science Laboratory Sample Analysis at Mars, Exo-Mars Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer, Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission Neutral Gas and Ion Mass Spectrometer instrument, and Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer Neutral Mass Spectrometer. All of these instruments are mass spectrometer payloads on orbiters or Mars rovers.

I also designed electronics and wrote software for the Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer on the orbiter and the Gas Chromatograph and Mass Spectrometer on the Huygens Probe into Titan, a moon of Saturn. I have also built electronics and written software for other mass spectrometers.

Please describe your electrical lab.

Our lab has benches with equipment such as power supplies, oscilloscopes, logic analyzers, digital voltmeters, computers, customized equipment, as well as commercial off the shelf equipment to measure electrical signals. This equipment helps us work with whatever device we are testing. We have computers to take and display data from the device under test. We also have electronics rework stations with soldering irons, fans, lights and high-magnification lamps.

In our labs, we take precautions to prevent electrostatic discharge (ESD). We have anti-static mats and we wear protective garments with conductive filaments. We use active monitoring conductive wrist straps to prevent charge build up. We also have ion generators and humidity control. Humid conditions prevent ESD generation because the moisture allows electric charges to dissipate.

What did you want to be when you were a child in Malaysia?

Growing up in a small, coastal fishing village in Malaysia, I wanted to be a teacher. I did not have very many role models. My parents were teachers and they encouraged me to be more successful than they were, so I wanted to be a professor. Later, after I watched a few reruns of “Star Trek,” I decided I wanted to be an aerospace or electrical engineer.

What was the impact of the Japanese invasion of Malaysia (Malaya, at the time) during World War II on your parents and how does your family background influence you?

To know me is to know my family background and how the Japanese invasion during World War II impacted my parents and later us. My grandfather died when my father was 2. My father was one of 13 children, so he started life facing a lot of challenges.

When he was nine, World War II came to his door step. According to my father, the first wave of Japanese invaders came on bicycles carrying guns with bayonets. Rather than waste a bullet, the invaders bayoneted people in the stomach causing a long, suffering death by infection. The second wave of invaders, which came after the general population was already terrorized and subdued, were the administrators.

My parents and their families ran into the jungle and hid. If people happened to be in the wrong place, they were slaughtered. One river up from my father’s village, the entire village was slaughtered. My father saw lots of horrifying things. He saw people die, including his childhood friend who was only 9 years old. The neighboring village became a place of death. I heard many stories from my parents and grandparents about the cruelty of the soldiers. If someone were disrespectful, for example by failing to immediately bow to a soldier he encountered, he could be killed.

One of my aunts cut off her hair and dressed like a young boy to avoid being taken away by the invaders to serve as a “comfort woman.” One of my mother’s uncles was water-tortured, then hung upside down for a month. He survived, but he suffered for the rest of his life.

It was a time of great tribulation for all of Malaya.

My father’s family farmed. During the war, they also became fishermen and ate edible tree roots to survive.

The Japanese Occupation of Malaya ended three years and eight months after it started. The occupation seemed so very long to those living it. To this day, we have a local Hokkien saying, “three years and eight months,” which means “a very long time,” as in, “Do you want me wait three years and eight months?”

After World War II, the infrastructure in Malaya was poor. Despite these setbacks, when my father was 13 at the end of the war, he was sent to fourth grade. Within six months, he was in the sixth grade. He and his classmates could barely read or write. Most dropped out. But my father graduated from high school. After he graduated, a neighbor told my grandmother, “Your son graduating from high school is worth 200 acres of rubber plantation.” To us at that time, this meant a lot of money and was an enormous compliment. He then went to a local teacher training school and became a teacher.

My mother had a more fortunate upbringing. She was younger by three years, so she was 6 when the war came and was less impacted by the war. When the war ended, she started in third grade and began learning to read and write.

How did your parents guide and educate you and your three siblings?

My father grew up to be very frugal. My parents had four children, two girls followed by two boys. I am No. 2.

My parents had a really wonderful plan, something very commonplace in our culture. They understood that education was the way to a better life for everyone. Ever since I was little, my parents said that they had enough money to pay to educate two of their children. Their plan was that the first two children, my sister and I, would go to school, graduate and then get jobs to help pay for my two younger brothers to also go to school.

