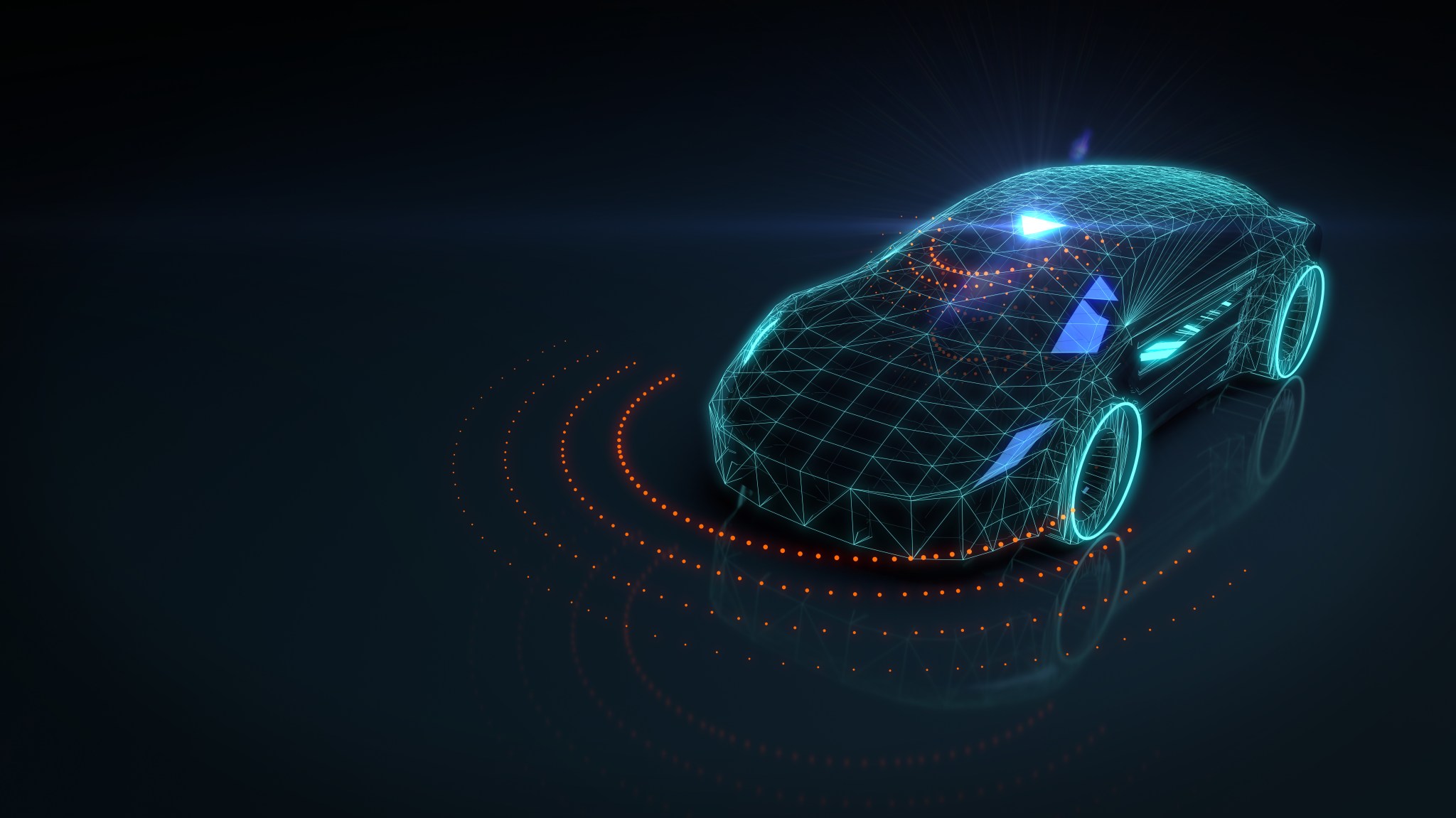

Drowsy driving accounts for a large proportion of car crashes, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. So, you might think self-driving cars would fix that. After all, computers just don’t get sleepy.

