On July 26, 1972, NASA astronauts Robert L. Crippen, Dr. William E. Thornton, and Karol J. “Bo” Bobko embarked on a critical mission that never even left the ground. In preparation for the upcoming Skylab space station program, the astronauts conducted a 56-day simulation in an altitude chamber at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. The Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test (SMEAT) served to obtain baseline medical data on the crew and to test some of the experiment hardware and procedures planned for use aboard the space station, then planned for launch in April 1973. Conditions in the test chamber simulated the planned Skylab atmosphere. The lessons learned from SMEAT greatly enhanced the success of the Skylab missions.

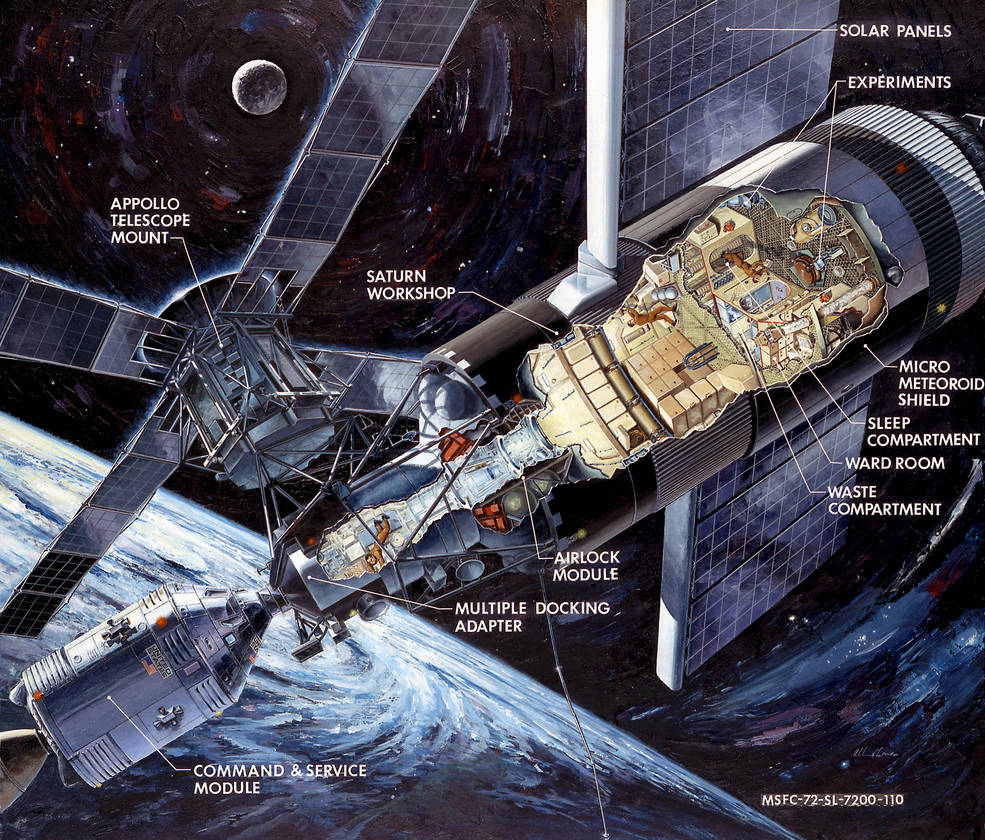

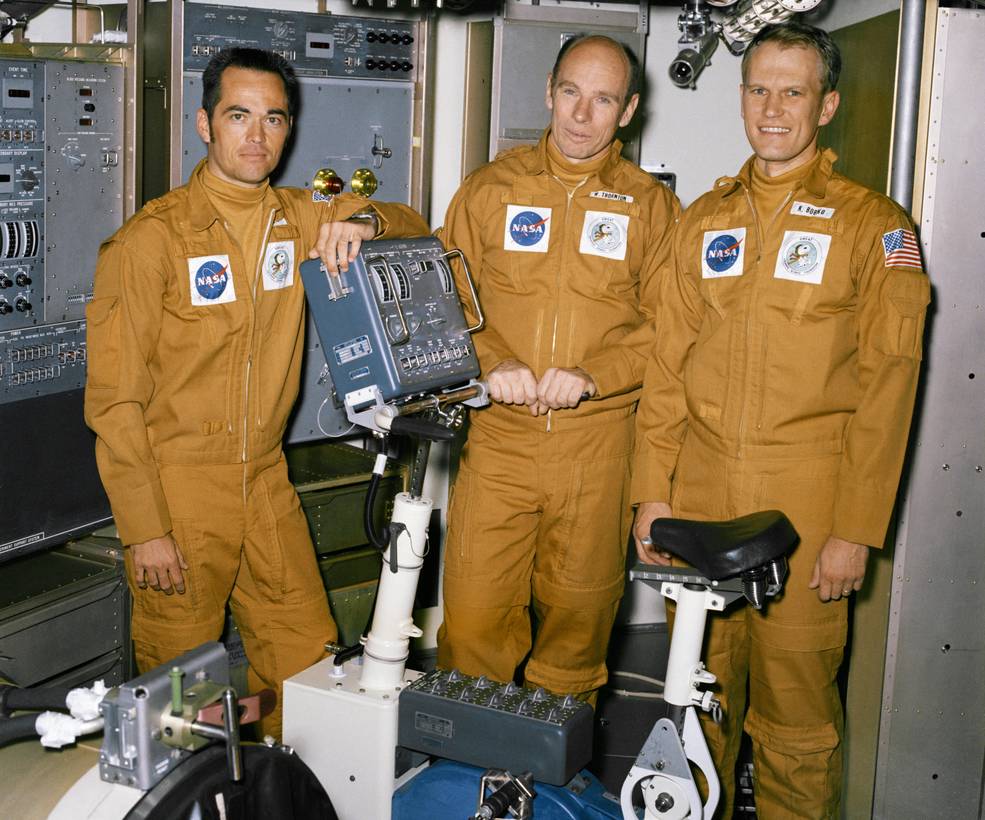

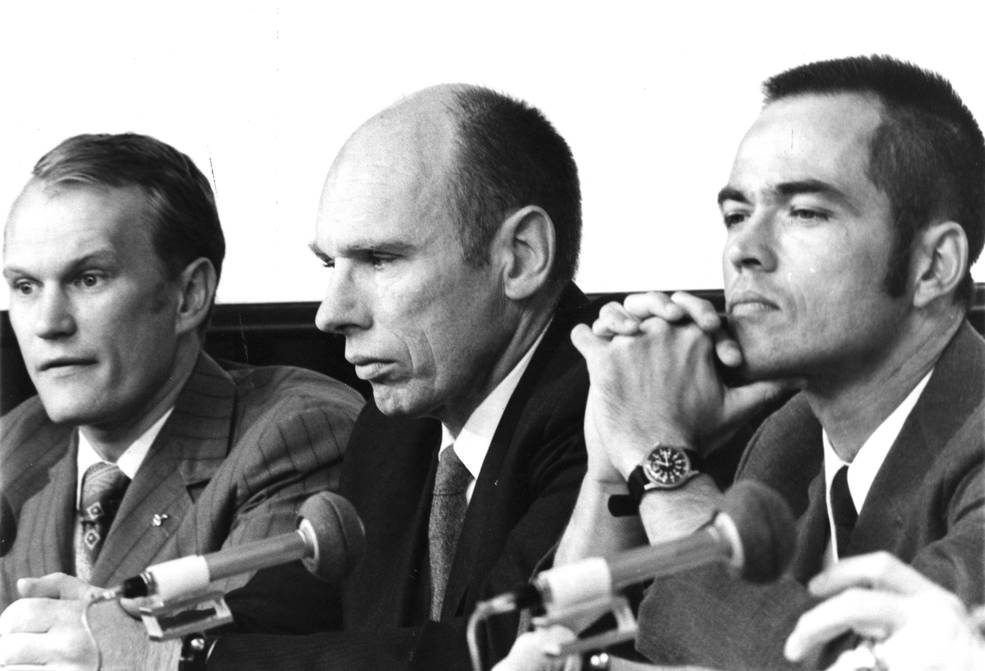

Left: Cutaway illustration from 1972 of the Skylab space station showing its main components. Right: Astronauts Robert L. Crippen, left, Dr. William E. Thornton, and Karol J. “Bo” Bobko, the Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test crew.

