Preparations were in full swing in May 1982 to ready space shuttle Columbia for its fourth trip into space. The STS-4 mission, planned for launch on June 27, was the fourth and final mission in the Orbital Flight Test program. At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, teams closed Columbia’s payload bay doors, towed it to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), joined it with its external tank and solid rocket boosters, and rolled the stack out to Launch Pad 39A. Astronauts Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield participated in a countdown demonstration test while ground crews completed a cryogenic fuel loading test of Columbia’s external tank. At NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Mattingly and Hartsfield held a press conference and took part in a long simulation of their upcoming flight with mission controllers.

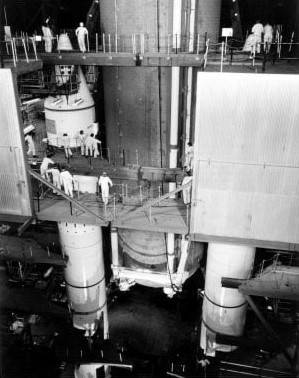

Left: The External Tank (ET) for the STS-4 mission arrives at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Middle: Workers tow space shuttle Columbia from the Shuttle Landing Facility to the Orbiter Processing Facility following the STS-3 mission. Right: Ground crews in the Vehicle Assembly Building lower the ET for mating with the two Solid Rocket Boosters.

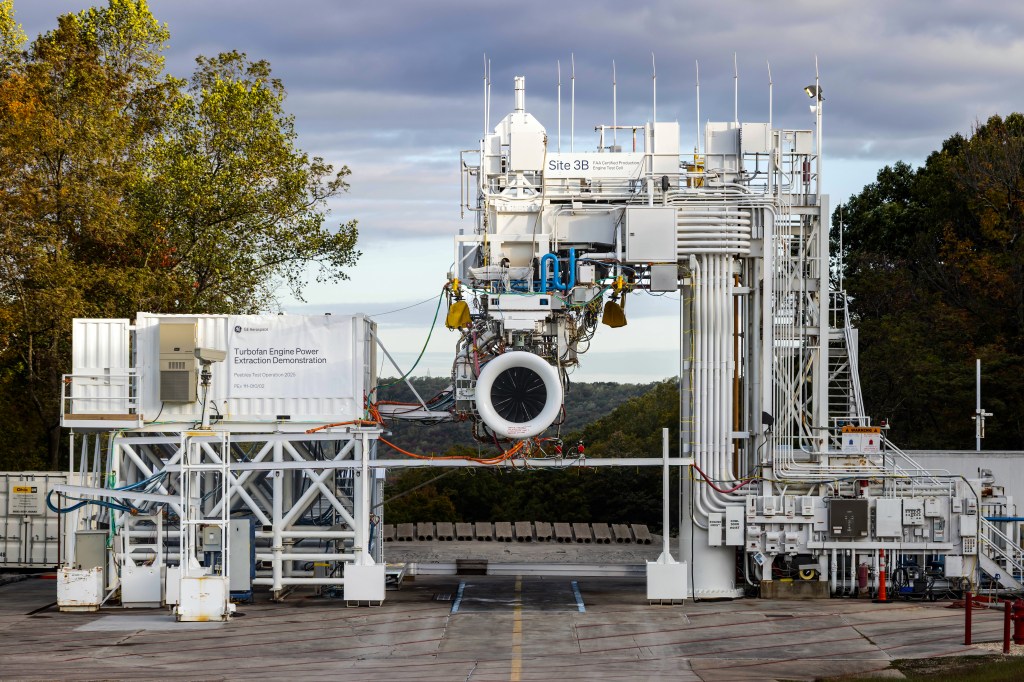

The STS-3 mission ended on March 30, 1982, when space shuttle Columbia landed at Northrup Strip at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Columbia then traveled to KSC’s Shuttle Processing Facility atop its Shuttle Carrier Aircraft on April 6. Workers demated the orbiter the next day and towed it to the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) for postflight processing, including removal of the payloads from the cargo bay on April 13. Meanwhile, in the VAB’s High Bay 3, workers began stacking the segments of the twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) on Mobile Launch Platform-1 (MLP-1) on March 29, completing the task on April 8. On April 16, workers began attaching the large External Tank (ET), undergoing testing in the VAB since Jan. 22, to the SRBs, completing the task in record time the next day.

Left: Ground crews in the Vehicle Assembly Building prepare to rotate space shuttle Columbia to a vertical orientation to begin the stacking process. Middle: Workers lift Columbia to hoist it to High Bay 3 for mating with the External Tank (ET) and Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). Right: Workers lower Columbia for mating with the ET and SRBs.

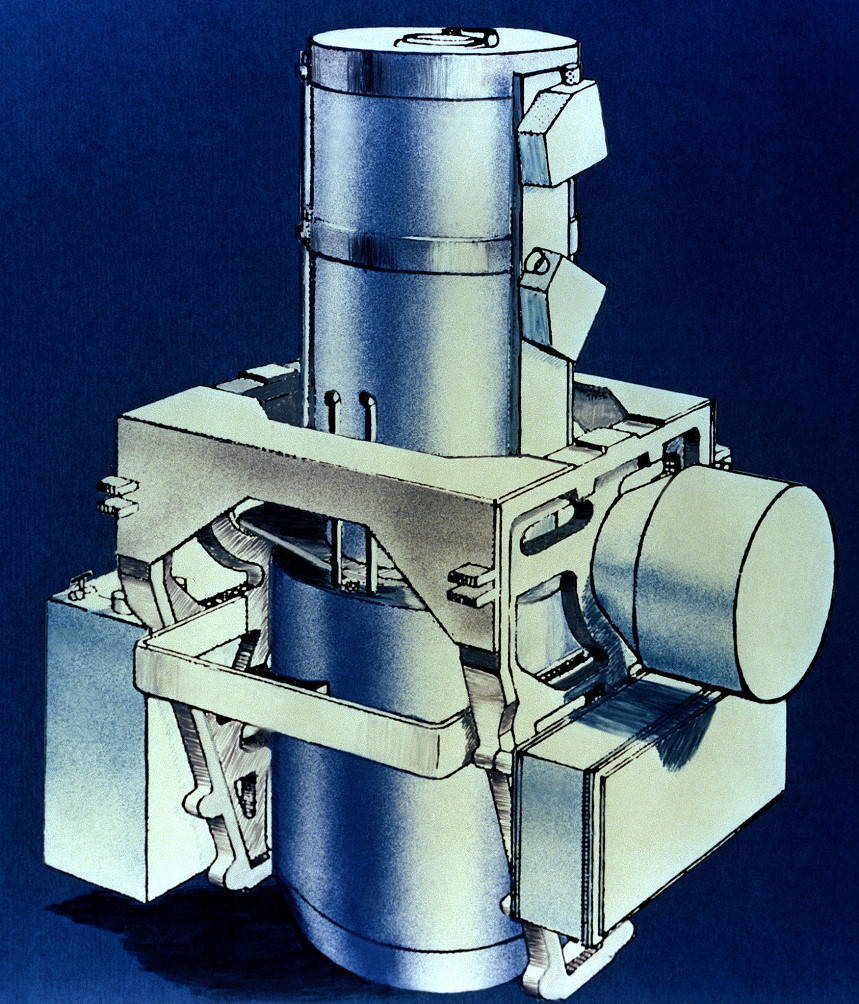

In the OPF, engineers removed about 1,000 thermal protection system tiles from Columbia. They densified and replaced about 800 of them and replaced the remaining 200 with brand new tiles. Workers removed, repaired, and replaced the orbiter’s toilet that encountered problems during STS-3. Ground crews installed some of the payloads, such as the Induced Environment Contamination Monitor (IECM) into the cargo bay and the Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System (CFES) into the middeck. Astronauts Mattingly and Hartsfield participated in a Crew Equipment Interface Test on May 9 to familiarize themselves with the location and use of experiments and equipment carried onboard the STS-4 mission. After a record-setting 42 days in the OPF, 11 fewer days than the processing time for STS-3, workers closed Columbia’s payload bay doors and towed it to the nearby VAB. There, ground crews lifted the orbiter and mated it to the ET and SRBs, completing the activity on May 20. A Shuttle Interface Test on May 21-25 verified the mechanical, fluid, and electrical connections between the orbiter, ET and SRBs, and the functioning of onboard systems. Columbia’s primary payload, the Cryogenic Infrared Radiance Instrumentation for Shuttle (CIRRIS), sponsored by the Department of Defense (DOD), arrived at Launch Pad 39A’s Payload Changeout Room (PCR) on May 22, marking the first use of that capability. Workers installed CIRRIS into Columbia’s cargo bay at the pad on June 5.

Left: STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly, left, and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield

train on the use of the Remote Manipulator System in the manipulator development

facility at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Right: Hartsfield, left, and

Mattingly receive training on the Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System

from McDonnell Douglas engineer Charles D. Walker, right.

On Feb. 22, 1982, NASA officially announced Mattingly and Hartsfield as the STS-4 crew, and for the first time, did not assign a backup crew. Managers believed they had a pool of trained astronauts to rely on in case they had to replace one of the crew members. Indeed, Mattingly and Hartsfield had served as the backup crew for STS-3 and had completed much of the shuttle operations training.

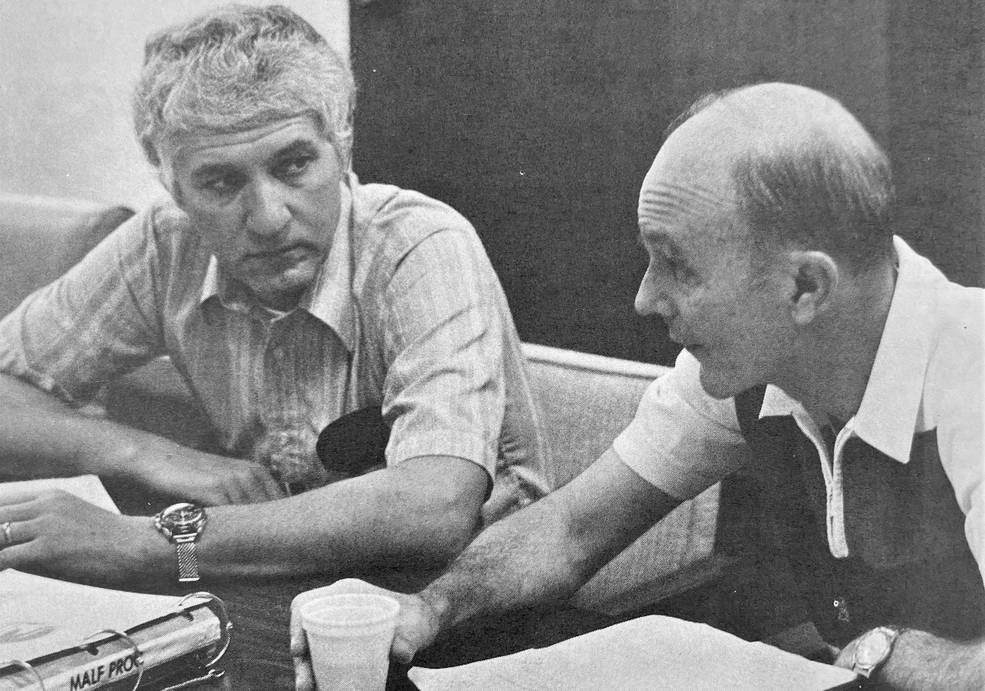

Left: STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly, left, and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield in the Shuttle Mission Simulator at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Right: Hartsfield, left, and Mattingly review procedures for their upcoming mission.

Left: STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly, left, and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield

during the preflight press conference at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Right: Hartsfield, left, and Mattingly flank student Amy Kusski, one of the two winners of the Space Shuttle Student Involvement Project selected for flight on STS-4.

On May 21, Mattingly and Hartsfield held a press conference in the JSC auditorium. Speaking about their upcoming seven-day mission, the final test flight of the program, Mattingly stated, “What we’re building here is a bridge to the future.” Hartsfield added, “We’re trying to prepare ourselves to move into the [operations] era,” referring to future space shuttle missions that would launch satellites and carry out extensive research. He noted that times for processing the shuttle at KSC have progressively decreased with each flight, underscoring the goal of transitioning to regular flight operations.

Left: Illustration of the Cryogenic Infrared Radiance Instrumentation for Shuttle, the primary Department of Defense payload on STS-4. Middle: The Induced Environment Contamination Monitor as seen in the payload bay prior to STS-3. Right: The Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System installed in Columbia’s middeck prior to launch.

Operational testing of the orbiter and payload activities determined much of the mission’s flight plan. Evaluation of the vehicle’s thermal performance in different attitudes continued the work begun on STS-3. The CIRRIS experiment, a testbed for future DOD operations on the space shuttle, planned to observe the Earth’s limb and atmospheric background. The astronauts planned to use the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) or robotic arm, to grapple and maneuver the IECM, flown previously on STS-2 and STS-3 but not removed from its position in the cargo bay. The 850-pound experiment set a record for the heaviest payload maneuvered by the RMS up to that time. The CFES, a payload developed jointly by McDonnell Douglas Astronautics and the Ortho Pharmaceuticals division of Johnson & Johnson, sought to use the special properties of microgravity to isolate ultrapure samples of biological materials. Mattingly and Hartsfield planned to participate in two biomedical experiments selected through the Space Shuttle Student Involvement Project for secondary schools.

Left: Space shuttle Columbia rolls out of the Vehicle Assembly Building on its way to Launch Pad 39A. Middle: Space shuttle Columbia during the rollout to the pad. Right: Space shuttle Columbia after its arrival at Launch Pad 39A.

On the morning of May 26, after spending just seven days in the VAB – a record at the time – space shuttle Columbia, mated to its ET and SRBs and mounted on MLP-1, began its slow journey to Launch Pad 39A. The 3.5-mile trip on the crawler transporter took about six hours. At the pad, engineers began preparing the vehicle for its next major activity, the Countdown Demonstration Test (CDDT).

Left: STS-4 astronauts Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly, front, and Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield leave the Operations and Checkout Building to board the transfer van to Launch Pad 39A for the Countdown Demonstration Test (CDDT). Right: Following the CDDT, Hartsfield, left, and Mattingly pose for photographers at Pad 39A as they answer reporters’ questions.

On May 29, Mattingly and Hartsfield participated in the CDDT, essentially a dress rehearsal of launch day but with no fuel loaded into the ET. They donned their pressure suits in KSC’s Operations and Checkout Building and rode the transfer van to Launch Pad 39A, where they climbed aboard Columbia. A computer problem delayed the test by more than four hours but concluded successfully just prior to simulated main engine ignition. On June 2, ground crews carried out a cryogenic fuel loading test by filling the ET with super-cold liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. Meanwhile, on June 1 at JSC’s Mission Control Center, controllers led by Lead Flight Director Charles R. “Chuck” Lewis, began a 57-hour simulation of STS-4, with Mattingly and Hartsfield participating from the shuttle mission simulator in Building 5. At KSC, the countdown preparation cycle began on June 15 and the final countdown on June 23, for the planned launch on June 27.

To be continued…

World events in May 1982:

May 1 – World’s Fair in Knoxville, Tennessee, opens.

May 2 – The Weather Channel airs on cable television as the first 24-hour all-weather network.

May 7 – IBM releases PC-DOS version 1.1.

May 13 – Soviet Union launches Soyuz T5 with Anatoli N. Berezovoy and Valentin I. Lebedev on a record-breaking 211-day mission to Salyut 7.

May 30 – Spain joins NATO as its 16th member.