By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

On a brisk day just over a century ago, what started as a venture between two brothers changed the world forever. On Dec. 17, 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright opened the world of air travel with their first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. In 10 short years, commercial aviation became a reality. Fast forward another 50 years and humans not only were flying in the air, but also in space. After another half-century of spaceflight, NASA and its industry partners now are on the verge of inaugurating the Commercial Crew Program, ferrying astronauts to the International Space Station, once again launching humans from American soil.

Individual inventors such as the Wight Brothers were the original investors in the early development of aviation. They were successful because of their willingness to challenge a belief held by many that human flight was impossible.

“If we worked on the assumption that what is accepted as true really is true, then there would be little hope for advance,” said Orville Wright.

Various government agencies, such as the military, soon showed interest. Once it became cost-effective to carry paying customers, commercial aviation also took off – just as commercial space is today.

First Commercial Flight

The first paying fixed-wing passenger checked his bag on Jan. 1, 1914. Pilot Tony Jannus flew his customer, Abram Pheil, from St. Petersburg to Tampa, Florida. The trip across the 21 miles of Tampa Bay took 23 minutes.

Jannus auctioned off the privilege of traveling on this inaugural flight with prospective passengers bidding large amounts of money for the one seat. Pheil, a former mayor of St. Petersburg, was the winner paying $400 ($5,000 in today’s currency) for the privilege.

On that New Year’s Day in 1914, one person flew one commercial flight. A century later, the International Air Transportation Association estimates 8 million passengers fly world-wide on almost 100,000 flights each day. That equates to almost 3 billion air travelers every year.

One of the first commercial uses of aviation was delivering mail. The first experimental American airmail delivery was made on Sept. 23, 1911, under the authority of the U.S. Post Office Department. The service was intermittent until domestic U.S. Air Mail was formally established by the Post Office Department on May 15, 1918. At that time the first special Air Mail stamps were issued.

The U.S. government began to take a serious role in the development of the aviation age with the formation of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or the NACA, on March 3, 1915. The NACA was established to “undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research.”

Part of the U.S. government’s early interest in aviation centered on possible military applications. In fact, aviation proved to be a viable industry with the onset of World War I.

In 1914, the U.S. Census Bureau listed only 16 aircraft companies. Their collective output was 49 aircraft.

By the end of the First World War, 175,000 people were employed at 300 airplane manufacturing plants in the United States. By the time of the armistice on November 11, 1918, the new industry produced 13,844 aircraft.

Airports Begin Dotting America

Along with a flourish of commercial airlines, airfields were springing up across America. In 1923, Atlanta alderman William Hartsfield was assigned to find a place for a new airport. The goal was to convince the U.S. Post Office Department to give the Georgia capital one of the contracts for a lucrative air mail route.

Candler Field in the Atlanta suburb of Hapeville, Georgia, was originally an auto racetrack similar to the one at Indianapolis, Indiana. Through Hartsfield’s efforts, barnstormers and former World War I aviators began flying in and out of Atlanta in the early 1920s. On Sept. 15, 1926, Atlanta aviation history was made when the first air mail flight took off from the city.

Hartsfield went on to serve as Atlanta’s mayor and the airport is now named for him and Mayor Maynard Jackson. During the late 1970s, Jackson helped lead the effort to build a modern airport terminal, which opened in 1980. According to the Airports Council International’s “World Airport Traffic Report,” the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport is the busiest in the world with more than 96 million people passing through the hub each year.

First Modern Passenger Airliners

The Boeing 247 is considered the first modern passenger airliner. Introduced in 1933, the aircraft was similar to a low-wing, twin-engine military bomber with retractable landing gear. Put into service by United Air Lines, it could accommodate 10 passengers and travel at 155 mph.

At about the same time, the Douglas Aircraft Co. DC-3 became a popular airliner due to its cruising speed of 207 mph and a range of 1,500 miles, revolutionizing air transport. When converted to the military version, designated the C-47, it was widely used in World War II.

