The primary goals of Project Gemini included proving the techniques required for the Apollo Program to fulfill President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth before the end of the 1960s. Paramount among those techniques was rendezvous and docking necessary to implement the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous method NASA chose for the Moon landing missions. Additional goals of Gemini included proving that astronauts could work outside their spacecraft during spacewalks and ensuring that spacecraft, and astronauts could function for at least eight days, considered the minimum time for a roundtrip mission to the Moon. In March 1965, Gemini 3 completed the first crewed test flight of the new spacecraft, and conducted the first orbital maneuvers. Gemini IV in June demonstrated the feasibility of spacewalking, and Gemini V in August remained in space for eight days. The next two missions planned to demonstrate rendezvous and docking and complete a 14-day stay in space, respectively.

Left: Gemini VI astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, left, and Walter M. “Wally” Schirra.

Right: The original Gemini VI crew patch, showing a Gemini spacecraft making a

rendezvous with an Agena target; the GTA stands for Gemini Titan Agena.

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation built the Gemini spacecraft at its St. Louis plant while the Martin-Marietta Corporation assembled the Titan-II rocket in Baltimore. For the Gemini VI mission, NASA named Mercury veteran Walter M. “Wally” Schirra the command pilot and space rookie Thomas P. Stafford the pilot. Mercury and Gemini veteran Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom served as the backup command pilot and Gemini 3 veteran John W. Young as the backup pilot.

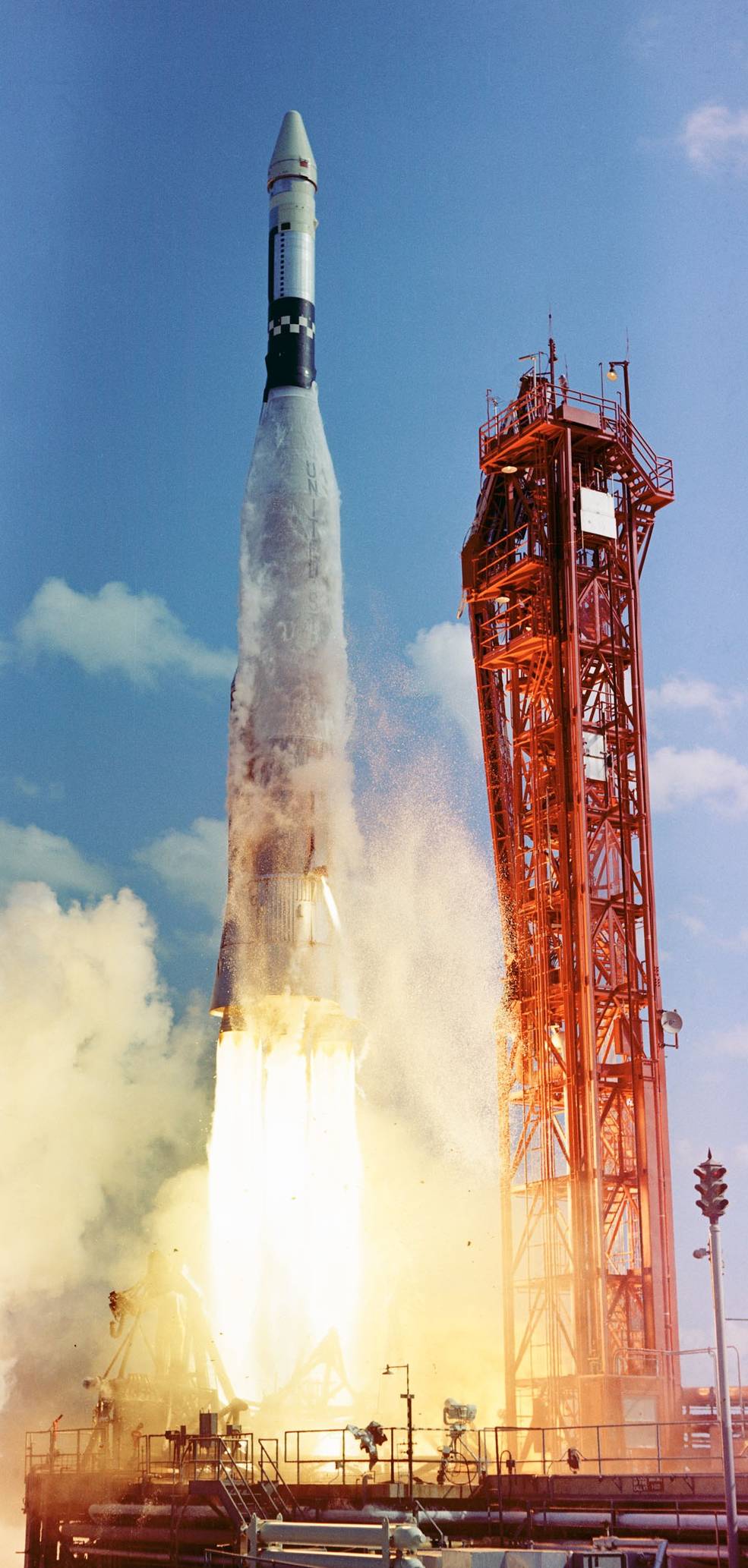

Left: NASA astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, left, and Walter M. “Wally” Schirra climb aboard their Gemini VI spacecraft for the Oct. 25, 1965, launch attempt. Middle: The launch of the Gemini VI Agena target vehicle that failed six minutes into the flight. Right: The redesigned Gemini VI patch, representing the change to a rendezvous with another Gemini spacecraft.

