Nature, and more particularly a moth’s eye, inspired the technology that allows a new NASA-developed camera to create images of astronomical objects with far greater sensitivity than was previously possible.

The idea is simple. When examined close up, a moth’s eye contains a very fine array of small tapered cylindrical protuberances. Their job is to reduce reflection, allowing these nocturnal creatures to absorb as a much light as possible so that they can navigate even in the dark.

The same absorber technology concept, when applied to a far-infrared absorber, results in a silicon structure containing thousands of tightly packed, micro-machined spikes or cylindrical protuberances no taller than a grain of sand. It is a critical component of the four 1,280-pixel bolometer detector arrays that a team of scientists and technologists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, created for the High-Resolution Airborne Wideband Camera-plus, or HAWC+.

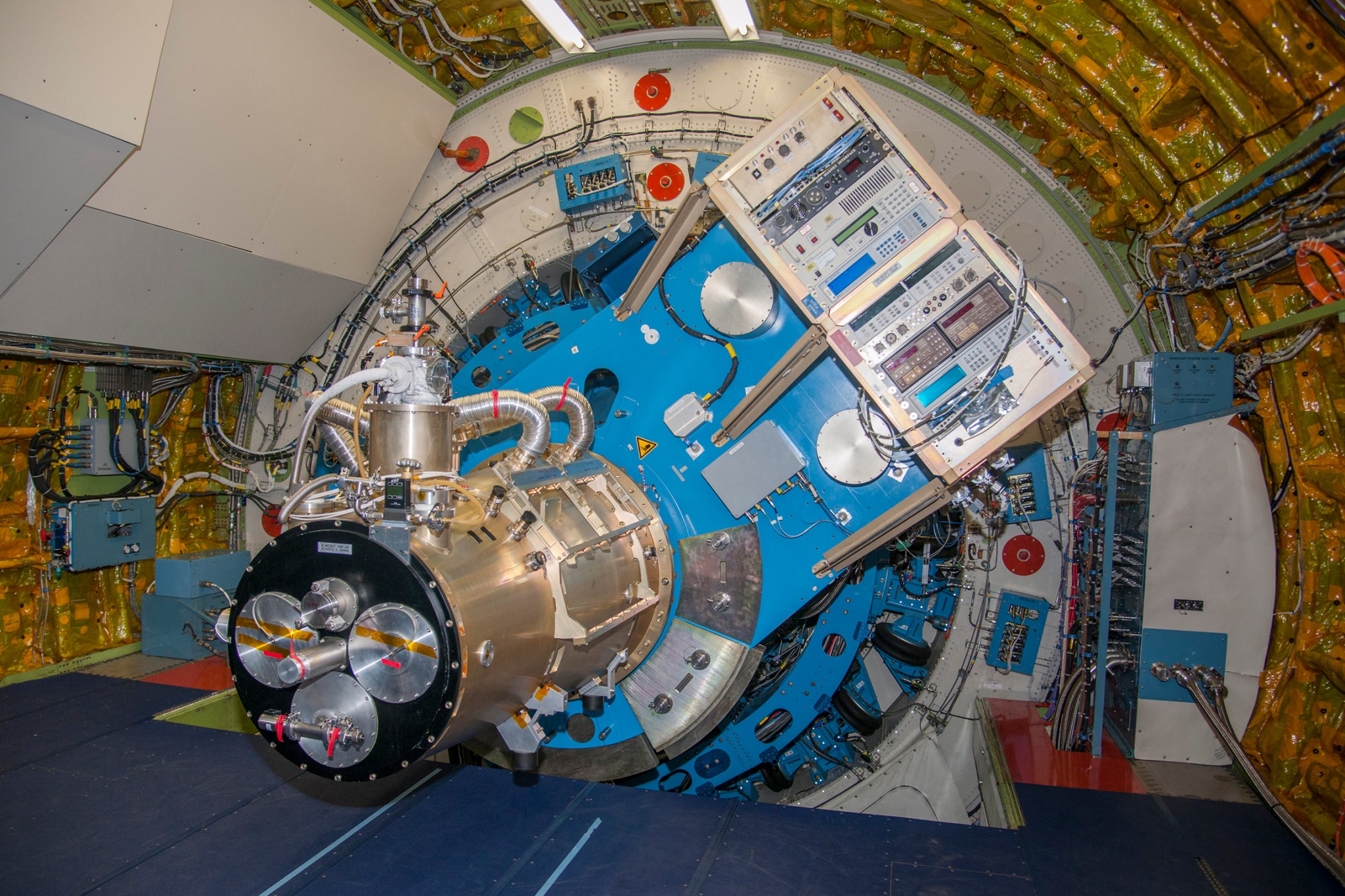

NASA just completed the commissioning of HAWC+ onboard the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, or SOFIA, a joint venture involving NASA and the German Aerospace Center, or DLR. This heavily-modified 747SP aircraft carries with it an eight-foot telescope and six instruments to altitudes high enough not to be obscured by water in Earth’s atmosphere, which blocks most of the infrared radiation from celestial sources.