During the 1930s and 1940s, passenger aviation made important strides, but there was a significant drawback. The 247 and the DC-3 could only fly as high as 10,000 feet, due to the reduced levels of oxygen at higher altitudes. Flying higher would allow airliners to rise above air turbulence and storms prevalent at lower levels.

The breakthrough came with the Boeing 307 Stratoliner, which began service in 1940 with TWA — Trans World Airlines. Derived from the B-17 bomber, it was the first aircraft with a pressurized cabin. The 33-seat Stratoliner flew as high as 20,000 feet and could travel at 200 mph.

During the Second World War, the NACA also made numerous crucial contributions sometimes referred to as “the force behind our air supremacy.” Most notably, the agency played key roles in producing innovative superchargers, providing more efficient engines for high altitude bombers and improved technology for wings.

Following the war, commercial aviation grew at a rapid pace with airlines regularly transporting passengers and cargo. This expansion was aided by wartime technology development such as that of heavy B-29 bomber airframes. The aviation industry also began transitioning from propeller aircraft to jets.

The first commercial jet airliner to fly was the British de Havilland Comet first flown in 1949. During the late 1950s, Boeing’s 707 and the Douglas DC-8 offered comfort and safety leading to extensive commercial jet air travel in the United States.

Dawn of the Space Age

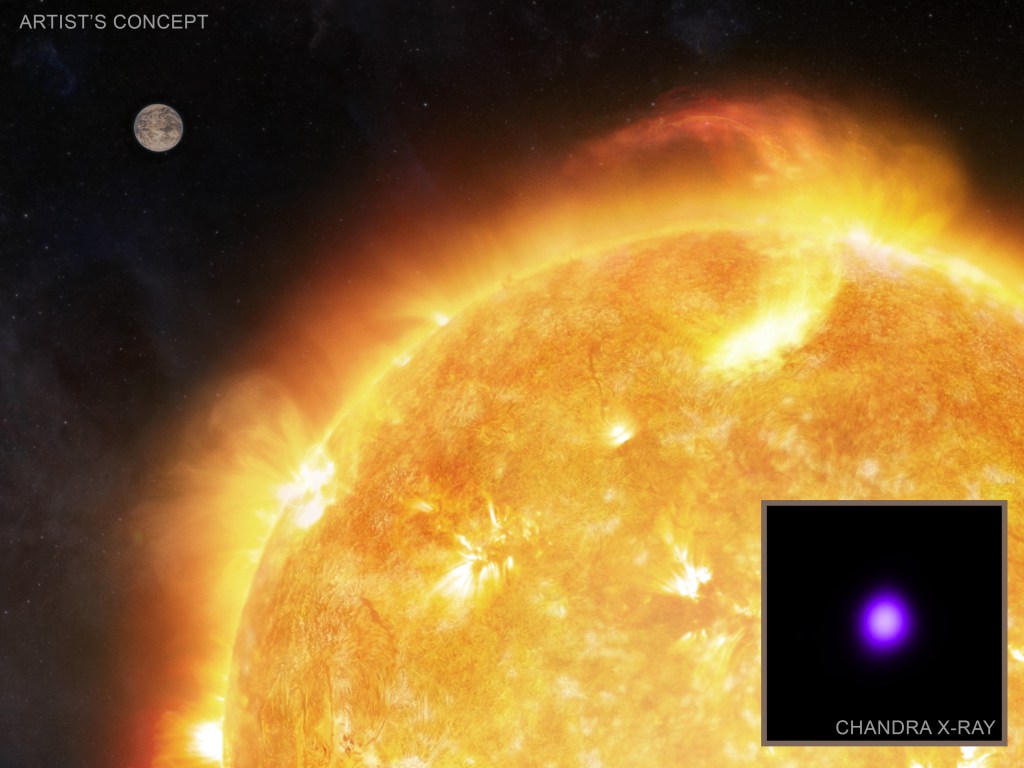

At about that same time, the space age began on Oct. 4, 1957, with the launch of the Sputnik satellite by the Soviet Union. An American satellite, Explorer 1, soon followed, with plans for sending humans into space in the near future.

