Before NASA could commit Apollo 11 to make a lunar landing, the Agency required that the Lunar Module (LM) undergo a series of certification tests to ensure that the vehicle and especially its subsystems could withstand the shock of a touchdown. The Structures and Mechanics Division of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston, conducted a series of drop tests in the Vibration and Acoustic Test Facility (VATF). The LM’s manufacturer, the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, located in Bethpage, New York, provided technical support.

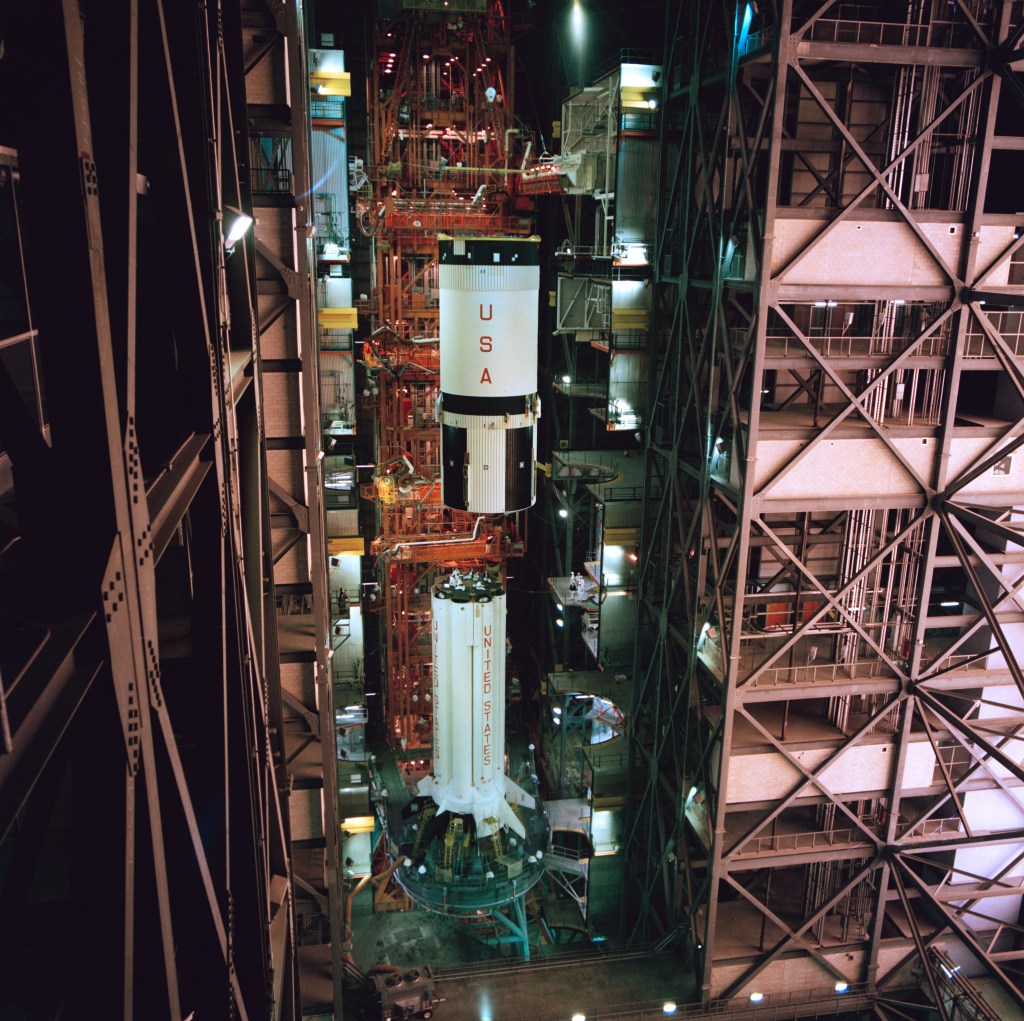

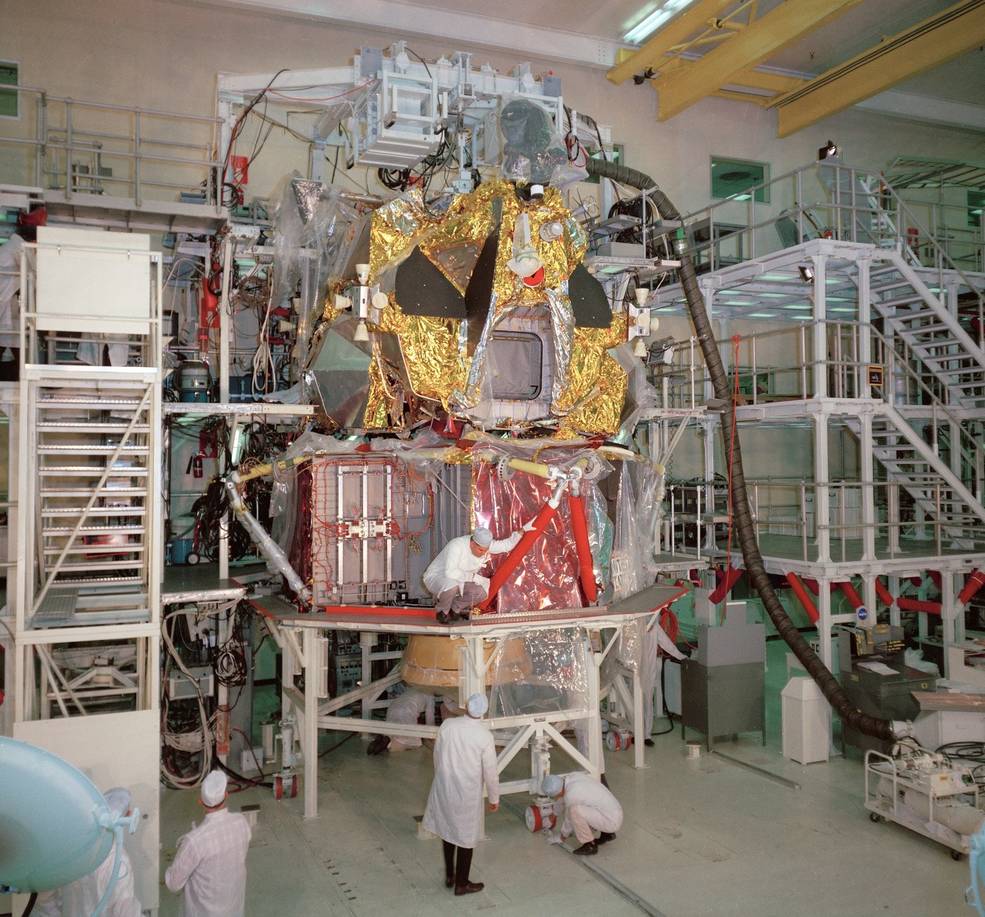

Left: LM-2 under construction at the Grumman plant. Right: The VATF at MSC.