Skylab evolved out of the Apollo Applications Program of the mid-1960s to use Apollo hardware to establish a research facility in low-Earth orbit. NASA approved the “dry” workshop concept in July 1969 and formally named the program Skylab in February 1970. Three crews of three astronauts each would spend 28, 56, and 56 days aboard the space station, conducting research in astronomy, solar physics, Earth observations, and most importantly, to study human adaptation to long-duration spaceflight. Because Skylab enabled America’s first experience with human spaceflights longer than 14 days, NASA decided that a ground-based simulation would ensure success in orbit, approving SMEAT in February 1971. In June 1971, NASA announced the assignment of Crippen as the commander, Thornton as the science pilot, and Bobko as the pilot for SMEAT. Crippen and Bobko had served as astronauts in the U.S. Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program until its cancellation in June 1969. Two months later, they joined NASA’s astronaut corps. In addition to his medical background, Thornton had experience developing hardware, such as the Small Mass Measurement Device, for the MOL program prior to his selection as a NASA scientist-astronaut in 1967.

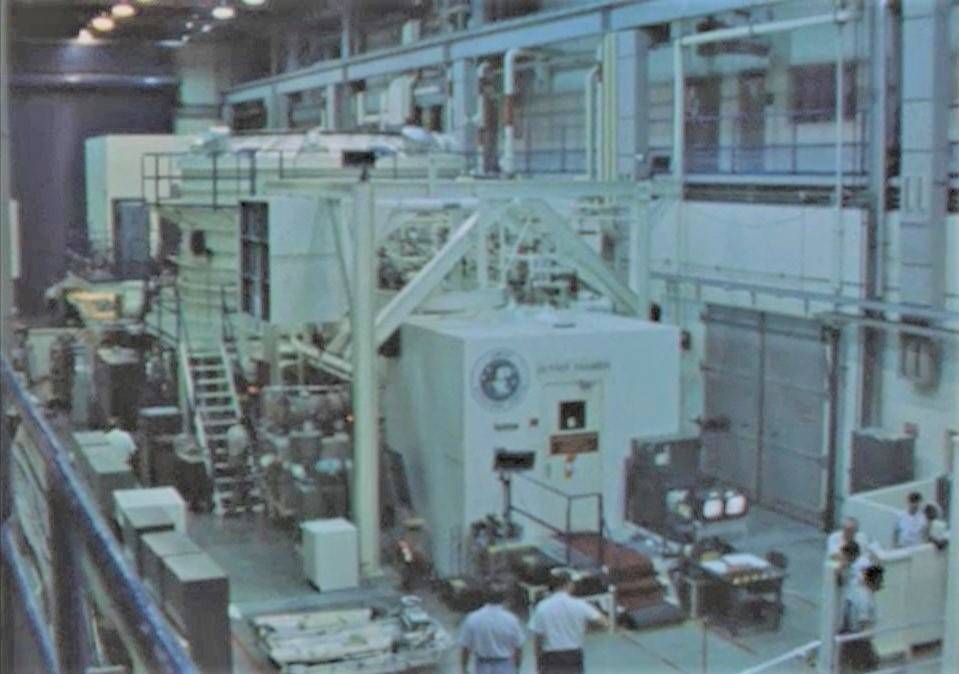

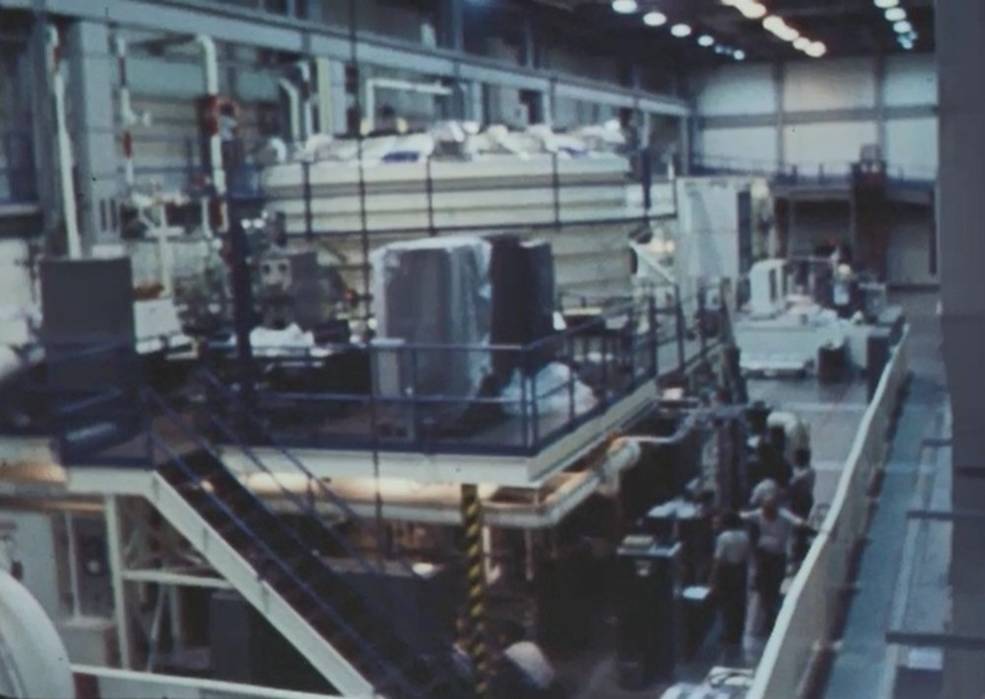

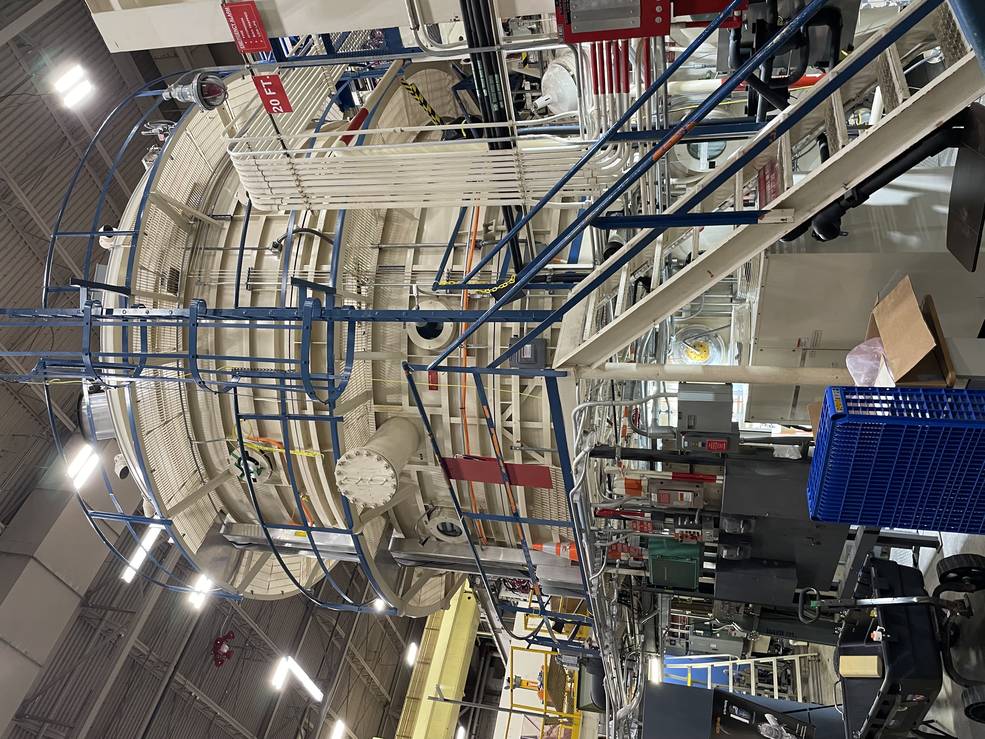

External views of the Crew Systems Division’s 20-foot altitude chamber where the 56-day Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test took place.

