After the excitement of their first two days on orbit, during which they completed a transposition and docking maneuver, an initial separation from, a rendezvous with, and a final separation from, their Saturn IB rocket’s S-IVB second stage, Apollo 7 astronauts Walter M. Schirra, Jr, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham settled down to conduct spacecraft checkout activities. Over the next three days, they conducted the first live television broadcasts from an American spacecraft, a third test of the Service Propulsion System (SPS), tests of the Service Module (SM) radiators and the spacecraft evaporator, and conducted radar tests with the White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) in New Mexico. To stay fit, all three astronauts spent time working out on a portable exercise device called the Exer-Genie. The colds they first reported on the first mission day seemed to improve as the flight proceeded. The crew photographed various sites on the Earth to study land and weather phenomena using a modified Hasselblad 70-mm camera. They concluded their long-distance observations of the S-IVB stage using their spacecraft’s sextant out to a distance of 320 miles. Three teams of controllers in Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston, led by Lead Flight Director Glynn S. Lunney and Flight Directors Eugene F. “Gene” Kranz and Gerald D. Griffin, working in eight-hour shifts, continued to monitor the flight.

At 49 hours and again at 51 hours, the crew conducted two tests of the primary evaporator, a component of the spacecraft’s cooling system. Engineers were pleased with the tests, declaring the evaporator to be working normally in all aspects. The astronauts conducted two tests of the rendezvous radar which would be used on later flights for docking with the Lunar Module (LM). Since this mission did not include a LM, a radar at WSMR acted as a surrogate. During passes over the station, the radar at WSMR tried to lock on to the radar transponder aboard Apollo. The first test around 71 hours was inconclusive, but during the second test the next day WSMR achieved a strong lock on the Apollo radar transponder.

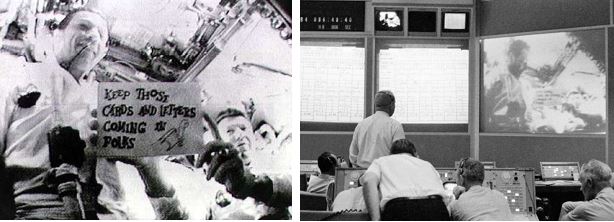

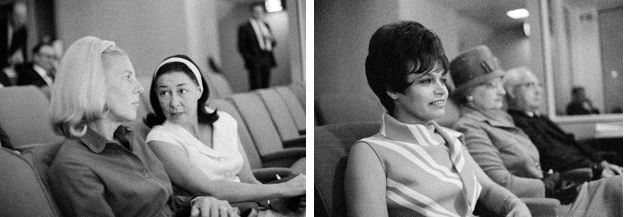

The first live TV broadcast from an American spacecraft took place about 72 hours into the Apollo 7 mission. The event had to be timed with spacecraft passes over the continental United States, because only the ground stations in Corpus Christi, Texas, and Merritt Island, Florida, had the equipment to receive the signals and convert them into the proper format for broadcasting. Jo Schirra, wife of astronaut Wally Schirra, was in the Mission Control Center’s viewing gallery with Marjorie Slayton, wife of Director of Flight Crew Operations Donald K. “Deke” Slayton, to observe the broadcast. The crew, clearly visible in their spacecraft, held up two cue cards that read “From the Lovely Apollo Room High Atop Everything” and “Keep Those Cards and Letters Coming In, Folks.” Capsule Communicator Thomas P. Stafford joked that “we’ll have Cecil B. DeStafford down here directing,” referring to award-winning filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille. The total length of the historic broadcast was seven minutes.

The third SPS burn of the mission took place at about 76 hours. The 9-second burn lowered the orbit’s perigee, or low point, from 121.5 nautical miles to 90 nautical miles to provide more propellant margin in case an early retrofire was needed. Mission Control deemed the burn successful.

Near the end of Flight Day 4, the crew began a test of the spacecraft’s radiators, consisting of two banks located on the outside of the SM. One bank was kept pointed down toward the Earth while the opposite bank was kept pointing out toward deep space. The radiators performed as expected during the 4.5-hour test, validating the system for lunar flights.

The second TV broadcast took place at about 95 hours (nearly 4 days) into the mission. The crew provided a tour of their spacecraft, demonstrating how spacious it was compared to previous American capsules, and highlighting several of the instrument panels. The crew held up two cue cards with the questions, “Are you a turtle, Deke Slayton?” and “Paul Haney, are you a turtle?” The latter question, addressed to the Director of Public Affairs at MSC, Neither man provided an immediate response as required by the inside joke. Slayton had recorded his answer to be played to the crew after the mission, while Haney could not be reached for comment. Harriett Eisele, the wife of astronaut Donn Eisele, was in the viewing gallery in Mission Control along with her parents, to watch the 11-minute TV broadcast.

At about 119 hours (nearly 5 days) into the mission, the crew conducted the third TV broadcast of the flight. During this 11-minute broadcast, the astronauts demonstrated food preparation techniques, explaining that for the first time on an American spacecraft hot food was available using a hot water dispenser to rehydrate food packages. They also demonstrated how they’ve been vacuuming some small puddles of water condensate and dumping them overboard. Cunningham’s wife Lo and brother Bill, visiting from Alaska, were in the viewing gallery for the TV broadcast.

After five days in orbit, both the crew and the spacecraft were performing very well. Since Apollo 7 was an open-ended mission, Flight Directors gave the crew daily permissions to continue the flight. So far, there were no issues that would prevent a full-duration 11-day mission.