A very small instrument has a big job ahead of it: measuring all Earth-directed energy coming from the Sun and helping scientists understand how that energy influences our planet’s severe weather, climate change and other global forces.

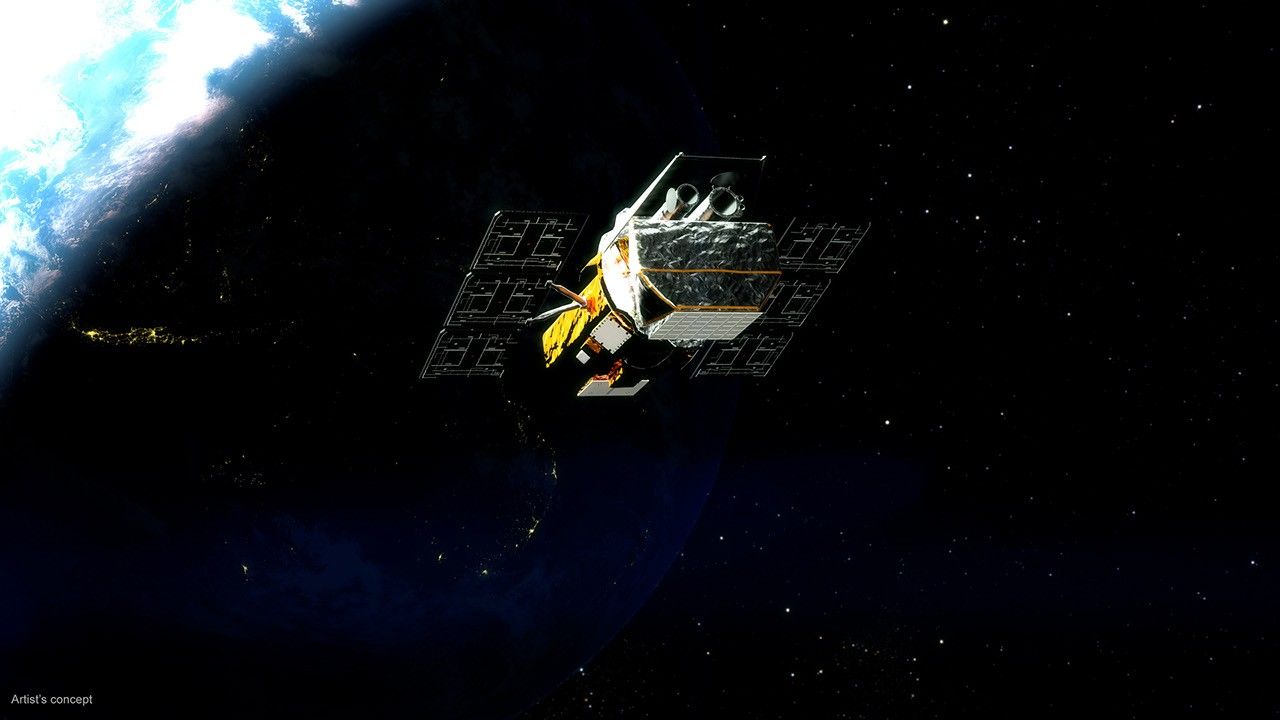

About the size of a shoebox or gaming console, the Compact Total Irradiance Monitor (CTIM) is the smallest satellite ever dispatched to observe the sum of all solar energy Earth receives from the Sun — also known as “total solar irradiance.”

Credits: NASA/Willaman Creative

Total solar irradiance is a major component of the Earth radiation budget, which tracks the balance between incoming and outgoing solar energy. Increased amounts of greenhouse gases emitted from human activities, such as burning fossil fuels, trap increased amounts of solar energy within Earth’s atmosphere.

That increased energy raises global temperatures and changes Earth’s climate, which in turn drives things like rising sea levels and severe weather.

“By far the dominant energy input to Earth’s climate comes from the Sun,” said Dave Harber, a senior researcher at the University of Colorado, Boulder, Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) and principal investigator for CTIM. “It’s a key input for predictive models forecasting how Earth’s climate might change over time.”

NASA missions like the Earth Radiation Budget Experiment and NASA instruments like CERES have allowed climate scientists to maintain an unbroken record of total solar irradiance stretching back 40 years. This enabled researchers to rule out increased solar energy as a culprit for climate change and recognize the role greenhouse gases play in global warming.

Ensuring that record remains unbroken is of paramount importance to Earth scientists. With an unbroken total solar irradiance record, researchers can detect small fluctuations in the amount of solar radiation Earth receives during the solar cycle, as well as emphasize the impact greenhouse gas emissions have on Earth’s climate.

For example, last year, researchers from NASA and NOAA relied on the unbroken total solar irradiance record to determine that, between 2005 and 2019, the amount of solar radiation that remains in Earth’s atmosphere nearly doubled.

“In order to make sure we can continue to collect these measurements, we need to make instruments as efficient and cost-effective as possible,” Harber said.

CTIM is a prototype: its flight demonstration will help scientists determine if small satellites could be as effective at measuring total solar irradiance as larger instruments, such as the Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM) instrument used aboard the completed SORCE mission and the ongoing TSIS-1 mission on the International Space Station. If successful, the prototype will advance the approaches used for future instruments.

CTIM’s radiation detector takes advantage of a new carbon nanotube material that absorbs 99.995% of incoming light. This makes it uniquely well suited for measuring total solar irradiance.

Reducing a satellite’s size reduces the cost and complexity of deploying that satellite into low-Earth orbit. That allows scientists to prepare spare instruments that can preserve the TSI data record should an existing instrument malfunction.

CTIM’s novel radiation detector – also known as a bolometer – takes advantage of a new material developed alongside researchers at the National Institute for Standards and Technology.

“It looks a bit like a very, very dark shag carpet. It was the blackest substance humans had ever manufactured when it was first created, and it continues to be an exceptionally useful material for observing TSI,” Harber said.

Made of minuscule carbon nanotubes arranged vertically on a silicon wafer, the material absorbs nearly all light along the electromagnetic spectrum.

Together, CTIM’s two bolometers take up less space than the face of a quarter. This allowed Harber and his team to develop a tiny instrument fit for gathering total irradiance data from a small CubeSat platform.

A sister instrument, the Compact Spectral Irradiance Monitor (CSIM), used the same bolometers in 2019 to successfully explore variability within bands of light present in sunlight. Future NASA missions may merge CTIM and CSIM into a single compact tool for both measuring and dissecting solar radiation.

“Now we’re asking ourselves, ‘How do we take what we’ve developed with CSIM and CTIM and integrate them together,’” Harber said.

Harber expects CTIM to begin collecting data about a month after launch, currently scheduled for June 30, 2022, aboard STP-28A, a Space Force mission executed by Virgin Orbit. Once Harber and his LASP colleagues unfold CTIM’s solar panels and check each of its subsystems, they will activate CTIM. It’s a delicate process, one that requires diligence and extreme care.

“We want to take our time and make sure that we’re doing these steps rigorously, and that each component of this instrument is working correctly before we move on to the next step,” Harber said. “Just demonstrating that we can gather these measurements with a CubeSat would be a big deal. That would be very gratifying.”

Funded through the InVEST program in NASA’s Earth Science Technology Office, CTIM launches from the Mojave Air and Space Port in California aboard Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne rocket as part of the United States Space Force STP-S28A mission.

Another NASA graduate from the InVEST technology program, NACHOS-2, will also be aboard. A NACHOS twin, NACHOS-2 will help the Department of Energy monitor trace gases in Earth’s atmosphere.

By Gage Taylor

NASA’s Earth Science Technology Office