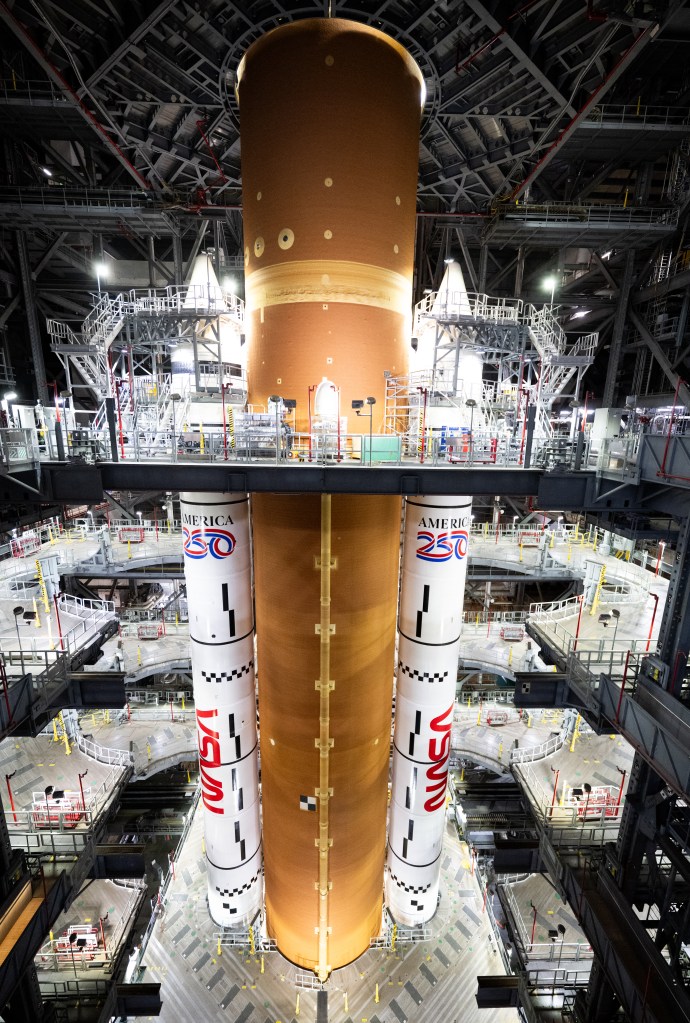

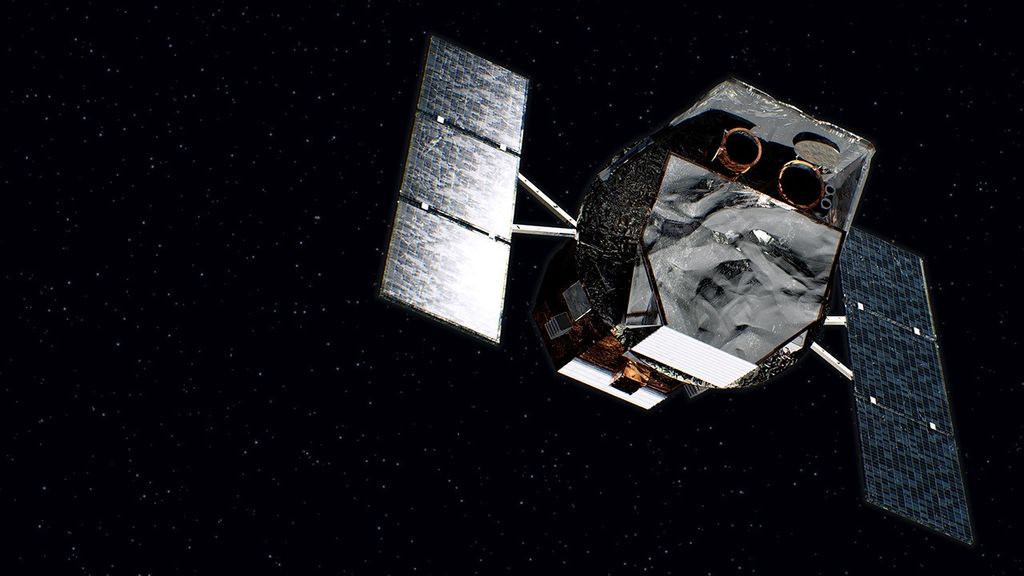

When Artemis I launched on Wednesday, Nov. 16, NASA’s new mega Moon rocket carried the Orion spacecraft – uncrewed, for now – into orbit for the first time, and a new era of lunar exploration began. It’s a big moment for NASA and the world. And, yet, one of the people whose work will be tested at the next crucial step – bringing Orion home safely – isn’t nervous at all.

Jeremy Vander Kam is the deputy system manager for the Orion spacecraft’s thermal protection system (TPS) at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. He leads the team that developed the heat shield and thermal tiles that will protect Orion from the extreme high temperatures the spacecraft will meet on its way home.

“Orion will come blazing through Earth’s atmosphere at temperatures twice as hot as molten lava,” said Vander Kam. “But everything points to a thermal protection system that’s going to work great, and a successful homecoming will help confirm the heat shield is ready to protect astronauts returning to Earth.”

That’s a big responsibility, but, for Vander Kam, this moment isn’t nerve-wracking. He’s just excited the big day is finally here.

A Thousand Tests Strong

After traveling beyond the Moon, nearly 270,000 miles from Earth, the capsule will work up a speed of 25,000 miles per hour. As it slams through Earth’s atmosphere, friction will cut that speed to just 300 miles per hour in a matter of minutes. The result is heat – and a lot of it.

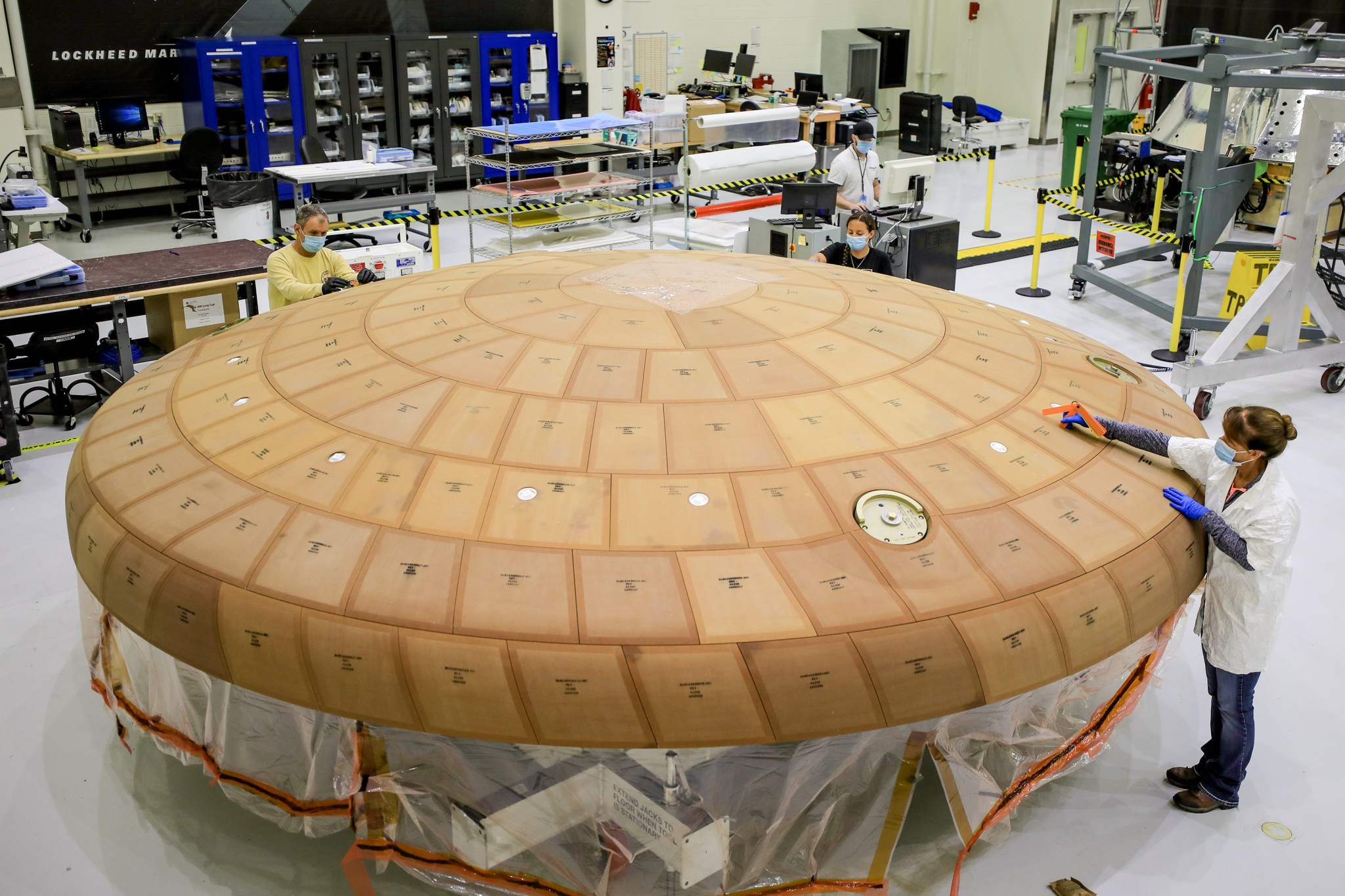

The Apollo crew module’s heat shield relied on a material called Avcoat to beat the heat. It’s an ablator, meaning it burns off in a controlled fashion during re-entry, transferring heat away from the spacecraft. A new system of Avcoat tiles just one to three inches thick is used to cover the Orion heat shield’s external surface. This is what will make the difference between 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit on the front and a mere 200 degrees on the back side of the heat shield.

