In the 20 months following the first piloted Gemini mission, NASA astronauts demonstrated the ability to change orbits, perform rendezvous and docking, along with spending up to two weeks in space. Spacewalking, on the other hand, remained an enigma. With only one more Gemini flight on the schedule, solving the problems of working outside a spacecraft would be the primary goal for Gemini XII.

As was the case on the previous four missions, the Gemini XII flight plan called for rendezvous and docking with a target vehicle. But, according to Dr. George Mueller, NASA’s associate administrator for Manned Spaceflight, mastering what NASA called an extravehicular activity (EVA) or spacewalk would be crucial in proving the agency was ready to move ahead with Apollo and achieving the goal of landing a man on the moon before the end of the decade.

“I feel that we must devote the last EVA period in the Gemini Program to a basic investigation of EVA fundamentals,” he said.

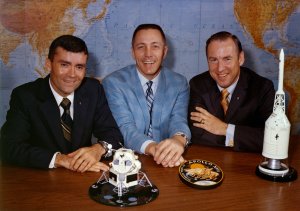

To take on the challenges of this crucial flight, NASA assigned a veteran of the longest spaceflight to date and the astronaut who helped “write the book” on orbital rendezvous.

The command pilot was Jim Lovell who served on the 14-day Gemini VII mission in December 1965. A Naval aviator, he went on to be a member of the Apollo 8 crew, the first mission to orbit astronauts around the moon in 1968. As commander of Apollo 13 in 1970, Lovell became the first person to travel in space four times.

Flying with Lovell was U.S. Air Force pilot, Buzz Aldrin, the first astronaut to have earned a doctorate. In 1963, he was awarded a doctorate in astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His graduate thesis was “Line-of-sight guidance techniques for manned orbital rendezvous.” Aldrin went on to serve as lunar module pilot on Apollo 11 in 1969, during which he and Neil Armstrong become the first humans to walk on the moon.

To make lunar EVAs possible, spacewalking during Gemini flights was a crucial learning experience in Gemini. Ed White’s spacewalk on Gemini IV made it look easy. But the experiences of Gene Cernan, Mike Collins and Dick Gordon on three later missions demonstrated a new approach was needed for both training and performing spacewalks.

Through Gemini XI, EVA training focused on use of the KC-135 aircraft flying parabolas. During the dives, astronauts experienced up to 30 seconds of weightlessness. But this was followed by the aircraft climbing and the astronauts having a period of rest. Consequently, spacewalkers in training were not facing the types of continued strenuous work and fatigue experienced by Cernan, Collins and Gordon.

Dr. Robert Gilruth, director of the Manned Spacecraft Center (now Johnson Space Center) in Houston, ordered a new approach.

