Use it or lose it: It’s a fact of life for muscles – for you and me, for an astronaut, especially, and even for a tiny worm in space.

When people spend long periods of time in space, where gravity doesn’t weigh them down, their muscles can suffer from lack of use. The same is true for a minute organism that helps NASA understand the biology of our bodies away from Earth: a worm so small five of them could lie end to end next to a grain of rice.

Scientists are about to learn more precisely what causes space-related loss of muscle strength in this type of worm, called C. elegans, thanks to a biology experiment starting soon on the International Space Station. This is a step toward treating the same problem in future human explorers, because – small and wiggly as it is – the worm’s muscles work enough like a person’s to tell us some ways human health might be affected on longer missions into deep space.

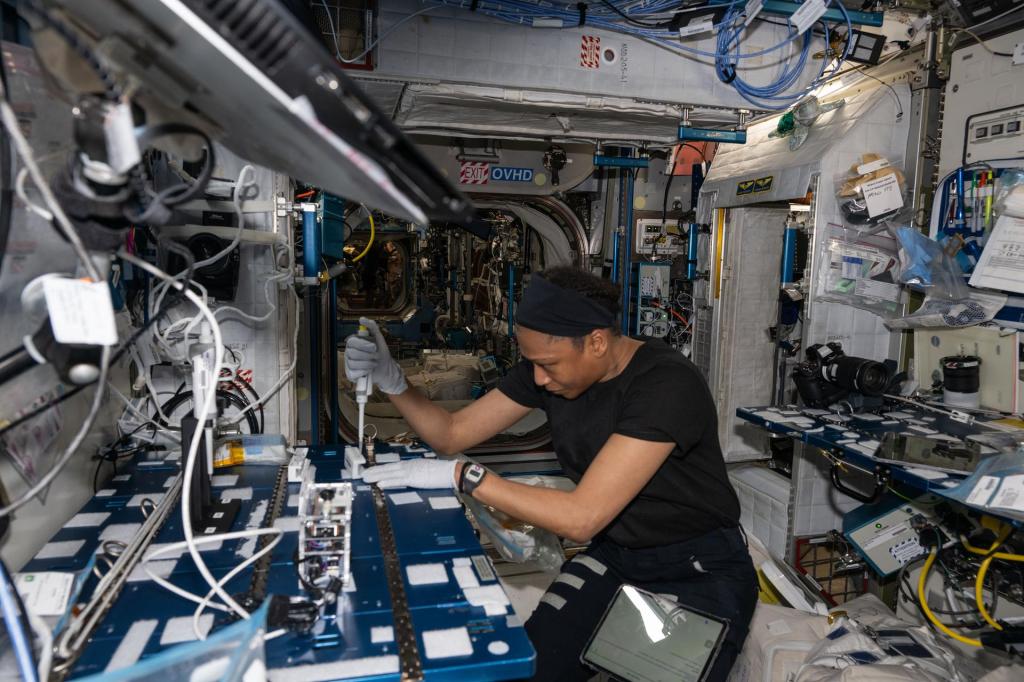

People have lived and worked on the space station continuously for 20 years now, testing technology and conducting experiments for researchers back on Earth. With this latest study, called Micro-16, scientists will look at changes in the way these worms, bred in microgravity, make and use muscle proteins, and see if they lead to changes in muscle strength.

They’ll also track changes in the worms’ strength and muscle-related genes across seven generations, revealing more about how muscles adapt to microgravity in both the short and long term. Of course, we don’t yet have multiple generations of people living in space to study, so Micro-16 will offer a unique opportunity to study how microgravity affects muscle strength and function.