When I graduated from college, my friends got cars. I pooled my funds with those of my family so that my two brothers could go to college.

All of us have done well, thanks to our parents.

My parents did their best and guided us very well. Their life experiences shaped our lives. They did not go to college. They watched their former students come back with college degrees and immediately earn twice what they earned, without any experience. My parents always insisted that the four of us get college degrees.

My family story is very typical of my Malaysian contemporaries.

My parents saved money every way they could. My father once wore out a pair of shoes and kept walking in them even though they had holes. I watched him put in pieces of cardboard to cover the holes in the soles. Years later when I earned my first paycheck, I bought him a pair of Christian Dior shoes from the U.S. and sent them to Malaysia. They were a size too small, but he appreciated them anyway.

Have you passed on your parents’ lessons to your children?

My husband and I have two daughters. Both of our daughters are in college and doing well. They learned a lot from their grandparents and understand the importance of education and family.

When did you leave Malaysia?

I left Malaysia when I was almost 18 to go to Western Michigan University and, after one year, transferred to the University of Maryland, where I got a bachelor’s degree in computer engineering. I then got a master’s in electrical engineering and an MBA from Johns Hopkins.

How did you come to Goddard?

In 1985, when I was in my third year of college, I was a summer intern at Goddard. The scientist who interviewed me saw that I had taken electromagnetic theory and, as an interview question, asked me to derive Maxwell’s Equations. So I did. And I was hired.

It was a very strange interview question because the job was to be a programmer. Maxwell’s Equations are the fundamental equations governing classical electrodynamics, optics and electrical circuits. Not many people know what they are, much less know how to derive them.

What did you do after graduating college?

I graduated in 1986 and began working full-time at Goddard in the laboratory for planetary atmospheres. I was programming and working on Pioneer Venus data from the Pioneer Venus Orbiter Neutral Mass Spectrometer.

How did you move from programming to electrical engineering?

After a year, a colleague introduced me to his friend in the Laboratory for High Energy Astrophysics (LHEA) who hired me and became my mentor. He intended to train me to work as an electrical engineer, but he suddenly died about a year after I joined the lab.

I told his successor that I wanted to do electrical design work. He gave me a chance. I worked on Monitoring Xray Experiment, a Russian-American collaborative project. I learned from all the engineers around me.

LHEA has mentored a lot of our electrical engineers and was a great place to start.

What was your next project?

I was able to put my new design skills to work on the Cassini project. I was in my twenties and I was in charge of the Command and Data Handling system and the memory boards for the Cassini Orbiter and Huygens Probe mass spectrometers, GCMS and INMS.

How did you handle the pressure of being only in your twenties and in charge of such important parts of major projects?

In the beginning, I was petrified that I was going to fail. I was scared that someone would find out that I did not know enough. The job evolved and I kept working and figuring things out by reading and learning from others. Eventually, the hardware came together and worked and I began to feel better.

The scariest thing about this project was that the Cassini Huygens Probe had only about 60 minutes to operate. It had to survive the seven years to reach Saturn’s moon Titan, then it would be dropped into the atmosphere of Titan and fall to the surface. It had to do all its work during that one-hour descent, sampling the atmosphere as it fell. No second chances. But it worked, and it told us a lot of what we now know about Titan.

INMS also had to travel seven years to get to Saturn, and its mission was supposed to last for one year. Today after almost 20 years, INMS is still working, still orbiting Saturn and sending back data.

The way I handled it was that I kept testing everything. I kept simulating different conditions, asking myself how each particular part of the hardware and software could possibly fail.

I kept working, learned to work in a team and became more confident over time. Every young engineer eventually learns that success and experience build confidence.

What else have you learned about teamwork?

Every person is important to the team as a whole. Being part of a team means we share the work and we also share the success. No one person can build all the complex hardware we build. To succeed, we must all work together and cooperate.

Who are the most inspiring people you have worked with at Goddard?

I had the privilege of working with an engineer named John Maurer. He is a great engineer and extremely focused on building the best hardware for the application. John taught me a lot. He started working for the Space Physics Research Laboratory (SPRL) at the University of Michigan in the ’50s and has been supporting Goddard since the 1960s.