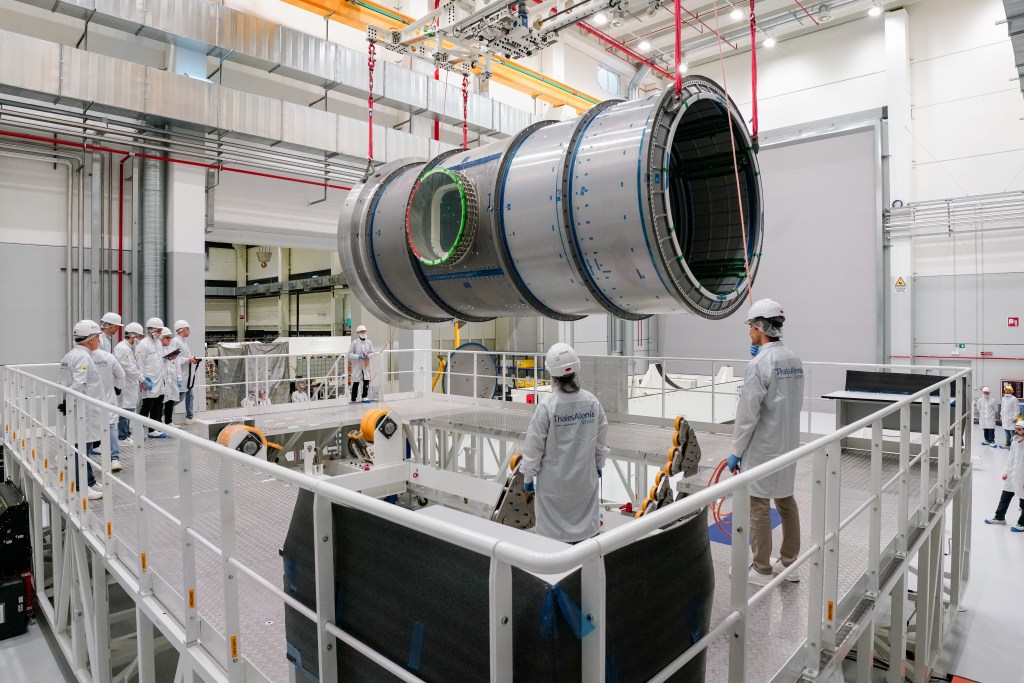

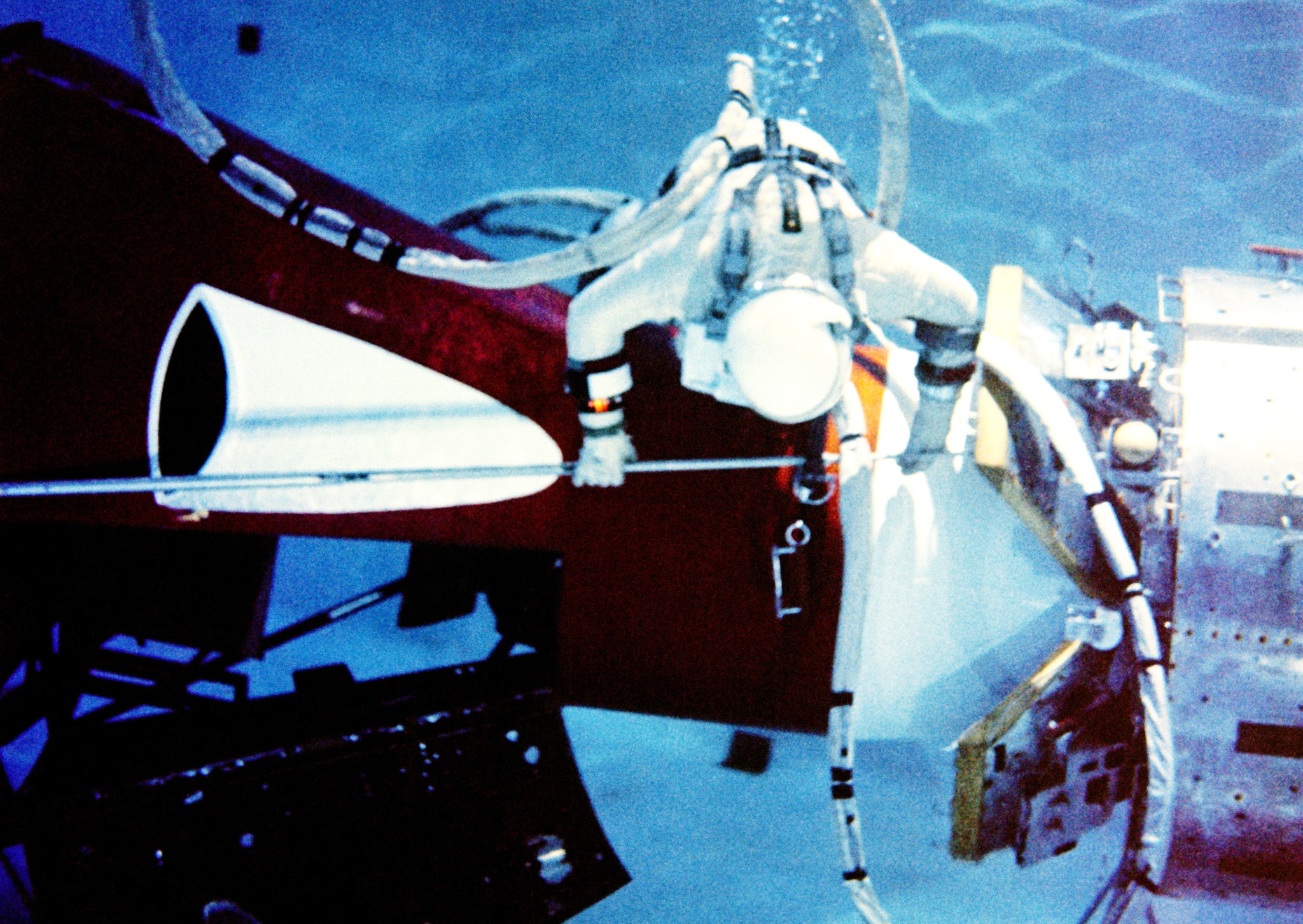

“I have given a great deal of thought recently to the subject of how best to simulate and train for extravehicular activities,” Gilruth said in memo to Deke Slayton, director of Flight Crew Operations. “Both zero ‘g’ trajectories in the KC-135 and underwater simulations should have a definite place in our training programs.”