But today’s vehicles are only partially automated, requiring the human driver to stay alert, monitor the road, and take over at a moment’s notice. A new study conducted by the Fatigue Countermeasures Lab at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley suggests this passive role can leave drivers more susceptible to sleepiness – especially when they’re sleep deprived.

The research was carried out to help understand how humans interact with autonomous systems, such as those used in aircraft and in spaceflight systems. The findings will contribute to the agency’s research around the safe introduction of automation in aviation and the growing complexity of advanced systems. They also suggest drowsy drivers may be an important consideration for safe introduction of self-driving features in cars.

Drivers Pave the Way for Pilots and Astronauts

NASA’s Fatigue Countermeasures Lab is primarily interested in sleep, or the lack thereof, as it concerns pilots and astronauts, who may be fighting fatigue when carrying out complex tasks on the job. Autonomous systems are becoming more common in both aviation and spaceflight, and some pilots report using autopilot as backup when coping with sleepiness during a flight.

Knowing that our ability to keep monitoring an uneventful situation goes down when we’re sleep deprived, researchers wanted to understand how this might affect the use of autopilot. Since driving is, in many ways, a similar task to flying and drivers are a lot more common than pilots, the lab decided to study them first.

The team looked at whether people on their ordinary sleep schedules would show more sleepiness supervising a self-driving vehicle, compared to manually controlled driving. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that many people across the country don’t get enough sleep, and study participants had the same range of habits as the general population. Many of them got much less than the recommended seven to eight hours of sleep per night in the week before the study.

Participants in three separate experiments completed two 48-minute sessions in a driving simulator. In one condition, they had full control of the simulator’s steering wheel, gas pedal, and brake. In another, they used self-driving mode and had no control of the vehicle dynamics but were instructed to keep their hands on the steering wheel while monitoring the vehicle. On a screen in front of them, all participants saw a flat, monotonous, two-lane road in the countryside roll by, with little traffic and no stop signs or traffic lights.

The drivers wore electrodes during both sessions to monitor brain activity and eye movements characteristic of falling asleep. Immediately following each drive, they rated their sleepiness on a standard scale and completed a test to evaluate attention.

The results showed that, when supervising – rather than actively operating – the vehicle, participants reported feeling sleepier and showed increased signs of “nodding off.” They also showed slower reaction times compared to actively driving the car. And the more sleep deprived a person was, the stronger these effects were.

“The bottom line is not that self-driving cars are more or less safe than manually driving,” said Erin Flynn-Evans, director of the Fatigue Countermeasures Lab. “It’s that when people don’t get enough sleep, they are vulnerable in both driving scenarios.”

Fatigue in Flight and on the Road

Now that they understand more about the relationship between fatigue and people’s ability to keep tabs on an autonomous system, the researchers will apply this knowledge to their work in aviation. Future studies could include working with pilots using flight simulators and, later, on actual flights.

Since astronauts, too, will likely have highly automated procedures for the Artemis lunar missions and eventual Mars missions, NASA is using this study to help design such procedures and related policies, including scheduling enough time for those astronauts to sleep.

“Our goal is to help NASA understand where there are important targets for future research concerning pilots and astronauts,” said Flynn-Evans. “We hope that our work will help the research community understand how people’s ability to monitor a situation is different from their ability to actively engage in it.”

The findings have implications for commercial truckers and others whose vehicles are using more and more automation. The results also highlight the need to continue studying fatigue and safety in partially autonomous systems. As the operator’s role shifts to one of passive supervision, solutions could be developed to help sleepy drivers stay engaged and alert. Meanwhile, everyone driving should make sure to get enough sleep until, one day, fully autonomous vehicles may be ready to take the wheel.

For news media:

Members of the news media interested in covering this topic should reach out to the NASA Ames newsroom.

Author: Abby Tabor, NASA’s Ames Research Center