The upgraded camera not only makes images, but also measures the polarized light from the emission of dust in our galaxy. With this instrument, scientists will be able to study the early stages of star and planet formation, and, with HAWC+’s polarimeter, map the magnetic fields in the environment around the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

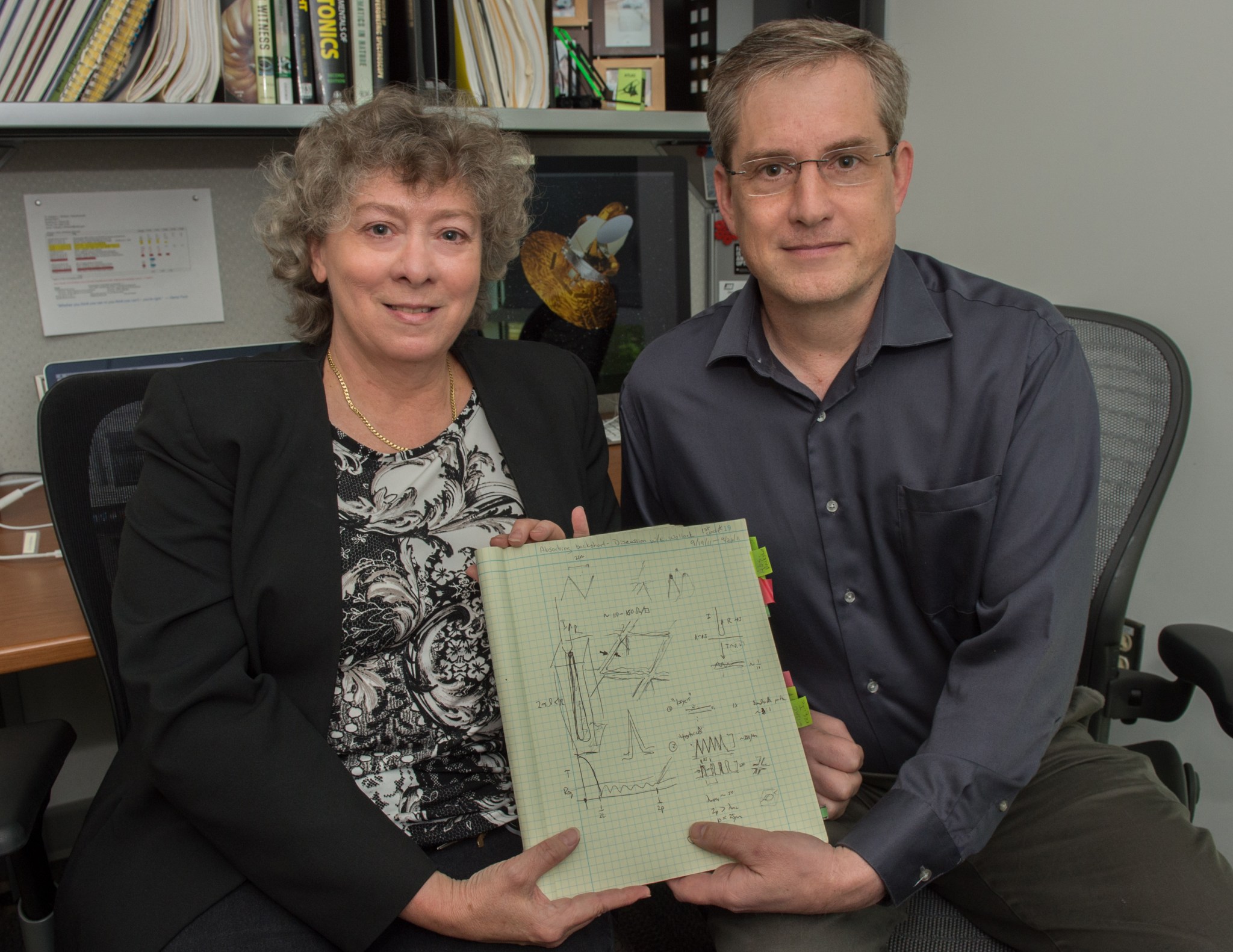

With such a system — never before used in astronomy — even minute variations in the light’s frequency and direction can be measured. “This enables the detector to be used over a wider bandwidth. It makes the detector far more sensitive — especially in the far infrared,” said Goddard scientist Ed Wollack, who worked with Goddard detector expert Christine Jhabvala to devise and build the micro-machined absorbers critical to the Goddard-developed bolometer detectors.

Bolometers are commonly used to measure infrared or heat radiation, and are, in essence, very sensitive thermometers. When radiation is focused and strikes an absorptive element, typically a material with a resistive coating, the element is heated. A superconducting sensor then measures the resulting change in temperature, revealing the intensity of the incident infrared light.

This particular bolometer is a variation of a detector technology called the backshort under-grid sensor, or BUGS, used now on a number of other infrared-sensitive instruments. In this particular application, the reflective optical structures — the so-called backshorts — are replaced with the micro-machined absorbers that stop and absorb the light.

The team had experimented with carbon nanotubes as a potential absorber. However, the cylindrically shaped tubes now used for a variety of spaceflight applications proved ineffective at absorbing far-infrared wavelengths. In the end, Wollack looked to the moth as a possible solution.

“You can be inspired by something in nature, but you need to use the tools at hand to create it,” Wollack said. “It really was the coming together of people, machines, and materials. Now we have a new capability that we didn’t have before. This is what innovation is all about.”