The original Gemini VI mission plan involved completing a rendezvous and docking with an Agena target vehicle launched 101 minutes before their own liftoff. On Oct. 25, 1965, an Atlas-Agena rocket blasted off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station’s Pad 14, just a few miles from Pad 19 where Schirra and Stafford sat inside their Gemini capsule atop its Titan booster. However, within six minutes, it was clear that something had gone wrong. In fact, the Agena’s engine had exploded, and the vehicle did not reach orbit. Schirra and Stafford had no target to chase and climbed out of their spacecraft. NASA management decided to proceed with the next mission, the 14-day Gemini VII in early December, and use it as a rendezvous target for Gemini VI. Workers replaced the Gemini VI Titan rocket on Pad 19 with the rocket for Gemini VII, stacking that rocket on Oct. 29. Engineers developed procedures to ensure that a second rocket could be stacked on the pad within a few days following the launch of the first, allowing the rendezvous to take place within the 14 days that Gemini VII would be in orbit.

Left: Gemini VII astronauts James A. Lovell, left, and Frank Borman.

Right: The Gemini VII crew patch.

On July 1, 1965, NASA selected Frank Borman as the command pilot and James A. Lovell as the pilot for the 14-day Gemini VII endurance flight. Although both were making their first spaceflight, they had served as the backup crew for Gemini IV. Gemini IV veteran and first American spacewalker Edward H. White and rookie Michael Collins served as the backup crew. To aid in their comfort during the lengthy flight, Borman and Lovell wore lightweight suits that they could easily remove, roll up, and stow under their seats. The suits had no hard helmet or neck ring, with the visor held in place with a zipper. The cramped spacecraft created a challenge for stowage of all the necessary equipment for a two-week mission, including the required food, and then for the garbage the crew generated. Unlike previous crews in which one astronaut always kept watch, Borman and Lovell’s coordinated their sleep-work cycles. During the flight, Borman and Lovell conducted 20 experiments, eight of them medical to evaluate their responses to long-duration weightlessness, more than any previous flight.

Left: The 14-day food supply for the Gemini VII mission. Middle: Gemini VII astronauts

James A. Lovell, left, and Frank Borman, wearing their lightweight spacesuits, exit the

suit-up trailer on their way to Launch Pad 19. Right: The launch of Gemini VII from

Launch Pad 19.

Following a nearly flawless countdown, Gemini VII took to the skies on Dec. 4, 1965. Shortly after reaching orbit, they turned their spacecraft around and attempted to station-keep with their Titan rocket’s spent second stage, a task made difficult by its venting of excess fuel. That activity completed, Borman and Lovell began their experiment program and settled in for their 2-week stay in space. Two days into the flight, Lovell took off his suit, greatly increasing his comfort level, while Borman remained warm and uncomfortable in his suit. It took another two days for mission managers to relent and allow him to remove his suit as well, following which he felt much more comfortable. The pair continued their suite of experiments and took photographs of the Earth, awaiting the arrival of Gemini VI.

Left: Gemini VII view of the Titan second stage during station-keeping.

Right: NASA astronaut Frank Borman aboard Gemini VII, photographed by James A. Lovell.

Launch Pad 19 suffered minimal damage from the Gemini VII liftoff and workers erected Gemini VI’s Titan rocket the next day. On Dec. 12, Gemini VII’s ninth day in space, Schirra and Stafford strapped into their spacecraft for a second launch attempt. The countdown clock ticked down to zero, and the Titan’s first stage engines ignited. And shut off after just 1.2 seconds, resulting in the first on-the-pad abort of the U.S. space program. Although the mission clock aboard the spacecraft had started, the rocket had not lifted off, and Schirra made the split-second decision not to eject himself and Stafford from the spacecraft. Engineers traced the cause of the abort to a dust cap inadvertently left in the engine compartment. After workers took care of that issue, Schirra and Stafford tried to launch again on Dec. 15, and the third time proved to be the charm. When they reached orbit, for the first time in history, four people were in space simultaneously.

Left: The Dec. 12, 1965, Gemini VI launch abort. Middle: NASA astronauts Walter M. “Wally” Schirra, left, and Thomas P. Stafford climb aboard their Gemini VI spacecraft for their third launch attempt. Right: Gemini VI finally takes to the skies on Dec. 15, 1965.

