NASA’s Cassini spacecraft arrived at Kennedy Space Center 20 years ago to begin processing for launch on a mission that would see it deliver spectacular images and data from the ringed planet Saturn. As the massive spacecraft begins its final chapter, engineers at Kennedy took a look back to how their contributions to the mission began.

The processing and launch of NASA’s Cassini spacecraft in 1997 gave engineers at Kennedy Space Center in Florida a chance to work with a flagship spacecraft, new rocket and demanding power source. The Cassini mission also showed Kennedy launch teams techniques and approaches that would continue to pay off years later when new spacecraft were launched on unique missions.

Before heading to Saturn to conduct unprecedented science in the orbit of the gas giant, the Cassini spacecraft made a comparatively short jaunt from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, to Kennedy inside an Air Force C-17 transport aircraft. April 1997 saw the arrival of Cassini and its move to the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility for assembly.

“I’m thinking, ‘this is a very, very large spacecraft,’ ” said Omar Baez, who worked as a mechanical and propulsion systems engineer for the Titan IVB rocket that launched Cassini.

Standing about 22 feet tall and weighing almost three tons empty, the spacecraft was tested extensively during processing. The Huygens spacecraft, which was much smaller and laden with a wide assortment of instruments, was attached to the side of Cassini so it could separate and parachute to the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan.

“This was a whole new level of complexity and interest that got my attention,” said Ken Carr, one of the launch site integration managers for Cassini. “It’s mind-boggling the technology required to pull that off. We’re trying to accomplish pretty bold things and wondering whether we’re going to be able to pull it off at the end of the day.”

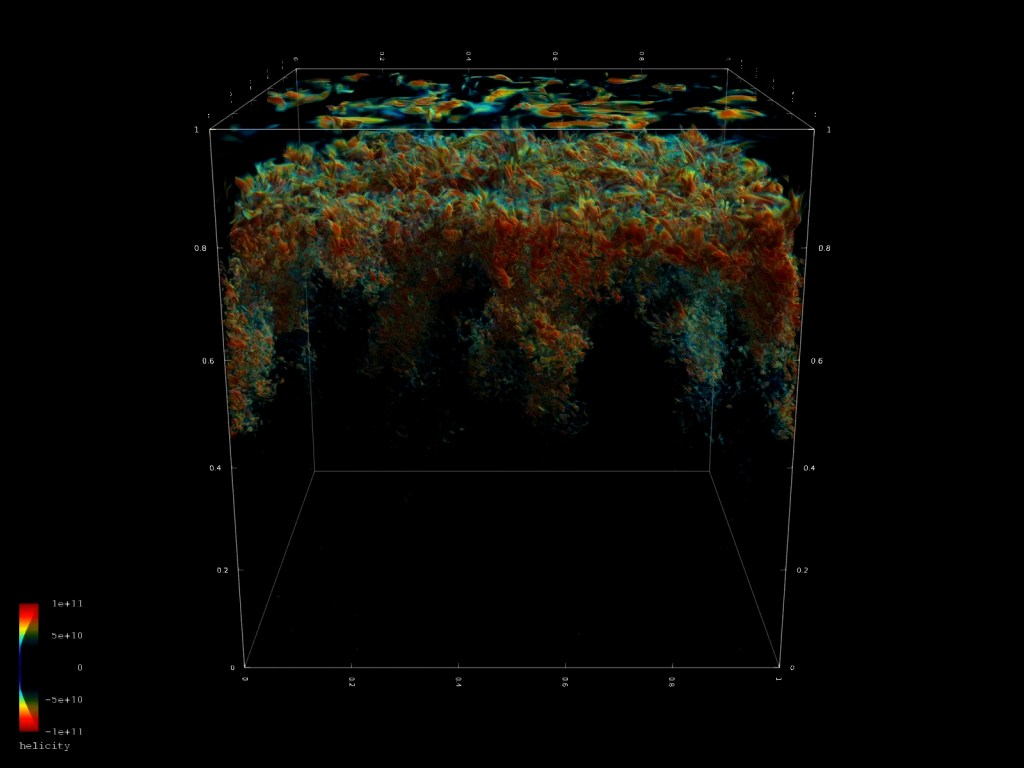

A great deal of attention was paid to Cassini’s power source, too. Plutonium encased in a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, or RTG, has provided electricity to Cassini throughout its 20 years in space, to power everything from navigation systems to the cameras and instruments that look closer at Saturn than ever before.

Ahead of the launch, every step of the handling of the RTG was not only planned carefully, but rehearsed repeatedly, sometimes months before the spacecraft arrived in Florida.

“I had to route all the hazardous procedures get them signed off on before the procedure was done and there many procedures that had to be written,” Carr said.

“When you’re flying material like that, you have to team with a lot of people,” Baez said. “I remember going to meetings and there were hundreds of people. Air Force, aerospace community, we had to deal with Glenn Research Center. There were tons of people at these meetings whereas now if we had similar meetings there would be 20 people. It was a big deal.”

Launch took place Oct. 15, 1997, when the Air Force Titan IVB ignited to catapult the robotic Cassini spacecraft on a path that would carry around the inner solar system to build up momentum and sling it out to Saturn.