The alternate approach uses a large pool of water for “neutral buoyancy.” In this method special weights are added to the astronaut’s spacesuit creating buoyancy to offset gravity so the astronaut neither rises nor sinks.

Aldrin spent several sessions of more than two hours each working with a Gemini mockup in the pool at the Environmental Research Associates facility near Baltimore, Maryland.

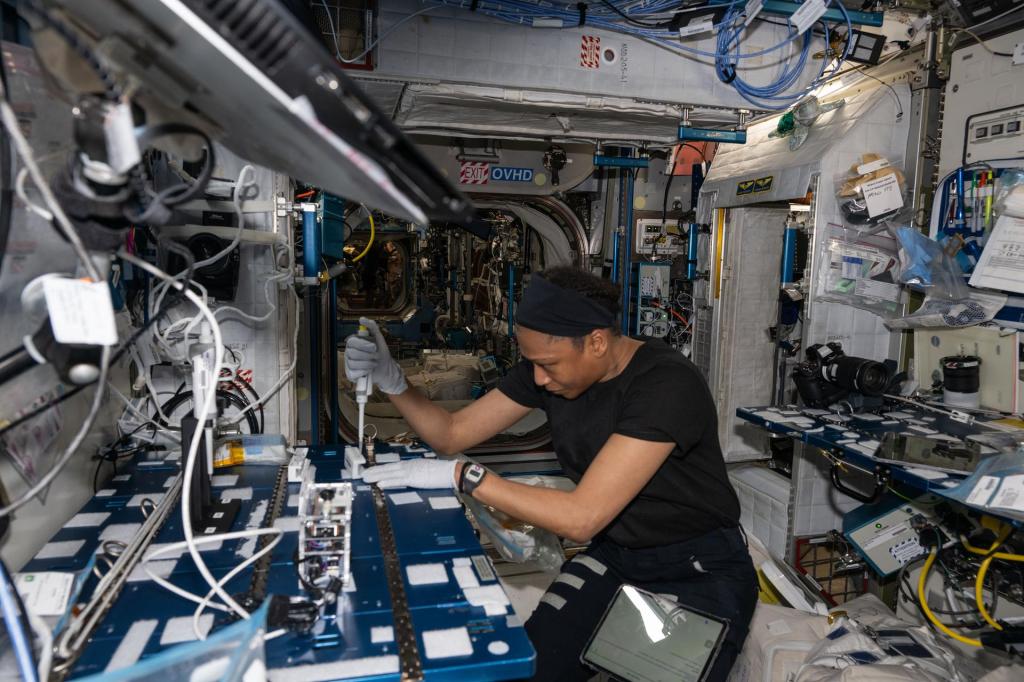

This approach became so successful, underwater training has become the primary spacewalk training method used by the United State, Russia and China. Today, NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston is large enough to include mockups of major sections of the International Space Station. As such, it is the largest indoor body of water in the world, with 6.2 million gallons of water.