Over the next six hours, Schirra and Stafford aboard Gemini VI conducted a series of orbital maneuvers to catch up with Borman and Lovell awaiting them aboard Gemini VII. At a distance of 270 miles, Gemini VI’s rendezvous radar established a solid lock on Gemini VII. Once the distance between the two spacecraft had closed to 60 miles, Schirra could see Gemini VII, exclaiming, “My gosh, there is a real bright star out there!” At a distance of 3,000 feet, Schirra began braking his spacecraft to slow the approach. He halted the approach at a distance of 130 feet, with no relative velocity between the two spacecraft, accomplishing the world’s first space rendezvous. Flight controllers in the Mission Control Center at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, erupted in cheers while managers lit celebratory cigars. For the next three orbits around the Earth, the two spacecraft stayed at ranges of 300 feet to as close as one foot from each other, with Gemini VI doing most of the maneuvering for station-keeping, fly-arounds, formation flying, and parking the spacecraft in specific relative positions. As the astronauts’ sleep period approached, Schirra backed away to a safe overnight position about 10 miles away.

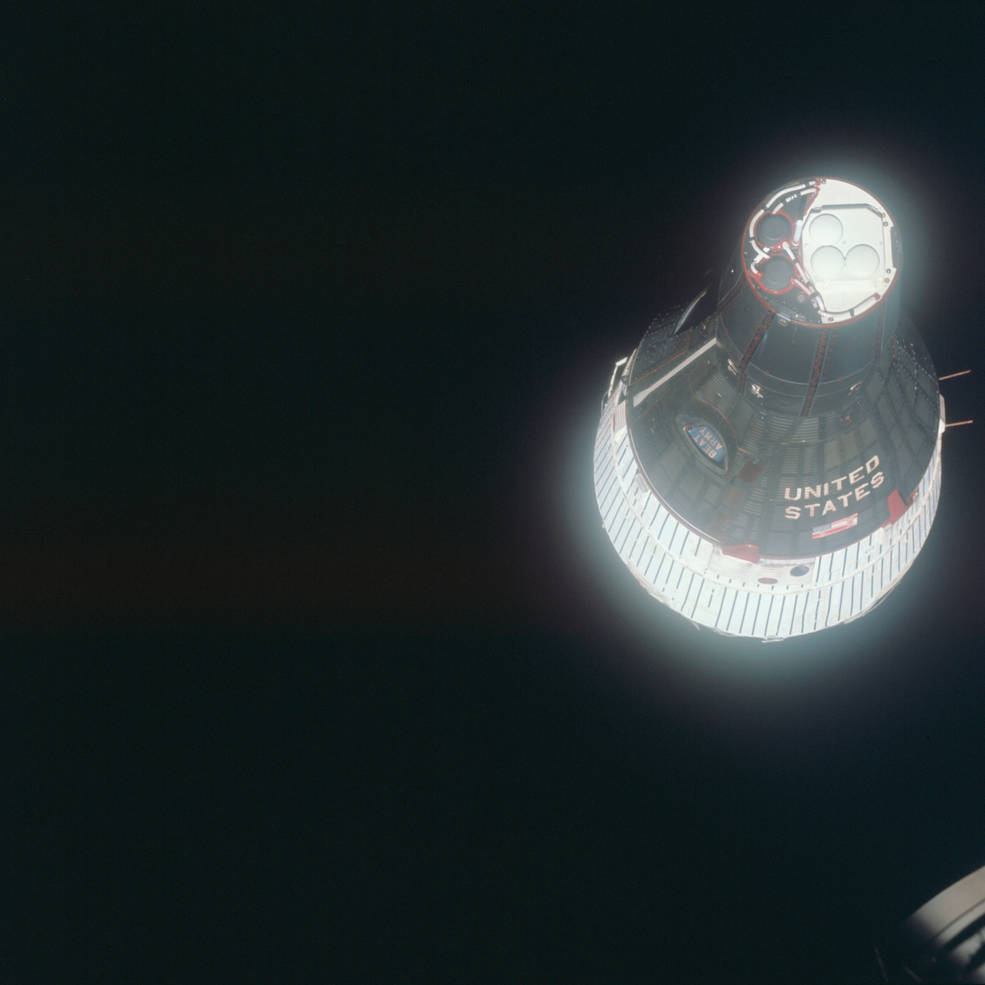

Left: View from inside Gemini VII of the approaching Gemini VI spacecraft. Middle: View from inside Gemini VI of the Gemini VII spacecraft during the rendezvous maneuvers. Right: Another view of Gemini VII from Gemini VI.

Early the next morning, the following exchange took place among the two spacecraft and astronaut Elliott M. See as the capsule communicator (Capcom) in Mission Control in Houston:

Gemini VI: We have an object. It looks like a satellite going from north to south, up in a polar orbit. He’s in a very low trajectory, traveling from north to south. It has a very high [fineness] ratio. It looks like it might be [inaudible]. It’s very low; it looks like he might be going to re-enter soon. Stand by, One. It looks like he’s trying to signal us. [Stafford and Schirra play “Jingle Bells”].

Gemini VII: We got him, too! [Laughter].