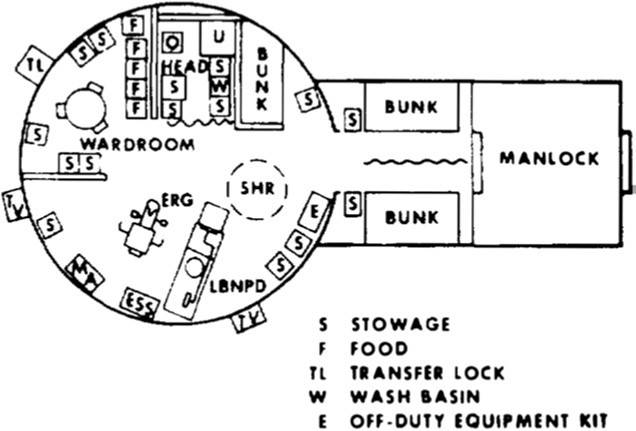

The objectives of SMEAT included acquiring baseline medical data for a set of experiments that reflect the effects of the Skylab environment (with the exception of weightlessness), evaluating selected experiment hardware and procedures, assessing medical support operations, and training the ground teams for supporting long-duration Skylab operations. The Crew Systems Division’s altitude chamber in MSC’s Building 7 served as the site for SMEAT. With its 20-foot diameter, the chamber served as a good model for Skylab’s 22-foot diameter Orbital Workshop’s lower level, the location of the crew sleep stations, the wardroom and dining table, and most of the medical experiments. Although the chamber did not have the large volume of the workshop’s upper level, its second level served as a quiet space equipped with desks and chairs for the crew to work. To simulate the planned Skylab atmosphere, the altitude chamber remained at a gas mixture of 70%oxygen and 30%nitrogen at a pressure of five pounds per square inch (psi) for the duration of the 56-day test. The astronauts entered the chamber through a manlock and used a smaller transfer lock to pass items to the outside.

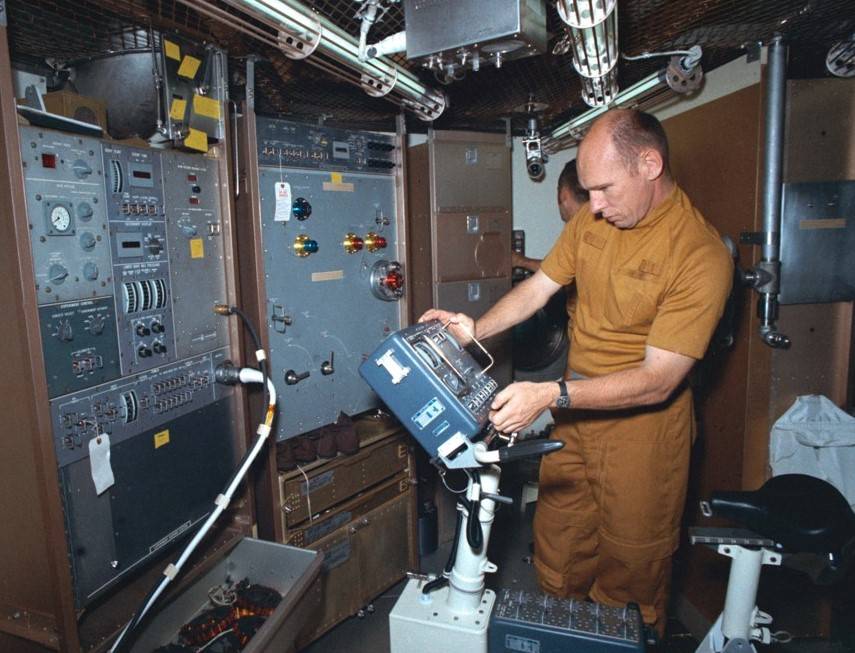

Left: Schematic of the 20-foot altitude chamber’s lower level, configured for the Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test. Acronyms not defined: ERG=ergometer, SHR=shower, LBNPD=Lower Body Negative Pressure Device. Right: Dr. William E. Thornton, left, and Karol J. “Bo” Bobko train on the Lower Body Negative Pressure Device, as Robert L. Crippen works in the background.

The astronauts began formal training for SMEAT in November 1971, with their early participation mainly in the areas of design and operational planning. The crew began training in the chamber with test equipment in March 1972. Final chamber training for the SMEAT astronauts included a 16-hour wet run and a three-day shakedown altitude run using the procedures for the actual 56-day test. The training also included a mock evacuation of indisposed crew members from the chamber. These exercises provided confidence to proceed with the long-duration test. In total, each astronaut received more than 500 hours of training to prepare for SMEAT.

Left: Robert L. Crippen trains on the wardroom table. Middle: Dr. William E. Thornton trains on the bicycle ergometer’s control panel. Right: Thornton monitors Karol J. “Bo” Bobko during a training session with the Lower Body Negative Pressure Device.

Because the Skylab activities included in SMEAT would not fully occupy the astronauts – during an actual Skylab mission, crews would also conduct astronomy, solar physics, earth observation, and other types of research – the astronauts chose additional activities, such as Russian language classes, instruction on the Apollo Command Module, and model building, to fill their time.

Left: Astronauts Karol J. “Bo” Bobko, left, Dr. William E. Thornton, and Robert L. Crippen of the Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test (SMEAT) during the pretest press conference. Right: The SMEAT crew patch.

During a press conference on June 23, 1972, MSC’s Director of Life Sciences Richard S. Johnston described SMEAT’s purpose and scientific program. The astronauts, also participating in the news conference, planned to conduct 14 of the Skylab medical experiments during SMEAT to study changes in the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, endocrine, and neurologic systems. In addition, they planned to complete 15 Detailed Test Objectives, designed to evaluate various engineering and human factors aspects of the mission. The medical tests actually began well before the astronauts entered the chamber. The plan for the metabolic experiment called for them to begin rigorously adhering to the Skylab diet and collecting urine and fecal samples 21 days before entering the chamber. When that date slipped the preflight data collection extended to 28 days. The planned 21-day pretest crew health stabilization period also lasted 28 days.

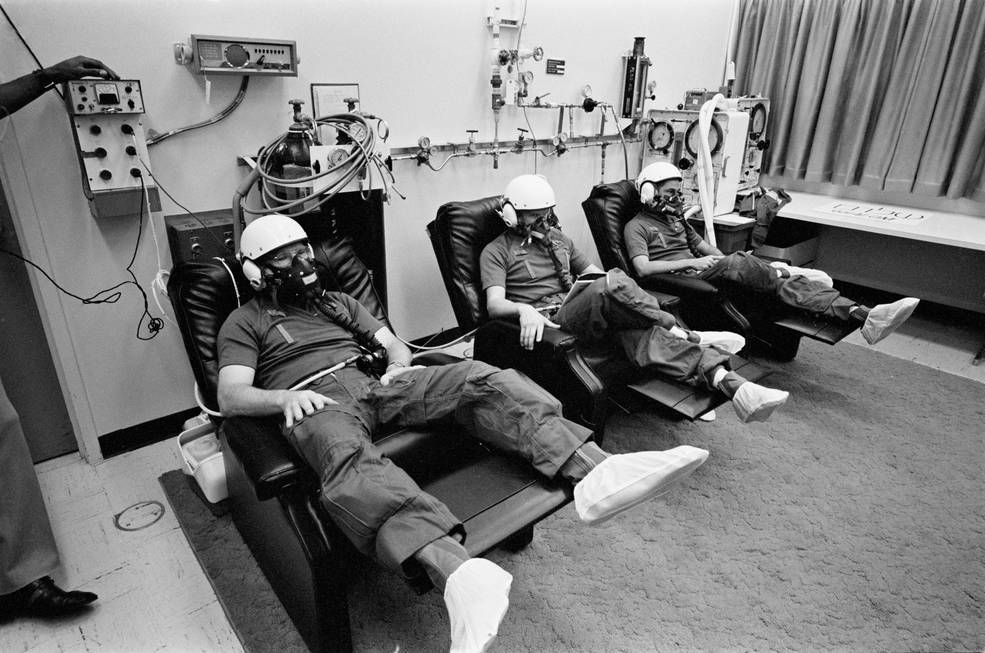

Left: Jessica B. Savitch, center, a reporter for Houston TV station KHOU, asks for a comment from astronaut Dr. William E. Thornton as he arrives to begin the Skylab Medical Experiments Altitude Test (SMEAT). Right: Astronauts Thornton, left, Karol J. “Bo” Bobko, and Robert L. Crippen breathe pure oxygen during the pretest denitrogenation.

Crippen, Thornton, and Bobko arrived in Building 7 on the morning of July 26, 1972, to begin the 56-day test. Surprisingly, some members of the media had arrived ahead of them and tried to elicit some comments as they walked by. Since planners had not included any press time in the day’s schedule, the astronauts proceeded on to their pretest physical exams, followed by a three-hour protocol during which they breathed pure oxygen through masks. The pre-breathe exercise served to purge their blood of nitrogen, a required if tedious step to prevent decompression sickness, also known as the bends, before transitioning from the 14.7 psi ambient pressure into the chamber, already depressurized to 5 psi.