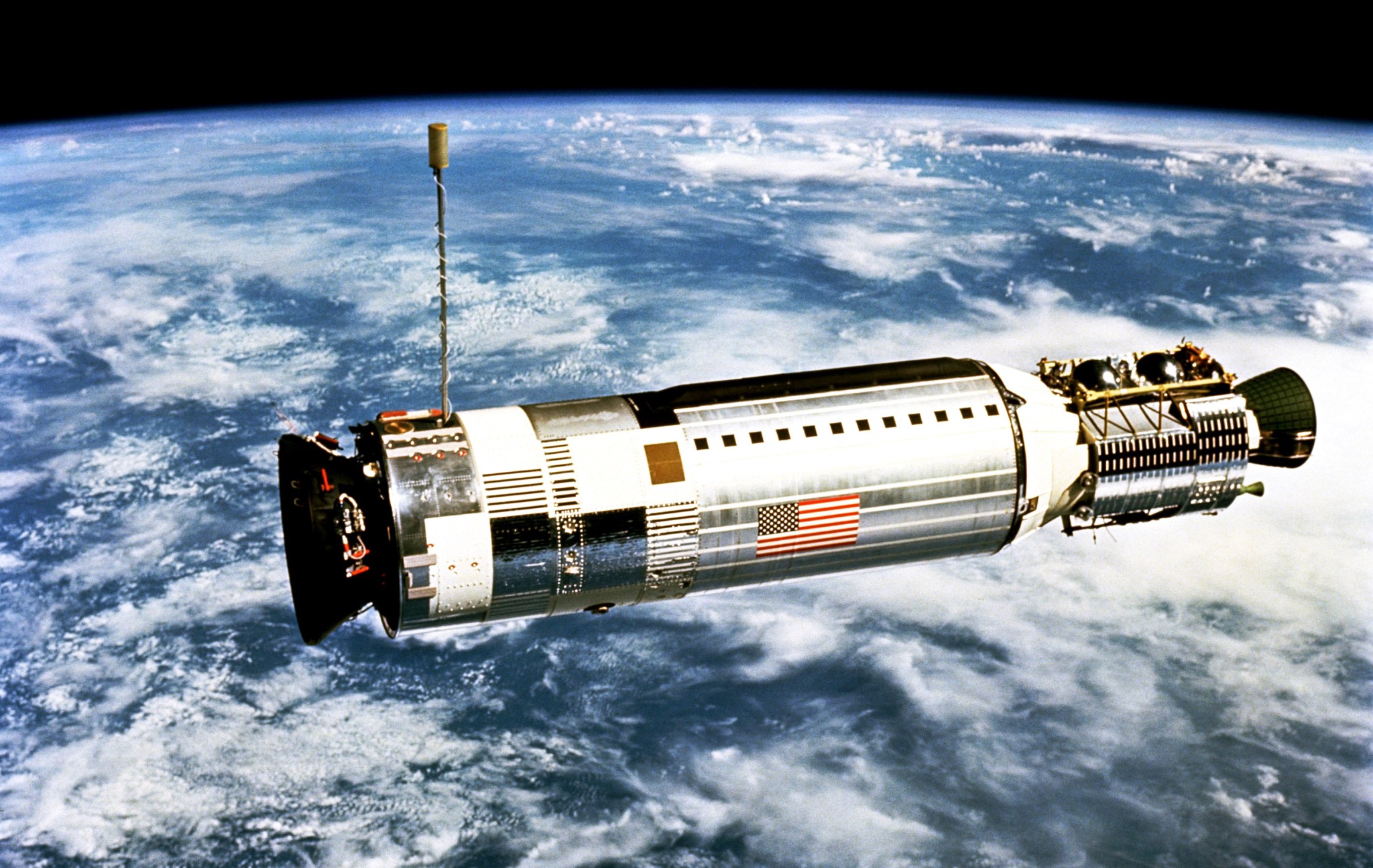

With the additional training behind them, Lovell and Aldrin lifted off aboard their Gemini XII spacecraft atop a Titan II rocket on Nov. 11, 1966. They followed one hour, 39 minutes after their Agena was placed in orbit by an Atlas launch vehicle.

The first order of business was rendezvous with the Agena. Things were going well when Lovell confirmed they spotted their target 98 miles away. But minutes later there was trouble.

“We seem to have lost our radar lock-on at about 74 miles,” Aldrin said. “We don’t seem to be able to get anything through the computer.”

Aldrin pulled out a sextant and his slide rule and put his MIT doctoral research to work. With the sextant, Aldrin measured the angle between the horizon and the Agena. Aldrin confirmed the information with his rendezvous chart, then calculated corrections with the spacecraft’s computer.

“How are you doing up there?” asked fellow astronaut Pete Conrad during the third orbit. He was serving as capsule communicator, known as capcom, in Mission Control.

“We’re taking pictures of the beautiful Agena here,” Lovell said as Gemini XII closed in on its target.

“We’re giving you a GO for docking,” Conrad said.