Gemini VI: That was live, Seven, not taped.

Houston (See): You’re too much, Six.

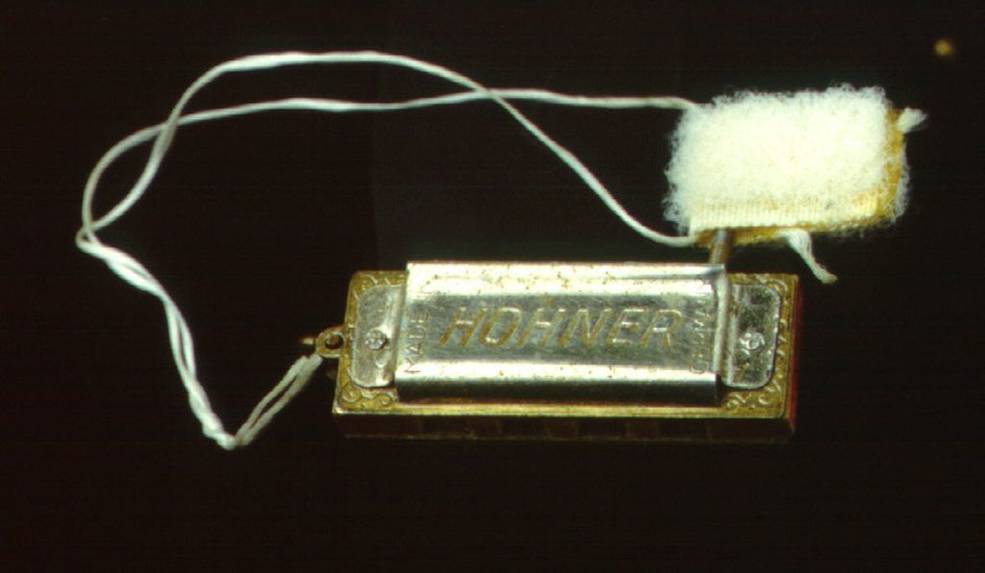

If you listen to the audio of the conversation, you can hear the sounds of an 8-note Hohner “Little Lady” harmonica and a handful of small bells, the first musical instruments played in outer space. Both are on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

The first musical instruments played in space during the Gemini VI mission – a Hohner

harmonica, left, and a set of bells.

Credits: National Air and Space Museum.

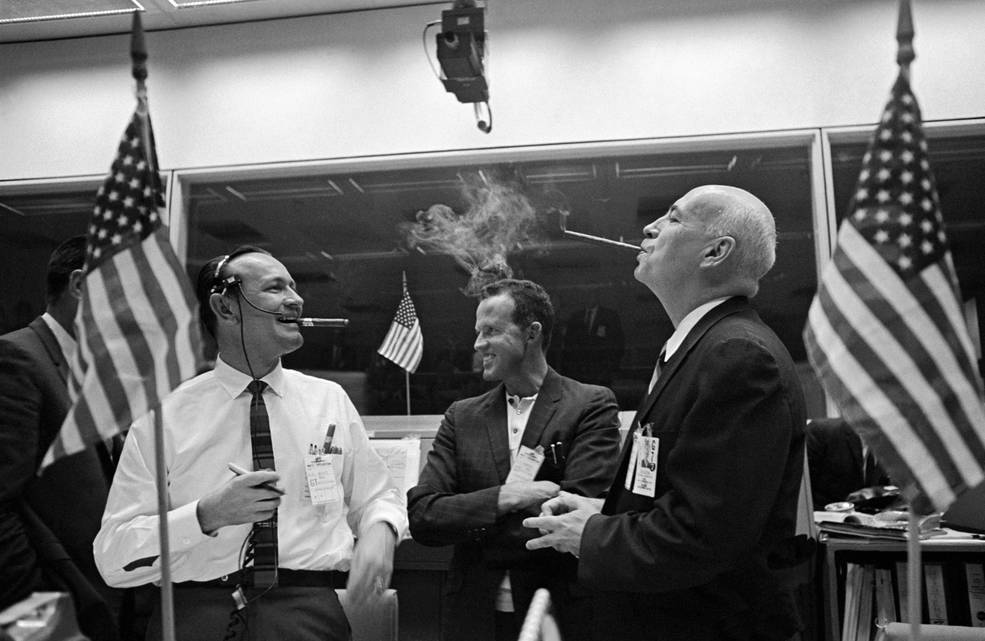

Left: Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson

Space Center in Houston, during the marathon Gemini VII mission. Right: Gemini

VII Flight Director Christopher C. Kraft,left, celebrates the successful Gemini VI and

VII rendezvous with astronaut L. Gordon Cooper and MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth.

With the rendezvous successfully completed, it was time for Gemini VI to come home. Schirra called to Gemini VII, “Really good job, Frank and Jim. We’ll see you on the beach.” He jettisoned the spacecraft’s equipment section and fired the retrorockets to drop them from orbit. After a nominal entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, the spacecraft deployed first its drogue parachute at 45,000 feet in altitude and then its main parachute at 10,000 feet. Gemini VI splashed down eight miles from its target point in the western Atlantic Ocean southeast of Cape Canaveral, Florida, and within view of the prime recovery ship, the USS Wasp (CVS-18). Gemini VI had completed 16 revolutions around the Earth in a flight lasting 25 hours and 16 minutes. Schirra elected to remain inside the capsule as recovery team members lifted it out of the water and onto the carrier’s deck, where a throng of cheering sailors greeted them. By the next day, Schirra and Stafford had returned to crew quarters at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC).

Left: The prime recovery ship USS Wasp (CVS-18) ready to welcome home the

Gemini VI astronauts. Right: Photograph taken from a helicopter of the Gemini VI

recovery operations, with the USS Wasp in the background.

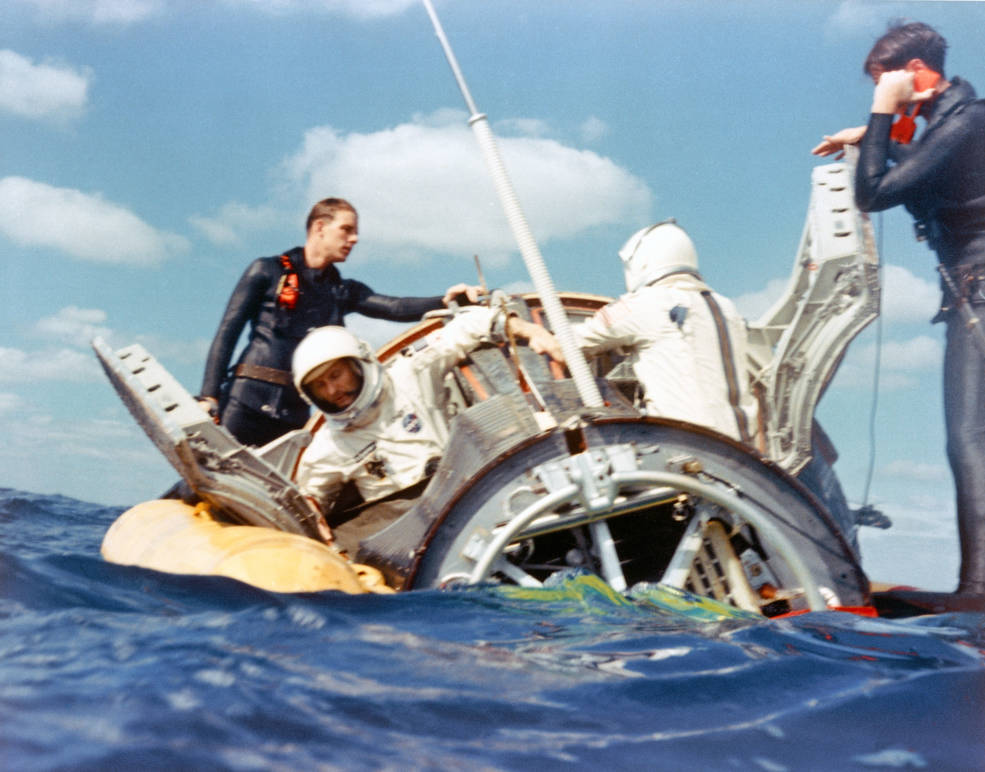

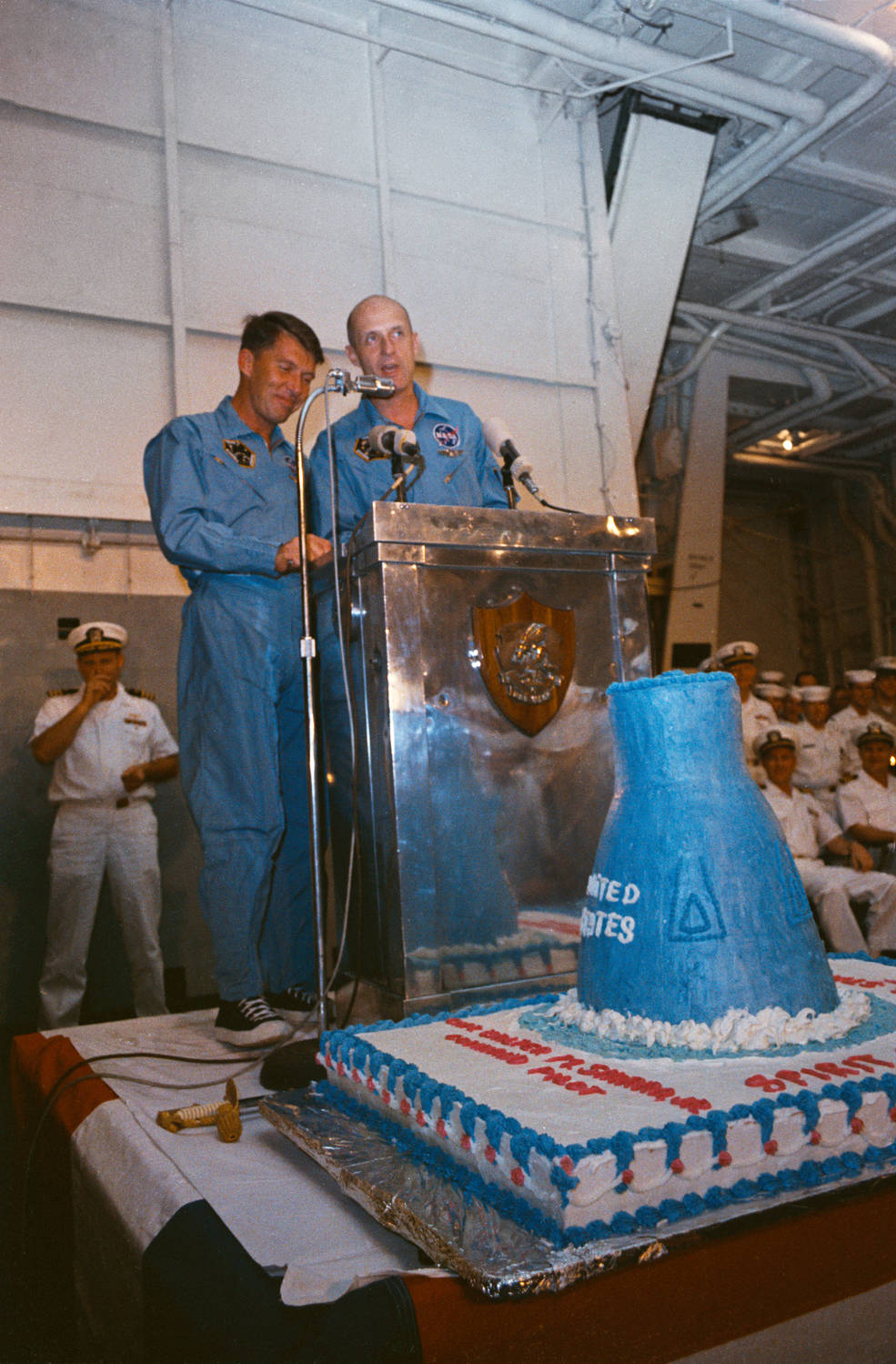

Left: Photograph taken by one of the recovery swimmers shortly after the Gemini VI splashdown, with astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, left, and Walter M. “Wally” Schirra emerging from the spacecraft. Middle: Astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, left, and Walter M. “Wally” Schirra shake hands in front of their Gemini VI spacecraft aboard the prime recovery ship USS Wasp. Right: Gemini VI astronauts speak to the crew of the USS Wasp shortly after their recovery, with a celebratory cake in front of them.

