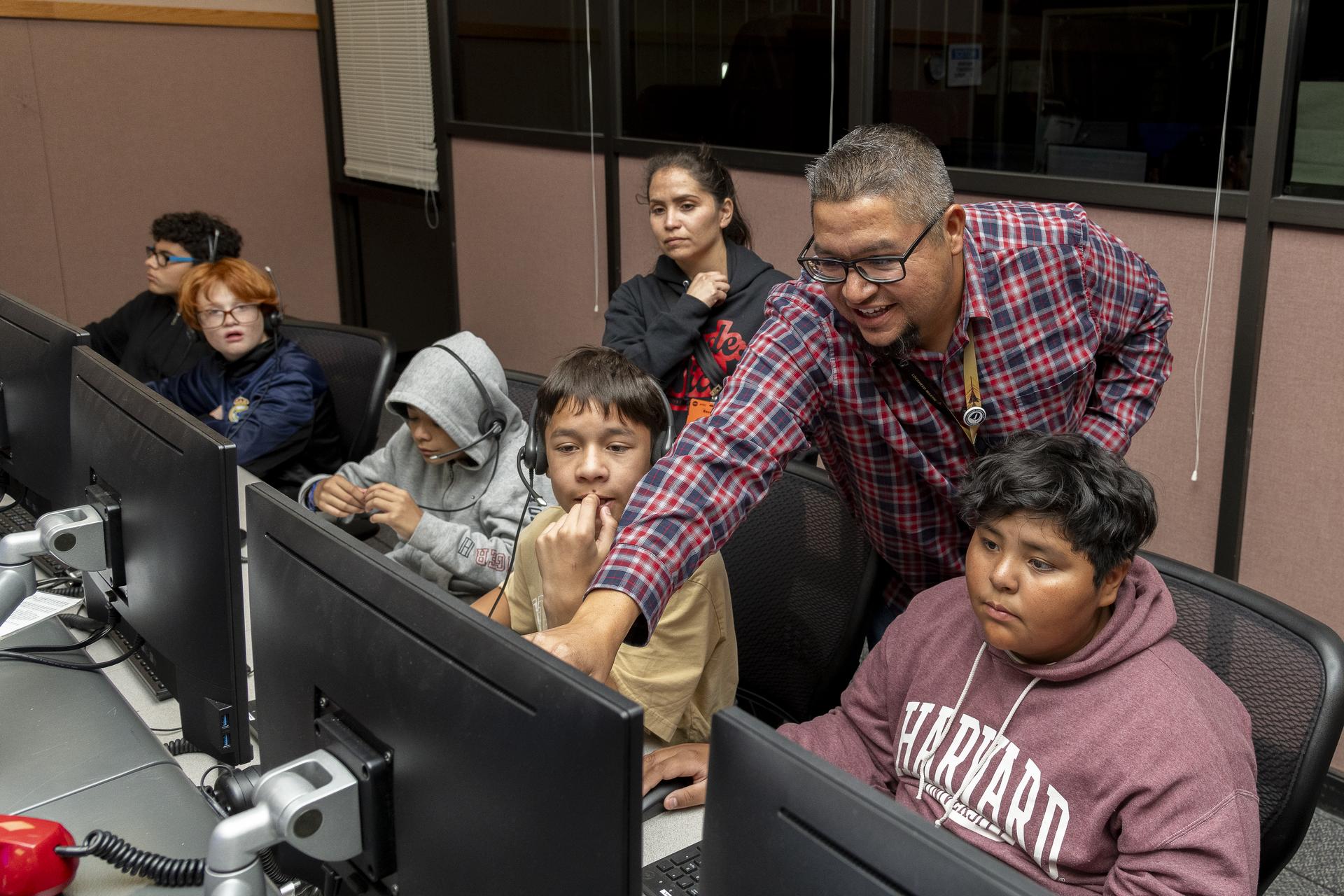

Science and technology advancements start with big ideas and creativity. Researchers at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland have imagined a new, early-stage concept for a lander to Saturn’s moon Titan. The team is exploring technologies capable of collecting surface samples and returning them to Earth for laboratory analysis.

The team’s futuristic idea was selected for a $125,000 NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program grant to begin studying the concept’s feasibility.

“NIAC is one way the agency fosters ‘wild’ ideas that require a decade or more of development but could eventually lead to revolutionary innovations that contribute to new and exciting missions,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate. “The missions of today were ‘wild’ ideas years ago.”

The scientists and engineers working on the Titan sample return concept are part of Glenn’s Compass Lab. Previously, the group envisioned a submarine that would explore the shores and depths of Titan’s methane seas.

Why Titan? Titan can help us understand the origins of the solar system.

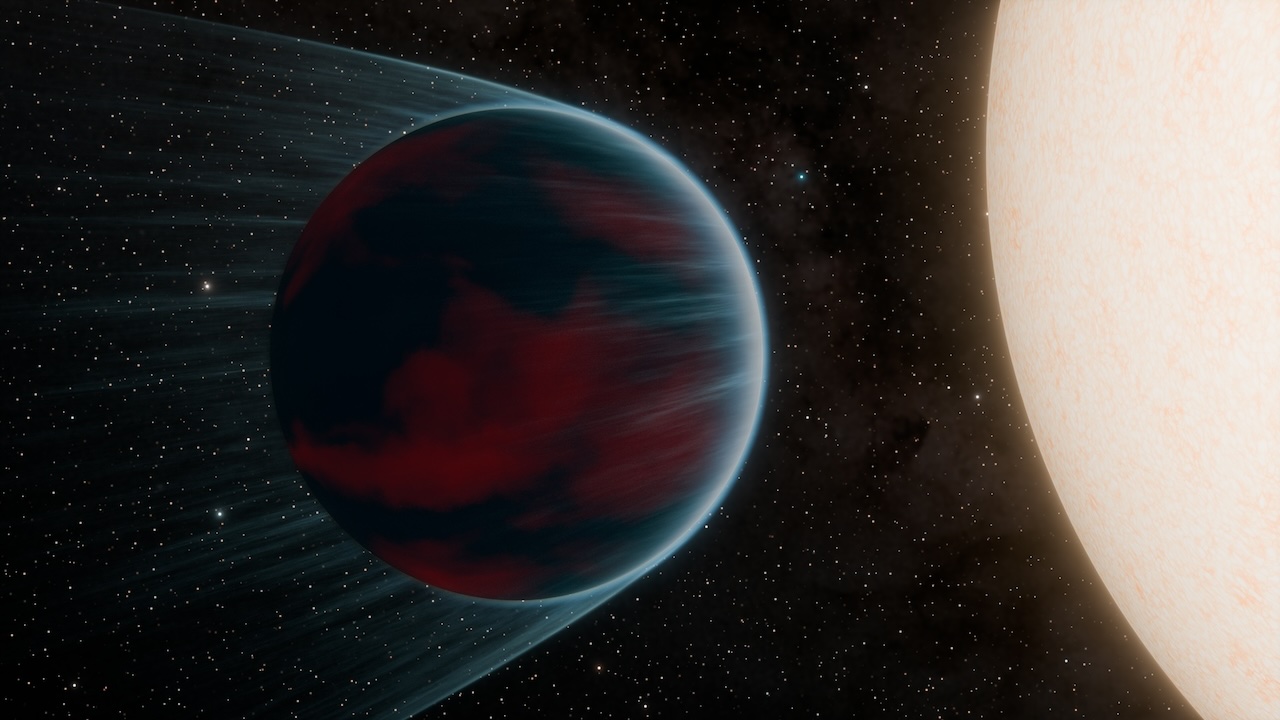

“Titan is an amazing world,” said Geoffrey Landis, the science lead investigator for Compass. “It is covered in organic compounds protected with a thick nitrogen atmosphere and has liquid natural gas seas the size and depth of Earth’s Great Lakes on its surface. And beneath its crust, Titan is an ocean world, with a second ocean of liquid water hidden deep below the surface.”

