Tenacity and drive are hallmarks of Cornell University’s Cislunar Explorers Team. But there is another key factor in building and testing their spacecraft: Just add water.

“The core concept behind our work is using water as rocket fuel,” said project manager Kyle Patrick Doyle. “It’s something that we’ve been looking at for a long time, and it’s exciting to have a chance to test our technology in space,”

The team’s CubeSat propulsion idea focuses on a water-electrolysis propulsion system. By zapping H2O with electricity, the bond between hydrogen and oxygen can be overcome, decomposing the liquid into a gaseous mixture that readily combusts.

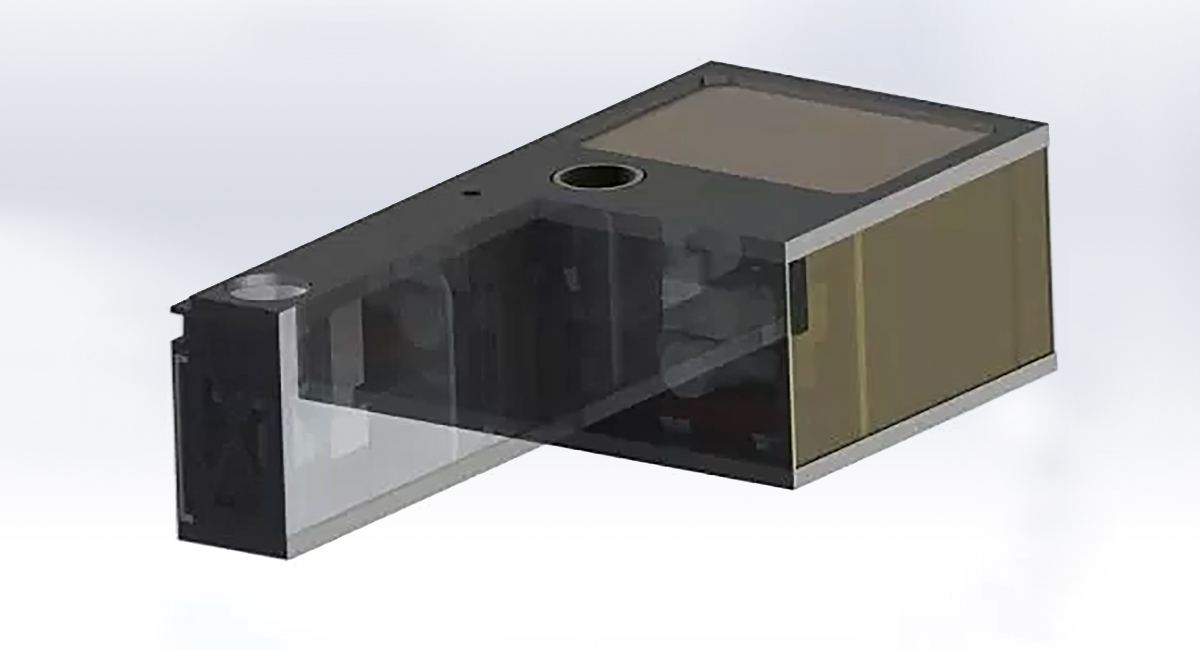

Briefcase-sized Spacecraft

Cislunar Explorers’ concept consists of a pair of spacecraft on a mission to orbit the moon. These two spacecraft are mated together as a “6U”-sized box – small enough to fit in a briefcase, explains Doyle. After deployment from the launch vehicle, they will split apart and each give their initial rotation in the process of decoupling.

The novel propulsion system using inert water will be tapped to enable the Cislunar Explorers to carry out a gravity assist with the moon, and then be captured into lunar orbit. Spacecraft maneuvers will be directed by a ground station at Cornell.

“Doing this with a CubeSat is a challenge,” Doyle said, “to attain reasonably precise maneuvers and then hit your gravity assist targets with this platform.” Cornell researchers have been working on the idea of a CubeSat using electrolysis propulsion in low-Earth orbit for several years, he said, “but the opportunity to go to the moon doesn’t come around very often.”

Democratizing Access to Space

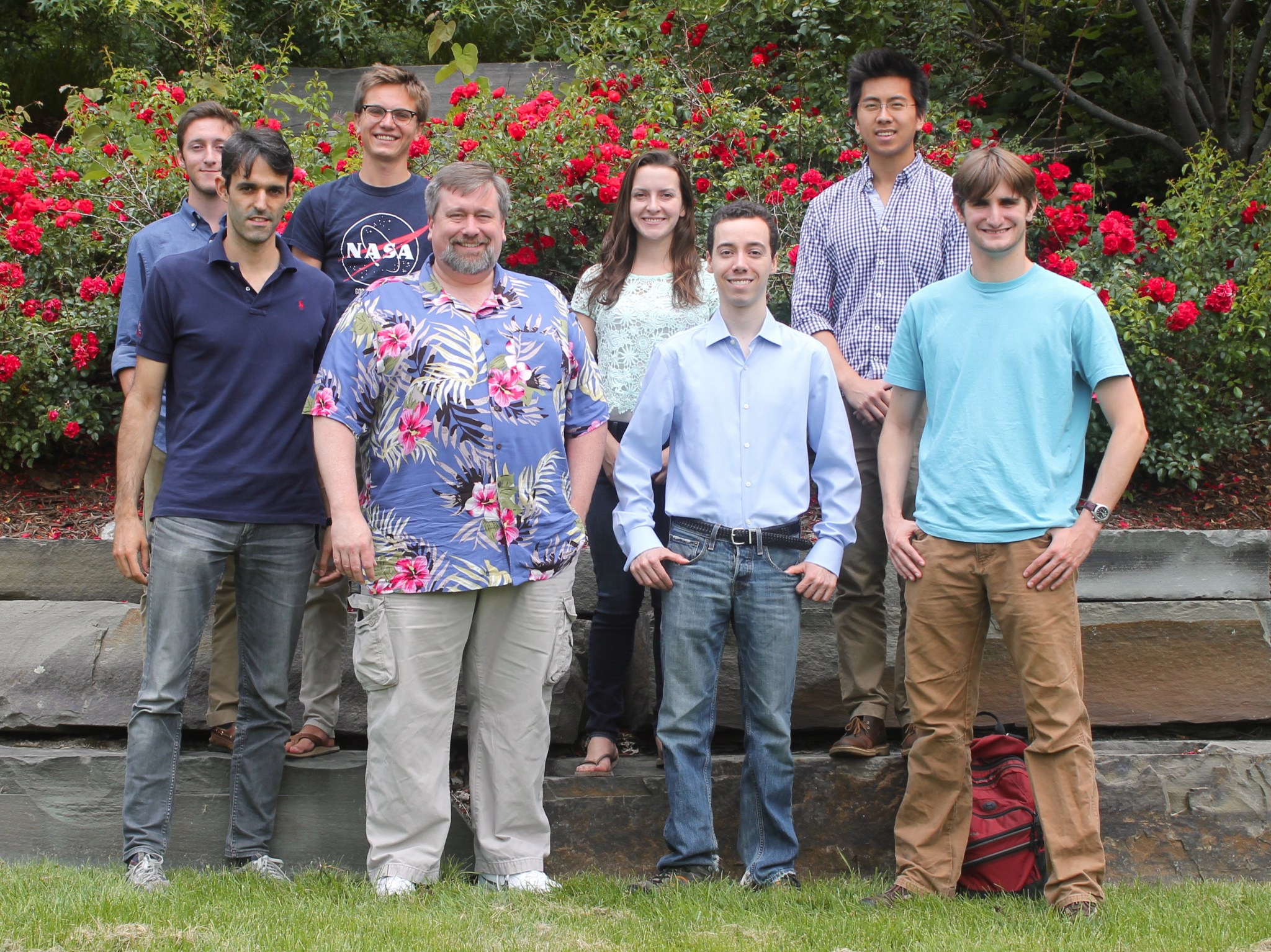

“We see this challenge as an opportunity to democratize access to space,” said Mason Peck, associate professor at Cornell and the principal investigator for Cislunar Explorers.

“First of all, it’s exciting for all of us to participate in lunar exploration, even to a small degree. But more than that, this project may enable many others to follow in our footsteps,” he said.

Peck said that the Cornell team is making all of their hardware and software designs available online. Doing so allows other universities and research organizations to build their own versions of their Cube Quest entry.

“In the longer term, if this water-based propulsion technique is successful, we hope it will kick start the use of in-situ resources for refueling spacecraft for commercial purposes or science,” Peck said.

Technical Issues

Doyle underscores the technical issues surrounding water-electrolysis propulsion.

“It’s an unusual application. The piping between propellant tank and combustion chamber has been fairly challenging. It requires a valve that opens easily one way, and then can withstand the small propulsive detonations,” he said. “And we think we have it.”

Testing of Cislunar Explorers’ hardware is largely being done on campus, including spacecraft electronic circuitry “to make sure they all play nice with each other,” Doyle said. Similarly, a phase two safety review is being closed out.

“I’m having the time of my life. This is a great project. I have learned so much, particularly how iterative systems engineering and design really is. You read in books how making a change here will propagate through other things,” Doyle said. “But it’s something else to experience it.”

Minor tweaks in one area can cascade through the whole project, he said. “Making a change to solve a problem while causing the least disruption to the rest of the project – that’s been a valuable lesson for me.”

Pathfinder for the Future

Turning his eye on the future, Doyle said he sees their Cube Quest spacecraft as a pathfinder. The water-electrolysis propulsion system for Cislunar Explorers can’t refuel itself.

“But by demonstrating that water is a viable propellant,” he said, “having a future lander touch down on one of the icy moons in the solar system, you can gather up the ice, refuel your spacecraft and send that spacecraft to further places,” he said, “and that’s a really exciting prospect for our technology in the future.”

More about Cube Quest

The Cube Quest competition offers a total of $5 million to teams that meet the challenge objectives of designing, building and delivering flight-qualified, small satellites capable of advanced operations near and beyond the moon. The competition is sponsored by NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate and managed by the Centennial Challenges Program at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama,

For more information about the Cube Quest Challenge, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/cubequest

For more information about Centennial Challenges, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/spacetech/centennial_challenges/index.html

To learn more about the Cislunar Explorers Team, visit:

https://cislunarexplorers.wordpress.com/cubequest-challenge/