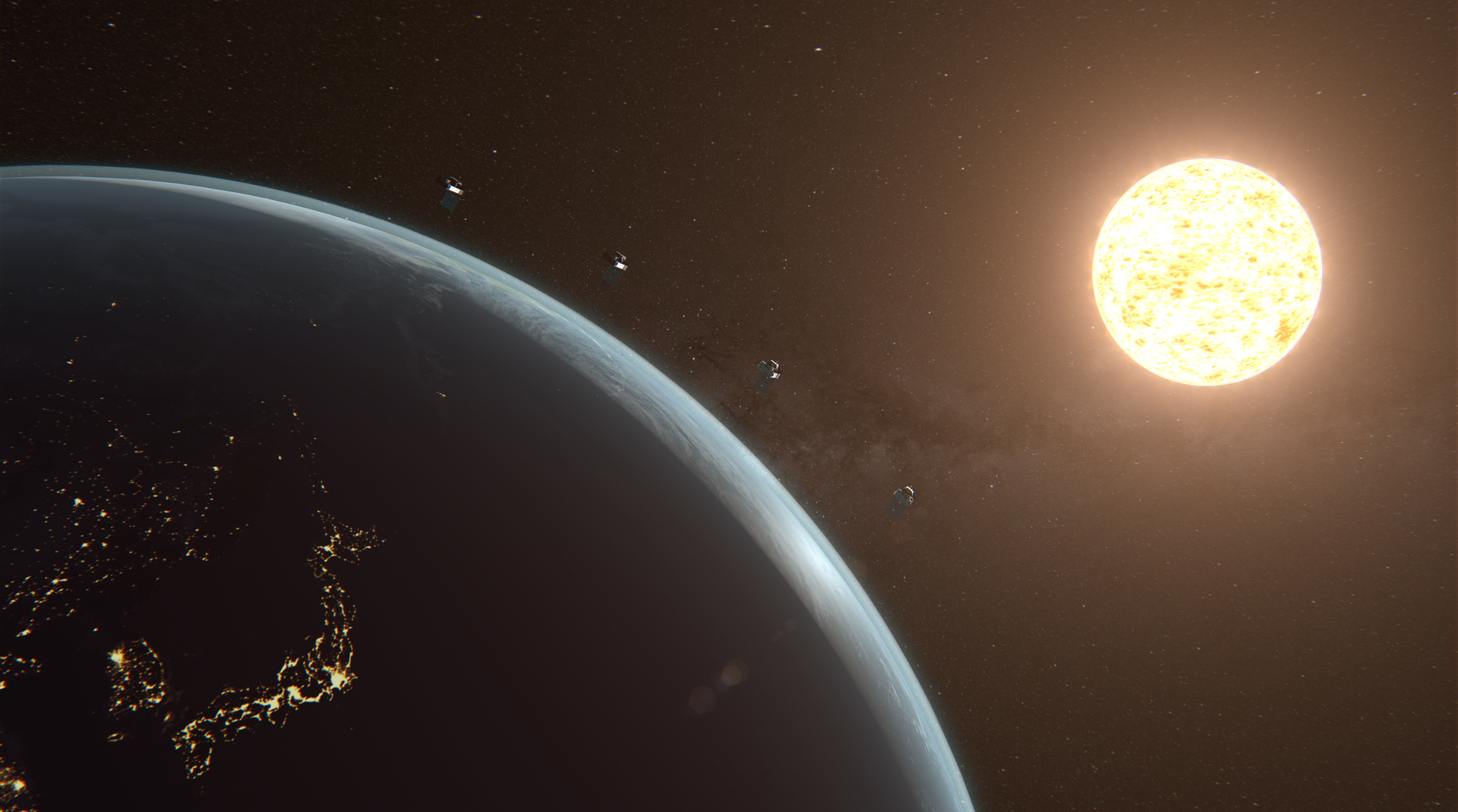

“We are docked,” Lovell reported four minutes later as the combined spacecraft orbited south of Japan in range of the tracking ship Coastal Sentry Quebec.