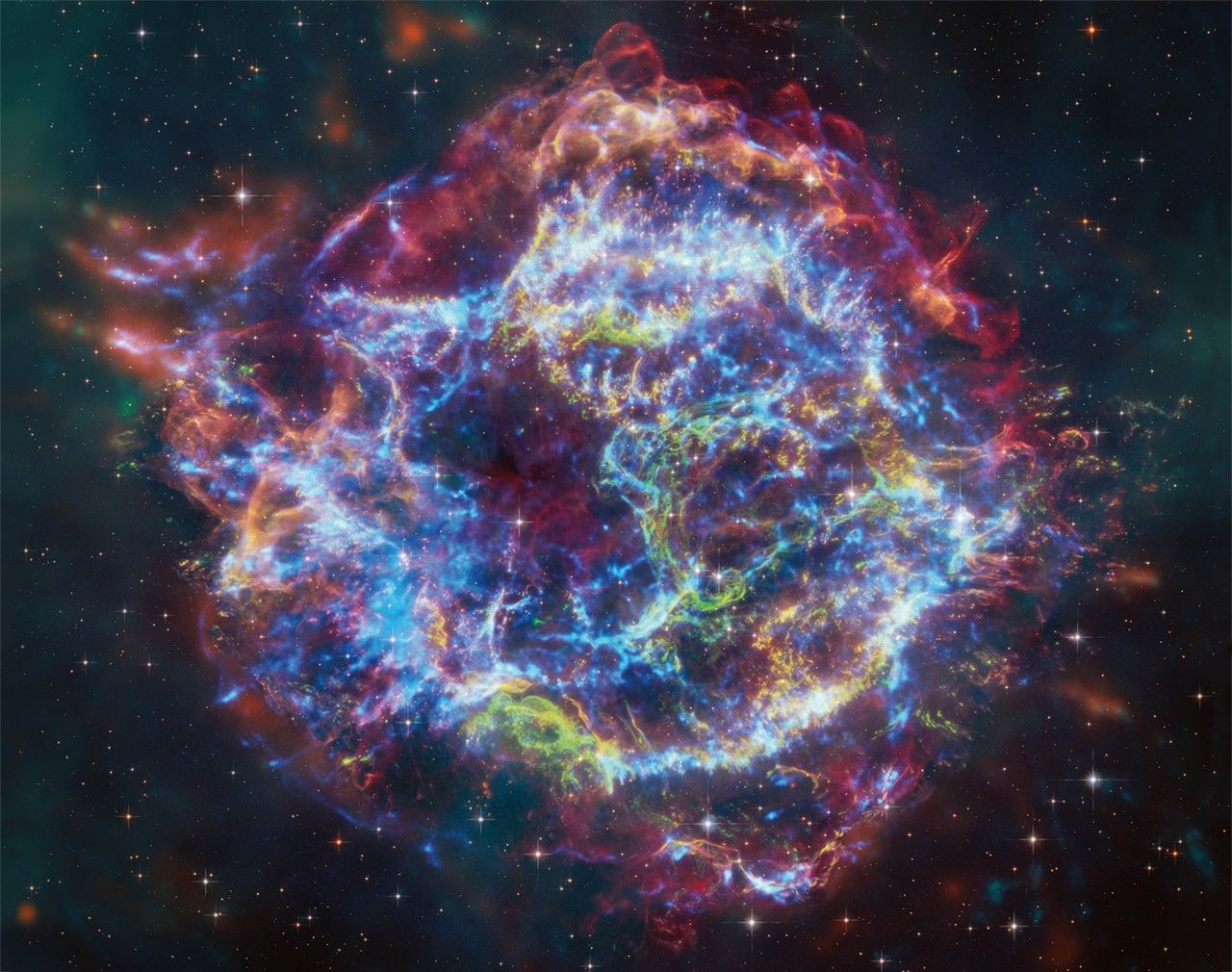

In the midst of these advances, President Dwight Eisenhower directed the NACA to be reorganized on Oct. 1, 1958, forming NASA — the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

“(There are) many aspects of space and space technology,” he said, “which can be helpful to all people as the United States proceeds with its peaceful program in space science and exploration.”

