On Nov. 9, 1967, with the Space Age barely 10 years old, NASA took one giant leap forward: the first flight of the Saturn V Moon rocket. For the mission known as Apollo 4, the 363-foot tall Saturn V had rolled out to Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida on Aug. 26, 1967. There it underwent several months of testing including a Countdown Demonstration Test (CDDT), concluded on October 14, leading to many lessons learned that resulted in a fairly trouble-free countdown for the actual launch. NASA planned Apollo 4 as an all-up test flight, meaning testing all three stages of the rocket at one time, and also flying an uncrewed Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM).

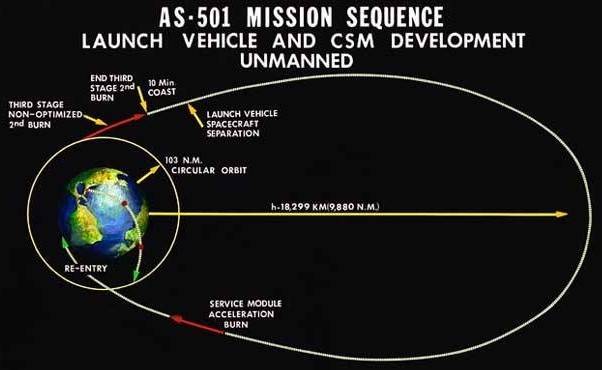

Left: Overall view of the Apollo 4 mission sequence.

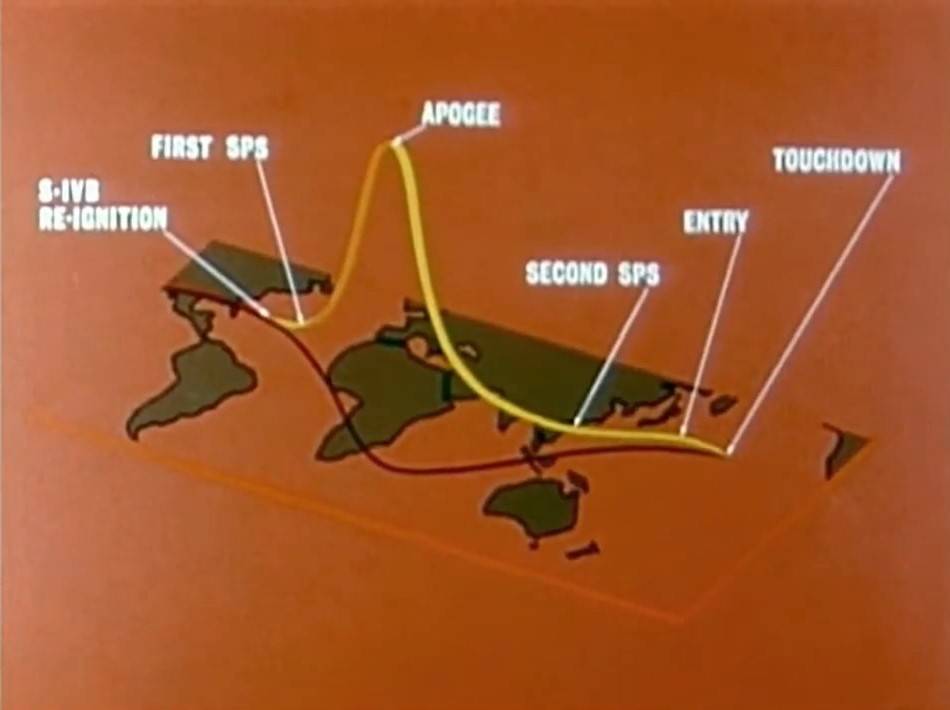

Right: The Apollo 4 flight path superimposed on a world map.

Unlike NASA’s earlier practice of test flying each stage of a new rocket before launching a complete stack, managers used the “all-up” approach for the Saturn V. This method involved testing all three stages for the first time on a single launch, including the restart capability of the rocket’s third stage, needed on later mission to send astronauts toward the Moon. In addition, they decided to test the Apollo CSM, especially the spacecraft’s main engine, needed to enter and leave lunar orbit, and the Command Module’s heat shield, critical for reentering the Earth atmosphere at 25,000 miles per hour. Although Apollo 4 did not include a Lunar Module (LM), the LM Test Article-10R (LTA-10R) flew inside the Spacecraft LM Adapter to gather loads and dynamics data during the powered flight. The LTA-10R remained attached to the rocket’s third stage and burned up on reentry along with the empty stage.

Left: The Apollo 4 Saturn V rocket on Launch Pad 39A shortly after its rollout.