In orbit, Gemini VII astronauts Borman and Lovell still had three more days to go before their own homecoming. They continued with their experiment program and dealt with minor issues with some of the spacecraft’s thrusters and an errant fuel cell. On their last day in space, they packed up and tidied up the capsule that had been home for two weeks, often described as having as much room as the front seat of a Volkswagen Beetle.

Left: Astronaut Frank Borman conducting a visual acuity test while taking his temperature during the 14-day Gemini VII mission. Middle: Gemini VII view of the Nile Delta in Egypt. Right: Gemini VII view of the Dominican Republic.

On Dec. 18, Borman jettisoned the spacecraft’s instrument section and fired its retrorockets. Reentry and parachute deployments took place as expected with no issues, and Gemini VII splashed down southeast of Cape Canaveral, about seven miles from the target point. They had orbited the Earth 206 times and spent a record-setting 13 days, 18 hours, and 35 minutes in space, a mark that stood for more than 4 years. Helicopters from the USS Wasp, performing its second crew recovery in two days, retrieved Lovell and Borman from the sea and delivered them to the deck of the carrier. A little shaky after two weeks in weightlessness, they were otherwise in good health although both had lost weight.

Left: The prime recovery ship USS Wasp ready to welcome home the Gemini VII astronauts. Right: Photograph taken from a recovery helicopter of the Gemini VII spacecraft descending on its parachutemoments before splashdown.