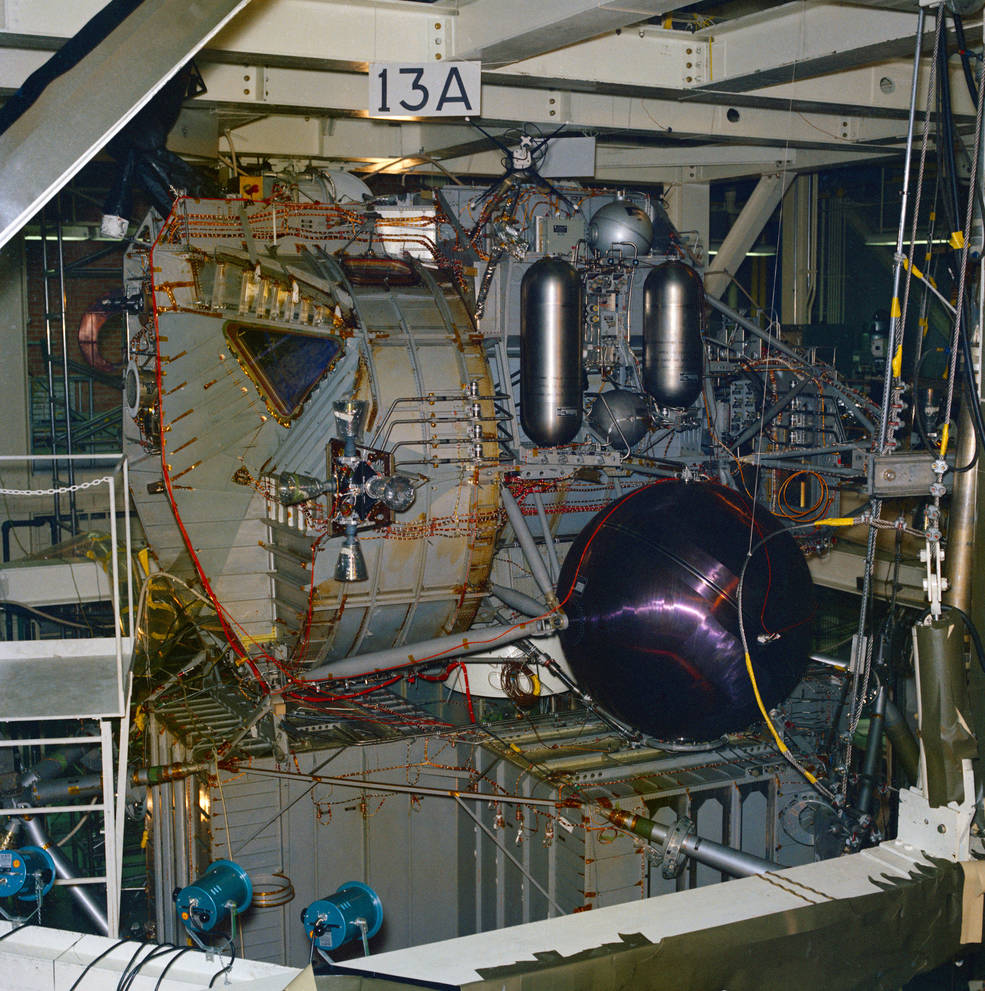

For the tests, NASA used LM-2, delivered to the Agency by Grumman in 1968 and originally planned to conduct the second unpiloted space flight test of the LM. But when the first test flight using LM-1 during the Apollo 5 mission in January 1968 went exceedingly well, NASA cancelled the second flight and decided to use LM-2 for ground testing, as it would have been prohibitively expensive to convert it to a crewed vehicle, including all the necessary fireproofing. Nevertheless, it was a flight qualified vehicle with all subsystems installed. Grumman completed a series of 16 drop tests at its facility in 1968 using a LM structural test vehicle to prove the structural integrity of the vehicle. The tests at MSC using LM-2 would verify that the vehicle’s systems would operate following a lunar landing. Landing legs were added to LM-2 to carry out the tests, since in its initial purpose as an Earth orbital unpiloted test flight, landing gear were not necessary and only added unnecessary weight. The tanks in the ascent stage were filled with inert fluid to simulate a full load of fuel, while the descent stage tanks were mostly empty, as they would be just before touchdown on the lunar surface.

Left: LM-2 in the test stand in the VATF prior to a drop test. Right: LM-2 landing leg in the VATF test stand.

The series of five tests began on March 21, 1969, and finished on May 7. Engineers dropped LM-2 from heights ranging from eight to 24 inches onto artificial slopes and obstructions to simulate landings on rough lunar terrain. The first test produced high vertical accelerations on the wire harnesses and plumbing on the spacecraft’s aft equipment bay. The second test induced lateral accelerations on the same part of the vehicle. The third test produced high acceleration loads around the inertial measurement unit and the environmental control system, while the fourth stressed the LM’s front face and side egress hatch. The fifth and final test demonstrated the capability of the ascent stage to separate from the descent stage as on liftoff and the flow of propellant in the ascent stage tanks. By removing a constraint to carrying out the first lunar landing, successful completion of the drop tests was a critical step to meet President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth before the end of the decade.

After its ground testing days were over, NASA pressed LM-2 into a different kind of service. In 1970, its ascent stage spent several months on display at the US Pavilion at “Expo ’70” in Osaka, Japan, mated to the descent stage of Lunar Test Article-8. When it returned to the United States, it was reunited with its descent stage, modified to appear like the Apollo 11 LM-5 Eagle, and transferred to the Smithsonian in 1971 for display. In 2016, curators restored and relocated it to the new Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall in the National Air and Space Museum. The Saturn 1B rocket that was originally designated to launch LM-2 came out of storage to launch the first crew to the Skylab space station in May 1973.

Left: LM-2 ascent stage on display at the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka, Japan.

Right: LM-2 modified to look like the Apollo 11 LM Eagle on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Credit: NASM

Read the JSC History Office oral histories with Robert Wren, LM-2 drop test manager.