The organic compounds on the surface and in the atmosphere, called tholins, are only found in the outer solar system and are likely some of the building blocks of the solar system that could help us understand the origin of life on our own planet. Landis added that while some limited analysis of these compounds may be possible using lightweight instruments on a probe, a more detailed understanding would come from bringing samples back to be analyzed with sophisticated laboratories on Earth.

Traveling to Titan takes time; it’s about a seven-year journey from Earth. NASA’s first mission to study Titan up close is an 8-bladed rotorcraft called Dragonfly. Slated for launch in 2026, it will explore the atmosphere and surface for two years.

The exciting prospect of bringing Titan samples back to Earth would give scientists even more insight into this mysterious moon.

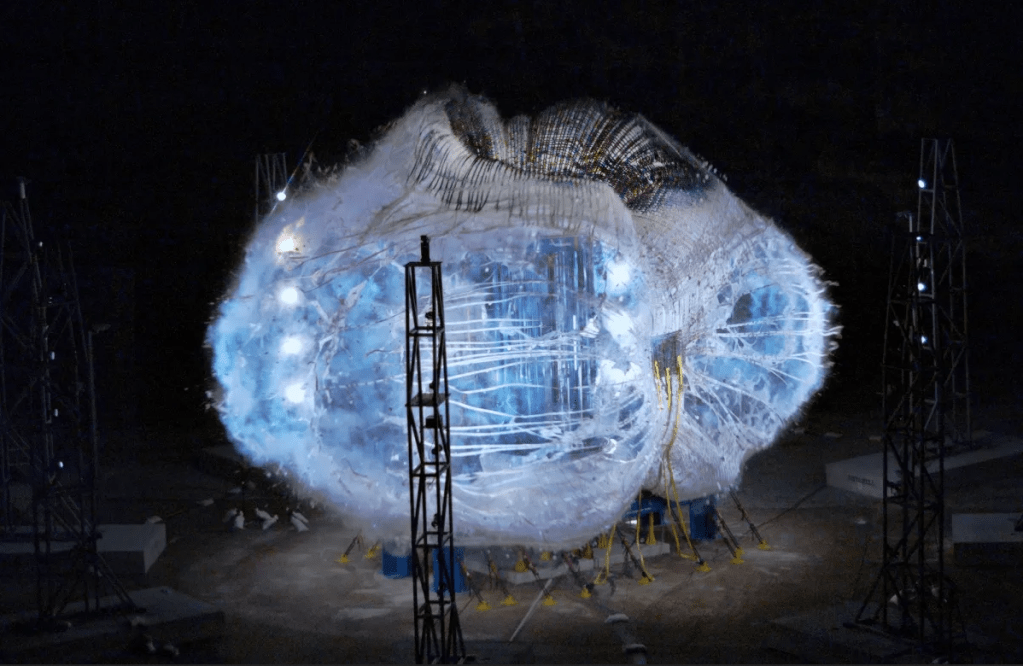

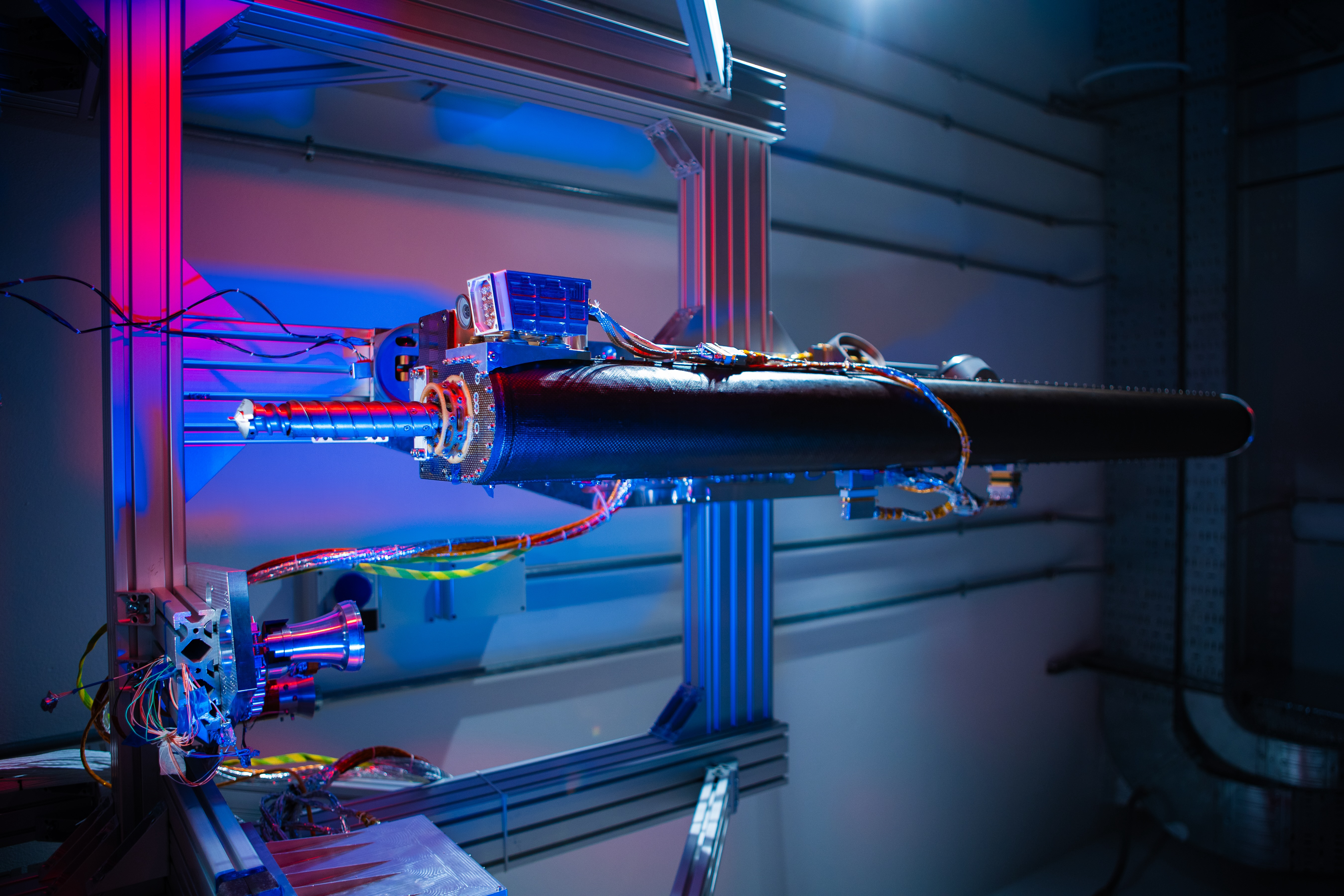

“We expect landing on Titan to be relatively easy,” said Steven Oleson, lead of the Compass Lab and principal investigator for the NIAC study. “Titan has a thick atmosphere of nitrogen — 1.5 times the atmospheric pressure of Earth — which can slow the lander’s velocity with an aeroshell and a parachute for a soft landing, just like astronauts returning to Earth.”

Unlike Mars landers, a mission to Titan does not need a final rocket-powered descent stage.

Titan is also rich in materials that could potentially fuel a mission’s return to Earth. The Compass team will investigate technologies that could find the resources to produce propellant to power the trip home.

“Our aim is to design a cost-effective modern mission concept that could find and use resources at the destination,” explains Landis.

“Producing rocket fuel on Titan wouldn’t require chemical processing—you just need a pipe and a pump,” explained Oleson. “The methane is already in a liquid state, so it’s ready to go.

The trickier part is creating the liquid oxygen. Titan’s rocks are made of water ice that could be melted using the heat from a nuclear source and then electrolyzed to produce oxygen.

Like all NIAC studies, funded by the agency’s Space Technology Mission Directorate, this project is in the early stages of development and is not an official NASA mission. However, by supporting visionary research ideas through multiple phases of study, the agency develops new cross-cutting technologies needed for current and future missions.

Nancy Smith Kilkenny

NASA Glenn Research Center