It was Christmas Day 1968, and after spending 20 hours orbiting the Moon, the Apollo 8 crew of Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders was on its way back to Earth. The Trans Earth Injection burn by the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine was very precise, and only one midcourse correction was needed during the trip home. Initially speeding at more than 6,000 miles per hour, the spacecraft began slowing down as the Moon’s gravity exerted its force upon it. At about 100 hours and 48 minutes into the mission, Apollo 8 crossed back into the Earth’s sphere of influence, where the home planet exerted the greatest force on the spacecraft, and began gradually speeding up. Meanwhile, the pace of activities aboard the spacecraft decreased significantly and the crewmembers were able to get some much needed rest, having slept only about two hours each during their lunar orbit time. They placed their spacecraft back into Passive Thermal Contol or barbecue mode to even out the extreme temperatures in space. During this time, astronaut Borman’s wife Susan, accompanied their two children and Borman’s parents paid a visit to the Visitors Gallery in Mission Control.

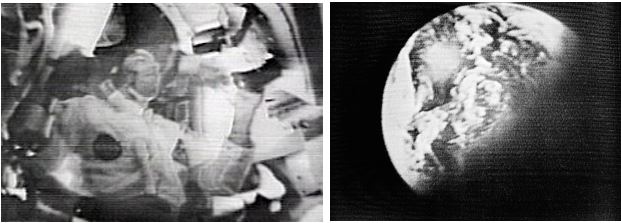

The astronauts carried out the only required midcourse maneuver at 104 hours into the mission, a 14-sec burn to adjust the spacecraft’s trajectory for the proper entry corridor into Earth’s atmosphere. Shortly thereafter, they began a 10-minute TV broadcast. The internal cabin scenes included Lovell exercising, the spacecraft’s computer and navigation device, and the trio enjoying a Christmas dinner. The final TV broadcast of the mission occurred the next day and included spectacular views of the Earth out the spacecraft’s window. Lovell’s wife Marilyn and two of their four children were in the Mission Control Visitors Gallery for this last TV pass. After their last sleep period in space, the astronauts turned their attention to the entry back into Earth’s atmosphere.

About 15 minutes before Entry Interface, a point 400,000 feet (about 75 miles) in altitude where the spacecraft began to encounter the outermost fringes of the Earth’s atmosphere, the crew jettisoned the Service Module and turned the Command Module (CM) around so its heat shield was facing in the direction of flight. At that point, there were traveling at 24,695 miles per hour, the highest velocity ever achieved by humans. As they traveled into ever denser layers of the atmosphere, their velocity decreased dramatically, with the deceleration imparting forces up to 7 Gs, or seven times Earth’s gravity. Temperatures outside the spacecraft reached 5,000 degrees but the crewmembers inside the spacecraft remained at room temperature thanks to the protection of the heat shield. A sheath of ionozed gases formed around the capsule during reentry prevented communications between the spacecraft and Mission Contorl, resulting in a brief three-minute blackout period. At about 35 miles altitude, using the vehicle’s aerodynamic lift properties to minimize heating, the spacecraft actually raised its altitude back up to about 40 miles before resuming its descent, but it did not leave the atmosphere as in a true skip-reentry profile. Coming out of the blackout, Borman radioed about the reentry, “This is a real fireball!”

Following entry, a rapid sequence of events slowed the spacecraft all the way to splashdown. With Apollo 8 at 23,000 feet altitude, two drogue parachutes opened to slow the spacecraft to about 200 miles per hour, followed at 10,000 feet by the three main parachutes. Apollo 8 spalshed down at a mere 21 miles per hour, within 5,000 yards of the prime recovery ship the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown. Landing occurred at 165 degrees west longitude and 8 degrees and 8 minuted north latitude, 600 miles northwest of Christmas Island and 900 miles southwest of Hawaii. Borman, Lovell, and Anders were in excellent health after a flight of 147 hours that took humanity to lunar orbit for the first time. Of the 6.5 million pounds at liftoff, less than 11,000 pounds comprising the CM came back to Earth.

Operations Christopher C. Kraft (left) and Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager George M. Low (right).

Right: Apollo 8 astronauts (left to right) Anders, Borman, and Lovell are welcomed home at Houston’s Ellington AFB.

Within 90 minutes, a helicopter picked up the astronauts from the water and brought them onto the deck of the Yorktown, where the ship’s captain and crew greeted them with cheers. In Mission Control, controllers unfurled a 10-foot-by-15-foot American flag, displayed smaller flags at every console, and managers passed around cigars to celebrate the success of Apollo 8. Back on the recovery ship, after a quick shower and medical checkup, the astronauts took a call from President Lyndon B. Johnson who congratulated them on an outstanding mission. The next day, they took a helicopter to Hickam Air Force Base (AFB) in Hawaii and then boarded a transport plane back to Houston’s Ellington AFB where they were met by their families and cheering well-wishers. No one seemed to mind that it was 2 AM. Although much work still remained in the Apollo program, including testing the Lunar Module in space, the likelihood of meeting President John F. Kennedy’s goal of a Moon landing before the end of the decade seemed much higher after the success of Apollo 8.

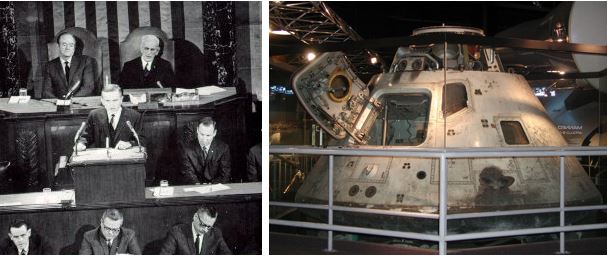

The Apollo 8 astronauts received many accolades for their successful mission. The trio spoke before a joint session of Congress on Jan. 9, 1969. Two presidents honored the Apollo 8 crew at the White House for its outstanding achievement – outgoing President Johnson on Jan. 10, and newly inaugurated President Richard M. Nixon on Feb. 3. TIME magazine designated them Men of the Year for 1968. For their historic TV broadcasts, the Apollo 8 astronauts, like their predecessors on Apollo 7, were awarded Emmy Awards, the highest honor paid by the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. The Apollo 8 spacecraft also received postflight attention. In January 1970, the United States delivered the CM for display at the Osaka World’s Fair. The capsule is now on display at the Chicago Museum of Science+ Industry.

Apollo 8’s legacy went beyond just taking a huge step toward the Moon landing. Both in the United States and around the world, 1968 was a turbulent year, and the flight around the Moon gave people hope for the future. A telegram from an unknown well-wisher to Frank Borman perhaps summed it up best: “Thank you Apollo 8. You saved 1968.” And the famous Earthrise photo taken during the mission is often credited with giving impetus to the environmental movement and inspiring the first Earth Day in 1970.