John is an engineer’s engineer. He understands what it takes to design, build and test space flight instruments. John has great instincts and he knows whether something will work or not, but sometimes even he can’t say why. He also has a unique understanding of what the scientists want, which is reproducible data of the highest quality. He is able to marry the requirement of good science with good engineering.

At SPRL, John worked for a man named Nelson “Spence” Spencer. Spence came from SPRL to Goddard in the1960s. He was also my first boss at Goddard. It was through Spence that John came to work with us.

John mentored another great and insightful University of Michigan engineer, Steve Battel. John and Steve were the systems architects for SAM, the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument suite on the Curiosity rover. Steve was just inducted into the National Academy of Engineering this year. John has since retired. I still call him every so often or so to chat, update him on my work and ask his advice.

My boss in the 1990s was Dr. Hasso Niemann, another amazing man. Hasso graduated from the University of Michigan and also knew the excellent engineers at SPRL. When Hasso won proposals on the Galileo and Cassini missions, he partnered with SPRL to design and build his electronics for his mass spectrometers.

Paul Mahaffy, a scientist at Goddard, took over as the lab chief when Hasso retired. Paul not only gave me opportunities, he trusted me and stood by me through the very, very challenging times when we had to build SAM, NMS and NGIMS simultaneously, again in partnership with the same crew of engineers that built the Cassini mass spectrometers. Everything moved at such a fast pace. Flight hardware typically has problems when it is being built. Paul was extremely conscientious about solving these problems early so they did not come back to haunt us. The fact that all this hardware is successful is a testament to Paul’s leadership and team building skills.

What words of wisdom do you want to pass on to the next generation?

Learn to communicate well. Do not take people for granted. Remember that you are working with people, so do not make assumptions. Talk to teach other. Respect each other. Be honest.

Where are your parents living today?

My parents live with us and often visit my siblings and their families. I am who I am because of my parents, their guidance and their sacrifices. My parents were with us when my children were born and have been instrumental in their upbringing. My parents taught our daughters to speak Hokkien, our mother tongue, when they were quite young. More than that, my parents taught our daughters to be honorable and kind.

What is your “six-word memoir?” A six-word memoir describes something in just six words.

Extroverted. Optimistic. Direct. Meticulous. Complicated. Driven.

Is there something surprising about you that people do not generally know?

I do a lot of volunteer work. I have volunteered at Goddard so often that I am one of the folks on the call for volunteer list. I have volunteered for events at Goddard, at the Smithsonian, and at many science and engineering fairs.

Since 2011, I have supported a fabulous group called “Girls Get Science” targeting K-6th grade girls to encourage more STEM participation. I have spoken at Phillips Exeter Academy’s Assembly, which one of my daughters attended. The students gave me a standing ovation. I have also gone to nursing homes, judged science fairs at schools and tutored mathematics for seven years. I am a certified Yoga teacher and often offer free classes at home and at work.

There is always a call for volunteers. I make it a personal priority to volunteer at least once a month. I spend most of my fall and spring weekends orienteering. Orienteering is a sport in which competitors find their way to various checkpoints in the forest, navigating cross-country with the aid of a map and compass. A typical course has 12 to 15 checkpoints. I have occasionally organized these weekend games and have also prepared the food for 90 people at our annual two-day junior training camps.

I also love to play games, both word games and Euro games. My family will not play Scrabble with me anymore because I always win. I often hold game nights and invite some fellow gamers to my house to play.

Is your family still on the education plan?

Yes, our entire family is still on the education plan. We put all four of my generation through college. My children are finishing college. My niece and nephews are all well-educated and successful. After my husband and I got married, he went to law school. I really believe in the value of a good education.

In the end, I want my children to be happy and content. I want them to be good people and contribute to society and to life.

There is a Hokkien phrase my mom sometimes says that translates as, “bend to the arc of goodness and kindness.” In other words, “be a good person.” That’s what I want my children to become.

What would you like to say to your parents?

Thank you from my heart.

My parents did far more than make education possible. My parents have been there for me my entire life and they are still there for me and my family today. While raising our two girls, my parents made many extended visits to do whatever they could to help. They made it possible for me to have a successful career while my husband and I raised our two girls. They were and remain a very strong influence on our two girls and helped them become the women we hoped they would become.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.