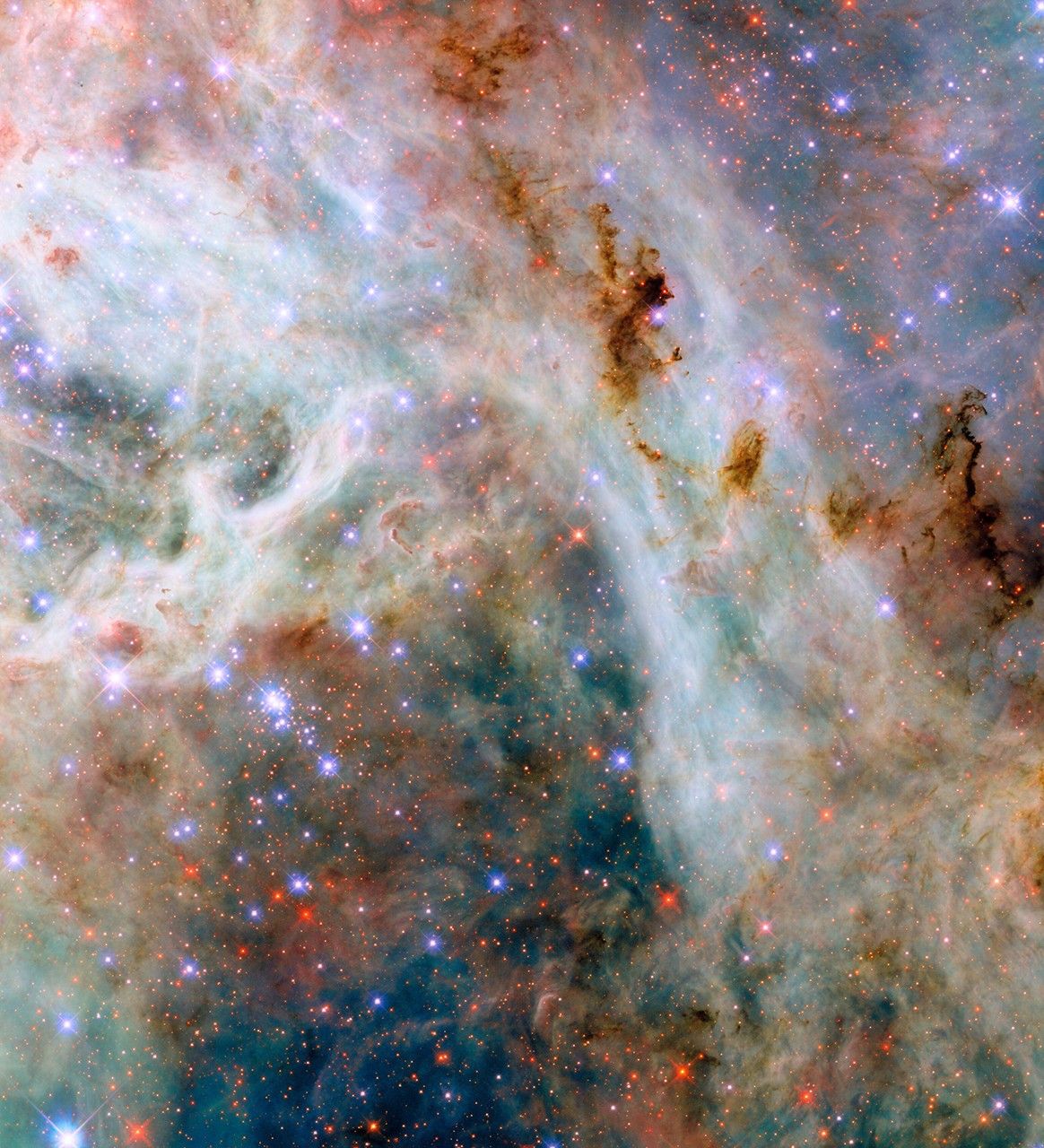

During flight day two, Aldrin began practicing some of the new processes for spacewalks. This would be a two-hour, 18 minute EVA limited to standing in the hatch to familiarize himself with the environment, as well as conducting Earth and ultraviolet astronomical photography.

“The hatch is coming open,” he said. “Man, look at that.”

Aldrin expressed amazement seeing so much of Earth and the universe once outside the confines of the spacecraft.

One of his first jobs was to install a handrail between his hatch and the docking collar of the Agena. This would aid his movements during a full spacewalk the next day. As Aldrin took pictures of landmarks on Earth, he offered the usual photographer’s “suggestion.”

“Okay, tell everybody down there to smile,” he said to capcom Conrad.

Having set up a camera on the edge of his hatch, Aldrin pointed the camera in his direction.