Right: The Mobile Service Structure approaches the Saturn rocket.

After arriving at Launch Pad 39A on Aug. 26, 1967, engineers put the Apollo 4 Saturn V stack through several months of integrated tests. On Sept. 29, they began the CDDT, a planned six-day rehearsal of the final countdown leading to launch. Due to numerous unexpected problems, which the team dealt with successfully, the CDDT did not end until Oct. 14. One of the major problems encountered involved the malfunction of the power-producing fuel cells in the Service Module, necessitating their replacement. Additional problems pushed the planned launch date from Nov. 7 to Nov. 9, with precount activities beginning on Nov. 4 and the terminal countdown two days later. Controllers in KSC’s Launch Control Center’s Firing Room 1 monitored the three-day countdown.

Left: The Apollo 4 Saturn V rocket on Launch Pad 39A during the Countdown Demonstration Test (CDDT).

Middle: The Launch Control Center (LCC) building in the foreground, with the cavernous Vehicle

Assembly Building in the background. Right: Controllers in Firing Room 1 of

the LCC monitor the Apollo 4 CDDT.

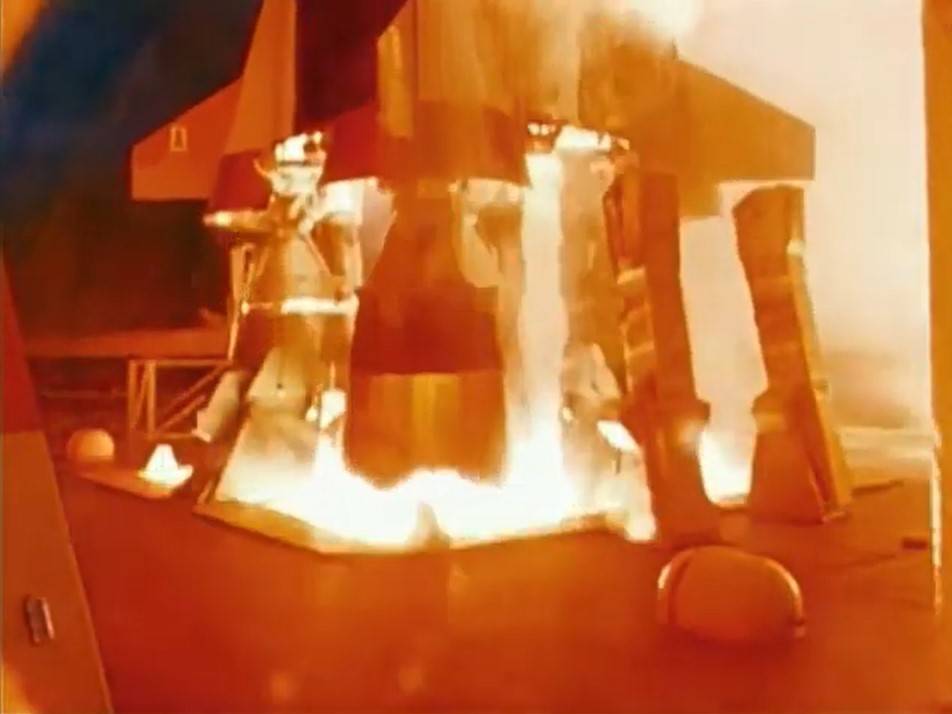

At 7 a.m. on Nov. 9, the Saturn V rocket’s five F-1 first stage engines roared to life, generating 7.5 million pounds of thrust, and a few seconds later the rocket began to climb slowly skyward. Scientists calculated that the noise created by the launch was one of the loudest ever, natural or man-made. The vibrations rattled the press site several miles away. As the rocket cleared the launch tower, control of the flight transferred to Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, where Flight Director Glynn S. Lunney and his team of controllers monitored the flight.

Left: The five F-1 first stage engines provide 7.5 million pounds of thrust as the Apollo 4 Saturn V

rocket begins to lift off from the pad. Middle: Apollo 4 seconds after liftoff.

Right: The Apollo 4 Saturn V during its ascent.

Left: A recoverable film camera aboard the rocket’s second stage records the separation of

the first stage. Right: The recoverable camera records the jettison of the interstage.

Two and a half minutes after liftoff and at an altitude of 40 miles, the first stage exhausted its propellent, shut down its engines, and separated from the ascending rocket. Recoverable film cameras aboard the second stage recorded the event, as well as the separation of the interstage ring 30 seconds later. Meanwhile, the second stage’s five J-2 engines ignited, burning for six minutes to raise Apollo 4’s altitude to 120 miles and its speed to nearly orbital velocity. At that point, the third stage’s single J-2 engine took over, burning for two and a half minutes to place Apollo 4 into a near circular 114-by-116-mile orbit around the Earth.

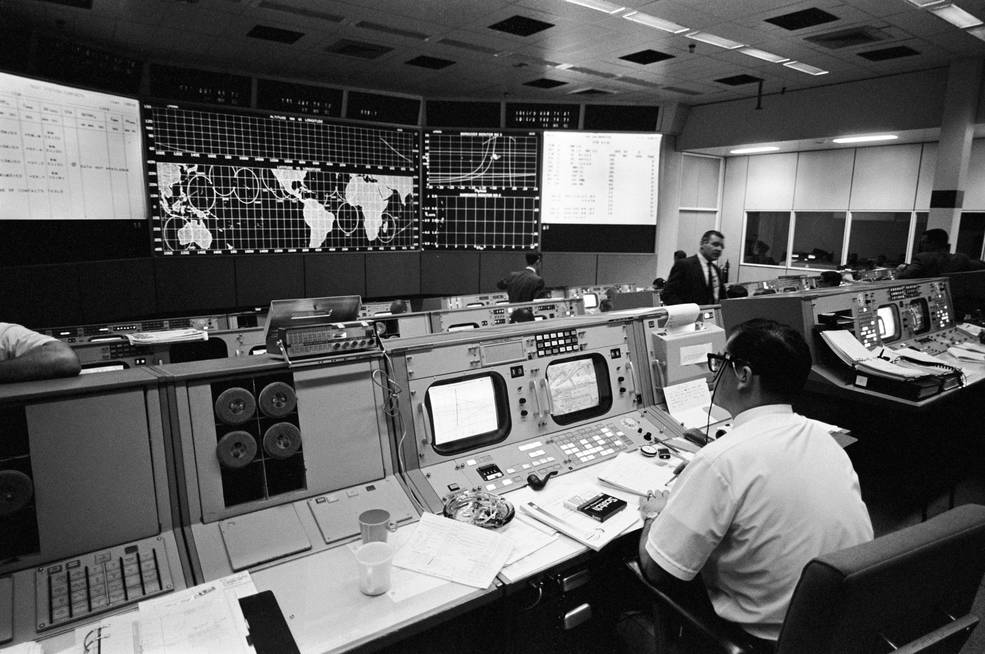

Left: Flight Director Glynn S. Lunney, left, in white shirt, leads his team of controllers in the Mission

Control Center at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston,

as they monitor the ascent of Apollo 4. Middle and right: Flight controllers

monitor the flight of Apollo 4.