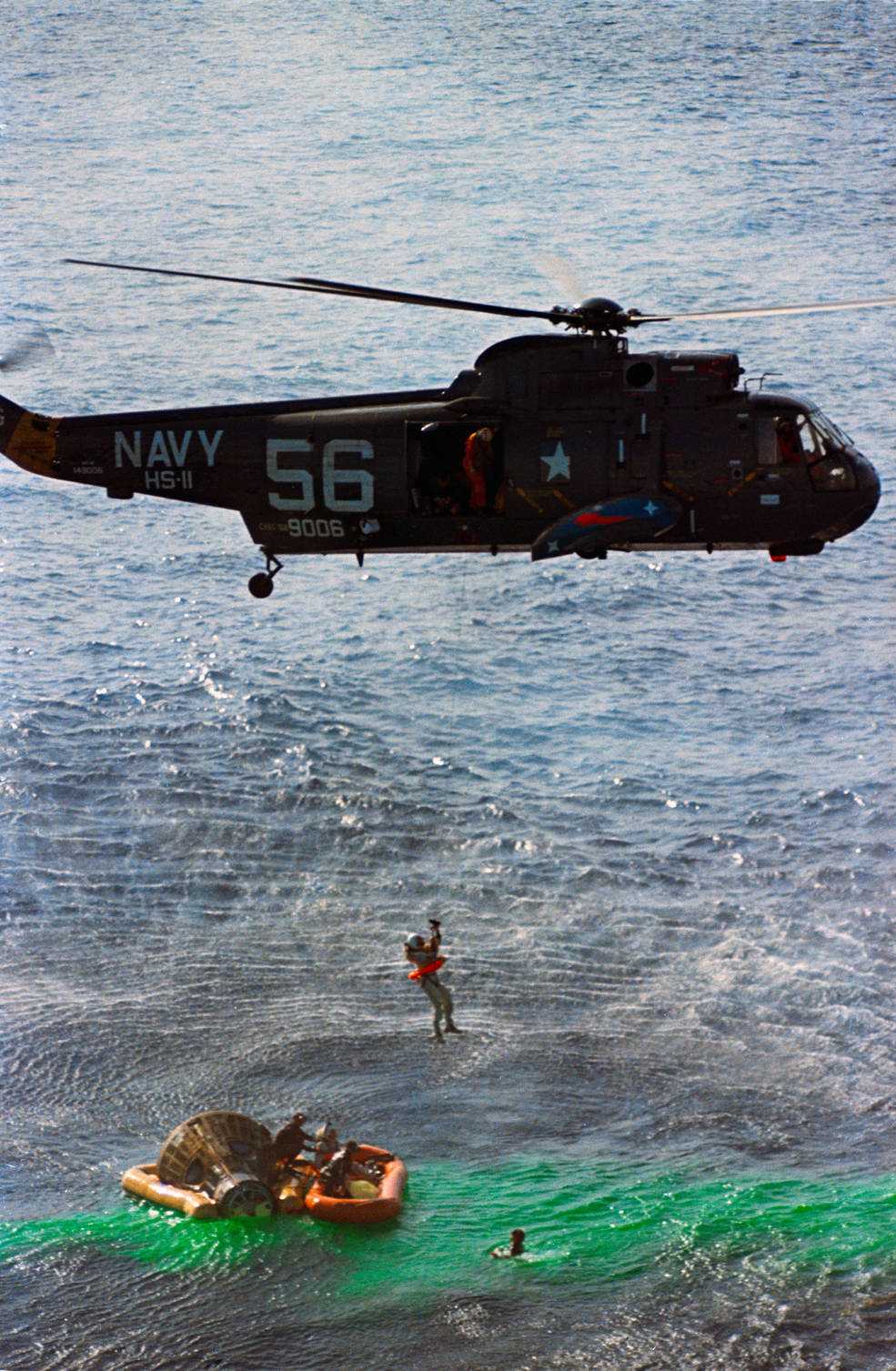

Left: Gemini VII astronauts James A. Lovell, left, and Frank Borman sit in the life raft awaiting hoisting aboard the recovery helicopter. Middle: Recovery crews hoist Lovell from the raft into the helicopter. Right: Recovery crew lift Borman into the helicopter.

Left: NASA astronauts James A. Lovell, left, and Frank Borman aboard the prime recovery ship USS Wasp after their record-setting 14-day Gemini VII mission. Right: Gemini VII astronauts Lovell, left, and Borman slicing their celebratory cake aboard USS Wasp.

Sailors retrieved the capsule from the sea, and two days later, offloaded both spacecraft at Mayport Naval Station near Jacksonville, Florida. Borman and Lovell reunited with Schirra and Stafford at KSC’s crew quarters the day after splashdown. After a few days of post-mission debriefings, the crews returned to Houston and gave an overview of their historic mission to reporters at MSC on Dec. 30.