“Now let me raise my visor and I’ll smile,” he said taking what Aldrin now describes as “the first space selfie.”

With the space stand-up EVA completed, the next day came the crucial test of a new approach to spacewalking.

“I’m free now and the only thing that’s holding me is the one hand on the handrail,” Aldrin said as he used the aid he installed the day before.

In addition to revised preflight training techniques, more handrails and handholds were added along with a waist tether giving the spacewalker the ability to turn wrenches and retrieve experiment packages without undue effort.

Aldrin’s approach was to go about his work slowly and deliberately. He would work for a while then rest, even if a reminder was needed.

“Now do you know what you’re going to do?” Lovell asked.

“Go ahead, clue me in,” Aldrin said.

“You’ll get a rest for two minutes,” Lovell said.

Aldrin then attached a tether from the Agena for the gravity-gradient experiment. With the handholds, he did not experience the problems Gordon encountered on the previous flight.

Next, Aldrin moved to the spacecraft’s aft adapter where he placed his feet in overshoe restraints and attached waist tethers. With these supports in place, he was able to fasten rings and hooks, connect and disconnect electrical and fluid connections, tighten bolts and cut cables.

“I’ve got the cutters,” Aldrin said. “They’re cutting the strap seam quite nicely.”

Aldrin again went forward to a box attached to the Agena. Lovell photographed him as he pulled electrical connectors apart and put them together again, then tried out a torque wrench designed for the Apollo program.

With all his work successfully competed and with no fatigue, Aldrin returned to his Gemini seat after two hours, nine minutes outside.

The riddle of spacewalking was solved.

The next task for Gemini XII was to undock from the Agena and maneuver their craft to keep taut the tether attached by Aldrin during his spacewalk. By firing their thrusters to slowly rotate the combined spacecraft, they, like Gemini XI, were able to use centrifugal force to generate a small amount of gravity during the four hour, 20 minute exercise.