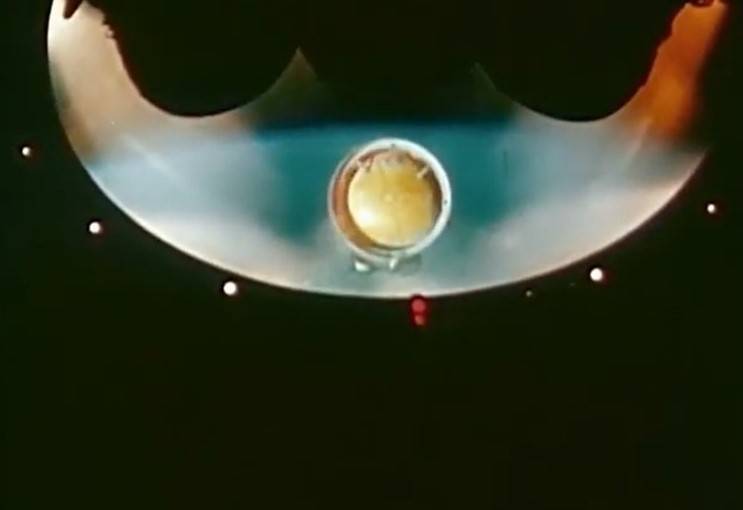

For the next three hours, as Apollo 4 completed two orbits around the Earth, controllers in Mission Control verified the proper functioning of all its systems in preparation for the third stage’s second burn, to send the spacecraft into a highly elliptical Earth orbit. The J-2 engine ignited precisely on time and burned for five minutes, raising the spacecraft’s apogee, or high point, to 10,695 miles. Ten minutes later, the CSM separated from the now empty third stage to begin testing the Apollo spacecraft. Less the two minutes after separation, the spacecraft fired its Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine for 16 seconds to increase its speed and raise the apogee to 11,244 miles. As the spacecraft coasted upward, it oriented itself to place maximum thermal stress on its heat shield. As it reached apogee five hours and 46 minutes after launch, an onboard camera took 715 high-quality color images of Earth. As Apollo 4 began its descent, it pointed its nose toward the planet and ignited the SPS engine a second time, for four minutes and 40 seconds, increasing its velocity to approximate a return from the Moon. The Command Module separated from the Service Module and used its own thrusters to reorient itself to point its heat shield in the direction of travel. At an altitude of 76 miles, while traveling at 24,974 miles per hour, the Apollo 4 Command Module encountered the first tendrils of Earth’s upper atmosphere, its heat shield absorbing the heat of reentry, reaching a temperature of 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit while the cabin temperature remained comfortable enough for a crew. After dipping down to an altitude of 35 miles, the spacecraft used its aerodynamic lift to briefly skip back out of the atmosphere, reaching a height of 45 miles before continuing the descent. This double-skip reentry reduced deceleration and heat loads on the spacecraft. At an altitude of 22,000 feet, Apollo 4 deployed its two drogue parachutes to slow and stabilize it, followed by its three main parachutes at 10,000 feet. Apollo 4 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean 12 miles from its intended target and eight miles from the prime recovery ship, the U.S.S. Bennington (CVS-20). The capsule remained upright after splashdown. The Apollo 4’s successful mission had lasted 8 hours, 27 minutes, and 9 seconds.

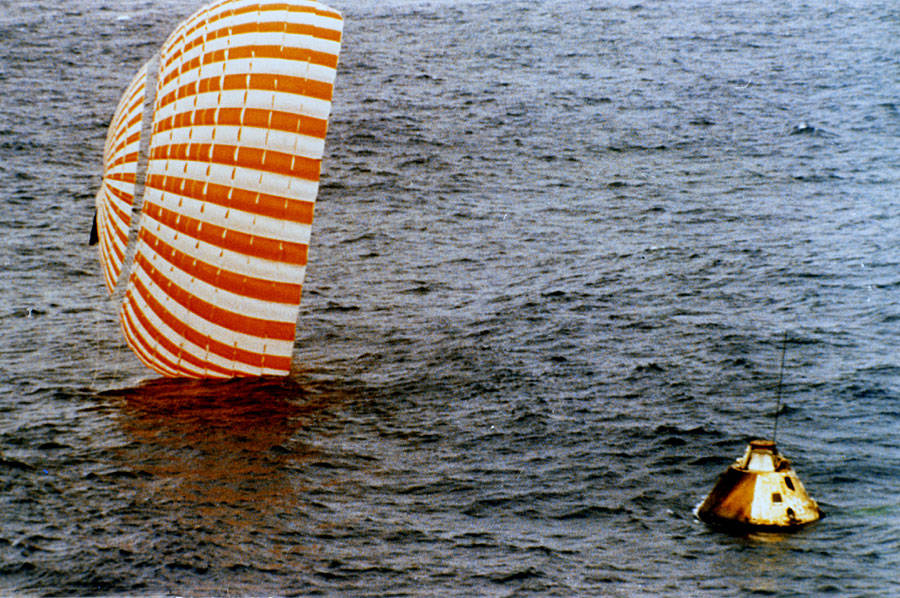

Left: Apollo 4 image of the Earth. Middle: Apollo 4 immediately after splashdown, with one of its

three main parachutes coming to rest on the water. Right: The prime recovery ship U.S.S.

Bennington approaches the Apollo 4 capsule for recovery.

Within 20 minutes of splashdown, U.S. Navy frogmen had attached a flotation collar around the spacecraft. After the Bennington pulled alongside the capsule, sailors hoisted it aboard, along with the spacecraft’s apex cover that protected the parachutes during flight and one of the three main parachutes. The entire recovery operation lasted about two hours. The Bennington sailed for Hawaii, arriving at Pearl Harbor on Nov. 11. Sailors offloaded the spacecraft and technicians shut down its systems, drained all its hazardous fluids, and deactivated pyrotechnics. On Nov. 15, crews flew the spacecraft to Long Beach, California, and then trucked it to the North American facility in Downey, California, for detailed postflight inspections. The Apollo 4 Command Module is on display at the INFINITY Center at NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Watch a NASA documentary on the mission here.

