Space shuttle Columbia took to the skies on June 27, 1982, to begin its fourth trip into space. Astronauts Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield rode the reusable spacecraft on a pillar of fire from Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. The STS-4 mission, the last of the program’s four orbital flight tests, featured the first shuttle payload sponsored by the Department of Defense (DOD). Mattingly and Hartsfield continued engineering tests of the reusable spacecraft including characterizing its thermal properties and its contamination environment. At the end of the seven-day mission, they made the first shuttle landing on a concrete runway, arriving home to a presidential welcome and a Fourth of July celebration with three space shuttle orbiters.

Left: Official photo of the STS-4 crew of Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield, left, and

Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly. Right: Official STS-4 crew patch.

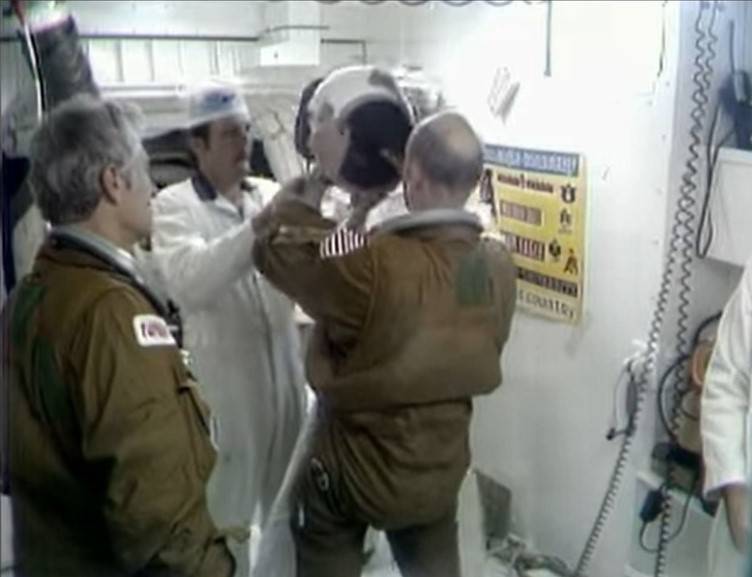

The STS-3 mission concluded on March 20, 1982, when space shuttle Columbia landed at Northrup Strip at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Ground crews returned the orbiter to KSC and refurbished the vehicle for the upcoming STS-4 mission in what was then record time, rolling the stack out to Launch Pad 39A on May 26. The 90-hour countdown for STS-4, slightly longer than usual to accommodate loading of super-cold helium into the DOD’s Cryogenic Infrared Radiance Instrumentation for Shuttle (CIRRIS) payload, commenced on June 23. Engineers and managers in Firing Room 1 of the Launch Control Center monitored the activities. Flying in from Houston’s Ellington Air Force Base (AFB), Mattingly and Hartsfield touched down on KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility on June 25, their arrival diverted from nearby Patrick AFB and delayed 40 minutes due to local thunderstorms. To prepare for the launch two days later, they reviewed their mission plan and practiced landings in the Shuttle Training Aircraft. On launch morning, they ate the traditional breakfast with mission managers, donned their launch and entry pressure suits, and rode the astronaut van to the launch pad.

Left: STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly, left, and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield

depart crew quarters, accompanied by Director of Flight Operations George W.S. Abbey.

Middle: In the White Room at Launch Pad 39A, Hartsfield, left, and Mattingly prepare

to board Columbia. Right: View of Firing Room 1 in the Launch Control

Center during the STS-4 countdown.

At precisely 11 a.m. EDT on June 27, 1982, just three months after its previous launch, space shuttle Columbia lifted off from Launch Pad 39A, riding on the thrust of its two solid rocket boosters and its three main engines. As soon as the shuttle cleared the launch tower, control of the flight handed over to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston. The Ivory Team of flight controllers led by ascent Flight Director Thomas W. “Tommy” Holloway monitored Columbia’s ascent, with capsule communicator (capcom) astronaut S. David Griggs relaying milestone events to Mattingly and Hartsfield aboard the shuttle. About two minutes after liftoff, the two solid rocket boosters (SRBs) exhausted their fuel and were jettisoned. Due to parachute malfunctions, both SRBs sustained heavy damage upon water impact and sank in the Atlantic Ocean. Columbia continued its ascent on the power of its three main engines. Eight and a half minutes after liftoff, Columbia’s main engines shut off on time and the large external tank was jettisoned. The space shuttle had reached space but had not yet achieved orbit. Columbia’s two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines fired twice to complete the task of placing the vehicle into a circular 150-mile-high orbit. Mission Control gave Mattingly and Hartsfield a “go” to stay in orbit. The first major task involved opening the orbiter’s payload bay doors to allow the radiators mounted inside them to cool the vehicle. They removed their launch and entry pressure suits and changed into more comfortable flight suits. Mattingly and Hartsfield had company in space, as they joined another crew already in orbit aboard the Soviet Salyut 7 space station – four Soviet cosmonauts and a visiting guest astronaut from France. The seven crew members tied the then-record for the most people in space at the same time, first set in 1969.

Left: Liftoff of STS-4 on Columbia’s fourth trip into space. Right: In Firing

Room 1 of the Launch Control Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in

Florida, launch controllers watch the ascent of space shuttle Columbia

after handing control of the mission over to the Mission Control

Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

View in the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in

Houston during the first day of the STS-4 mission.

Although many aspects of the mission remain classified due to the DOD payload aboard Columbia, NASA made public other portions of the flight. One of the first changes to the mission’s timeline involved the thermal tests on the vehicle, in which the orbiter would spend several hours in various attitudes to measure the effects of extreme temperature on the spacecraft’s structures. Because of severe thunderstorms at the pad the day prior to launch, mission managers requested that, instead of the planned attitude with the payload bay facing the Earth, Columbia be placed first in an attitude with its belly facing the Sun, to bake out any water remaining in the heat shield tiles in the event of a possible early reentry. Mattingly and Hartsfield reported that the CIRRIS instrument in the payload bay did not operate, setting off several days of trouble-shooting activities that unfortunately did not recover the experiment. Two additional OMS burns raised the orbit to a circular 185 miles. After a long day, Mattingly and Hartsfield settled down for their first night’s sleep in space.

Left: STS-4 astronaut Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield demonstrates the sleeping bag on

Columbia’s middeck. Middle: Hartsfield works on the Continuous Flow Electrophoresis

System experiment. Right: Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly conducts the Nighttime

Daytime Optical Survey of Lightning experiment.

After a short night’s sleep, Mission Control woke the crew with the song “Up, Up and Away (In My Beautiful Balloon)” by The 5th Dimension. Mattingly and Hartsfield reported that the Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System appeared to be operating well, as were other middeck experiments. The major activity of the day involved activating the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS), or robotic arm, and use it to pick up the Induced Environment Contamination Monitor (IECM) and move it around to different positions in the payload bay to sample any contaminants. The 850-pound IECM set a record as the heaviest object lifted by the RMS up to that time. The contamination study continued into the next day, with the experiment taking samples following the release of a mixture of hydrogen and neon gas while the orbiter changed its attitude. Hartsfield celebrated his 26th wedding anniversary, with his wife Judy sending him a recorded message.

Left: Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly prepares a meal on Columbia’s middeck.

Right: Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield practices donning the launch and

entry pressure suit in the middeck.

On the mission’s fifth day, with the orbiter in the belly-to-the-Sun orientation, Mattingly and Hartsfield practiced closing the payload bay doors that had been in shadow during this time. The cold had warped the doors sufficiently that the port side one did not close properly. With a change in attitude to warm the doors, they eventually closed and re-opened properly. The activity demonstrated the value of conducting the thermal tests on the vehicle. Later in the day, the astronauts performed another OMS burn to raise their orbit to 195 by 186 miles, the highest altitude achieved by the shuttle to that time.

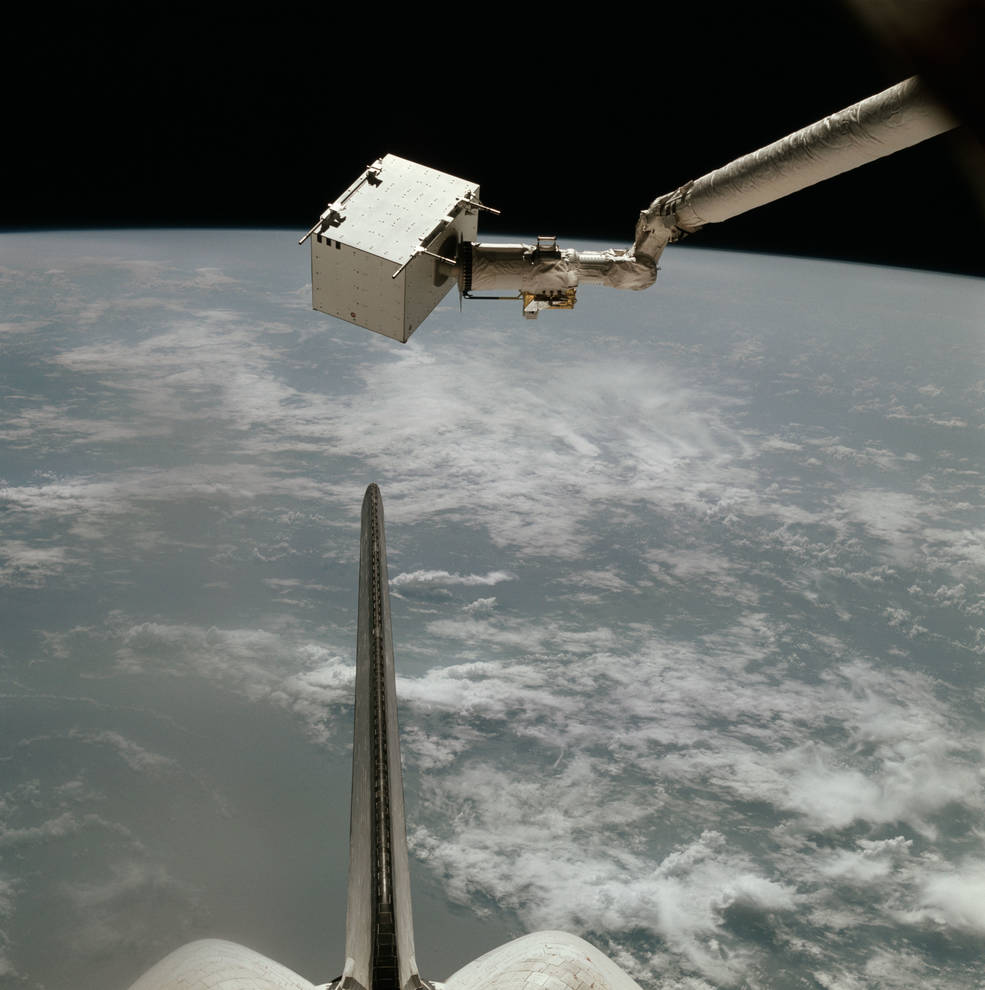

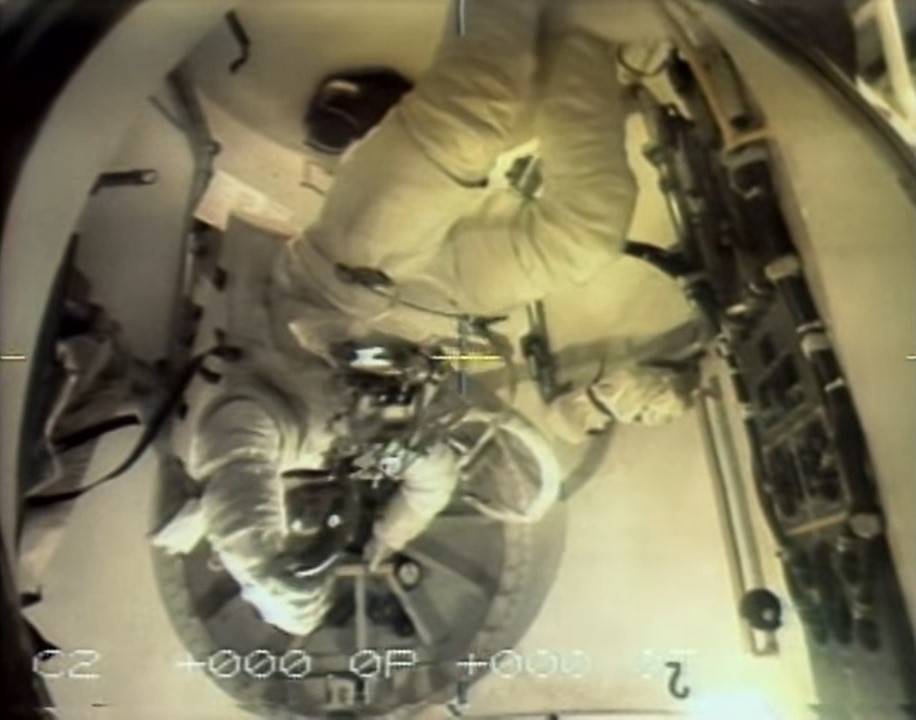

Left: The shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System holding the Induced Environment Contaminant

Monitor experiment above Columbia’s payload bay. Middle: Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly tests the

space shuttle Extravehicular Mobility Unit spacesuit in Columbia’s airlock, the first

inflight test of the suit designed for spacewalking. Right: Henry W. “Hank”

Hartsfield holding the printout from the teletype machine outlining all the

changes to the day’s flight plan.

Mission Control awakened the crew on flight day 6 with music from “Chariots of Fire.” The main activity for the day involved Mattingly putting on an Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU), the suit designed for spacewalks, in Columbia’s airlock. Although the STS-4 timeline did not include a spacewalk, Mattingly had trained on the ground for a contingency spacewalk, for example to manually close the payload bay doors if needed. With a spacewalk planned for STS-5, Mattingly believed testing the spacesuit on this flight seemed prudent. Although mission controllers had not rehearsed the activity before the flight, Mattingly completed the task successfully. Small burns on flight day 6 and 7 using the shuttle’s Reaction Control System thrusters raised Columbia’s orbit slightly, to 202 by 183 miles, to prepare for the deorbit burn and reentry on flight day 8.

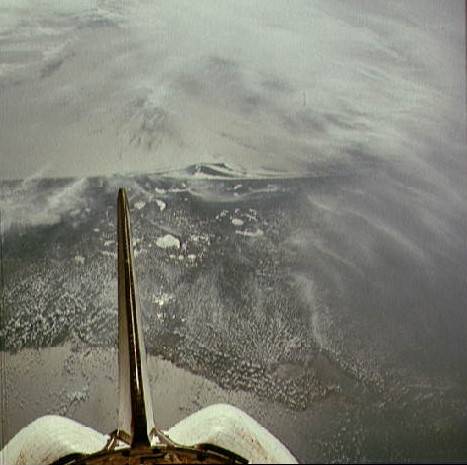

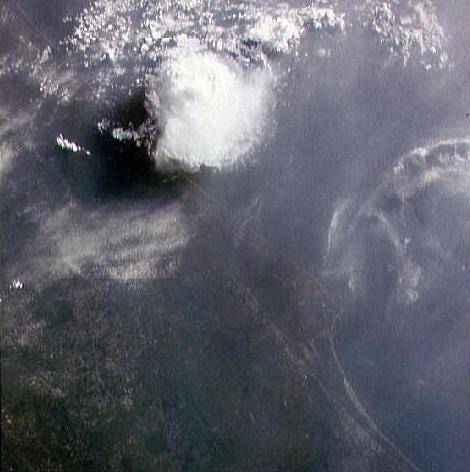

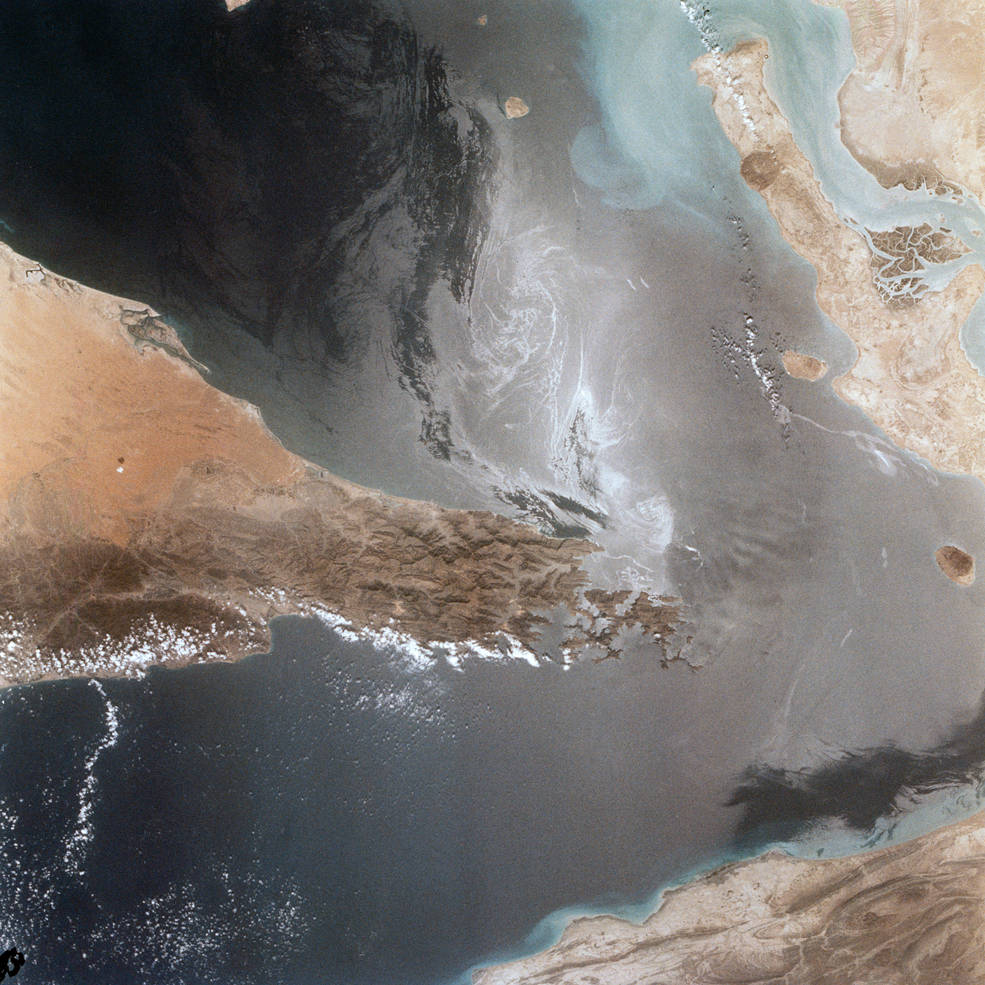

Four of the Earth observation photographs taken by STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly

and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield – Florida including NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, left, a

thunderstorm off the east coast of the United States, the Sargasso Sea,

and the Straits of Hormuz.

On their final day in orbit, as Mattingly and Hartsfield became the first Americans in space on the Fourth of July, Mission Control awakened them with the appropriately patriotic tune, “This is My Country.” To begin their deorbit preparations, they closed Columbia’s payload bay doors, donned their pressure suits, and oriented the vehicle with its OMS engines facing in the direction of travel. Entry Flight Director Harold M. Draughon gave them a “go” for the deorbit burn, and they fired Columbia’s OMS engines over the Indian Ocean for nearly three minutes to drop the spacecraft out of orbit. Twenty-seven minutes later, Columbia encountered the first tendrils of the Earth’s upper atmosphere at an altitude of 400,000 feet. The heat of reentry caused a sheath of ionized plasma to form around the vehicle, blocking communications for 16 minutes. They crossed the California coast at an altitude of 112,000 feet, traveling at Mach 4. By the time they flew a circle over Edwards Air Force Base in California’s Mojave Desert, they had dropped to 50,000 feet. Mattingly took over manual control at 2,500 feet and guided Columbia to a smooth landing on Runway 22, the first shuttle touchdown on a concrete runway. Columbia rolled to a stop, completing a mission of 7 days, 1 hour, and 10 minutes. “Welcome back to Earth,” capcom Brewster H. Shaw radioed from Mission Control. “That looks like a beautiful vehicle.”

Left: TOUCHDOWN! Columbia makes the first space shuttle landing on the concrete runway

at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Middle: President Ronald W. Reagan and

First Lady Nancy Reagan greet STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly and

Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield following their landing. Right: Mattingly and

Hartsfield take the Reagans on a postflight inspection tour of Columbia.

A crowd estimated at 525,000 had gathered in the viewing area of Edwards AFB. President Ronald W. Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan greeted Mattingly and Hartsfield on the runway as they walked down the stairs after exiting Columbia. They completed an abbreviated walkaround inspection of the orbiter, with the President and First Lady both touching the nose landing gear door of Columbia that had been in space an hour earlier. In Mission Control, flight controllers cheered and waved American flags following what Flight Director Draughon called “one of the cleanest flights yet.“

The Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston

shortly after the STS-4 landing.

Three views of the Fourth of July reception for the returning STS-4 crew of Thomas K. “TK”

Mattingly and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield, held at NASA’s Dryden (now Armstrong) Flight

Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California and attended by President

Ronald W. Reagan, First Lady Nancy Reagan, and NASA Administrator James M. Beggs,

with space shuttle Enterprise as a backdrop.

About an hour later, with space shuttle Enterprise as a backdrop, NASA Administrator James M. Beggs introduced President Reagan who saluted Mattingly and Hartsfield, saying “TK and Hank, you’ve just given the American people a Fourth of July present to remember.“ Near the end of his speech, the President gave the go-ahead for the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) with NASA’s newest space shuttle, Challenger, perched on top to take off on the first leg of its journey to KSC. The SCA with Challenger made a pass over the assembly during Mattingly’s speech, and made a second pass following Hartsfield’s comments, dipping a wing in salute. Despite the desert heat, an estimated 45,000 people attended the ceremony in person while millions watched on television. For about two hours, Edwards AFB hosted three space shuttle orbiters, the first time ever.

Left: Space shuttle Challenger departs Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in California atop its

Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA). Middle: Challenger atop its SCA photographed in mid-air

following departure from Edwards AFB. Right: STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly

and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield and a crowd of well-wishers greet Challenger atop

its SCA upon their arrival at Ellington AFB in Houston.

The SCA/Challenger duo headed east for their first stop at Ellington AFB in Houston, a few miles from JSC. Mattingly and Hartsfield, accompanied by their wives, boarded a Gulfstream jet. Aboard the speedier aircraft, they arrived at Ellington about 30 minutes ahead of Challenger. A crowd of several thousand well-wishers had gathered to welcome the STS-4 crew and the newest addition to the growing shuttle fleet. NASA Deputy Administrator Hans M. Mark introduced Mattingly and Hartsfield. The SCA landed during Mattingly’s speech, the engine noise drowning out his comments. The ceremony paused as the jumbo jet carrying Challenger taxied to its overnight parking position. Following the ceremony, the crowd turned its attention to admiring the SCA and Challenger.

Left: STS-4 astronaut Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly, right, addresses the crowd at

Ellington Air Force Base in Houston, as fellow crew member Henry W. “Hank”

Hartsfield and NASA Deputy Administrator Hans M. Mark listen. Right: Space

shuttle Challenger atop its Shuttle Carrier Aircraft sits on an apron

at Ellington, during an overnight stop on its way to NASA’s

Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The next morning, the SCA carrying Challenger took off from Ellington, arriving at KSC’s SLF later that day. It taxied to the Mate Demate Device (MDD) where ground crews lifted the orbiter off the SCA. On July 6, workers towed Challenger to the nearby Orbiter Processing Facility to begin preparing it for its first mission, STS-6, then planned for January 1983.

Left: Space shuttle Challenger atop its Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) arrives

at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida on July 5, 1982.

Right: Space shuttle Columbia arrives back at KSC on July 15.

Meanwhile at Dryden, ground crews towed Columbia from Runway 22 to that center’s MDD for a postflight inspection, finding it in remarkably good shape. They mounted it on top of the SCA after it returned from delivering Challenger to KSC. The SCA/Columbia duo departed Edwards AFB on July 14, and after a refueling stop at Dyess AFB in Texas, arrived at KSC to begin processing for its next mission, STS-5, planned for November 1982.

Left: During a postflight debrief, STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly

and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield are joined by the four-man STS-5 crew

and NASA managers. Right: Mattingly, left, and Hartsfield during

their postflight crew press conference.

Back in Houston, Mattingly and Hartsfield returned to work for a series of debriefs with management and the four members of the STS-5 crew, eager to learn the lessons they learned on their test flight. On July 19, Mattingly and Hartsfield held a press conference during which they narrated a video about their mission and answered reporters’ questions. Of the space shuttle, Mattingly said, “This agency has put together one of the most spectacular pieces of machinery that you can ever imagine.” Hartsfield agreed, saying, “We do have a reusable vehicle, a reliable vehicle, and a highly versatile vehicle.”

To be continued…