As was the case with early aviation, American industry partnered with the government to advance spaceflight technology. Many of the same aerospace corporations that took the nation to the skies began supporting the new space agency’s efforts to explore beyond the atmosphere. Contractors developed the launch vehicles and satellites to study the Earth, probes to explore beyond low-Earth orbit and spacecraft to take the first humans into the new frontier.

Airlines Double Down

During 1969, the year astronauts first walked on the moon, America’s aerospace industry debuted wide-body passenger airliners such as the Boeing 747.

Pan American Airways was the first to purchase and fly the 747 jumbo jet. It had two aisles and an upper deck over the front section of the fuselage. With a capacity of 450 passengers, it doubled the size of other Boeing jets and was 80 percent larger than any other jetliner up to that time.

McDonnell Douglas soon answered with their DC-10 in 1970, and Lockheed entered the wide-body market with the L-1011. Both had three engines, one under each wing and one on the tail, and each had a seating capacity of about 250.

In addition to flying more passengers in enhanced comfort, in the late 1960s airlines began to focus on increased speed. The NACA played a key role proving that it was possible to fly faster than the speed of sound – about 768 mph. In 1947, the Bell X-1 had broken the sound barrier, but there still were obstacles for a commercial supersonic transport.

The Soviet Union successfully developed and tested the supersonic Tupolev 144 in late 1968. A consortium of West European aerospace firms flew the Concorde in early 1969 and eventually produced a number of those fast airlines for commercial use. American efforts to produce supersonic transports stalled in 1971. The primary concern was the sonic boom produced by these aircraft.

A sonic boom occurs when an object travels through the atmosphere faster than the speed of sound. It creates shock waves generating enormous energy sounding like an explosion.

Developments of commercial aviation have had a world-wide financial impact. According to the website of the travel publication “Jet Set Times,” the global aviation industry annually supports 57 million jobs and $2.2 trillion in economic activity. In a 12 month period, 50 million tons of cargo are flown by air transport aircraft, accounting for $6 trillion in goods equating to 35 percent of all products traded internationally.

Rise of Commercial Spaceflight

Early developments in aviation were dominated by individuals working privately. This later was followed by governments and industry. However, in the first eras of space exploration, costs and risks were borne solely by government agencies, both military and civilian.

But now that NASA and other agencies have greased the skids, opportunities for space tourism also are on the verge of becoming a reality for recreational or business purposes.

In the late 1990s, MirCorp was responsible for operation of the Russian space station Mir, and began seeking tourists willing to pay for a trip into space. American businessman Dennis Tito, a former scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, entered into an agreement with MirCorp and U.S.-based Space Adventures Ltd. Tito become the first “fee-paying” space tourist visiting the International Space Station in April 2001, staying for seven days.

Established in May 1996, the Ansari X Prize was a competition offering $10 million to the first non-government organization to launch a reusable, piloted vehicle into space twice within two weeks. Designed to encourage development of low-cost spaceflight, the concept was modeled after early 20th-century aviation prizes.

On June 21, 2004, SpaceShipOne made the first privately funded human spaceflight. The spacecraft was developed by Mojave Aerospace Ventures, a joint enterprise between Scaled Composites, an aviation company founded by test pilot Burt Rutan and Microsoft founder Paul Allen. The second flight was Sept. 29, 2004. Five days later, SpaceShipOne’s developers won the X Prize by reaching 62 miles in altitude twice in a two-week period. The 62-mile mark is recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (International Aeronautical Federation) as the threshold of space.

The success of SpaceShipOne led to Virgin Galactic forming a company designed to provide suborbital spaceflights aboard SpaceShipTwo to launch space tourists, suborbital flights for space science missions and orbital launches of small satellites.