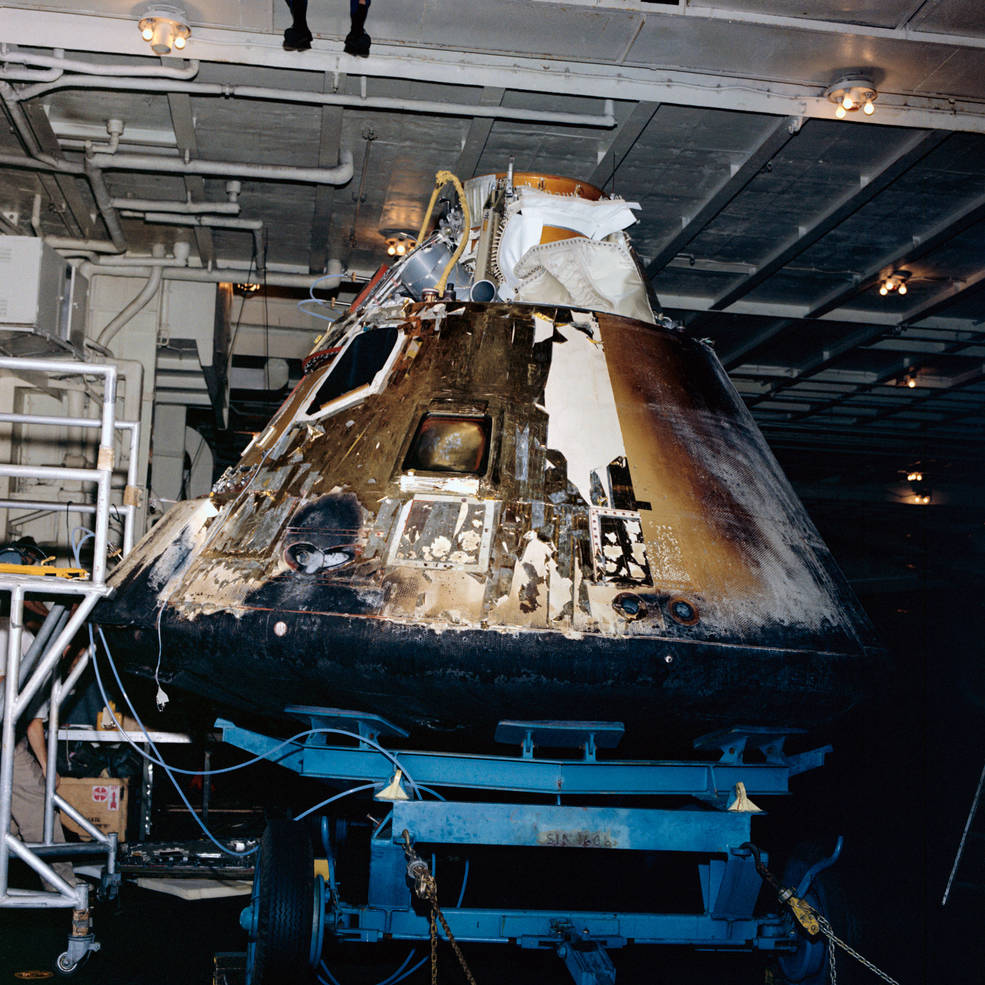

Left: Sailors prepare to hoist Apollo 4 onto the prime recovery U.S.S. Bennington.

Middle: Sailors lift Apollo 4 onto the Bennington.

Right: Apollo 4 aboard the Bennington.

Left: Robert R. Gilruth, director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s

Johnson Space Center in Houston, left, and Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager

George M. Low inspect the Apollo 4 spacecraft after its arrival at the North

American facility in Downey, California. Right: The Apollo 4 Command

Module on display at the INFINITY Center at NASA’s Stennis Space

Center in Mississippi.

The Apollo 4 mission reinvigorated the nation’s Moon landing program, struck by the tragedy of the Apollo 1 fire earlier in the year, paving the way to achieve President John F. Kennedy’s goal of “landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth” before the end of the decade. President Lyndon B. Johnson said of the flight: “The whole world could see the awesome sight of the first launch of what is now the largest rocket ever flown. This launching symbolizes the power this nation is harnessing for the peaceful exploration of space.”

Left: A Delta IV Heavy rocket lifts off carrying the Orion capsule on its EFT-1 mission.

Middle: The Orion EFT-1 following splashdown. Right: The SLS rocket topped with

an Orion capsule stands ready on Launch Pad 39B for the Artemis 1 mission.

Forty-seven years after the flight of Apollo 4, NASA conducted a very similar mission, this time to test the new Orion spacecraft, then part of the Constellation Program. The December 2014 EFT-1 mission launched an uncrewed Orion spacecraft atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket. The 4.5-hour mission flew a profile similar to Apollo 4’s, demonstrating Orion’s space worthiness. Today, another Orion spacecraft awaits its test flight atop a Space Launch System rocket as part of the Artemis Program to return astronauts to the Moon, including the first woman and the first person of color.