On May 16, 1963, NASA astronaut L. Gordon Cooper splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, completing the final mission of Project Mercury and the longest American spaceflight up to that time. His 22-orbit Mercury-Atlas 9 mission aboard the Faith 7 spacecraft lasted 34 hours and 20 minutes.

On May 16, 1963, NASA astronaut L. Gordon Cooper splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, completing the final mission of Project Mercury and the longest American spaceflight up to that time. His 22-orbit Mercury-Atlas 9 mission aboard the Faith 7 spacecraft lasted 34 hours and 20 minutes. He completed 11 experiments and overcame hardware anomalies to manually bring his spacecraft safely back to Earth. In his single mission, Cooper accumulated more spaceflight time than the other five Mercury flights combined, and gave NASA confidence to proceed to Project Gemini, during which astronauts demonstrated the techniques required to meet President John F. Kennedy’s goal to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth before the end of the decade.

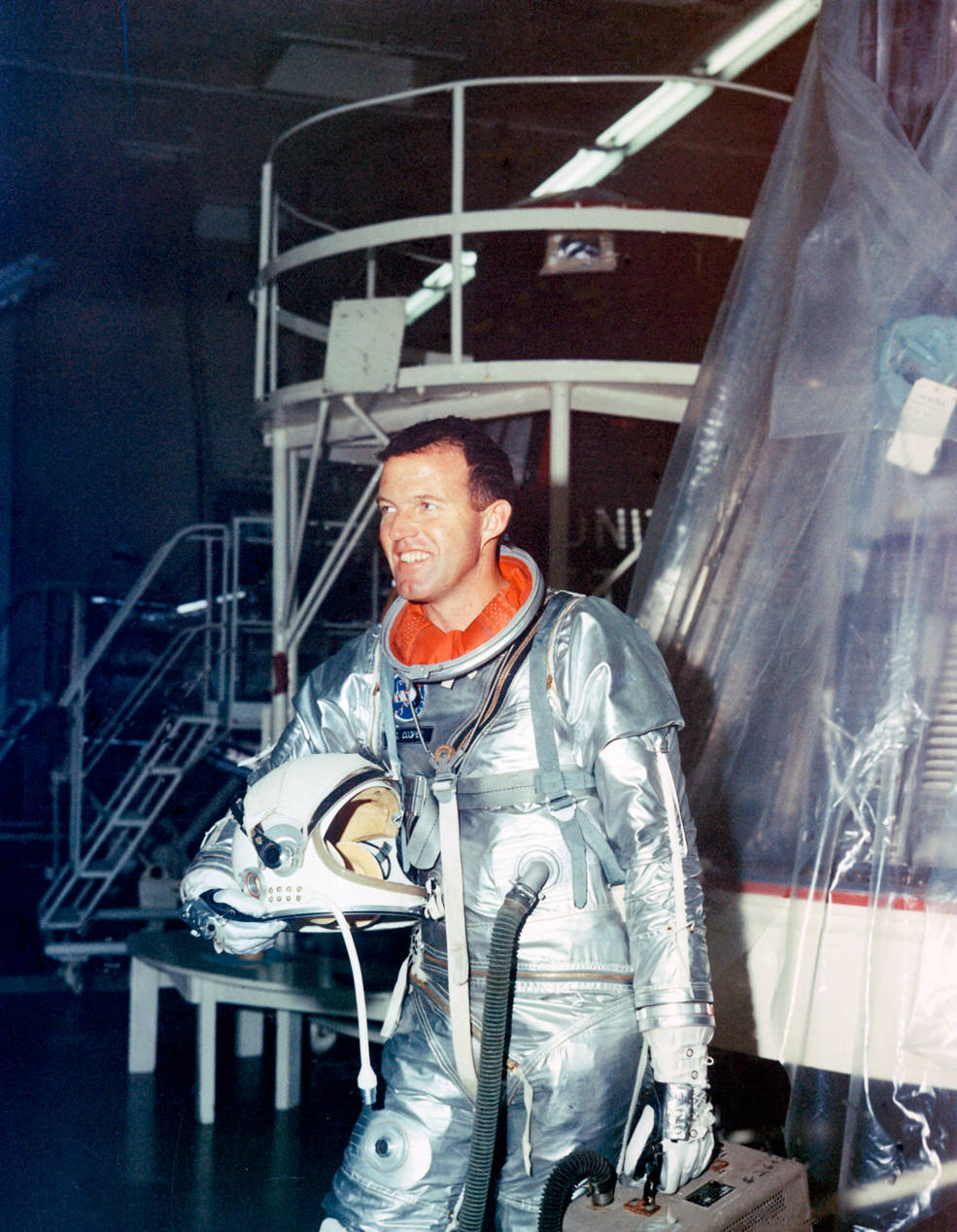

Left: Official NASA portrait of astronaut L. Gordon Cooper. Middle: Cooper during his preflight press conference. Right: During training, Cooper poses with his Mercury spacecraft.

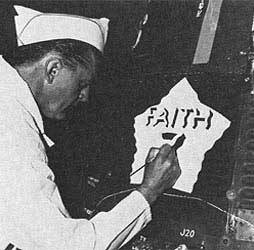