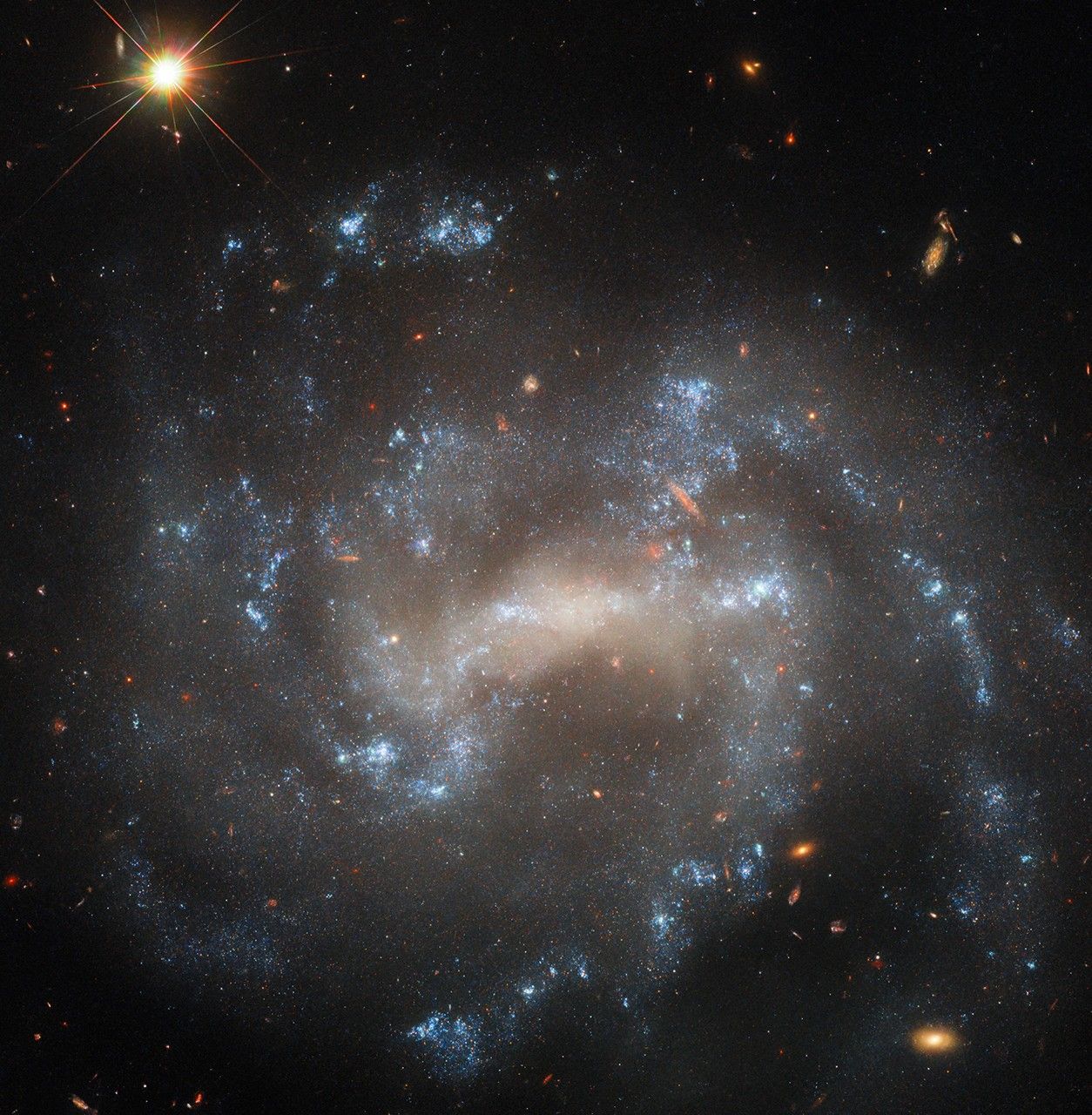

Aldrin’s third time outside Gemini XII and his second stand-up on the seat spacewalk, was on the fourth flight day. He took numerous ultraviolet photographs of stars and constellations during one hour, 11 minutes outside.

After the mission, NASA’s “Summary of Gemini Extravehicular Activity” noted that Gemini XII’s spacewalks demonstrated all the tasks attempted were feasible when body restraints were used to maintain position. But, “the most significant result was that underwater simulation duplicated the actual extravehicular actions and reactions with a high degree of fidelity.”

Another repeat of a test on Gemini XI was a computer controlled re-entry on Nov. 15, 1966.

“Gemini XII, Houston,” capcom Conrad said. “Our data shows you right on the money.”

In fact, Lovell and Aldrin splashed down just three miles from their target, near the recovery aircraft carrier USS Wasp sailing 600 miles east of Cape Kennedy.

The next day, Lovell and Aldrin were flown from the USS Wasp to the Cape’s skid strip where they were welcomed by Kennedy’s center director, Dr. Kurt Debus.

“We feel everyone here did an outstanding job in getting us into space,” Lovell said to those in attendance. “It takes a lot of people to fulfill a program. It’s the untiring efforts of thousands who got us up to there and back.”

Gemini Program Manager Walt Williams looked ahead to Apollo.

“It is now time to go on,” he said. “We will be able to go on with confidence because there was this program and it was called Gemini.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson also had high praise for those who made the Gemini Program possible.

“Today’s flight was the culmination of a great team effort, stretching back to 1961,” he said. ”It directly involved more than 25,000 people in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Department of Defense, other government agencies, universities, other research centers and in American industry.”

The President then looked forward to Apollo.

“The months ahead will not be easy, as we reach toward the moon,” he said, ”but with Gemini as the forerunner, I am confident that we will overcome the difficulties and achieve another success.”

By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the final article in a series of features marking the 50th anniversary of Project Gemini. The program was designed as a steppingstone toward landing on the moon. The investment also provided technology now used in NASA’s work aboard the International Space Station and planning for the Journey to Mars. For more, see “On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini.” If you missed any of the features in this series, click on any of the links below.

- Gemini III: Gemini Pioneered the Technology Driving Today’s Exploration

- Gemini IV: Learning to Walk in Space

- Gemini V: Paving the Way for Long Duration Spaceflight

- Gemini VII & Gemini VI: Dual Gemini Flights Achieved Crucial Spaceflight Milestones

- Gemini VIII: Gemini’s First Docking Turns to Wild Ride in Orbit

- Gemini IX Crew Found ‘Angry Alligator’ in Earth Orbit

- Gemini X Set Records for Rendezvous, Altitude Above Earth

- Gemini XI: Demanding Mission Flies on Top of the World

- Gemini XII: Crew Masters the Challenges of Spacewalks