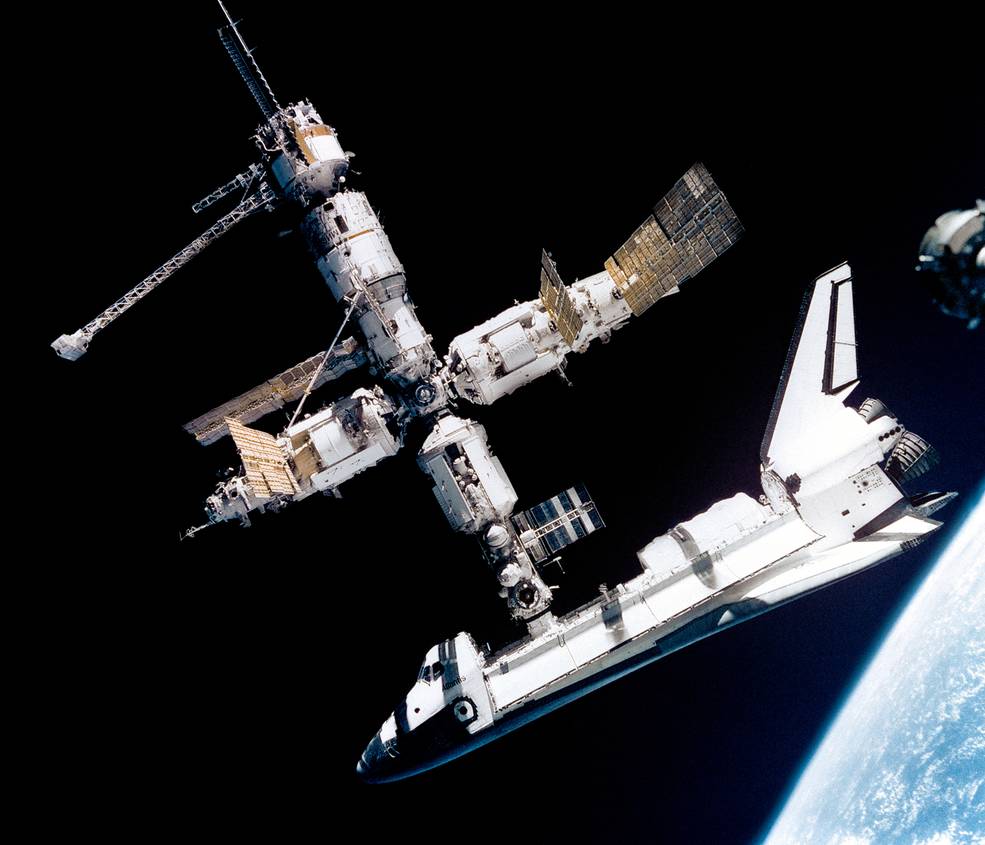

On March 23, 2001, after 15 years in orbit, Russia’s space station Mir reentered over the Pacific Ocean following a controlled deorbit maneuver. Despite highly publicized incidents late in its orbital life, Mir secured its place in history as the first modular space station that enabled semi-permanent human habitation in low-Earth orbit. The destination for a generation of Russian cosmonauts, Mir, provided opportunities for astronauts from other countries and space agencies to conduct research for their national programs on a commercial basis. The Shuttle-Mir Program saw nine space shuttle missions dock with Mir, and seven American astronauts join their Russian colleagues on long-duration expeditions as the two nations learned to work together in preparation for building and operating the International Space Station (ISS).

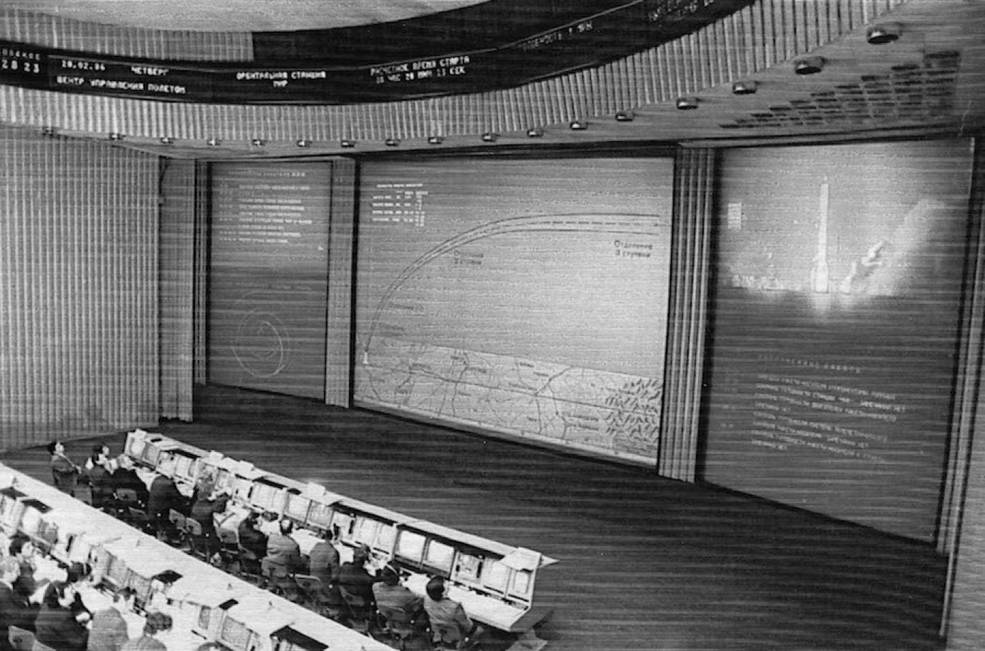

Left: In the Soviet mission control center, known by the Russian acronym TsUP, in Kaliningrad, now Korolev, outside of Moscow, controllers monitor the countdown for the launch of Mir’s base block module on Feb. 19, 1986. Right: The launch of Mir’s base block module at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Soviet Kazakhstan.

The Soviet Union approved the Mir space station program in 1976, its modular elements based on hardware and technologies developed during the Salyut and Almaz space station programs of the 1970s. The most significant improvement involved adding a docking hub at the core module’s forward end that could accommodate the addition of four large research modules. On Feb. 19, 1986, the Soviet Union launched Mir’s first element, called the base block or core module, enabling crews to live aboard. Over the next several years, the Soviets added five research modules, including two partially outfitted with science equipment provided by the United States as part of the Shuttle-Mir Program, to expand its capabilities and habitable volume. The overall mass of the complex increased from 45,000 pounds to 285,900 pounds, and its habitable volume from 3,200 cubic feet to 12,400 cubic feet, at the time the largest spacecraft in orbit.

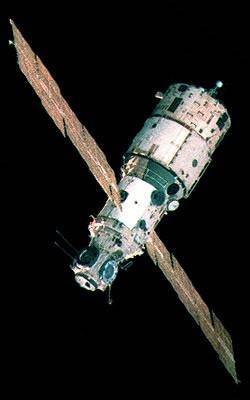

Left: The Mir’s base block module as seen by the first expedition crew in March 1986.

Middle: Space shuttle Atlantis docked with Mir in July 1995.

Right: Mir photographed by the STS-91 crew in June 1998.

During its 13 years of human occupancy, Mir hosted 104 cosmonauts and astronauts from 13 countries and space agencies. The first crew to occupy Mir, Leonid D. Kizim and Vladimir A. Solovev, launched on March 13, 1986. During their 125-day mission, they not only began commissioning the new station but also spent 50 days at the older Salyut-7 space station, conducting experiments and bringing 880 pounds of equipment, including a guitar, back to Mir. By the time Sergei V. Zalyotin and Aleksandr Y. Kaleri, the 28th and final main expedition crew, departed the station on June 16, 2000, Mir accumulated an impressive series of accomplishments. Among these were the three longest space missions to date, extending the spaceflight record first to 326 days, then to 366 days, and finally to 438 days, a record that stands to this day. Mir hosted nine international astronauts as part of long-duration missions, including seven Americans as part of the Shuttle-Mir program and numerous short-term visitors, including the crews of nine space shuttle missions. Of the Mir visitors, 42 went on to fly on the ISS, bringing their previous experience to bear on the assembly and operations of the new facility.

Left: Mir’s first resident crew, Leonid D. Kizim, left, and Vladimir A. Solovyov, prepare to board their

spacecraft at the launch pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Soviet Kazakhstan. Middle: Mir expedition

18 Commander Vladimir N. Dezhurov, left, and STS-71 Commander Robert L. “Hoot” Gibson shake hands

during the first Shuttle-Mir Program docking. Right: Mir’s final resident crew, Sergei V. Zalyotin,

left, and Aleksandr Y. Kaleri following their landing in Kazakhstan.

Mir’s controlled deorbit and reentry followed a carefully planned stepwise approach. On Oct. 19, 2000, Progress M43 arrived at Mir and used its engines to boost the station to a higher orbit, allowing for a controlled deorbit early the following year. Progress M1-5 arrived on Jan. 27, 2001, carrying 5,900 pounds of propellant for the deorbit burns. Through February, Mir lost orbital altitude at a somewhat unpredictable rate of 200 to 650 meters per day, the uncertainty caused by variability in solar heating of the Earth’s upper atmosphere. On Feb. 19, the space station celebrated 15 years of in-orbit operations. By March 1, its altitude had dropped to 164 miles, and the rate of descent increased to one mile per day. In the early morning hours, Moscow time, of March 23, Progress M1-5 fired its eight docking and attitude control thrusters, generating a total thrust of 220 pounds, for nearly 22 minutes. This changed Mir’s orbital altitude to 136 by 117 miles. One orbit later, a second burn lasting 24 minutes dropped the low point of Mir’s orbit to 98 miles. Mir then completed two more orbits around the Earth before the final burn using the Progress’ thrusters and its main rendezvous engine for a total of 660 pounds of thrust. Controllers allowed the engines to burn to fuel depletion as Mir passed out of radio contact with the ground. Mir entered the Earth’s atmosphere at an altitude of about 62 miles and began to disintegrate at about 50 miles. Debris impacted the south Pacific east of New Zealand. Among those present to observe Mir’s reentry from the island nation of Fiji were Mir designer Leonid A. Gorshkov and cosmonauts Sergei V. Avdeyev, Yelena Y. Kondakova, Musa K. Manarov, and Vladimir G. Titov, all of whom spent at least six months aboard Mir.

Left: In Fiji to observe Mir’s reentry, cosmonauts Yelena Y. Kondakova, Musa K. Manarov, Vladimir G. Titov, Mir designer Leonid A. Gorshkov, and cosmonaut Sergei V. Avdeyev. Right: Debris of Mir streaking through the sky as seen from Fiji as it reentered the Earth’s atmosphere.

Also, monitoring and controlling Mir’s deorbit and reentry were the operators in the Russian flight control center (TsUP is the Russian acronym) located in the Moscow suburb of Korolev. Their professionalism in carrying out the task must have been mixed with strong emotions as they watched the end of the space station on which many had devoted their entire careers, working in the TsUP for all of the base block’s 86,331 orbits around the Earth as it traveled 2.2 billion miles. The workers took solace that the ISS was in its earliest stages of assembly, and many of the lessons learned from Mir, including how to deorbit such a large spacecraft, would be passed on to the new program.

Left: One of the final images returned from Mir, from a television downlink from the Progress

M1-5 vehicle, as seen in the Russian flight control center (TsUP is the Russian acronym)

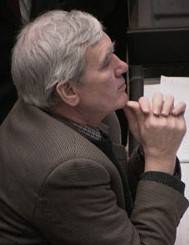

in Korolev outside of Moscow. Middle: Flight Director Viktor D. Blagov in the TsUP during

Mir’s reentry. Right: Map projection in the TsUP depicting Mir’s final orbit.

Image credits: Russian Space Web.