On Nov. 14, 1962, NASA announced that Cooper would fly the Mercury-Atlas 9 mission, with Alan B. Shepard, the first American in space, as his backup. The original plan called for an 18-orbit flight, but based on the success of Walter M. Schirra’s Sigma 7 mission, NASA extended it to 22 orbits for a flight time of 34 hours, the longest American space mission to that time. The length of the mission required expanded worldwide tracking support and around the clock support from the Mercury Control Center (MCC) at Cape Canaveral, Florida, headed by Flight Directors Christopher C. Kraft and John D. Hodge. The extended mission enabled NASA to install several cameras in the spacecraft, including the first test of a slow-scan television system, for Cooper to document his flight. During a press conference on Feb. 8, 1963, he described his mission as “practically a flying camera.” Like the other Mercury astronauts before him, Cooper named his spacecraft, choosing Faith 7 to represent his faith in the technology and the personnel to enable the longest American spaceflight ever attempted and the “7”to signify the seven Mercury astronauts.

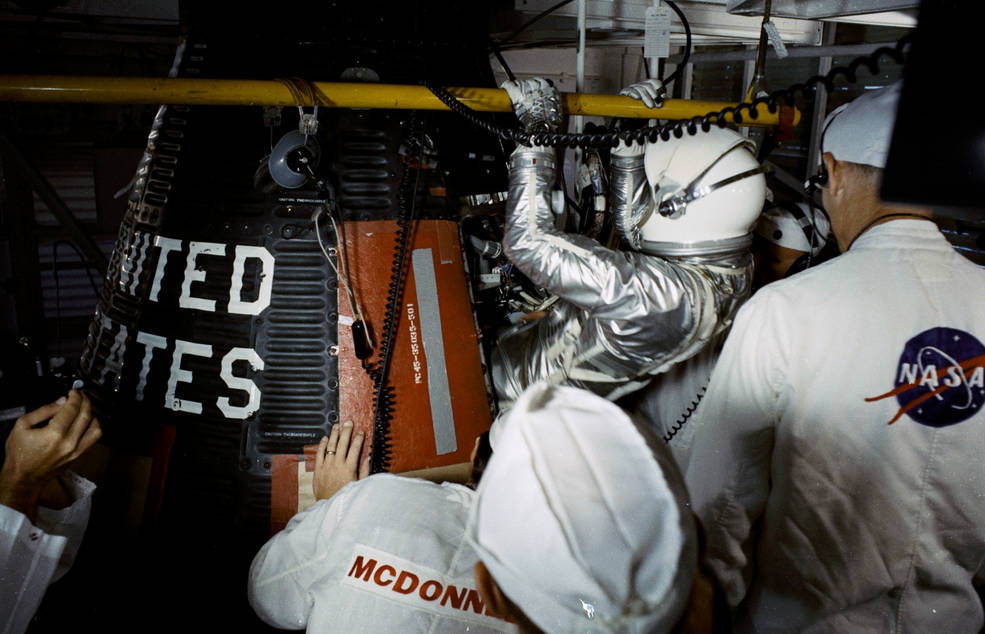

Left: An artist paints the Faith 7 logo onto L. Gordon Cooper’s Mercury spacecraft. Middle: Technicians assist Cooper into his Faith 7 capsule. Right: Liftoff of Faith 7 on its Atlas booster.

