Just 10 days after the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) opened for business on October 1, 1958, the new Agency launched its first satellite, Pioneer 1. Previously, other United States agencies made 13 attempts to launch a satellite, of which 4 were successful, but Pioneer 1 was the first under NASA management. The Agency inherited the Pioneer lunar program from the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), a branch of the Department of Defense established early in 1958 in response to President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s initiative to respond to early Soviet space accomplishments. The program consisted of five probes. The first three were lunar orbiters built by Space Technology Laboratory to be launched by the U.S. Air Force’s Thor-Able rocket. The last two involved simpler lunar fly-by spacecraft built by the U.S. Army’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and launched by the Army’s Juno II booster. NASA not only inherited the Pioneer program, but in December 1958 the Agency absorbed JPL.

The first Pioneer launch attempt on August 17, 1958, ended in failure 77 seconds after liftoff when the booster exploded. The problem with the rocket was identified and corrected, and on October 11, Pioneer 1, weighing 38 kilograms (84 pounds), thundered off from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 17A. Liftoff seemed to go well, but tracking soon showed that the spacecraft was traveling more slowly than expected and was also off course. Relatively minor errors in the first stage’s performance were compounded by other issues with the second stage, making it clear that Pioneer 1 would not achieve its primary goal of entering orbit around the Moon. The spacecraft did reach a then-record altitude of 113,830 kilometers (70,770 miles) about 21 hours after launch before beginning its fall back to Earth. It burned up on reentry over the Pacific Ocean 43 hours after liftoff. The probe’s instruments confirmed the existence of the Van Allen radiation belts discovered by Explorer 1 earlier in the year.

The third and final lunar orbiter attempt, Pioneer 2 on November 8, met with less success. The rocket’s first and second stages performed well, but the third stage failed to ignite. Pioneer 2 could not achieve orbital velocity and only reached a peak altitude of 1,550 kilometers (960 miles) before falling back to Earth after a brief 42-minute flight.

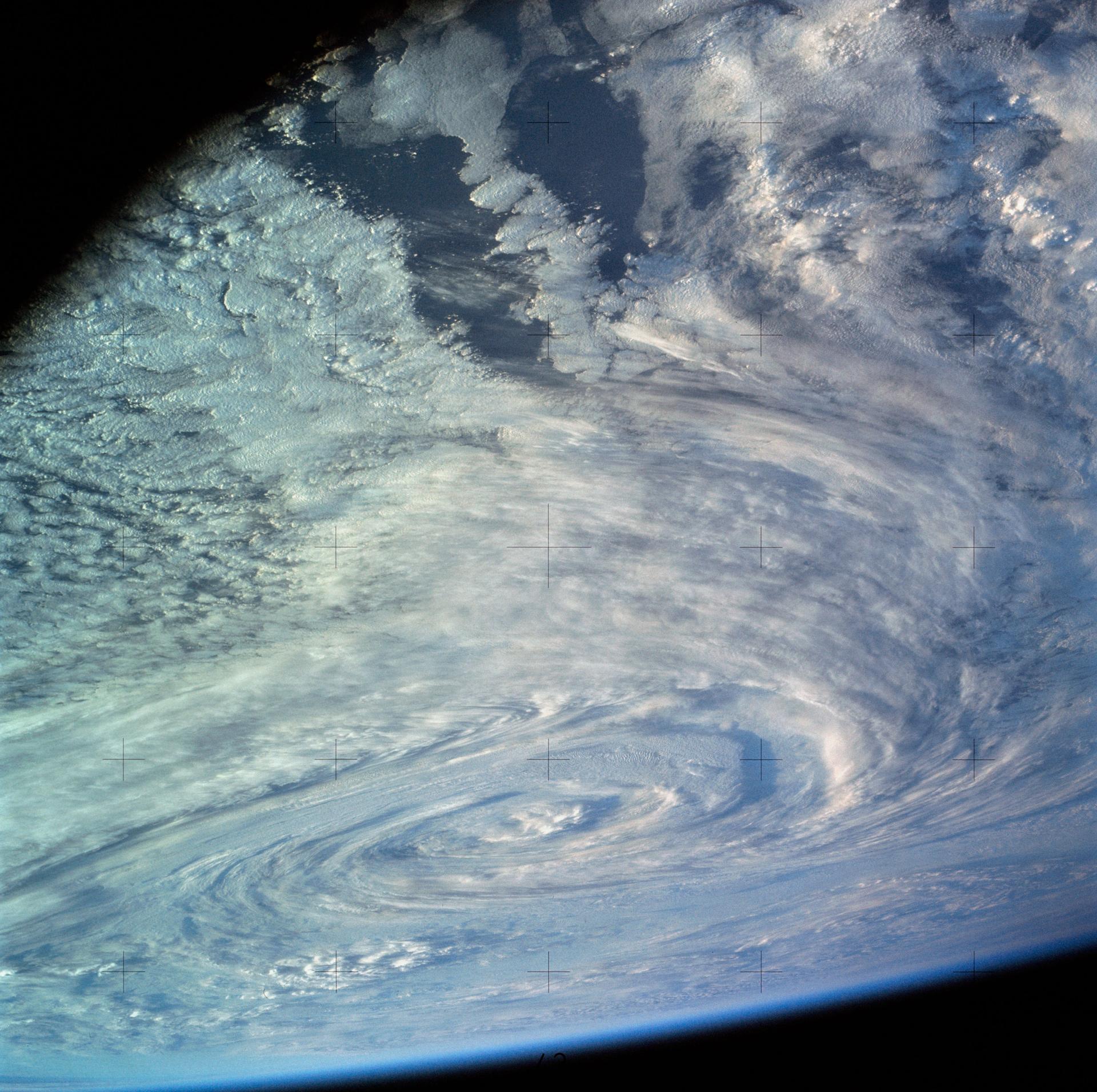

The two lunar flyby missions were next, and the 6-kilogram (13-pound) Pioneer 3 took off on December 6. The rocket’s first stage engine cut off early, and the probe was not able to reach its destination, falling back to Earth 38 hours after launch. Despite this problem, Pioneer 3 returned significant radiation data and discovered a second outer Van Allen belt encircling the Earth. The second attempt on March 3, 1959, was more successful and Pioneer 4 passed within 60,000 kilometers (36,650 miles) of the Moon’s surface. It then went on to become the first American spacecraft to enter solar orbit, a feat the Soviet Luna 1 accomplished the previous January. Pioneer 4 returned radiation data for 82 hours, out to 658,000 kilometers (409,000 miles), nearly twice the Earth-Moon distance.

Although these early Pioneer lunar probes met with limited mission success, the program marked the first use of the 26-meter antenna and tracking station at Goldstone, California. This antenna, completed in 1958 and known as Deep Space Station 11 (DSS-11), was the first component of what eventually became the NASA Deep Space Network (DSN). DSS-1 not only followed these early Pioneers, starting with Pioneer 3, but later monitored the Surveyor lunar soft landers (1966-1968) and tracked the Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle to the Moon’s surface on July 20, 1969.

Watch a video about Pioneer 4: