When their spaceship was severely damaged 200,000 miles from Earth – 45 years ago this week, it was like a bad dream from which the Apollo 13 crew could not wake.

Moments after they finished a TV broadcast late on April 13, 1970, a spark ignited one of the oxygen tanks on the Apollo 13 spacecraft. The resulting explosion plunged an entire nation into an anxious three-and-a-half day drama.

The blast obliterated one of three fuel cells and an oxygen tank. Oxygen jetted into space from the command module’s remaining tank.

“Houston, we’ve had a problem here,” astronaut Jack Swigert told mission control in Houston at what was then NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center (now Johnson Space Center).

“We’ve had a main B bus undervolt,” Mission Commander James Lovell said. One of the command module’s two main electrical circuits had experienced a drop in power.

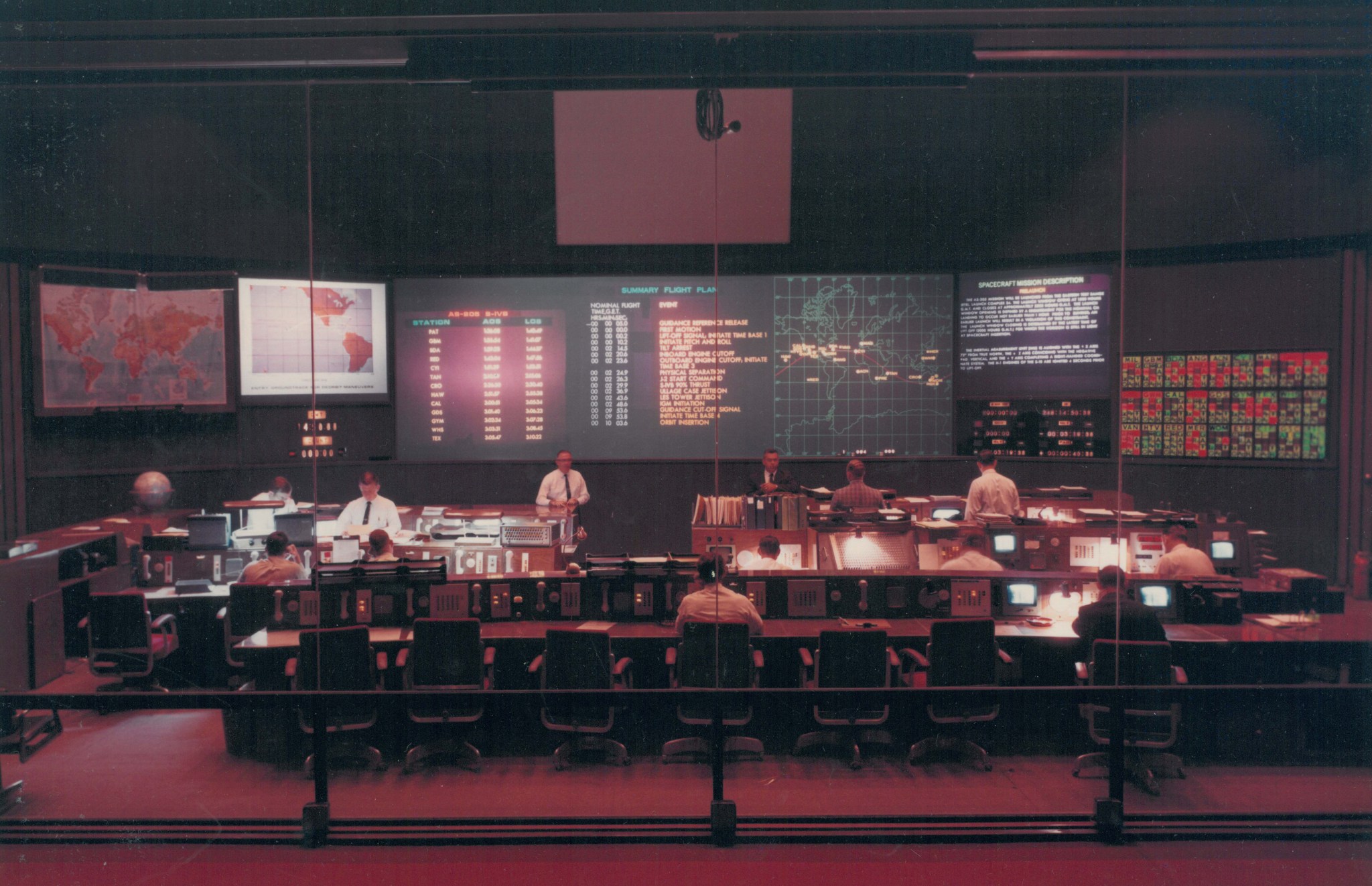

The Manned Space Flight Network at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, made Swigert and Lovell’s reports possible. The network’s tracking stations linked the spacecraft to Earth, where its signals were transmitted through Goddard. Nearly three million circuit miles of communication channels in the NASA Communication Network conveyed the messages received at Goddard to the Mission Control Center in Houston.

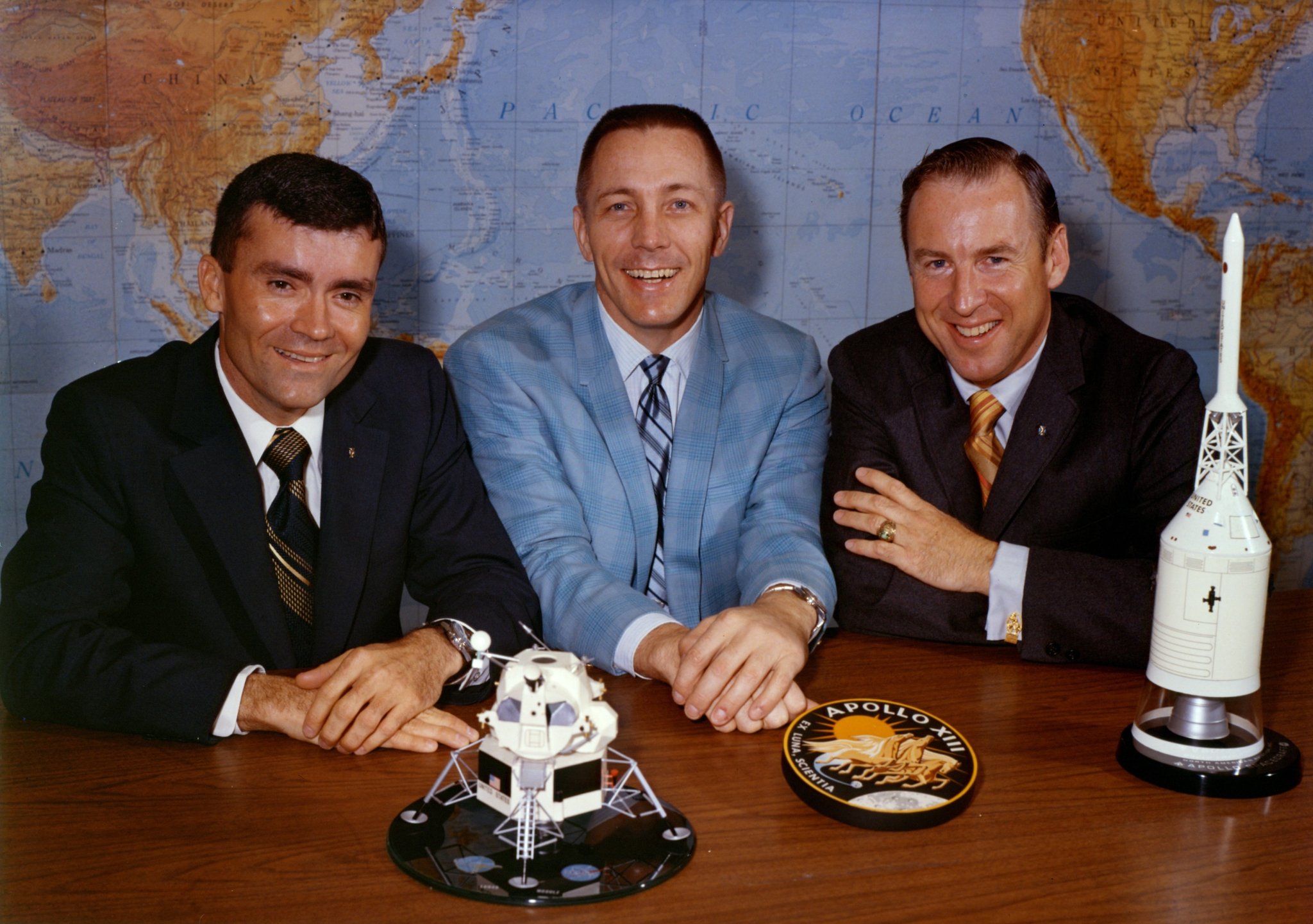

Less than two hours after Swigert’s message was transmitted to Houston, mission control pronounced the command module mortally wounded. With only 15 minutes of power left, astronauts Swigert, Jim Lovell and Fred Haise escaped to the “life boat” of the lunar module.

President Richard Nixon learned of the crisis shortly after the explosion, and he met with Goddard Center Director John F. Clark the following day for an update. William C. Schneider, director of NASA’s Skylab program, briefed the president on the status of the rescue mission in Goddard’s Manned Space Flight Network control room, through which communications to and from Apollo 13 passed.

The nation watched for the latest updates from their television sets, transfixed, as the rescue mission unfolded.

The crew spent three-and-a-half grueling days in the lunar module. They rationed food and water, which mission designers had only intended to last two men a day and a half, not three men three days. Carbon dioxide reached dangerous levels in the lunar module before the team managed to convert square filters from the command module to fit in the round openings on the lunar module. When the crew shut the instruments off to conserve power, the inside temperature reached an icy 38°F.

But reorienting the lunar module to a return-to-Earth trajectory from a lunar landing course proved to be one of the most difficult and important obstacles to hurdle.

Navigation and targeting functions were unavailable. Debris from the explosion made it impossible for the crew to navigate by the stars using the on-board sextant. In a nail-biting maneuver, the astronauts improvised by using the limb of Earth, or the horizon where Earth meets the atmosphere, as a reference point. They were then able to perform a controlled fuel burn to shorten the time ’til splashdown on Earth.