Originally planned for a mid-April 1963 launch, problems certifying the Atlas booster resulted in the flight slipping to mid-May. The first launch attempt on May 14, with Cooper strapped in his capsule for six hours, had to be scrubbed due to spacecraft and ground tracking problems. On May 15, Cooper once again suited up, took the transfer van to Launch Pad 14, and strapped inside the tiny capsule. A few minor technical issues briefly held up the countdown, but at 8:04 a.m. EDT, the engines of the Atlas rocket ignited, and Cooper took off to become the sixth American in space.

Three of astronaut L. Gordon Cooper’s Earth observation photographs. Left: The Ganges River delta. Middle: The snow-capped Himalayan mountain range. Right: The vast Pacific Ocean.

The Atlas performed so well that Cooper’s orbit in Faith 7 nearly matched predicted values, prompting capsule communicator (capcom), the astronaut in MCC who talks directly with the astronaut in orbit, Schirra to tell Cooper that he was “smack-dab in the middle of the plot.” Cooper’s first day in orbit went exceedingly smoothly, and he proceeded through his assigned tasks, such as photography of the Earth, collection of urine samples for later analysis by scientists, and monitoring his spacecraft’s condition. He took time out to sample some of the specially-packaged foods. Among his 11 experiments, Cooper deployed one of the technology studies, a 6-inch sphere equipped with strobe lights to determine how well he could track it in space. Although the sphere deployed as planned and the strobe lights appeared to work properly, Cooper could only see it under certain lighting conditions. Another experiment to deploy a 30-inch Mylar balloon covered with fluorescent paint and attached to the capsule with a 100-foot tether, did not succeed. At 9 hours 13 minutes into the flight, he exceeded Schirra’s time in space on Mercury 8, becoming the most-traveled American astronaut. Cooper attempted to sleep, but the Earth passing by kept him more interested in staying awake and conducting observations. Other than the distractions, Cooper reported sleeping better in weightlessness than on the ground.