A second ablator material was also used in certain locations on Orion. Invented by Ames, the 3-Dimensional Multifunctional Ablative Thermal Protection System (3DMAT) is made of woven threads of quartz in resin. It’s stronger than Avcoat and was included to strengthen connection points along the spacecraft.

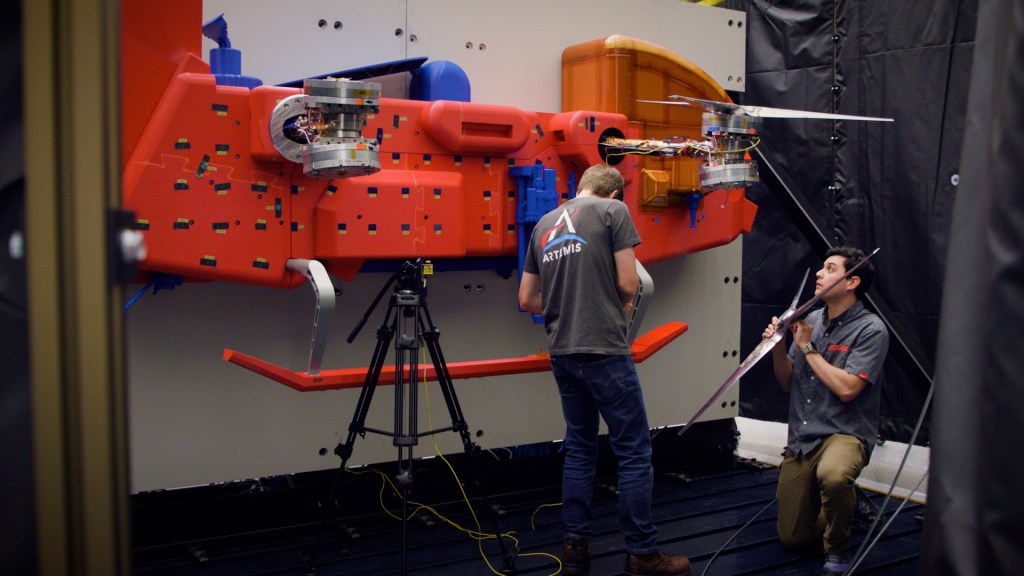

Vander Kam’s confidence in the system comes partly from extensive testing of the thermal protection materials. In the arc jet facilities at Ames, where incredibly hot, fast-moving gases mimic the conditions of atmospheric entry, the TPS team performed more than 1,000 tests.

A Data-Rich Return

Orion’s re-entry on Sunday, Dec. 11 will offer the ultimate test of the TPS team’s work. Vander Kam will be waiting aboard a U.S. Navy ship off the coast of San Diego to participate in recovery of the spacecraft once it splashes down in the Pacific Ocean.

A primary goal of Artemis I is to certify the Orion heat shield for use on flights with astronauts. Some data needed for that decision will come from sensors embedded in the Avcoat material. Ames-built instruments will measure the temperatures the heat shield experiences, while sensors for pressure and radiation were contributed by NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, and the agency’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Following the Artemis I mission, the Ames team will also harvest samples of the charred Avcoat tiles to analyze how the material ablated.

Vander Kam expects to learn a lot from Orion’s flight data, which will also help confirm the accuracy of their computer simulations. These were created, in part, by colleagues at Ames to predict launch and re-entry conditions for the capsule.

Together, all this information could be used to confirm the design for the heat shield on future Artemis missions and, in the nearer term, to declare Artemis II “crew certified” to carry humans to the Moon.

On future Artemis missions, NASA will land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon – a goal Vander Kam is proud to support.

“This is a great milestone to achieve for humanity,” he said. “I think it’s important to remind us all to aspire to greater unity.”

Looking ahead to splashdown, Vander Kam is excited to listen for the sonic booms Orion should make while it’s still traveling faster than the speed of sound: the first clue that all is well with the capsule’s re-entry.

Then, the parachutes will come out, and he’ll watch the spacecraft glide to the ocean surface, thanks to the work of his team.

“It’s really cool to have gone through all these years with the same people,” he said. “It’s amazing getting to an accomplishment like this with my team. I expect to be emotional!”

He surely won’t be alone.

For news media:

Members of the news media interested in covering this topic should reach out to the NASA Ames newsroom.