Flight Director Gerald Griffin in Houston later recalled of the alignment maneuver, “Some years later I went back to the log and looked up that mission. My writing was almost illegible, I was so damned nervous. And I remember the exhilaration running through me: My God, that’s the last hurdle – if we can do that, I know we can make it. It was funny because only the people involved knew how important it was to have that platform properly aligned.”

On April 17, 1970, the crew splashed down in the Pacific Ocean near Samoa.

The performance of Goddard’s Manned Space Flight Network contributed significantly to the safe return of the astronauts, said Dale Call, then-MSFN network director. He said the network performed better then than on any previous Apollo mission.

Houston’s flight operations director commended MSFN operators for their critical help with the mission.

Throughout the crisis, the network remained consistent and reliable in relaying communications to and from Apollo 13 despite the tracking difficulties imposed by the failure of the command module. As engineers on the ground hurriedly created workarounds for each challenge that arose, such as the carbon dioxide issue, they could only be communicated to the crew via the network.

Although the mission was not able to achieve its scientific goals, NASA’s rescue mission was an agency triumph.

“With astronauts Lovell, Haise and Swigert safely back on Earth, a surpassing human drama that gripped the world for three-and-a-half days at last has a happy ending,” President Richard Nixon said following the astronauts’ return. “Their safe return is a tribute to their own courage and also to the ingenuity and resourcefulness of those on the ground who helped transform potential tragedy into a heart-stopping rescue.”

Ashley Morrow

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland

Originally Published April 14, 2015