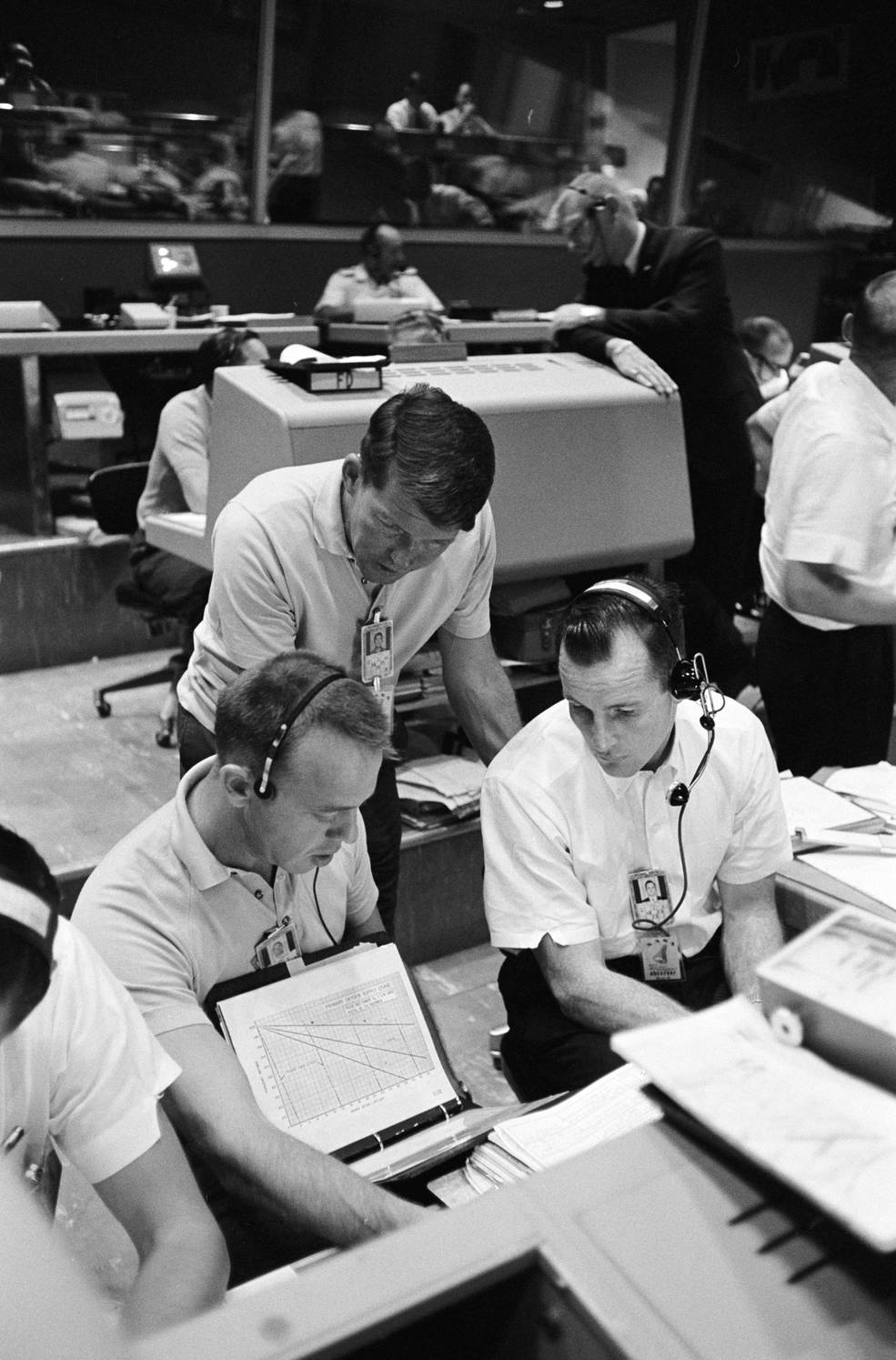

Left: A still image from the slow-scan TV broadcast. Middle: In the Mercury Control Center (MCC), Flight Director Christopher C. Kraft, center, has just given the go for the full 22-orbit mission. Right: In the MCC, NASA astronaut capsule communicators Alan B. Shepard, left, Walter M. Schirra, and Edward H. White.