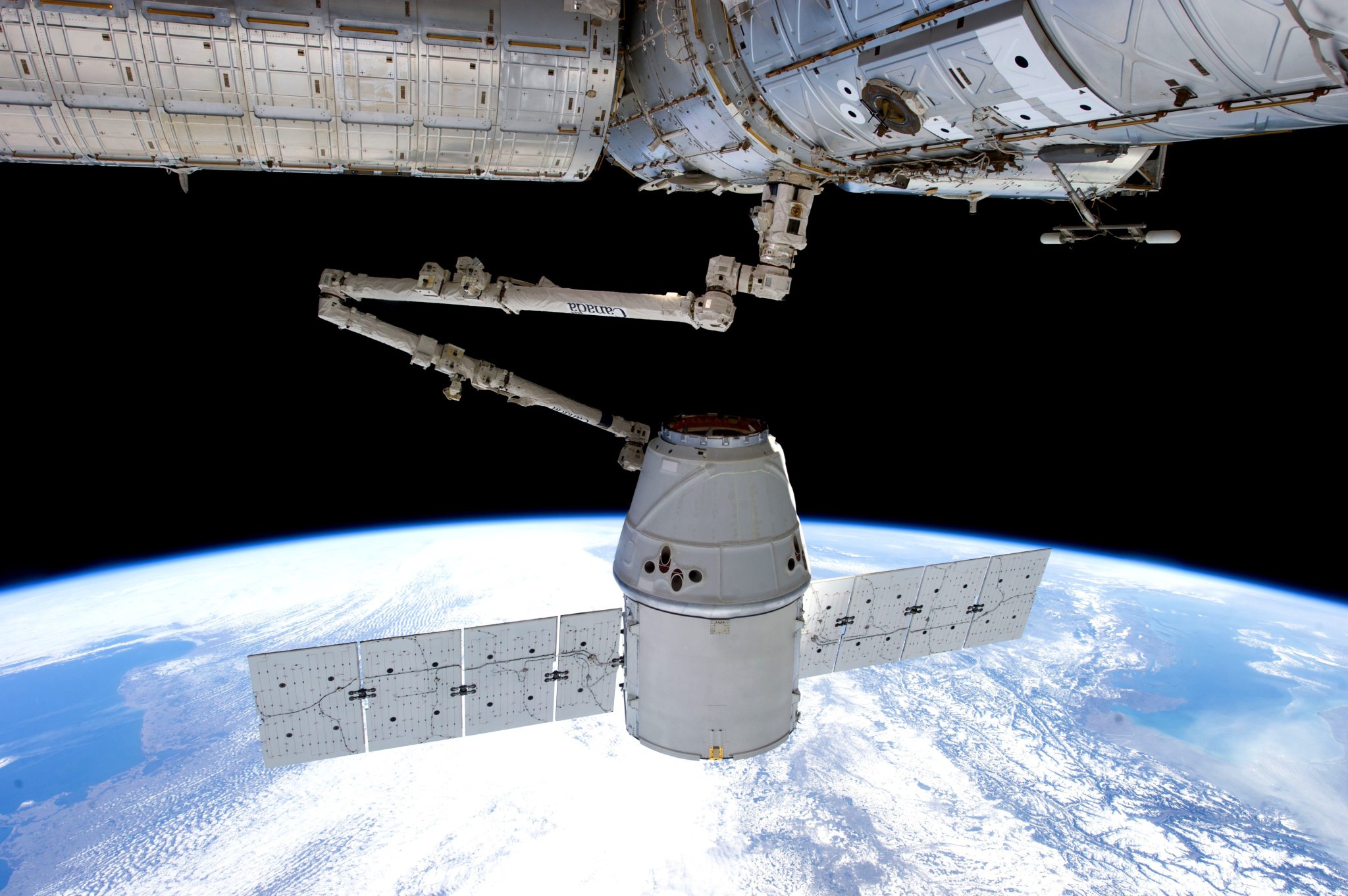

NASA’s commercial space program has fostered a successful partnership between the agency and two American companies to resupply the International Space Station. Following the end of the Space Shuttle Program, SpaceX and Orbital ATK began providing resupply spacecraft launching cargo and supplies to the ISS through the Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) Program.

In the near future, commercial spaceflight not only will include supplies, but also humans.

“American companies are developing the new systems in which astronauts soon will travel from the United States to low-Earth orbit,” said NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden during remarks at Kennedy on Feb. 2, 2015.

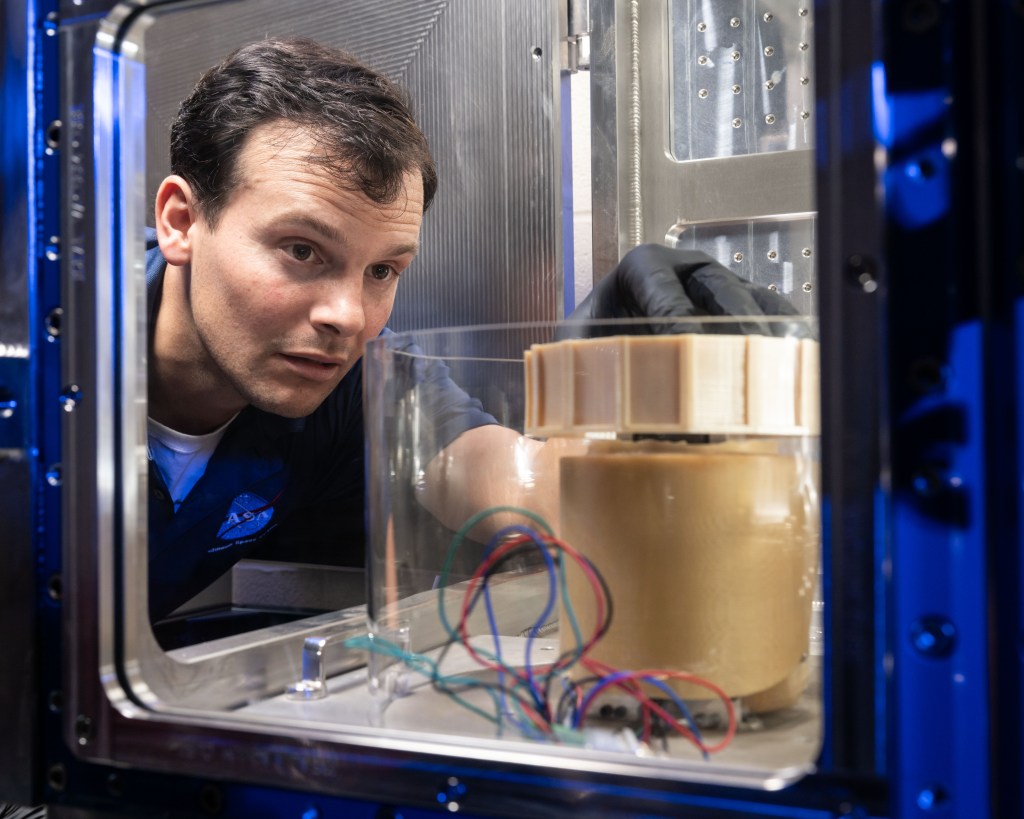

In September 2014, the agency announced the selection of Boeing and SpaceX to transport U.S. crews to and from the International Space Station using their CST-100 Starliner and Crew Dragon spacecraft, respectively. The goal is for U.S. missions to the station to end the nation’s sole reliance on Russia in 2017, and allow the station’s current crew of six to grow, enabling more research aboard the unique microgravity laboratory.

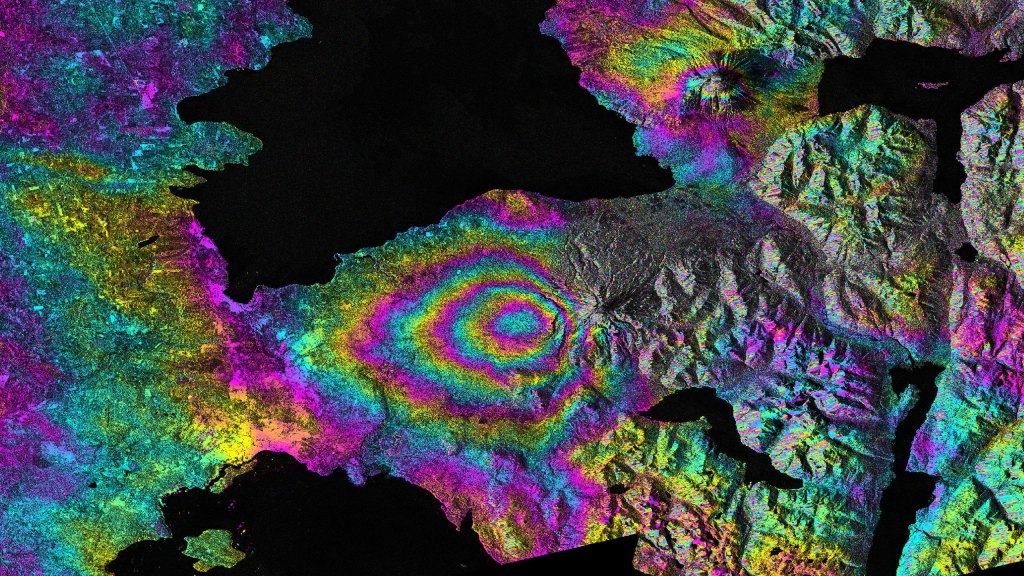

By allowing industry to provide “taxi” services to the space station, NASA now can concentrate on exploration to distant destinations such as a near-Earth asteroid and Mars.

At the same time, the agency also is teaming with industry and academia in developing future aircraft that conserve fuel, lower emissions and reduce noise.

Since the sound barrier first was broken in 1947, aviation experts have sought ways to limit the jarring effects of the sonic booms. One of NASA’s primary aeronautical goals is to work with the aerospace industry to develop aircraft that achieve a low or quiet enough boom that a current federal ruling prohibiting supersonic flight over land might be lifted.

Over the past century, pioneering inventors and entrepreneurs in aerospace have been driven by inspiration and supported by those who backed their efforts to go faster, higher and farther.

“We were lucky enough to grow up in an environment where there was always much encouragement to children to pursue intellectual interests,” said Orville Wright. “We investigated whatever aroused curiosity.”

Today, NASA is trying to instill these same values with the vision to reach new heights, reveal the unknown, while benefiting all humankind.

Pioneers Found Novel Approaches to Early Commercial Aviation

By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

Some of the pioneering entrepreneurs of aviation found novel approaches to making use of the new technology.

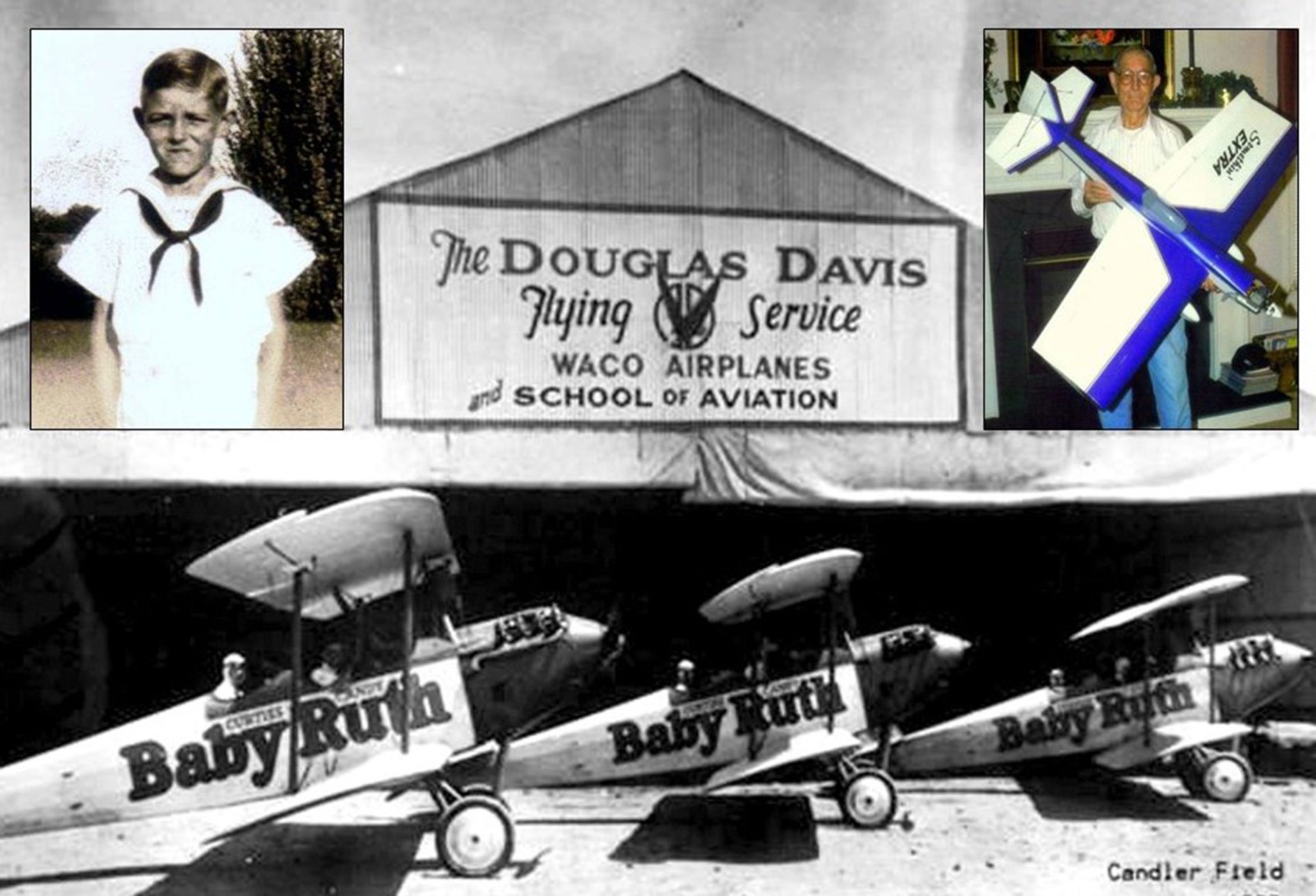

In the 1920s, Atlanta opened an airport seeking to secure a lucrative contract for one of the new air mail routes. One of the first to open for business at the new air field was Georgia native Doug Davis. The World War I aviator and barnstormer started the Douglas Davis Flying Service with the first airport hangar at what then was called Candler Field. Today it is the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.

In 1924, Davis was selected by the Curtis Candy Co. to form the Baby Ruth Flying Circus to advertise the new chocolate bar. The plan was to fly over large crowds during outdoor events and drop hundreds of samples attached to tiny parachutes. However, this approach required an assistant to pitch the candy bars overboard while Davis flew the airplane.

One of those Davis enlisted was an 11-year-old boy who loved aviation and frequently dropped by the new Atlanta airport to talk to some of the pilots who worked there.

That youngster was my father, Buster Granath.

After getting permission from Granath’s parents, Davis strapped the wide-eyed aviation enthusiast on a cushion in the back seat of a bi-plane. Granath didn’t recall what event brought together the crowd that would be the target for the candy drop.

“At that age, it was the most exciting thing I’d had the chance to do,” Granath said. “It was great just having the chance to fly.”

Over the next eight years, Davis repeated the process in 40 states, usually with the assistance of young aviation buffs such as Granath.