“The last five minutes was complete silence in that control room,” Baez said. “It was a very cloudy morning and I remember seeing that Titan IV just shoot through the clouds on the way to Saturn. Everybody breathed a sigh of relief. We were able to exhale and relish in it.”

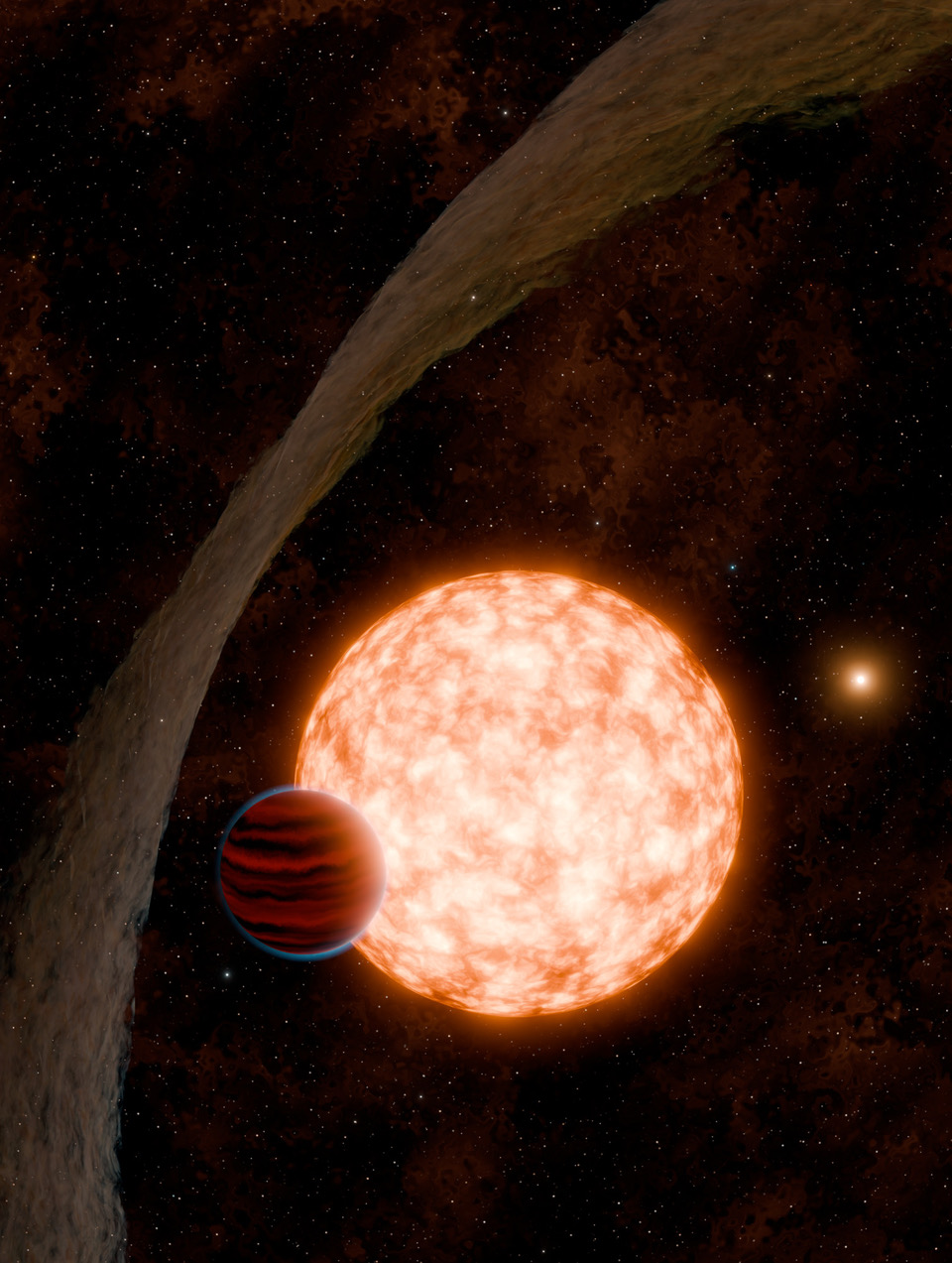

The spacecraft reached Saturn’s orbit on June 30, 2004, and began a tour of Saturn and its moons that returned remarkable images and detailed readings of the planet and its signature rings. Huygens landed on Titan in January 2005 and transmitted images from its surface. It was the first time a spacecraft landed anywhere in the outer solar system.

“Before, what we got was grainy and now we were getting these detailed photos in color,” Baez said. “It looked like somebody had drawn them. It just went from being two-dimensional to something real that you could almost grab.”

Cassini has been broadcasting new photos and scientific readouts from Saturn’s orbit in all the years since arriving. On April 26 it will perform its first dive between Saturn and its innermost ring to reveal some of the secrets behind the captivating planet’s unique appearance. The mission will end Sept. 15 when Cassini follows its trajectory into Saturn itself, so that it doesn’t accidentally contaminate any of the moons around the planet.

Cassini’s legacy will not end in September, however. Scientists still have data to pore over at multiple research facilities, including the mission’s home at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. In Florida, the launch teams for NASA’s Launch Services Program continue to draw lessons from Cassini as they prep for new missions.

“One thing that comes to mind is teamwork,” Carr said. “Here at NASA, we do teams well.”