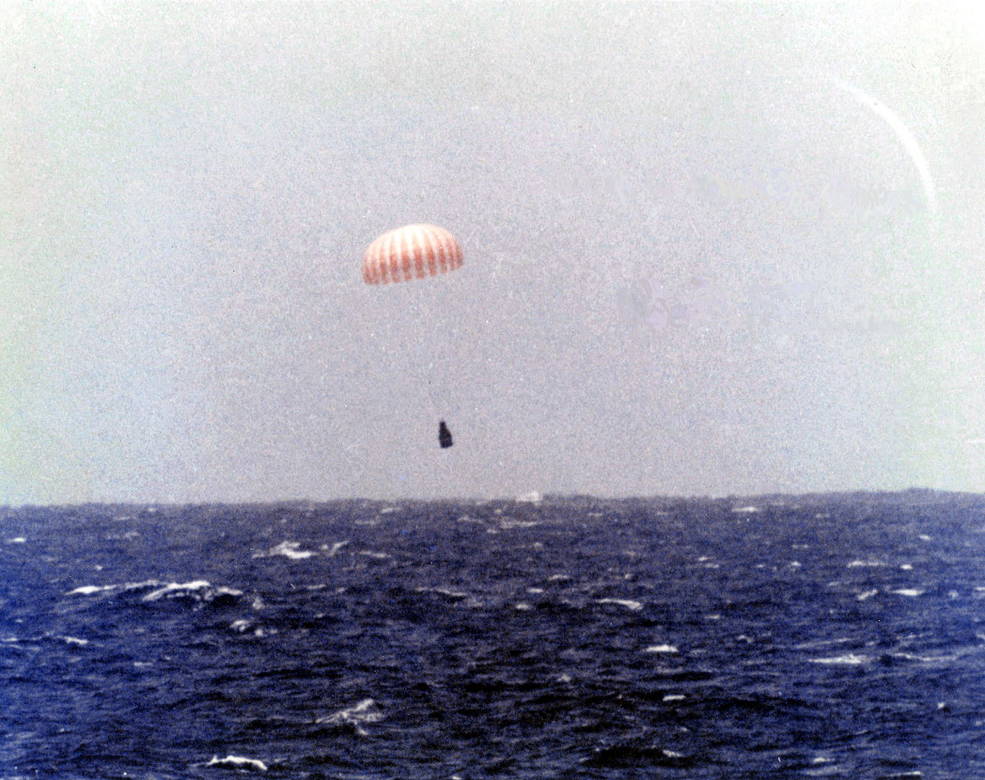

During his 17th orbit, Cooper transmitted slow-scan black and white television images back to the MCC, the first TV transmission from an American crewed spacecraft. The images, however, appeared of poor quality, likely due to the low light conditions in the spacecraft. Flight directors in MCC gave Cooper the go to complete the full 22-orbit mission. Faith 7 continued to perform well until the 19th orbit when a faulty signal erroneously indicated that the spacecraft had begun its reentry. Two orbits later, a short circuit knocked out the automatic stabilization and control system. When the carbon dioxide level began to rise in the cabin and in his spacesuit, Cooper reported to MCC in his usual understated manner, “Things are beginning to stack up a little.” He took over manual control of the spacecraft, orienting it for the critical firing of the retrorockets to take him out of orbit. He manually completed the retro-fire burn, and once the capsule competed the fiery reentry, he manually deployed first the drogue parachute at 50,000 feet to stabilize the spacecraft and then the main at 11,000 feet to slow his descent for splashdown. Finally, he deployed the landing bag below the spacecraft just prior to hitting the water. Faith 7, with Cooper inside, landed about 80 miles southeast of Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean, less than five miles from the prime recovery ship U.S.S. Kearsarge (LHD-3).

Left: Aerial view of the prime recovery ship the U.S.S. Kearsarge, with sailors in white uniforms spelling out “Mercury 9” on the deck. Middle: The Faith 7 capsule with astronaut L. Gordon Cooper inside moments before splashdown. Right: As seen from one of the recovery helicopters, Navy divers jump into the water to secure the Faith 7 capsule after splashdown.

Within minutes, helicopters had deployed to the splashdown site and swimmers jumped in the water to secure flotation devices around Faith 7. Cooper elected to remain inside the capsule, so sailors attached a tow line to it. Kearsarge approached, reeled the spacecraft in, and sailors hoisted it onto an elevator deck, 35 minutes after splashdown. Recovery crews blew the spacecraft’s side hatch, and Cooper greeted them with a big smile. They pulled him from the capsule, and despite having spent more time in space than any other American, and feeling a little dizzy upon first standing, Cooper had no difficulty walking from the spacecraft to the ship’s medical clinic for a thorough physical examination by NASA flight surgeons. Below decks, Cooper received the now-customary and congratulatory telephone call from President Kennedy and also talked with his wife Trudy.

Left: U.S. Navy swimmers place a flotation collar around the Faith 7 capsule, with astronaut L. Gordon Cooper inside, shortly after splashdown. Middle: Recovery workers prepare to remove the hatch from the Faith 7 capsule on the elevator deck of the U.S.S. Kearsarge. Right: A smiling Cooper awaits removal from his spacecraft at the conclusion of his successful Mercury-Atlas 9 mission.