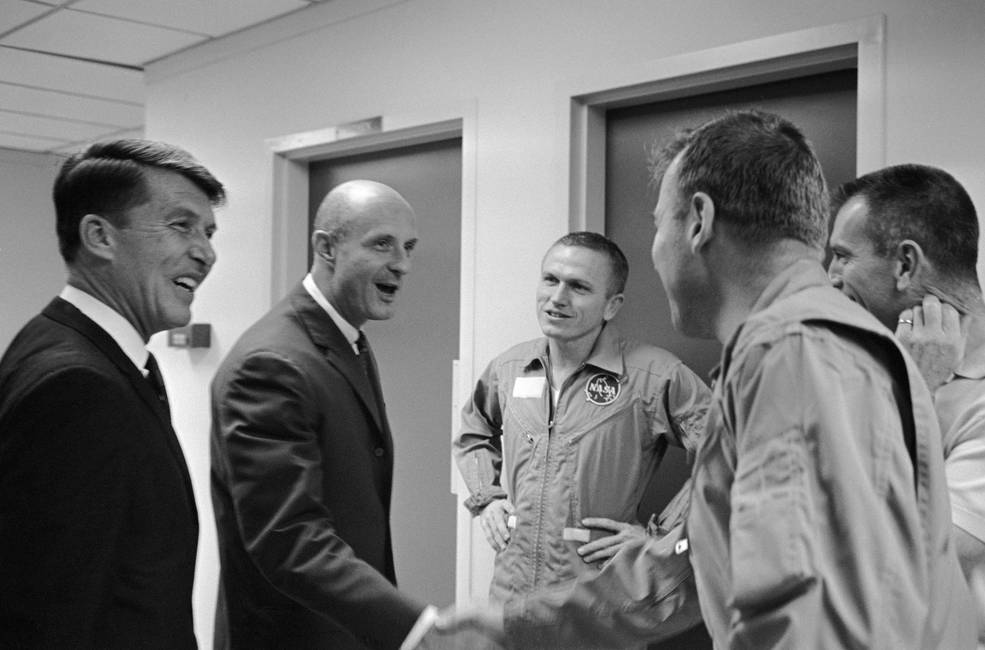

Left: Reunion of Gemini VI and VII astronauts Walter M. “Wally” Schirra, left, Thomas P. Stafford, Frank Borman, and James A. Lovell at crew quarters at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Middle: Gemini VII and VI spacecraft sit on dock at Mayport Naval Station near Jacksonville, Florida, after offloading from the prime recovery ship USS Wasp. Right: Gemini VI and VII astronauts hold their postflight press conference, along with NASA Administrator James E. Webb and Manned Spacecraft Center Deputy

Director George M. Low.

On Feb. 15, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced that he was sending Schirra and Borman on a three-week, eight-country goodwill tour to promote the scientific, technological, and educational values of the U.S. space program. Accompanied by their wives Jo Schirra and Susan Borman, they departed on Feb. 21 aboard a presidential jet. Their itinerary took them to Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand. As they were leaving Taipei, Taiwan, on March 1, they learned of the deaths the previous day of Elliot M. See and Charles A. Bassett, the prime crew for the upcoming Gemini IX mission, in an airplane crash in St. Louis. Upon their arrival in Hawaii on March 16, they learned of the aborted Gemini VIII mission. Schirra traveled to Okinawa, Japan, to escort fellow astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and David R. Scott back to the U.S. after their harrowing spaceflight, first landing at Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu before returning to KSC.

Left: Astronauts Walter M. “Wally” Schirra, left, and Frank Borman wave to crowds in Taipei, Taiwan, during their post-mission goodwill tour. Middle: Borman, left, and Schirra in Manilla. Right: Australian Prime Minister Harold E. Holt, center, hosts Jo and Wally Schirra, left, and Frank and Susan Borman at his home in Melbourne, Australia.

Left: Gemini VI astronaut Walter M. “Wally” Schirra, at center, awaits Gemini VIII astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and David R. Scott at port in Okinawa, Japan. Middle: Schirra, in suit, escorts Armstrong, left, and Scott off the recovery ship USS Leonard F. Mason in Okinawa. Right: Schirra, left, escorts Armstrong and Scott at Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu.

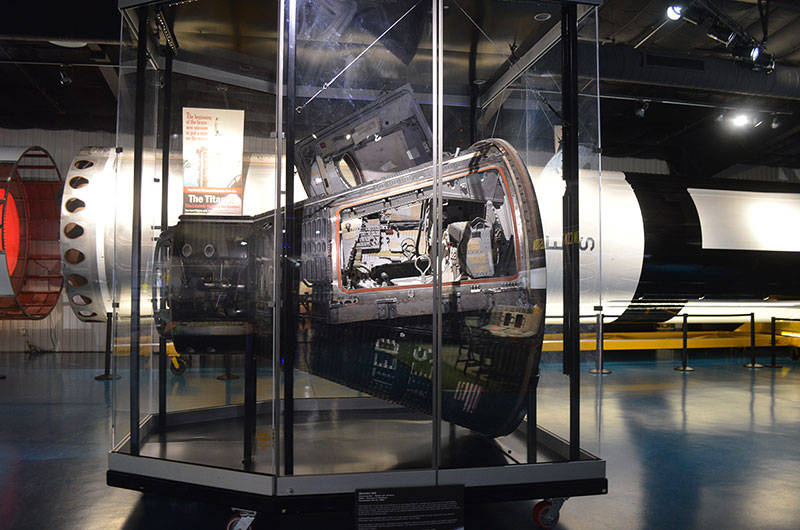

The Gemini VI and VII spacecraft can be viewed at the Stafford Air and Space Museum in Weatherford, Oklahoma, and the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, respectively.

Left: Gemini VI capsule on display at the Stafford Air and Space Museum in Weatherford, Oklahoma, with a model of a Titan rocket in the background. Right: Gemini VII capsule on display at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

Credits: Stafford Air and Space Museum, National Air and Space Museum.

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center