Space Worms Hit the Gym

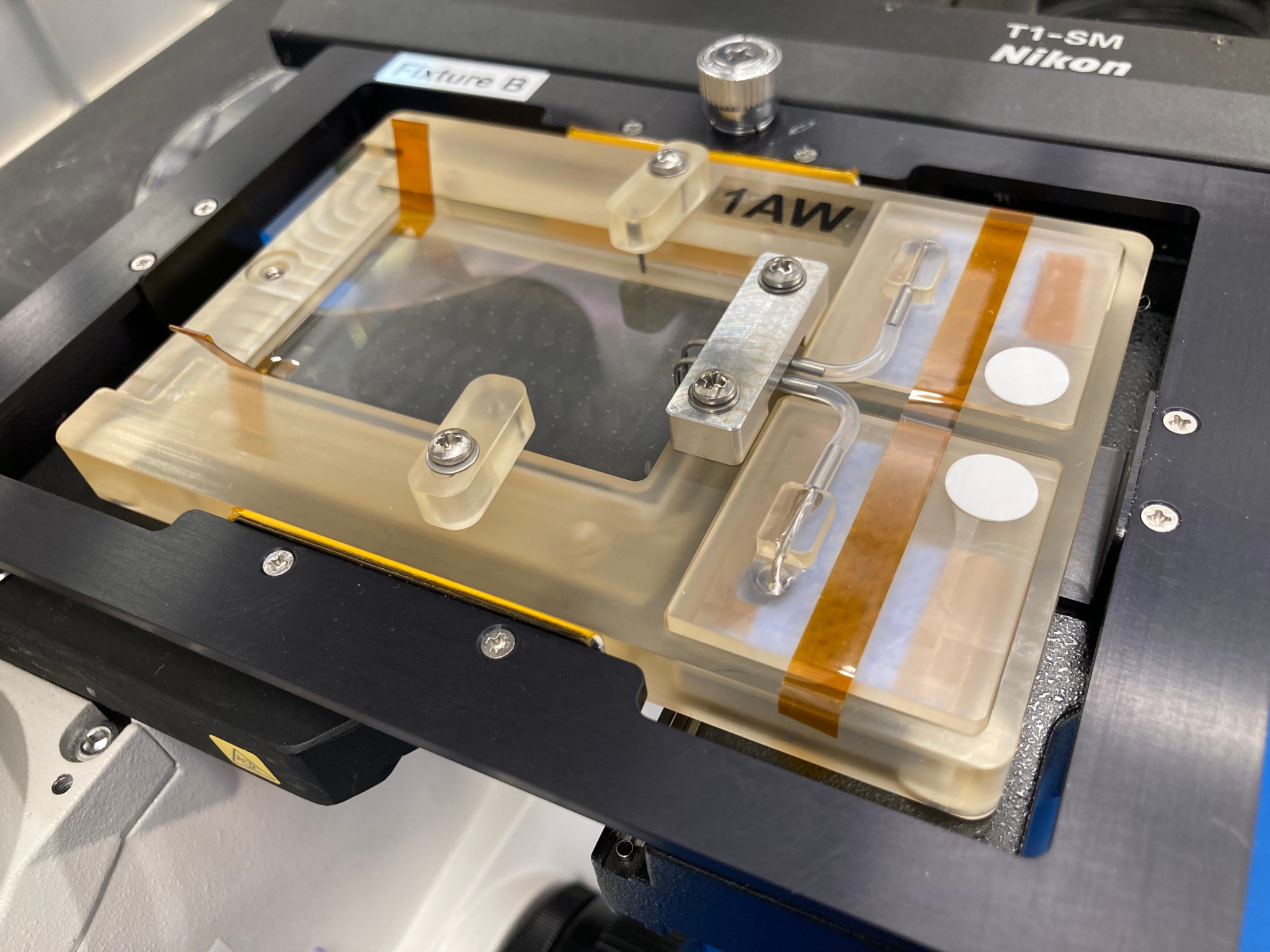

So, how do you measure the strength of a worm that is about one-fifth the length of a rice grain? The Micro-16 science team, based at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas, and Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, invented hardware, called NemaFlex, for just that purpose, and they’re about to test it in space for the first time.

Inside a special imaging compartment, the worms will wriggle through a dense forest of miniature, bendable pillars. As they move, a microscope’s camera will record how much each pillar bends away – a measure that reveals the muscle force with which each worm is pushing against them.

The C. elegans worm has been studied in great detail, making it a good candidate for research working out the intricacies of our shared biology. Studying its muscles in the space environment could make the comparison with humans even more informative for questions of astronaut performance – and help us out back on this planet. As the tiny worms muscle in on this spaceflight experiment, researchers hope the knowledge they gain will help reveal the best ways of keeping astronauts strong and new treatments for serious muscle disorders on Earth.

Micro-16 will launch on Northrop Grumman’s 15th commercial resupply mission to the International Space Station. The experiment is sponsored by NASA’s Space Biology program in the Division of Biological and Physical Sciences. The principal investigator is Siva A. Vanapalli of Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. BioServe Space Technologies of Boulder, Colorado, is the payload developer. NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley provided technical monitoring and mission management.

For researchers:

NASA Ames Biosciences Division – Micro-16 experiment page

International Space Station – Micro-16 experiment page: Determining Muscle Strength in Space-flown Caenorhabditis elegans

For news media:

Members of the news media interested in covering this topic should reach out to the NASA Ames newsroom.