As Kearsarge steamed for Honolulu, Cooper continued his readaptation to Earth’s gravity, his main complaint being dehydration. Further medical tests showed him to be in good health. On May 18, Cooper helicoptered from the ship to Hickam Air Force Base (AFB) in Honolulu, where he met his wife Trudy and their two daughters, as well as Hawaii Governor John A. Burns and Admiral Harry D. Felt, commander of the Pacific Fleet. After more ceremonies, Cooper and his family boarded a jet to fly them non-stop to Patrick AFB, near Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Left: Aboard the U.S.S. Kearsarge, astronaut L. Gordon Cooper, left, eats cake with Capt. Eugene P. Rankin to celebrate his successful Mercury-Atlas 9 mission. Middle: Cooper greets Admiral Harry D. Felt at Hickam Air Force Base (AFB) in Honolulu, as his wife Trudy and two daughters look on. Right: Cooper and his wife Trudy, accompanied by their two daughters, arrive at Patrick AFB in Florida.

After arriving at Patrick AFB, they boarded convertible limousines for the drive up to Cape Canaveral, the route lined with approximately 80,000 well-wishers. Cooper gave a brief press conference to an assembled 700 journalists, describing his record-setting flight. The Coopers had a chance to rest the next day before jetting to Washington, D.C., on May 21. A limousine drove them from Andrews AFB to the White House, where President Kennedy presented Cooper with a Distinguished Service Medal. Then it was down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol, where Cooper addressed a Joint Session of Congress.

Left: Astronaut L. Gordon Cooper, accompanied by his wife Trudy and NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, ride in the motorcade from Patrick Air Force Base to Cape Canaveral, Florida. Middle: Cooper, at right, receives the Distinguished Service Medal from President John F. Kennedy at the White House in Washington, D.C. Right: Cooper speaks to a Joint Session of Congress about his mission.

Festivities continued the next day in New York City with a ticker tape parade estimated to have drawn four-and-a-half million people. On May 23, the Coopers flew to Houston, home of the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center, by then the home of the astronauts and the future home of Mission Control. They took part in another parade and a reception at the Sam Houston Coliseum. They welcomed the next day as a day of rest, before Cooper returned to work on May 27 to begin his postflight debriefings with managers and engineers. On June 28, Cooper and his wife flew their private plane to Shawnee, Oklahoma, Cooper’s hometown, for a welcome home celebration.

Left: Astronaut L. Gordon Cooper, accompanied by his wife Trudy, addresses a crowd assembled to welcome him to Houston International Airport. Middle: The Coopers in the motorcade in downtown Houston. Right: Cooper in a motorcade in his hometown of Shawnee, Oklahoma. Credit: Image courtesy The Oklahoman.

Project Mercury gave NASA the confidence to move on to Project Gemini during which 10 two-person crews mastered the critical techniques required to achieve a lunar landing before the end of the decade. NASA had briefly considered flying a Mercury-Atlas 10 mission lasting up to eight days, with Shepard as the pilot, but in the end decided that Project Gemini should take priority. Cooper contributed to that effort when he flew another record-setting mission, the eight-day Gemini V flight with Charles “Pete” Conrad, in August 1965, and served as the backup commander for Apollo 10 in 1969, before retiring from NASA in July 1970.