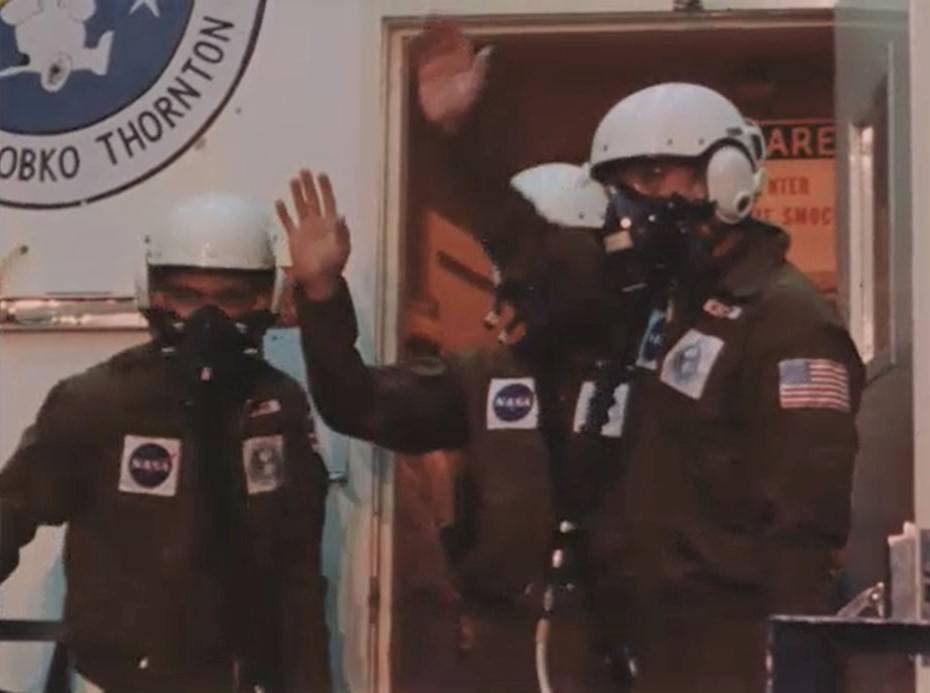

Left: Managers of the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, wish astronauts Robert L. Crippen, left, Karol J. “Bo” Bobko, and Dr. William E. Thornton good luck as they prepare to enter the chamber to begin the Skylab Medical Experiments Altitude Test (SMEAT). Right: Crippen, left, Bobko, and Thornton wave to the crowd as they enter the chamber to begin SMEAT.

Dozens of workers had gathered to see Crippen, Thornton, and Bobko enter the chamber. Several MSC managers, including Life Sciences Deputy Director W. Royce Hawkins, Skylab Program Manager Kenneth S. Kleinknecht, MSC Deputy Director Sigurd A. “Sig” Sjoberg, and Crew Systems Division Assistant Chief James V. Correale, awaited them just outside the chamber, shaking hands with the astronauts to wish them well. The trio then entered the outer door to the chamber, reappearing a few minutes later to wave one last time to the crowd. They passed through the manlock, and once technicians sealed the door, Crippen, Thornton, and Bobko officially began their 56-day stay in the chamber.

Two views of the control room for the Skylab Medical Experiments Altitude Test.

Crippen, Thornton, and Bobko settled into their new home for the next two months and began their science program. Communications with controllers on the outside proceeded as they would during an actual mission, with the astronauts talking with a capsule communicator, or capcom. The test also simulated the frequent communications outages since Skylab relied on ground stations for all space-to-ground contacts, with acquisition-of-signal periods available about 20 percent of the time. Chamber controllers had the added benefit of monitoring the crew via closed-circuit TV. As during an actual Skylab mission, principal investigator teams received experiment data in a Science Support Room in MSC’s Building 36. The astronauts experienced the first major problem during the test’s second day when the bicycle ergometer, not only the crew’s primary mode of exercise but also a vital component of the cardiovascular and metabolic experiments, failed. They passed it out through the manlock. Engineers repaired it and returned it to the chamber the next day, but with strict limits on the loads the astronauts could place on it until they could fully understand the failure mode. Four days later, engineers passed in a second ergometer so the crew could exercise at their preferred higher loads. The event highlighted the error of relying on a single mode of exercise – astronauts aboard Skylab would not have the luxury of having a new ergometer delivered to them. The ergometer continued to cause problems for the remainder of the test.

Two views of the 20-foot chamber in Building 7 of NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston in July 2022.

Astronauts Crippen and Bobko reminisce about their SMEAT experiences in their oral histories with the JSC History Office.

To be continued …

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center