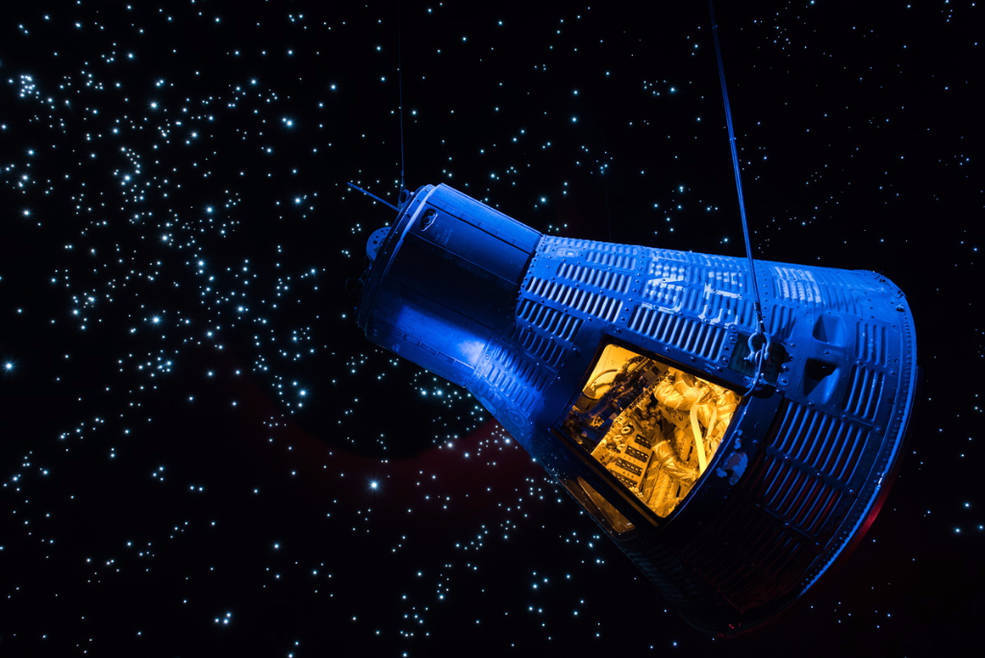

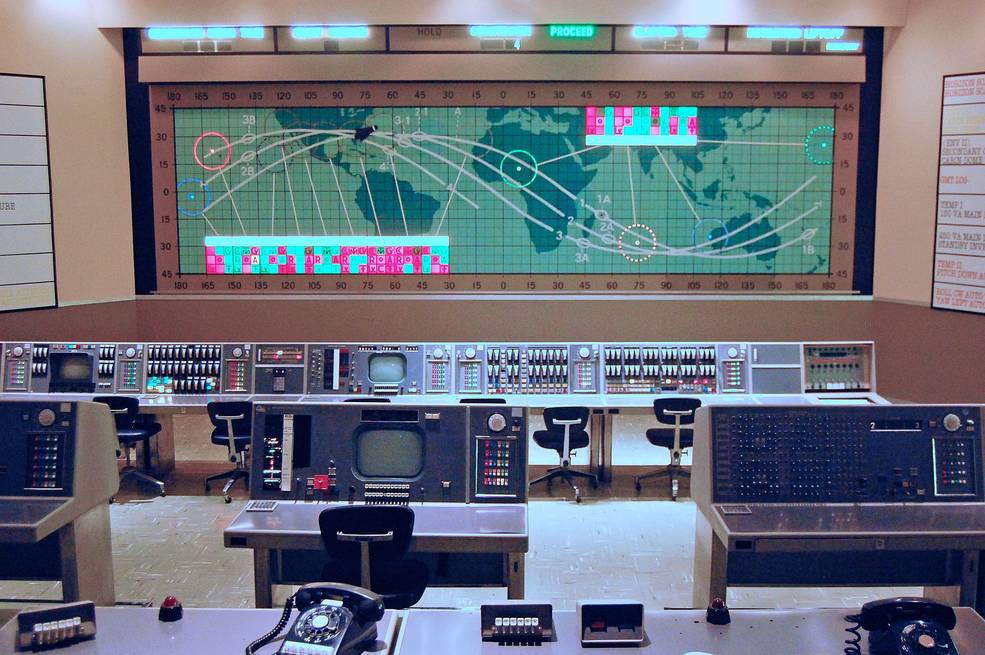

Left: The Faith 7 capsule in Denver during its 1964 tour of the United States.Credit: Image courtesy Denver Post. Middle: The Faith 7 spacecraft on display at Space Center Houston. Credit: Image courtesy Space Center Houston. Right: Reconstruction of Mercury Control Center at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Visitors Center. Credit: Image courtesy KSC Visitors Center.

Following splashdown and postflight inspections, the Faith 7 capsule embarked on a 50-state-capital tour, beginning in Oklahoma City on Sept. 21, 1963, and ending in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 1, 1964. After a brief time on display in Santiago, Chile, it returned to Houston where it joined other exhibits in MSC’s visitor center. Faith 7 is currently on display at Space Center Houston. A recreation of the MCC is on display inside the Kurt Debus Center at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex.